Jackson Pollock: Blind Spots at Tate Liverpool, 30 June – 18 October 2015

‘I don’t paint nature, I am nature’ is only a couple of stops up the art historical track from ‘It’s art because I say it is’ and only a few more stops down from ‘Pollock blew the picture to hell’1. But what if we get off this particularly well ridden bandwagon of art-speak clichés? We are used to those grindingly repetitive narratives of courageous innovation leading to a numbing bubble of celebrity, crippling self doubt and full-blown self destruction. I was hoping this show might help in beating a new path toward fresh and original ways to apprehend Pollock’s later art.

Jackson Pollock: Blind Spots at Tate Liverpool did not start with a painting but with a small photograph. We are told it’s an image of a mother and child. Areas of the two entwined bodies are blotted out by the artist with black ink. Other areas of the grainy creases of skin, limbs, hands and eyes are left exposed. The image has at once been destroyed and remade, obscured and revealed. And it is interesting that our ideas of Pollock, the person and the artist, are so utterly entwined with photographs and film. These famous images have indeed created peculiar ‘Blind Spots’ of their own. They introduced a wider public and fellow painters to a new and emphasised exploration of an artist’s processes and materials. They de-mystified the way the artist worked while at the same time re-enforcing the myth of ‘Jack the Dripper’. Pollock and his art were transformed into a series of consumable images and a lifestyle package (‘flawed genius’ having its own particularly enduring history).

‘Number 7.’ 1952. Enamel and oil on canvas, H. 53-1/8, W. 40 inches (134.8 x 101.6 cm.). Purchase, Emilio Azcarraga Gift, in honor of William S. Lieberman, 1987 (1987.92).

But there are many more contradictions that continue to bounce round this particular darker echo chamber of art history and ricochet from wall to wall in this fascinating show. On the one hand we have the idea of Pollock providing some kind of near realisation of Greenberg’s dream of a truly modern painting that has finally jettisoned all literary, extraneous content and the pictorial mannerisms inherited from European modernism. On the other, we have the idea of painting as primarily a record of an ‘event’, becoming the literal trace and documentation of a performance/process/action. But this show gives us a way in to a more difficult and demanding aspect of Pollock’s art, lying beneath this tumult of myth and reality, art history and hearsay.

The first room goes on to suggest that for all the legendary guttural angst of the man himself, Pollock’s work during the late 40s was less about tortured ‘touch’ and more about pace, grace and bodily rhythm. It was interesting seeing Summertime: Number 9A, 1948, again in this new (if a little cramped) context. I was immediately struck by the delicate and highly sophisticated rhythmic structure in the all powerful and graceful black line. But I was also struck by the rest of the painting’s very conventional organisation. Tan coloured dabs proliferate right along the bottom fifth of this long thin canvas, quite literally grounding the gestural black whiplashes of paint that so elegantly bounds across the surface. It’s seemingly free flowing and improvised twists and turns are politely anchored down again by repeated blue, yellow and red fill-ins, all firing off in very neat syncopations across the painting. But with Number 3: 1949 Tiger, 1949, we get that process-driven attempt at keeping up a constant, scintillating, dynamic activation of the entire surface of the canvas. While painting on the floor, gravity becomes a resource to aid an open and more flowing use of paint. Rhythms can be conjured from a constant flow of line over line, always pushing out to the edges of the canvas. We can see how Pollock is keeping every inch of the surface alive by the weaving of negative and positive spaces. We are left to revel in the electrical charge of these attractions and repulsions therein. The stick or brush doesn’t have to touch the canvas and the paint runs as a viscous string across the surface. Holding its form as it is flicked and flung, it moves over the accumulation of other marks that have found their way into the painting. Colour can then hold to the line and find new shapes, or break with it, firing off a whole different set of dynamics and spatial play above and below the pulsing, curving aluminium and enamel striations.

I think it’s a shame we didn’t get the chance to see one larger scale ‘all-over’ drip work from the late 40s. We would then be able to examine the contrasts with the later ‘black pours’ more thoroughly. The pre 50s morsels on offer here suffer somewhat from their restricted easel-orientated dimensions. But they do suffer in interesting and tantalising ways. In Two-Sided Painting, 1950-51 ‘touch’ re-emerges as black enamel scratches that rip up the otherwise languorous poolings of aluminium. Here, I think, are intimations of what was to come.

