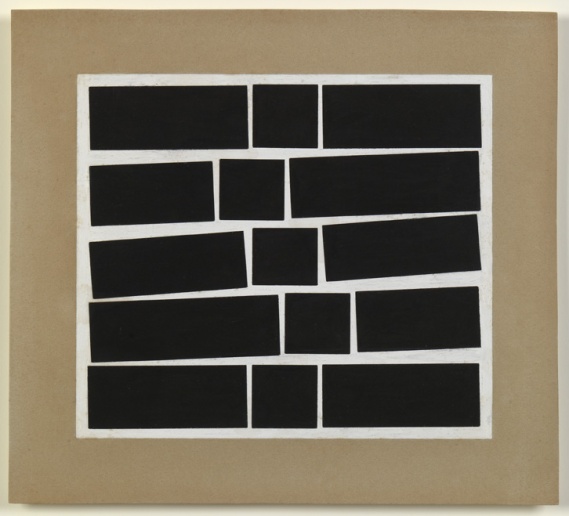

Kazimir Malevich, ‘Black Quadrilateral’, c.1915. Greek State Museum of Contemporary Art – Costakis Collection, Thessaloniki

Adventures of the Black Square, Abstract Art and Society 1915–2015, at the Whitechapel Gallery, London

It was only a few months ago that Malevich’s monochromes were last in London, venerating his radical contribution to the end of pictorial painting and some proclaimed, to the end of art itself. Tate Modern’s Malevich, Revolutionary of Russian Art (16 July – 26 October 2014) was very much a historical survey; looking back at the long shadow Malevich’s Black Square – a headstone for representational painting – cast over the history of modern art. Adventures of the Black Square, Abstract Art and Society 1915–2015 at Whitechapel Gallery until 6 April clearly and alternatively positions the work’s reductive form (in this exhibition it is Malevich’s diminutive undated Black Quadrilateral that is featured) as the beginning of a new art starting in Russia and Northern Europe in the early twentieth century. The spread of geometric abstraction is then documented chronologically as it travels internationally throughout the next hundred years. Rather than Black Square being revered as merely a portrait of an idea, it is shown as the initiator of geometric works that connect with, reflect or challenge society. Adventures of the Black Square presents abstraction as not being estranged from social reality, that its concern with form, shape and colour throughout its history are intrinsically linked to politics and expressions of modern living.

The exhibition is vast and frenetic, featuring work by over 90 artists, presented under four different themes: Utopia, Architectonics, Communication and The Everyday. It feels very much like a show of two distinct halves. The first gallery is a comprehensive survey of geometric abstraction in the 60 years after Black Square was first seen in the Last Futurist Exhibition of Paintings 0.10 in 1915. One small but possibly pedantic gripe is that Malevich’s Black Quadrilateral opens the show with little historical context, with no direct reference to the influence of cubism or futurism; it’s as if the painting was conceived in an art historical vacuum. What immediately follows the now fragile looking Black Quadrilateral in the exhibition is a substantial selection of Suprematist works that radiate a sense of escape from the conventions of figuration and exude the possibility of revolution. Often suggesting a diagrammatic use of shape and form, the earliest pieces in the exhibition go the furthest in suggesting how geometric abstraction was used to ‘work out’ a visual language and the lived experience of a new world; El Lissitzky’s elegant portfolio of six lithographs 1o Kestnermappe Proun (1923) and Iakov Chernikov’s drawings of fantasy architectural structures (1929-33) are notable highlights for me, although there is a lot of excellent material in the initial room of the exhibition.

