Viewing the Sonia Delaunay exhibition at Tate Modern (on show until 9 August) I could almost believe that I had been transported to a time and space where decorative or applied art and serious fine art actually co-existed, having equal importance, rather than the gendered separation that was more the reality then and continues, perhaps subliminally into the present. Whilst it may no longer be that we consciously think of one as more important and therefore the domain of men, and the other as less important, being the domain of women, I could suggest that our contemporary suspicion of the decorative is an unconscious carry-over from that sexist separation of domains. It appears that the worst thing that can be said of an artist today is that s/he is “a decorator”, or that a work is “merely decorative”, which may indeed be a repressed form of misogyny. Sonia Delaunay’s designs and paintings, her fabrics and her fashion, were all part of the same project of modernity that promised to overcome traditional hierarchies like male/female and high/applied art. So, whilst what strikes me first about the exhibition is that the work is highly decorative, I see no reason to use that word in a pejorative sense.

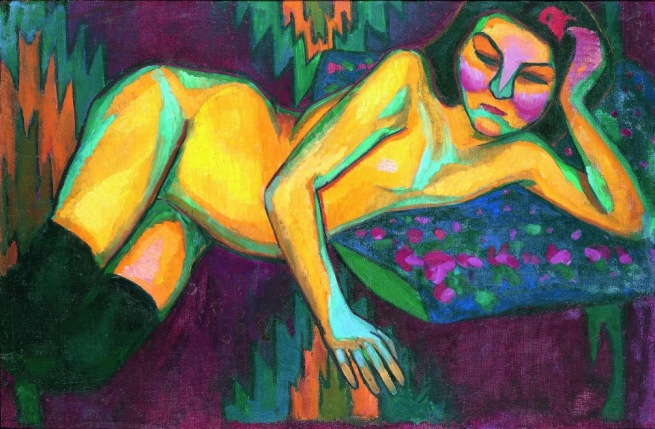

Born in Odessa in 1885 to Jewish parents and being adopted by her wealthy uncle when she was five years old, she grew up amongst the St. Petersburg bourgeoisie, learning Russian, French, German and English. Travelling throughout Europe and regularly visiting museums and galleries, she became interested in art from an early age. She studied at the Art Academy in Karlsruhe, Germany and then at the Académie de la Palette, after moving to Paris in 1906. She had visited the third Salone d’Automne in the previous year seeing paintings by the Fauves whose influence along with that of Gauguin can clearly be seen in the gallery of her early work, with her use of bold colours and dark contours around her figures, as seen in the numerous portraits and in her impressive Nu Jaune (Yellow Nude).

She married Robert Delaunay in 1910, and together they developed a theory of simultaneous colour contrasts, which they named Simultanism or Simultané. For Sonia it was also literally a brand name. Robert argued that “The simultaneity of colours through simultaneous colour contrasts and through all the (uneven) quantities that emanate from the colours, in accordance with the way they are expressed in the movement represented – that is the only reality one can construct through painting”. Guillaume Apollinaire credited him with discovering Orphic Cubism, defined as “the art of painting new structures with elements that have not been borrowed from the visual sphere, but have been created entirely by the artist himself, and then endowed by him with fullness of reality”. Yet there is some “borrowing from the visual sphere” in Sonia (and Robert) Delaunay’s work. The paintings in the second and third galleries, for example, in the process of becoming more abstract, look like a fauvist version of cubism. The figurative starting points are clearly recognisable. And this “borrowing” is evidenced in both the Delaunay’s work throughout their lives. For example, as late as 1937 they contributed hybrid abstractions to the Paris Exhibition, the full title of which was The International Exhibition of Arts and Technology in Modern Life. Sonia’s three murals with abstracted representations of a propeller an engine and a dashboard are, to my mind, the worst pieces in the show, in fact the only pieces I really disliked. My prejudices against figuration and propaganda undoubtedly influence my negative judgement of these works. I am almost as unenthusiastic about the 1925 painting of three models wearing simultaneous dresses. Perhaps it’s the unfavourable comparison that I cannot help making with Picasso’s Three Dancers that puts me off. I think her work is at its best when it is more strictly abstract, and that is as true for me in her design work as it is in the paintings, but again this may simply be a matter of personal taste.