The works that follow in their totality focus down on the power of line and the inherent drama between the black and the white therein. Just like the little photograph at the beginning of the show, it’s all about what is hidden in the darkness and what is revealed. But there is a highly distinctive duality at work still, almost all the way through the show. Number 23 of 1948 is so supple, subtle and elegant in its effortless dance of silver, black and white on gesso and cream paper. It warrants artspeak like this by Michael Fried.

‘…there was the notion that at the heart of his all-over canvases was the attempt to prise line loose from the task of figuration.’2

We also see intense experiments with different kinds of surfaces and how they affect the qualities of line and the spaces it can summon up in the surface. A room is dedicated to works created using Japanese papers. They are delicate and ethereal. The relationship between application of paint and the surface qualities of the paper are beautifully realised. There are also experiments with silkscreen. It’s interesting to see motifs that could be repeated and hung as groups of images. But it feels to me that Pollock was beginning to sense the limitations of what was to become very quickly an intellectualised strategy and a formulaic set of painterly ‘special effects’.

Listen to a rather tense and speculative Greenberg from a few years earlier in 1948: ‘[The] dissolution of the picture into sheer texture, sheer sensation, into the accumulation of similar units of sensation, seems to answer something deep-seated in contemporary sensibility. It corresponds perhaps to the feeling that all hierarchical distinctions have been exhausted, that no area or order of experience is either intrinsically or relatively superior to any other… the only valid distinction being that between the more and the less immediate.’ 3

But it is the ‘Black Pourings’ that are the throbbing dark heart of this exhibition. Crude materiality and brooding imagery seems to be answering something very different but equally ‘… deep seated in contemporary sensibility.’ Pollock’s ‘gothic- ness’ that had always disturbed Greenberg re-emerges to assert its power. But these black works have gained some kind of momentum, some new kind of febrile and focused intensity. They seem to be an attempt at extreme synthesis rather than meticulous refinement; a synthesis of personal obsessive renderings of the fragmented body, that had always lay hidden in the ‘all-over’ works, combined with, and intensified by, the technical innovations he had made while working upon the drip-based paintings.

‘Number 14’, 1951,

Oil paint on canvas

support: 1465 x 2695 mm frame: 1493 x 2721 x 63 mm

© The Pollock-Krasner Foundation ARS, NY and DACS, London 2015.

Number 14, 1951, has certain structural echoes of She-Wolf from a decade earlier. She-Wolf might have seemed clunky and overloaded with esoteric signage uncomfortably lodged in a shallow representational space. But Number 14 is a hypnotic molten surface welling up with a constant churning-over of imagery. This is the realm of painted shadows and shadow selves. This is the realm of Picasso’s Three Dancers unleashed from a stage set cubist space that had so rapidly declined after Guernica into the dominant pictorial mannerism of the age. This new dance, though, is one of constant metamorphosis. Flailing body parts – heads, eyes, hands – are emerging from the warm, heavy and tar-like blacks. These pours and stringy whips of enamel are providing a rich gush of startling pictorial invention and a different kind of ‘all-over’ cohesion. Before, in the drip period, any imagery remained veiled or pulverised. Now submerged images are wrestling for realisation. And we feel right there in the middle of the clots, the bleeds, the flinty black coils and the soft flows ebbing into bare cotton.

Picasso, at his most vicious, takes his almost polite cubist spaces gleaned from the quotidian world and collapses the rooms, the furniture and architecture into his subjects’ faces and bodies. Pollock understands this idea of painting becoming some kind of dynamo for invoking transformation, but drew this power out from the peculiar qualities inherent to the mediums he experimented with. It seems to me that as Picasso got older he could always ground his own obsessions in well worn myths, in cheeky plagiarism and jaunty tussles with the past giants of art. But Pollock seems in constant conflict ‘… between the more and the less immediate.’ In Black and White Number 15 there is a beautiful tension between what is being blotted out and what is still writhing to the surface. Number 7, 1952, is an elemental heavy head-like form, yet it is melded from sophisticated and airy visual rhythms. The enamel blackness becomes all static electricity, charged up by its dynamic friction with the bare canvas. At their best, many of the black paintings, in what feels like the slightly claustrophobic molten core of this exhibition, have surfaces that seem to physically pulsate around one. I think the achievement is more complete and compelling in the enamel -based works, rather than those in oil.