The presentation of the work from the first three decades of the 20th century is especially dynamic, with a huge volume of work arranged with the energy of an explosion. This part of the exhibition has a distinct, political narrative that explores the inventiveness of ideas and radical thought. From that point on the exhibition demonstrates, somewhat less comprehensively, the journey of geometric abstraction through time and across continents, and how it has filtered from drawing, painting and sculpture into the wider world, in magazines, textile design, architecture and film. Latin America is well represented, the work of Hélio Oiticica, Lygia Clark and Lygia Pape demonstrating the neo-concrete adaptation of geometric shapes into organic three-dimensional objects to be manipulated by participants and to be experienced sensorially to counteract the urban alienation created by a modern society. British artists are scarcer, perhaps reinforcing Britain’s historical tendency to overlook work with a rational aesthetic. Jeffrey Steele’s dynamic Third Syntagmatic (“Tsunami”) (Sg VIII I) (1965) cuts a lonely figure as the only representative work of the Systems Group. There are some obvious omissions from British geometric abstraction: Bridget Riley, Mary and Kenneth Martin, Victor Pasmore, Marlow Moss to name but a few. Artists from the Middle East are represented only by the collages of Iranian Nazgol Ansarinia, surprising considering Islam’s long history of producing geometric work. Despite my personal criticism of what was missing from the exhibition, the first gallery does tell an ambitious and interesting story of the development of geometric abstraction and its alignment with a quest for social or political change. The first part of the room is outstanding in quality and breadth of material, the second half looser in narrative connections between counties and philosophies but still presents a strong grouping of work.The second half of the exhibition, in two upstairs galleries at Whitechapel, abruptly shifts from a survey of historical significance into a pot pourri of geometry as borrowed language and at worst, pastiche. The selected work is distinctly different from the first gallery; made by individual contemporary artists (rather than groups with a shared interest or vision) who have used geometry as a surrogate for a subtext rather than visual matter in its own right. This does not necessarily mean that the work is bad or ineffectual, but I do question its place in the exhibition and the overall hypothesis of the curation. Gunilla Klingberg’s Spar Loop (2000) is a good example of geometry used as token, rather than as content. Spar Loop is a hypnotic animation of shifting geometric shapes and bold colour; while watching it becomes evident that the animated forms are made from the red, white and green logo of the convenience store ‘Spar’. It may present a connection between geometry and social comment, but I don’t think it is geometric abstraction, or in a meaningful dialogue with its history. In a similar vein, Keith Coventry’s 1995 Sceaux Gardens Estate (1995) is a parody of modernist formalities, an arrangement of cheerless yellow rectangles on a dirty white ground, its form directly borrowed from the plan of a London housing estate. There are links to architecture’s utopian ideal for social housing, but I find it difficult to see beyond the literal connotations of the painting. Using an abstract language is not the same as working in the traditions of abstraction.

Malevich’s radical monochrome is particularly well referenced in the later works, the ubiquitous Black Square appears literally in, among other works, Rosemarie Trockel’s knitted composition Cogito, ergo sum (1999) and in Angela de la Cruz’s Shrunk (2000). The latter is a deconstructed black monochrome painting, folded on the diagonal and slumped apologetically in the day-glo reflection of Peter Halley’s jazzy Auto Zone (1992). These works rely on the Black Square as idea, but in doing so surely miss the point by representing a direct homage, a gesture largely absent in the work in the first gallery. Adventures of the Black Square does a good job of showing how abstraction grew from a radical ideology that suggested a new democracy of art, but falls rather short of demonstrating how it is continuing to be developed today. Sadly, David Batchelor’s puerile October Colouring-In Book (2012-13) presents an almost convincing argument that it might not be.

Reflecting on Adventures of the Black Square has left me with some conclusions about the exhibition – overwhelmingly that the first half is very good, but the second half less so – and also a few unresolved thoughts. There have been several major recent exhibitions of geometric abstraction: Tate’s Malevich, Revolutionary of Russian Art, Mondrian and his Studios and the excellent Nasreen Mohamedi; Radical Geometry at Royal Academy of the Arts; and Gego. Line as Object at Henry Moore Institute, amongst others. Why is geometric abstraction suddenly popular in Britain; is it a trend based on aesthetic style that will pass, or a serious reinvestigation of a previously overlooked way of working? Are we looking back nostalgically to more radical times and/or hoping that art can still change the world? Is there a younger generation of artists using geometry that embody the same spirit of Modernism as can be seen in the first part of Adventures of the Black Square, or has that time ended, making way for a different perspective on geometric abstraction? 100 years after Malevich declared, ‘We Suprematists, throw open the way to you. Hurry! – for tomorrow you will not recognise us’, is it all over, or is there still more to come?

Adventures of the Black Square, Abstract Art and Society 1915–2015, is at the Whitechapel Gallery until 6th April 2015.