Sonia Delaunay, “Simultaneous Dresses (The three women)”, 1925, Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid. © Pracusa 2014083

Seven years after marrying Robert Delaunay, Sonia had switched from painting to the applied arts of needlework and embroidery, which she had learned in her native Russia. So there are lots of objects other than painting on show, including a cradle cover for her son, a painted box, a mosaic, lots of textile designs as well as collaged bookbindings and covers for magazines, all of which I tend to read as abstract paintings. There is something very painterly about the cradle cover, and the two compositions for the cover of a binding for the journal Der Sturm. The patchwork method rids the works of the black outlines and line drawing in general. Instead of creating contours, black is used along with colour in roughly geometric blocks. The grouping together of similar colours creates an informal ground against which contrasting shapes assert themselves, in what Hans Hofmann would later call “push and pull” action. Seeing these, I get the impression that patchwork influenced the painting as much as the other way round.

Her merging of fine and applied arts reflects the similar move taken by many of the Russian Constructivists, though on opposite sides of the socio-political divide. The Delaunays received an income from the rental of a house in St. Petersburg which Sonia had inherited. However, this suddenly ceased when the property was seized by the Bolsheviks in the October revolution. Her concentration on the applied arts from this time created an alternative income stream whilst also demonstrating a belief that fashion and design provided opportunities to realise the new language of abstraction in everyday life. Sonia’s approach prefigured many of the concerns of the later Bauhaus and I think it could be said that she began to popularise abstraction as a style.

The Delaunays understood the implications of abstraction as a totally new visual language, the central focus of which was simultaneous colour contrast, Sonia claiming that “…the infinite combinations of colour have poetry and a language much more expressive than the old methods. It is a mysterious language in tune with the vibrations, the life itself, of colour. In this area, there are new and infinite possibilities.”

Sonia Delaunay, “Electric Prisms”, 1913, Davis Museum at Wellesley College, Wellesley, MA, Gift of Mr. Theodore Racoosin. © Pracusa 2014083

Some of those possibilities are explored in the Electric Prisms series of paintings, the large 1914 painting of which dominates gallery three and is perhaps the centrepiece of this exhibition. As a painter of modern life Delaunay was fascinated by the effects of electric lighting, especially the electric globes or mini suns that lit the fashionable Parisian venues she frequented like the Bal Bullier dance hall, and Magic City. In the paintings the electric lights have become abstracted concentric circles, splitting white light into its constitutive colours, rather like informal versions of Chevreul’s colour wheels, where complementary colours are positioned opposite each other. Delaunays use of concentric bands allow contrasts to multiply within smaller areas of the canvas, which are in turn contrasted with adjacent accumulations of circles or rainbow-like arcs of colour elsewhere, the overall effect being of a landscape of light. There is nothing systematic in her exploration; rather it is intuitive and experimental, perhaps even haphazard. I am enjoying it, whilst simultaneously wishing for fewer contrasts in one go. I find myself concentrating on smaller sections of the painting and getting interested in certain contrasts before then finding another part of the whole to focus on. I need time to look at this huge canvas, which I think tests the boundaries of the model of simultaneity. It is surely the case that one of the properties of a visual medium like painting is simultaneous presentation, in contrast to say music where duration and succession are the order of the day. However, paintings still have to be viewed and there are limits to the viewer’s ability to see everything all at once, so the strategy I choose is to parse the overall image as one might a sentence, breaking it down into its constitutive parts. But in so doing the simultaneity is compromised. Granted, I can step back at any time and get a grasp of the whole thing all at once, and also see different part to whole relationships, two things that don’t happen in music, where sequential succession of notes in time controls the listener’s experience more precisely than does the visual. Of course, I can daydream to music and no one else can really control the content that my mind supplies, though it is surely influenced. In viewing a painting I think we experience more autonomy, the viewer possibly making more choices than a listener, but what is shared is duration, despite the arguments of some artists and critics. Painting’s immediacy, beyond a certain limit, seems to me to be like one hand clapping because the moment someone views the artwork, and without viewer there is nothing, duration is introduced.