![El Lissitzky, '1o Kestnermappe Proun [Proun. 1st Kestner Portfolio]', Published 1923](https://abcrit.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/el-lissitzky-1o-kestnermappe-proun-proun-1st-kestner-portfolio-published-1923.jpg?w=439&h=601)

Excellent Review thank you

LikeLike

Thanks Charley, great review, I am really looking forward to seeing the show for myself. I am interested in your comment on David Batchelor, and I must take issue with you on his October Colouring-in Book. Playfulness and irreverence may well be boyish traits but I don’t think the work is puerile. Neither do I think it anywhere near casts doubt on the future of abstract painting. Surely, Batchelor’s move in this work, criticising as it does the postmodern tendency to favour text over image, especially coming from someone who is no stranger to text, has some resonance with Malevich’s project. If “Adventures of the Black Square presents abstraction as not being estranged from social reality” but “intrinsically linked to politics and expressions of modern living” Batchelor seems to me to be bang on target, reasserting the primacy of coloured-in geometric shape over art theoretical text and celebrating the colour of the city rather than what has come to be known as colour theory, preferring to theorise about the part that colour plays in the modern world, and criticise our suspiciousness towards it. I think his criticism is given form in the October Colouring-in Book, choosing also to be critical of Malevich’s transcendence or, less heroically, suppression, of colour, whilst also continuing in his footsteps. So, for me, Batchelor’s work could indeed be a demonstration of how abstraction is continuing to be developed into the future.

LikeLike

Hi Andy, I have to say I completely and utterly agree with Charley’s description of this piece. It is so limp, and so, so, so obvious. It’s a shame that given the limited space, and the fact he has a whole room to himself elsewhere in the Whitechapel, that the curators felt to need to give Batchelor a whole wall for such a thin idea.

LikeLike

Thanks for your comments Andy. I don’t want to spend too long writing about David Batchelor, but rest assured that I don’t really think his October Colouring-In Book casts doubt on the future of abstract painting; that was written with my tongue firmly wedged in my cheek. I actually don’t think Batchelor’s felt tip doodling has anywhere near enough charm or substance to threaten the future of anything, and I hope that your proposition that this is how abstraction could be developed in the future proves to be false. I do appreciate your input to the discussion and you have, momentarily at least, made me reconsider Batchelor’s work based on your well-constructed evaluation of it. However, I still can’t agree. I prefer October left alone in black and white and I don’t see Batchelor as making any meaningful contribution to a contemporary consideration of abstract painting.

I’ll look forward to hearing your thoughts on the show when you’ve seen it in person, there is thankfully a lot more that is worth seeing than the colourings in of David Batchelor.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Dear Charley ,Thanks for an insightfull review of this show.Its great to have a new voice on Abcrit.As is often the case great historical precedence completely outweighs the Art of the present .The hip curators must weep at the weakness of their friends and colleaques attempts at what is at most merely pastiche.How is Peter Halley going to stand up to Malevich or Ian Davenport to Morris Louis when the content of their work is conspicuous consumerism ?The reason I was attracted to Abstraction in the first place was because it heralded revolution from established and stuffy norms .I have never lost the Romanticism that great Art can change Society and would agree with Picasso that Painting is dangerous.The fact that Painting is being made anywhere on the planet for authentic reasons of emotional and spiritual rejuvenance,of lanquage and understanding ,and and not merely for profit or fame, should be a cause for celebration.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks for your thoughts Patrick. It’s interesting that the work in the second half of the show that does seem driven by real political comment, such as ‘Retoque/Painting, Ex-US Panama Canal Zone’ by Francis Alÿs isn’t an abstract painting. The show is definitely lacking in this area. I wonder if this is where we are now with painting (and the curation of it), hence my question about style/trend and geometric abstraction’s recent popularity in the UK.

LikeLike

Wot, no Riley?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on patternsthatconnect and commented:

Great review by Charley Peters ending with with some great questions…

LikeLike

Thanks Andy!

LikeLiked by 1 person

A hundred years of abstract art to choose from, and this is it? I think it’s a poor show, badly hung, if that’s the right word; ‘cobbled’ might be better. The few pieces of work upstairs that may have been worth a look were pretty inaccessible to the eye. I know we are long past the point where curators are expected to themselves have an ‘eye’; and the art of curation is long past the point of being the selfless presentation of the work of the artist in the best possible light. Curation is now an intrusive collaboration or an unwanted intervention between the art and the viewer. This show is another large stride down that particular tunnel of oblivion, and also very badly labeled. We expect nothing more from Whitechapel. Actually, in a show that was something of an affliction, the labels provided a bit of light relief, coming as they did straight out of ‘Pseud’s Corner’. Upstairs especially had its lol moments, particularly when the attempt was made to link bits of grotty tat to profound social issues…

I can’t comment with any authority on the puerility or otherwise of David Batchelor’s work, since I have no recollection of looking at it. Must have blinked. What I do know is that most of what I did see in the show was trivial and/or boring. I include in that criticism Malevich’s black quadrilaterals (of any description); did he feel he was improving them as he made more? I also think the argument that this work somehow connects with utopian left-wing politics is naïve (yes, you, Patrick). There is absolutely no ‘intrinsic’ link in any of the work to politics – all such links are extrinsic – and what links there are to modern society in general are in every case to the detriment of the work. I mean by this that it is only the very close parallel between most of these paintings and sculptures and the graphics and design work of the time that forms the link, the latter making such a large contribution to what we understand as ‘modernism’. I’m no snob about this; I don’t think fine art is intrinsically better than applied art, and the opposite is often true (Anni Albers textiles are often better than her partner’s boring paintings). I quite like a degree of minimalism in design and architecture, but in art it’s facile. Such closeness to design, in geometry, pattern, repetition etc. is detrimental to painting and sculpture. Most of the works in this show are ‘designed’; downstairs there is an historical justification for testing out the precedents for this approach; upstairs it’s just a question of mimicked tropes and more and more conceptualism. Even the minimalist quiddity of Carl Andre’s floor piece is just another dumb grid design. It’s a short step from here to object-less conceptual art, which follows the same path, lacking in all visual content.

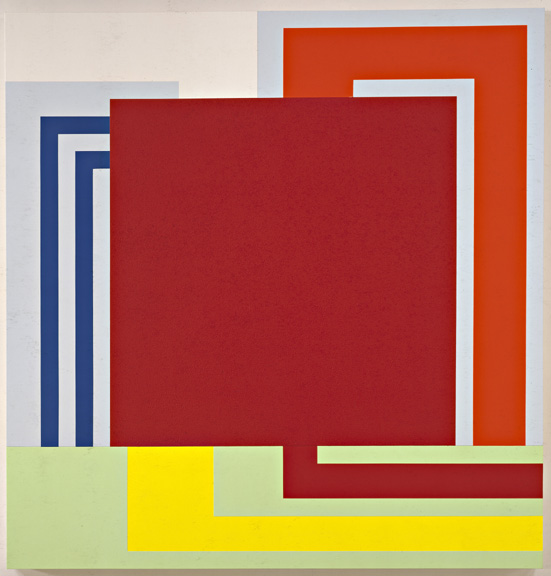

There are a few exceptions in the show. The stand-out painting, by a mile, is the Popova (illustrated), which is subtle, spatial and sophisticated and greater than the sum of its parts; a grown-up painting, in fact. It’s so much better than the Mondrian, which, with its unbearably nasty optical effects, is very unpleasant to look at (Alan Gouk did a brilliant job of analysing Mondrian’s failings here: http://abstractcritical.com/article/mondrian-nicholson-in-parallel-2/ ). All the big modern names here – Halley, Coventry, Batchelor, de la Cruz, Trockel – are conceptual designers. No doubt Andy will lap all this up in a trance-like state. To me, it’s just real boring, and says nothing for the future. You need to see this show so you can comment here, but for something good to look at, go see the Rubens afterwards.

LikeLike

I agree (more or less) about the curation, though I enjoyed the show, the first half at least despite it: I think it captured something of the excitement of abstract art’s beginnings, even if this frequently overwhelmed the individual works. It did occur to me that it – particularly as it went on – looked like it was organised by someone who has probably spent quite a lot of time looking at art in art-fairs.