I think Sonia Delaunay was acutely aware of this limit to the simultaneous because she seems to have delighted in making images that were impossible to take in all in one go. I am thinking of her collaboration with the poet Blaise Cendrars with whom she created the simultaneous book Prose on the Trans-Siberian Railway, which I am sure I read somewhere here at the Tate, she would have been pleased if, when stretched out vertically it had reached the height of the Eiffel Tower. The use of simultaneous colour contrasts was intended to interpret the musicality of the spoken word, so we get simultaneity in parts but not in the whole. Similarly in Bal Bullier, painted in 1913, where figures dancing the Tango can be discerned within a roughly cubist space in fauvist colour, the panoramic format makes it difficult if not impossible to take in whole, a reading is best made from left to right as one might survey the scene in a dance hall, or alternatively as one might read a cartoon, it at least being possible that we witness an unfolding over time, but not so much a telling of a particular narrative as the playing of a tune, where what is abstracted is the staccato rhythm of the Tango.

Also, what happens to simultaneity when I am viewing a painting in a separate space or time to another that is similar to it and that for now exists only in my memory? I am unsure whether to think of that as a limit or as an extension to the simultaneous. Either way, Sonia Delaunay seems to have been interested in it. One of the strategies she pursued for exploring the endless possibilities of colour combinations was to work in series, in the sense of variations on a theme. There are numerous electric prisms on show here, one of them having the title Electric Prisms no. 41, so I think it is safe to assume there must have been at least that many.

She also continued to develop her interest in interpreting rhythm as colour, painting more than a thousand works entitled Rhythm Colour. I am looking at Rhythm Colour no 1076, painted in 1939. The square support is divided diagonally more or less from edge to edge forming a central X or four triangles within which are quarter circles, and semi circles in contrasting colours, which together form full circles. It is as if the colours and the forms are set against each other. It is a wonderful painting and seeing it here I get what the Delaunays were on about, in insisting on the importance of simultaneous colour contrast in their version of abstraction.

In the 1967 painting Syncopated Rhythm, also known as The Black Snake, many of the qualities I have noted are present: the use of simultaneous colour contrasts (now also including much greater use of black) that suggests the instantaneous, but set alongside considerations more associated with time-bound arts like dance and music; the painting itself being a continuation of a series and presented in a format that necessitates an experience of time duration. This is emphasised by the dividing of the work into three distinct sections: from left to right, 1) the snake like figure, 2) a section mostly of circular and triangular forms and 3) a section of squares and rectangles. The title also alludes directly to music and dance, perhaps proposing a visual equivalent, as many abstract artists have done, including Van Doesburg and Mondrian.

Sonia Delaunay, “Syncopated Rhythm”, also-called “The Black Snake”, 1967, Musée des Beaux-Arts, Nantes, France. © Pracusa 2014083

She also painted hundreds of gouaches, many of which are scattered throughout the exhibition and a set of which are brought together into one gallery dedicated to them. These might turn out to be her finest works. I am finding them engrossing, the scattered ones are even better than the ones in the Gouaches gallery, and I include some that are more associated with her design work. Design B53, 1924, gouache on paper, and the 1916 Design for Album no.1, encaustic on paper, are excellent paintings in their own right.

Designs in ink here are also totally delightful. Two tiny black and white studies from 1933, look like 1960’s Op Art. Come to think of it, there is much in Delaunay’s work that seems to prefigure Op Art, particularly appropriate perhaps, considering that it may be the only abstract art that has ever had truly popular appeal. Her questioning what might be acceptably considered a painting, or as art, seems to prefigure much of later abstraction. I don’t think I am being too fanciful in imagining Bridget Riley, Blinky Palermo and Francis Baudevin, anticipated here. I am surely overdoing it if I also suggest that her use of the series heralds reductive, minimalist and conceptualist preoccupations with modularity and repetition.