I’m not sure that there is such a thing as an intrinsic link. Surely as soon as there is a link it has to be extrinsic? Of course none of this work passed any legislation or whatever, but it was bound-up with with political ideas and inspired by huge political changes.I think the exhibition figures this dynamism, even as it blurs the details.

LikeLike

PS. It made me regret (as I’ve done a few times) missing this show http://abstractcritical.com/article/dynamo-a-century-of-light-and-movement-in-art-1913-2013/, which I suspect puts the Whitechapel to shame. I’d be interested to know how Katrinna (or anyone who has seen both) thinks they compare.

LikeLike

PPS. I think there is a more interesting point about why the exhibition avoids the abstract painting & sculpture (chiefly related to Ab-Expressionism, but not exclusively) which tried to reconcile an abstract language with an art which could be measured, or at least visibly drew sustenance from, the grand tradition of Western painting – though it was probably only de Kooning who actually liked Rubens….

LikeLike

Here is a painting with an intrinsic link to politics: http://fineartamerica.com/featured/russian-revolution-1922-granger.html

If you are then going to say abstract art cannot have such a link, I’m inclined to agree.

LikeLike

You dont need a weatherman to know which way the wind blows.Its fascinating to me to watch Robin put his head firmly in the sand ,ostrich -style and deny that Abstract Art is Political.The decision to make Paintings and Sculpture without reference to illusion or mimesis seems to me to be absolutely radical.It questions the apparatus that the audience will use to experience it ,how it is enjoyed.We/ve been here before, but it challenges the observer to activate the work thru feeling.To be alive now ,feel,think ,live ,enjoy in the moment ,on your own on a number of levels..That is revolutionary and so far from the cynical assumptions and platitudes of Le Pen or Farage,who deal in utilising deep-seated fears about job-loss ,immigration and the romanies at the end of the lane.Events since JFKennedys assasination have so eclipsed left -wing politics that we are all now libertarians who seek a fairer functioning society.

LikeLike

I am with Andy here. I am sure David Batchelor is not totally dis’ing the October group but a moment of irritation prompted him to make this wisecrack. – and it does form a part of his well known explorations into the hierarchy of colour and form. The piece puts me in mind of DADA and absurdism which is surely the flip side to art ‘concrete’ – different sides of the same coin. Fascinatingly, Anthony Hill, who is one of the key figures of the British/European constructionists, not only bridged the gap between them and the later mathematically influenced systems group but also later had a dadaist alter-ego Achill Redo who produced slightly crazy ‘pictures’ and collages, and those who know him have enjoyed a life time of wit and satirical social commentary. My colleague Andrew Bick could elucidate here.

On this note – on contradictions or rather on ignorance – I am of course delighted to see Jeffrey Steele represented in the show; also in the slide show and the leaflet. I visit him often and we talk about art and politics. He has come to the conclusion, in concurrence with Robin, that particular paintings or works, artists in fact, cannot – even should not – be setting out to change minds with an overtly political message. He would argue that producing paintings and living the life of an artist is a (left-wing) political act in itself and more importantly art needs to be elevated and appreciated for itself. And that’s the bit that people find hard – always searching for some sort of narrative, justification: yes something extrinsic. As you will see from the label next to Jeffrey’s work in the show he was a total sceptic with regard to his predecessors’ notions about art and architecture merging and becoming one: life/art/environment. In reality the ‘This Is Tomorrow’ exhibition (pairing artists and architects) was apparently fraught with argument – and of course out in the real world those extra large brutalist tower blocks never worked out! No utopia there! So, perhaps there was also an absurdity about the 1950s show’s premise and outcome, however interesting it was as an experiment.

Maybe the small ‘downside’ of the Whitechapel show, with all its omissions, is the flagging up of the seemingly random nature of curatorial choices of a lot of shows these days which have to pander to the big hitter galleries for one thing,, but personally I don’t expect too much. How could they possibly fit everything in if they tried to do a survey? It’s a very small gallery. I am just grateful that I can walk down road and see the beautiful art (Taeuber-Arp, Anni Albers, Popova, the Lygias, Oiticica etc.) that I thought I knew well and some I didn’t – however crammed in it is. I actually think that the curators have used some very good ‘taste’ – particularly downstairs – why not? With a bit of luck this is a starting point for some more focussed and specialist lines of enquiry. The upstairs bit that everyone seems to hate (the jokes, the questions and the tentative appropriation) is full of the ‘experimental’ and is interesting and rather inspiring. Why? Let’s move on. We can now build on, re-structure and re-invent modernism with awareness, intellect and earnestness. It is probably a stage we had to go through – and there is a some goodness there. Where would we be without punk rock? How can we move forward without aggression, without reflection? And Robin, I still don’t understand your objections to Malevich and your insistence on critiquing the black squares etc formally? It happened. He happened. He is part of our history. Suprematism was of course a bit nutty but the work was truly revolutionary and truly experimental. Not sure if anyone could really write a serious piece about a black square’s aesthetic/formal qualities. Wouldn’t that be missing the point? Absurd?

LikeLiked by 1 person

ps Yes Sam – I feel sorry for all those who missed Dynamo at the Grand Palais – 250 artists and something else! (Imagine the the whole of the Tate taken over) The contemporary artists in that show seemed to be exploring, reinventing and re-evaluating art ‘concrete’ in a much more direct and earnest way – it all felt more like a community and a real melting pot of formal ideas and propositions – very exciting! Am I right in saying British abstraction and the debates seems to be obsessed with the Americans and Abstract Expressionism and gesture – not sure why? Don’t get me wrong I love gesture and paint qualities – but not coupled with gay abandon. There is another whole world out there!

pps on timelessness: a lot of the art in that show and downstairs at the Whitechapel doesn’t date

LikeLike

I agree with Patrick that there is definitely value in abstraction in the way you describe the process (including the freedom and empowerment of the viewer in terms of giving/finding meaning and value, etc). But there is a problem with bringing politics into the judgement of the ‘value’ of a painting or sculpture.

These are my thoughts on this issue, being quite a political person myself, and an abstract artist.

The problem seems to lie in the connection between me and my work. I can see where some of my theories on politics come into the way I ‘make’ paintings. Here I would be talking about ideas associated with freedom.

Abstraction, and particularly an abstraction that is both full of complexity and variety based on some spontaneity, flexibility, and lack of preconceptions (prejudices), seems to be analogous with a politics which embraces these ideas.

Therefore, I’m not very happy with uniformity, reductionism, a levelling down, a post modern relativism, power and meaning imposed on the individual (see the artist’s or the viewer’s). So, we may be in the political ball park of a left, liberal, democratic, anarchic, something or another.

Although left of centre this stance is suspicious of an organised hierarchical group mentality socialism where the individual is lost (and they so often are). But this type of abstract art process is certainly not a conservative individualism.

But here we are talking about the process; the individual may have great politics – but what about the art?

Here comes the problem, and where Robin quite rightly has written (on another forum with regards to authenticity) that this won’t guarantee you the quality of each individual art work (i.e. the “content”).

I can gesture at my painting exhorting the political values inherent in me and therefore ‘its’ creation but it won’t guarantee the quality of the actual object: and how could it? It is a visual object to be judged by every individual with all their emotional and intellectual capabilities.

The painting or sculpture has to live its own life, its value in the hands of each and every viewer, much as I might want to believe that it has some kind of inherent political value.

I just don’t see how a work of art can have an ‘inherent’ political value.

So I paint some red arrows pushing back some blue squares (a la Dads Army intro), symbolic of some left field politics? The politics might be great…… But what about the art?!

The politics of abstraction needs a lot more exploration.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I was brought up with the idea of the geometric edifice in 20th century art as being riddled with stimulating contradictions. (heightened here in the 21st?) On one side there’s the dark paranoid criticality inherent in forms like Foucault’s ‘Panopticon’ for instance and J G Ballard’s fiction. These are dystopic visions of an advanced society with various competing elites managing their withdrawal from any kind of social responsibility through their control of architectural space, technology, commerce and a huge alienated underclass. On the other side though, we have this open to all ‘democratic’ language of geometry, somehow universal and ‘logical’- aiding the transformations of society, unfettered by the preoccupations of previous power elites and artist’s ego….. I think this old dichotomy or frisson is what makes contemporary geometric abstraction still feel very strangely potent. I’m intrigued by how all this might have been feeding back into that highly subjective and idiosyncratic art of ‘painting’ over the last decade or so?