In closing, I am doing my best to re-open the debate that has been repeatedly rehearsed in these pages about, for example, the difference between design and abstract painting, and I think I am answering that there need not be one.

Reblogged this on patternsthatconnect and commented:

Read my review of the Tate Modern Sonia Delaunay exhibition over at abcrit. Lots of other interesting things there also… go see

LikeLiked by 2 people

Dear Andy,Well done ,a brilliant review of a terrific exhibition .Im conscious that much as I enjoyed the show ,there was something problematic to a painter.I think this emanated from the locked nature of design,the fact that once the pattern is arrived at,however strong ,there is little room for light,movement and speed.This seems to me to encapsulate the design /painting divide.Im sure she was aware of it ,but particularly toward the end of the show,I felt the paintings to be frozen,they didnt swing . I particularly liked all the earlier work ,including the film of her opening a box of scarves,that were no doubt innovative for her time .It would be interesting to compare this problem of a grand staticness with Brigit Rileys recent show ,which however beautifull ,suffers from the same lack of emotion expressed.I dont think this is simply a question of expressionism as Matisse manages decoration and feeling at the same time.

LikeLike

Hi Patrick, not entirely sure I know what you mean be the locked down nature of design, if Riley is an example of the frozen, the static, or a lack of emotion, then I’m all for more of that!

LikeLike

I didn’t enjoy much of this show at all. The paintings didn’t work for me and the designs were truly awful, even taking into account what was being done elsewhere at the time. Her use of colour was just uninspiring and showed a distinct lack of understanding of how to use it. I do admire that she turned her hand to design when her funds from Russia ran out and she was clearly a charismatic women. She must have been to get people to buy the clothes.

The paintings were nearly all painted with the same short brushstroke, which made them rather dull and flat. I wish she had broken the surface up a bit more by varying how she put on the paint. The colours didn’t sing for me and I think they absolutely have to with this type of work. Thinking of Klee, for example, when a small painting and a hit of colour can pull you right across the room.

A misconceived show by any standards.

LikeLiked by 1 person

There were at least half a dozen big paintings in the show which demand our attention,unfortuneatly I cant reproduce them here.Altho feeling like major statements they lack the informality of the paperworks .She was best at being Sonja when she forgot about her husbands theories and went a little mad with the colours and gaps.I feel she was aware of my cautions regarding the static quality of a finished design [whether it be for paintings or dresses]as she introduced many pencil rubbings into painted works to vary and break up filling in the boxes of colour.I feel the weight of Cubism around her neck and as Sally pointed out ,could have moved towards the fantasy world of klee or miro ,as a way out.I think the colour is wonderfull however throughout ,and without a hint of misogeny,felt she was a better painter than her husband ,with her own unique sense of peasant/ethnic richness.

LikeLike

This show seemed to sag in the middle. I preferred her work in other mediums than painting- especially some early and then late tapestry works and the floor based mosaic. I particularly liked the quilt made for her baby son, it could compete with a Klee. Funnily enough, I preferred her later paintings, they felt clearer and more to the point. The more muddy illustrational boho stuff in the middle of the show looks far better in reproduction.

Andy’s introduction asks pertinent questions about how to assign value to mediums other than painting and sculpture that may have purposes beyond the purely aesthetic. How does abstraction fit into this debate always brings up the issue of ‘decoration’ and ‘design’. I guess the show didn’t really grapple with specific issues like this or I missed it. Does anyone know if Delaunay talked explicitly about her position as a female artist and the hierarchy of art forms?

LikeLike

I enjoyed this show; perhaps slightly less so on my second visit, when some of the work really struggled to keep my interest. And I like Andy’s review here, and his honesty about what he sees and feels about the work; but I think his answer at the end of the essay about there not needing to be a difference between design and abstract painting is not right for me.

A couple of related questions, that I asked of no-one in particular on Twitter recently (though in reply to a tweet by Andy) were:

When do systems/series in abstract painting becomes formulaic?