But I also see these antithetical historical roots as underpinning a healthy critical understanding of art and society. I think modernity’s radicalism was, in part, it’s self reflexive scrutiny of our notions of subjectivity and individuation. I think these critical qualities are absolutely INTRINSIC to the production and enjoyment of good art. From this perspective the questioning of the bourgeois sense of self seems to have been vitally important to Malevich and the Constructivist’s drives and convictions. This mindset still permeated the hard edge and systems painting of the 60s.

But how are things different now? Has abstract art become an expression of conservative individualism- re asserting itself in a certain kind of ‘Libertarian’ swagger in a neo- liberal, markets driven world? Are we all whistling Peggy Lee’s ‘Is That All There Is?’ while measuring out another wobbly grid on canvas? But after the appropriationist/institutional critique mashups since the 80s- what is really new and different about hard edges, grids and systems works being made in the realm of painting (or sculpture) now?

Having said all that, I see artists like Batchelor, Sarah Morris, Gillick, and Coventry as extolling the (visually very thin) virtues of a sort of highly ‘subjective anthropology’- a term coined in respects of Mark Leckey’s work a few years back. (I personally find Morris’ films (with soundtracks by Gillick) so much more interesting than her ‘hard edged’ paintings.) Are these artists exploring the operations of power and desire that run through modern architecture and geometric imagery channeled by the mass media, governments and new media? (The baton handed to them by Halley and the likes.) Or are we being herded round their piles of ‘institutional critique’ that have been utterly ingested and neutralised by the institutions they set out to critique in the first place? And where does the painting come in to this now? I have also noted many times that I enjoy the speculative writings of Batchelor and Halley far more than their actual artworks….

There certainly are a lot of triangles around at the moment.

LikeLike

That is a very interesting take on it all, John, but as you know, I’m never quite sure what to do with ‘interesting’. Isn’t a rather large and problematic part of this whole business to do, not so much with minimal geometry’s relation to politics and the collective, but with the imaginative ambition of the individual – or the lack of it?

There are two extremes of ambition: at one end of the spectrum is a ‘career’ version, a wish to further one’s own material prospects and gain recognition; but there is also a disinterested ambition, for the discipline itself, a desire to move painting and sculpture along just that little bit, to find somewhere new, to add something to the pot and further the cause. Many abstract artists, and figurative artists before them, have mixed these two sides to ambition in differing measures. And I am sure when Malevich and his fellow pioneers developed their radical vision(s) for an art of severe and simple geometry, they did so out of a very sincere mixture of ambitious motives, combined with their revolutionary political zeal. In fact, I see their motivation as being rather bravely tilted towards the more disinterested kind of ambition, a desire to overturn the rather loathsome academicism of the time, for which they were prepared to put not only their careers, but sometimes their lives, on the line. I applaud that – but it still says nothing about ‘better or worse’, ‘good or bad’; it only tells us ‘why’. ‘Why’ is indeed often ‘interesting’, but it isn’t art. Art often contradicts such a rationale.

Nevertheless, those artists from around 1915 did have the ambition, for themselves and for painting (perhaps, as usual, less so for sculpture), and they are a part of art history because they were the first to get there. Their ambition was undoubtedly a large part of their radicalism. Good for them. I don’t like their art much (barring the occasional Popova etc.), but I see that they were ‘for real’.

Where we are now, in terms of the ubiquitous semi-geometric minimalism (with a small ‘m’), which has become almost universal in abstract painting in the last ten years, and that has been taken up by numerous younger painters, is the abstract equivalent of the Sunday afternoon amateur landscape painter from fifty years ago. Of varying degrees of talent, and blameless in every respect except for being utterly unambitious (in any sense) and derivative, these painters continue even today to uphold what they see as ‘proper’ values in art – conservative figurative values – whilst diluting the very principles which they wish to uphold. That is not to say that if you paint pretty decent and modest landscapes with a modicum of talent you cannot accomplish decent and interesting(!) vignettes that follow the achievements of greater artists from the past. And many thousands of amateur artists do just that, and happily produce millions of second-rate, but honest, figurative paintings. However, it is clear that if you are now engaged as a painter in producing ‘Impressionistic’ landscapes that mimic the breakthrough that Monet and company made 130 years ago, you cannot expect to be lauded for your adventurous ambition.