And

What distinguishes “patterned” abstract painting from design?

Andy suggests Delaunay’s work is a continuum all the way through from painting to fabric design. I’m told on good authority that the fabric designs are first-rate and ahead of their time. Delaunay’s paintings are, in my opinion, not first-rate, but there are some that are very good, and they do appear to me to set some good historical precedents for the open-minded progression of abstract painting dealing with colour, as it develops out of the rather dour back-end of Cubism. Even so, it is not just the applied art of Delaunay’s work that is designed; a lot of the painting is too, prescribed by varying degrees of rules, systems and limitations and pre-determined sets of geometric shapes, mostly set out by way of drawing. When they exhibit less of this tendency, I like them more, as in the very early figurative work – “Yellow Nude”, for example, is terrific in its barbarism. I liked, to some extent, a couple of the paintings from the Portuguese Market, which are also figurative, but which have subject matter that chimed with her ongoing preoccupations (circular fruit etc.). My favourite work in the show was a piece of figurative embroidery (for which I can only find a poor B/W reproduction https://www.pinterest.com/pin/551902129310023855/ ), which I thought was the most excitingly abstract thing in the show. I know that’s crazy, but as a pictorial object it constantly lost its representational subject and redefined itself in any number of structural directions, in a manner very close to what I now might expect of advanced abstract art. It certainly engaged me more than the later paintings, which, like Patrick, I found rather wooden. I would say that her use of colour in painting gets progressively weaker, and the drawing/composition over-determines the outcome of the work more and more, as you go through the show chronologically. I even found the initially exciting large “Electric Prism” painting of 1914 http://www.pbase.com/chammett/image/143219835 , her tour de force, mildly disappointing after sustained scrutiny, with the whole section across the top starting to look rather redundant.

There may well be in Delaunay’s work a continuum between applied art and fine art; but I would say that that continuum does not extend to anything near the fullest potential for painting. I cannot help but think that the geometry and a preoccupation with applied art and pattern-making, along with the theorising about that continuum itself, may have contributed to a deficit of quality. This is not a snobbish thing about fine art versus applied art, and it’s certainly not misogynistic. As I’ve said many times before, lots of textile art and quilts etc., are superior to much that abstract painting can offer; I know of no geometric abstract painting that has the variety, complexity, outstandingly rich colour and outright original visual excitement and vitality of any number of African-American quilts, particularly those from the first half of the 20th Century, e.g. http://xroads.virginia.edu/~ug97/quilt/atrads.html . At the same time, those very quilts will not stand comparison with the very greatest painting from history, and for exactly the same criteria. The quilts are limited by their geometry, their repetition (though the best of them ingeniously usurp and disrupt the expected ordering of the patchwork), their literalness of surface, and their limited spatiality, in ways that great painting is not. Great painting exhibits great freedom of expression in a manner impossible for design of any kind to embrace. Maybe painting’s potential for such a unique and special brilliance is an illusion, but it remains a potent one; “the illusion”, to quote Howard Jacobson, “of plenitude”.

So for me, systems and series and design and repetition are factors that limit painting. Those limits would seem to suit the sensibilities of a lot of abstract artists at the moment, who are happy to work to rules and regulations, and within the precincts of things we know about already; and this tendency chimes with a general heightened awareness of aesthetics and design-related issues. But I want more – much more – out of art than a consolidation of contemporary taste. I can’t personally see how the simplifications applied to painting by a proximity to applied art can be extended to embrace the necessary multi-tasking, self-redefining, configuration-busting complexity that will allow abstract painting to be on terms with the best of figurative work from the past – or indeed, deliver some new terms altogether.

LikeLike

Robin, it is interesting that you use the term ‘Great painting’ when quoting Jacobson. Because Jacobson actually says “…art releases the illusion of plenitude.” He doesn’t even use the term ‘painting’ or ‘Great’ either. Also he goes on to talk of Matisse …..

“Think of the aged and bed-ridden Matisse cutting out strips of coloured paper, much as a child might, and investing them with a more than mortal vitality … Those strips of paper resonate because they prove that our materials don’t determine in advance the worth of what we make.”