So why can we not see a contemporary equivalent happening in abstract painting now? Why are we revelling in the facile geometry and the easy-peazy gesture of dinky little abstract paintings that can be knocked off three at a time of a Sunday afternoon? Is the association with past radical politics blinding us to the reality of the work? Why are we so tolerant of the lack of any kind of ambition (apart from the obvious exceptions of the out-and-out careerists, like Morris and Halley)? OK, so this type of low-key academic abstract painting comes kitted out with hipster beard and cool attitude (a very different kind of disinterest) instead of the tweeds and twin-sets of a previous generation of ambition-less amateurs. But the only difference that I can see between copying Monet then and mimicking Malevich now is that doing Monet is more demanding. ‘Doing’ abstract art has become a piece of piss.

Yes, far too many triangles, John… and circles… and squares; and far too much of the opposite too – gestural swishes and splashes, layering and wiping-out… and all in the best possible taste. But then, we have yet to address the real question – what do we put in place of ’taste’? What content could possibly make abstract art utterly compelling, instead of yawningly banal?

LikeLike

Malevich proclaimed the end of Bourgeois society with his pure forms and zombie formalists hale the absolute domination of technology by producing ink jet images of paintings that look at first glance to be handmade. There is a critical community out there for whom that sort of thinking is catnip. I made the mistake in my article on Zombie Abstraction of seeing the zombie formalists as antiseptic versions of Mondrian when their genealogy is clearly from Malevich.Mondrian ended up with pure forms but his arrival at that extreme abstraction passed through Cezanne and Monet.To escape from this endless rehashing of formalism with Halley or the studied deconstruction of formalism in Schnabel that lead to Provisional painting and its endless dialectic that keeps repeating itself and which each new generation forgets already was done, probably requires some divine intervention and will not be easy. My thesis that all stylistic breakthroughs have their origin in deeper notions of seeing(physiologically not metaphysically although metaphysics may have to change before we see new physiological structures) may have some relevance since what that knowing will be is at this point hidden. I am guessing that it may require jumping out of all modernist notions of a painting or sculpture being self- referential.Maybe the coming together in meaning of a work of art may require a different notion of time in relation to the work of art.Something like the relation of the divine in a Fra Angelico

LikeLike

Just a general point about geometry in art as I have not seen the show sorry. I see a lot of geometries , particularly triangles being employed in painting and sculpture , in preference to squares – I have no problems with that really as it seems an approach that comes around every generation. Architecture springs to mind and Buckmeister Fuller’s geodesic support structures, which can be used to span vast areas. So many buildings, bridges, roofs use this system . There is a logic to this in structural engineering. In art, the triangle seems to have usurped the square as an intended neutral colour support – it functions to add a dynamic that the square doesn’t have (a three year old cannot copy a triangle on a regular piece of paper) – the diagonal is an aggressive line. Having said this it can lead to a complacency. Here’s a mathematical poser worth considering: is a corner a meeting of two planes or a change of direction?…the latter points to a whole different mind set, pictorially, whereas the former sits “squarely” in the world of “placed” composed configurations.

Moving on to systematic approaches in art; they force the artist to conclude a work in exactly the same way as it was started. If it’s stripes, blocks, straight edges and a problem is encountered , it will be with these elements in mind that a solution will be sought. I have worked through these issues, since my student days, so can appreciate them, and in fact it can be argued that even gestural art has a systematic approach. I am in the opinion now though that the more unpredictability that can be encountered the wider the expressive possibilities that can be achieved. Geometric art , alongside or employed with, tiny painting does run a higher risk of being viewed as merely austerity abstraction, rather than dealing with full throttle abstract art making ambition. It’s a moot point I know, contentious even, but as Matisse said (I know I overuse him!) “exactitude is not truth”.

LikeLike