So it seems for Jacobson ‘Great’ art can be made out of anything.

As for the “best figurative work of the past”, it is interesting that painting was given such intellectual pre eminence in the Renaissance. Alberti suggested that the painter deals “… with more difficult things” than the sculptor for instance. I certainly don’t believe this is a relevant position to take at all, but I wonder how much these hierarchical values still persist into the present tense?

LikeLiked by 1 person

I guess that if you care about the ‘visual’ in visual abstract art you will not be so concerned about the material. Paint is a great medium and also one we are used to so it works well in creating the illusion of something beyond itself; a successful work seems to work as something in itself, going beyond the material, i.e. paint.

If your going to use all sorts of stuff to make your visual art you may run into some difficulties, challenges, in being succesful, but that might be because the material has meaning (as subject?) in a different way that paint has.

As abstraction has a relation to freedom and I like to keep focused on the object I wouldn’t want to close down the types of materials we should use.

LikeLike

I’m not sure Jacobson does make exactly the point you want him to make, just as he does not quite make mine. The fact that materials don’t determine worth doesn’t necessarily mean that any material WILL make great art.

I liked this article by Jacobson (his RA speech, I think), and to continue your quote, he goes on:

“In art, where we play in order to discover, there is no “in advance”; no intentionality that will survive creation; no thou-shalt-nots advanced in the name of religious or social rectitude; no theme so important that it will of itself confer importance on a work, or so apparently trivial that it won’t; nothing – in the language of social media – to like or not like and press a button to show which; nothing, in online-speak, to agree or disagree with and tick a box – for you can no more disagree with a painting than you can a flower. No certainty other than the certainty that we can’t be certain of anything.”

As makers now, we can be sure of nothing. But maybe one can be more certain (even of heirachies) after the event. What I certainly don’t believe is that everything is equal; heirarchies are important to think about, so long as they remain open to change.

LikeLike

Lots of great stuff there ,Robin ,which I agree with .Just a note for Andy,tho,about simultaneity.I immediately took it to refer to what Josef Albers developed into the Interaction of Colour.Which means the reds and greens ,when abutted in the arcs of Orphism,reacted to each other at a similar speed of mutual interaction.I found that exciting and confirming.However ,as John mentioned ,we need an art historian to set us straight about the Delauneys original attitudes and intentions.With Paris ,Jazz,and Modernity all around ,you wouldnt expect the work to be wooden,as Robin puts it very well.Has anybody got a pocket definition of Simultaneity?

LikeLike

Following on from Patrick and John’s comments. From R & S Delaunay’s texts it is clear that they thought of Simultané as being about simultaneous colour contrast in the same sense as Albers later, and Hans Hofmann also, who specifically named the Delaunays as an influence. Roberts Delaunay made a number of statements in which Simultané seemed also to be about the instantaneous presentation of painting as opposed to time based media like drama and dance. He could sound almost scathing about the other art forms when comparing them to the instantaneousness of painting. (At other times he used musical metaphors for abstraction, perhaps wanting to have is cake and eat it. Alternatively this is one of those cases where opposites can both be “true”.) I think in this respect the Delaunays were quite close to Greenberg. It also clear from the texts that Sonia never saw herself as a follower of her husband’s theories but as a co-creator, that she believed her work deserved recognition in its own right and she at least implied that she was slow to get that recognition because of her gender and because of the hierarchy of art forms. That was my reading of the texts anyway. As for a pocket definition, I searched but did not find.

LikeLike

Dear Andy,I did find a definition in John Goldings Cubism ,which confirmed that Simultaneity referred to Colour.To paraphrase, as I dont have it with me ,Delauney made a case for placing four pure colours in a relationship where they fired off each other sufficiently to create a possible fifth,creating light.His Orphism was considered by Apollinaire to be the most Abstract as it didnt need external reality to be depicted,however analytically/destructively ,like Cubism.In fact his Abstraction had to be given its own reality by the artist,using the purist means of the Painter,Colour..He was therefore the precursor to Colour field Painting and Greenberg,altho in reproduction his paintings look a little dull.Frank Stella created the most wonderfull homage to Sonja in the Protractor series ,which were exhibited in the Hayward in the 70s and made a huge impression,fifty years after Orphism .

LikeLike

Firstly I’d like to congratulate Andy for such an excellent, thorough, hard-wrought piece of writing. I also really enjoyed this show . The appliqué pieces and embroidery in the clothing with their tactility of colour were my favourite. Design has a functional intention. Graphics is the visual communication of information. Painting has got caught up in a Venn diagram with these other disciplines. ‘Abstraction’ always seems to work within a received vernacular and as such is rooted in taste. Delaunay comes over as a really sensitive handler of colour who realised her refined taste best in design.

LikeLike

Do you think, Emyr, that abstraction is limited indefinitely by that received vernacular and taste, or do you think that it has been, or can be, broken out of?

LikeLike

Where to start on that…

I worked within a “flattened” vernacular approach for many years – things ticked along just fine, however it slowly dawned on me that I was unable to connect with the art that I was most inspired by. Also I noticed how I was struggling to get an expansive space into my work.( still a challenge) The two things were the part of same problem. It leads to smugness when you should be feeling bewildered.

The hope is not just to make work that gets beyond taste and received tropes but to find an audience that wants it! We are possibly in an age of display rather than engagement. Our education system is not helping either as rather than promoting questioning, it is promoting answering. I think it was ever thus though.

Collioure was a destination for Matisse to escape the “bewildering cross-currents in Art” . I am not advocating going there to solve any problems (though it has great ice-cream!) but the principle of shutting out the stylistic maelstroms and dealing with the fundamentals would seem a good starting point.

I touched upon this in my homage article I think,: “me too” is already one too many.

If its not origami abstraction, its watercolour challenge abstraction. I said a long while back on one thread on abstract critical. If you had to start from scratch, what would you aspire to make? I think it is very hard to make a colour space painting. For one thing you sculptors have the air , we painters have to create it!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fascinating Emyr.Ill take up the “hard to make a colour space painting”.Thats exactly what Ive been trying to do,partly in response to Robins demands on Abcrit for a deeper non-figurative space.Its bloody difficult when using Colour as the arbiter.Individual colours while reasoned out of judgement and experience ,just tend to do their own thing.This creates havoc with relationships and when making the inevitable changes,the surface goes,which is also vitally important .Ill be showing them for discussion at the Brancaster,but will have to pull something out of the bag,as I havent got one coherent picture after 9 months work. Ive got some bits ,however which glimpse what might be possible. and am enjoying the process.Its so different than the Greebergian model of a shallow ,non recessive space.Quote from Golding after Sonja”Pure colours used as planes are juxtaposed in simultaneous contrasts to create for the first time a sense of form,not acheived by clair-obscure,but thro the relationships in depth of the colours themselves.

LikeLike

‘If you had to start from scratch, what would you aspire to make?’ how freeing! so much of my decision making is held back by my own art practice history. what inspires me to now is different to what inspired me when I began to make work, however, it’s difficult to change the tracks. I’ll keep this phrase in mind for the times when I feel I’d like to.

LikeLiked by 2 people

For the Tate to, fortuitously, be overlapping Agnes Martin’s exhibition with Sonia Delaunay’s creates a Simultaneous contrast of sorts that should invite visitors to, ideally, see both shows on the same visit. I must admit that my first viewing of the Delaunay (before the Martin opened) left me impressed with her painting practice, but indifferent to her fashion related design. Andy Parkinson’s excellent review on Delaunay has made me think again and I would agree, that “… her work is at its best when it is more strictly abstract … in her design work as it is in the paintings…”

If there remains a debate on the difference between design and abstract painting, Andy’s conclusion “that there need not be one” is perhaps pertinent on a purely visual level, with the applied functionality of, say, a textile print being disposable if the visual hit is sufficient in itself?

Does excellent visual design aspire to the condition of fine art?

LikeLike