I don’t think this is just an artist trying to achieve some kind of Jungian epiphany either. The ‘Black Pours’ feel like a real exploration of what these wholly modern enamel paints can do in a raw battle with the weave of the cotton. Something of this surge of protean energy goes on to be harnessed to great effect in Number 12. But here, back in oils, colour is allowed to assert itself again. Billowing clouds of luminous blue and smouldering yellows divide up the canvas. Craggy and crusty blacks claw and dig out ravine-like spaces therein. The eye is caught by a snappy surge of dirty turquoise and bloody red splashes. But all this is tempered and channelled by that whiplash line. Always so suggestive, but always, it seems, one step ahead of me – continually opening up the surface of the painting.

The most disappointing aspect of the show was the meagre offerings of Pollock’s experiments in sculpture. There just weren’t enough pieces to be able to see how he might have grappled with this artform. There are definite moments of potential in the spiky play between the inert bony fragments of plaster and the dirty wires that writhe through them and around them. But the interesting interpenetrations of forms in these small pieces of work were lost in oversized glass boxes. These boxes contained highly reflective floors on which the sculptures sat. The reflections created seemed unnecessarily theatrical and did nothing but confuse and disrupt the viewing of the work.

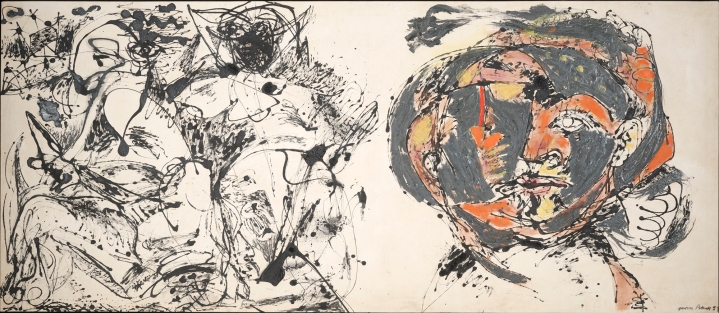

‘Portrait and a Dream’, 1953

Oil and enamel on canvas

Overall: 58 1/2 x 134 3/4 in.

Dallas Museum of Art, gift of Mr. and Mrs. Algur H. Meadows and the Meadows Foundation, Incorporated

© Pollock-Krasner Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

And so it seems that Portrait and a Dream, 1953, is a kind of final self-reflexive musing on the contrary and conflicted yet fecund centre of Pollock’s later art. The left-side tangle of imagery has been likened to a woman giving birth, a wet dream, and a matriarch decapitating chickens in America’s ‘wide open spaces’. The bloated, bruised and disfigured head on the right takes a rather bemused side-long look. Like us, it can only catch a glimpse of the hypnotic writhing tumble of lines as they unwind, cascade, kick and bleed their way across the canvas. They all at once suggest some kind of ecstatic sensation of pure horror mixed with pure joy, but then it all evaporates back into the surface of the unforgiving fabric of the canvas.

We are so used to getting our abstraction ‘once removed’ these days. The disengagement of the brush from the canvas that Pollock’s myth made infamous has once again been released from the box of art history. Here though, Pollock’s late works resolutely refuse to be reduced to a set of ‘procedures’.

I couldn’t help but think of Tate Modern’s new room called Painting After Technology. We are told: ‘Many of these artists [in Tate’s new room] are also concerned with working within or against the established traditions of abstraction. Abstract Expressionism was often associated with the heroic male painter, each brush-stroke supposedly a trace of his emotions. How might gestural painting be pursued when this narrative is distrusted?’4

How indeed? ‘Blind Spots’ makes me think that Pollock, out of all the Ab Exs, was navigating this particular quandary and finding something very different and very new there. He was already questioning what rapidly became the pretty cul-de-sac known as ‘lyrical abstraction’ (a catch-all that cultivated a multitude of sins). As for Ab Ex’s ‘second generation’? ‘The Tenth Street Touch’ became a code name for derivative refinement and a whole new kind of pictorial mannerism.

I think it’s a poignant irony that just 5 years after that famous film being made of Pollock working, he should go on to die in the manner so like one of Andy Warhol’s car crashes. Messy newsprint repeated in faded silkscreen in that ghoulishly deadpan fashion would soon become de rigueur. The world was changing and so were the tastes of the people changing it. Warhol and Pop Art generally would go on to dominate art discourse as many of the original irascibles seemed to succumb to some kind of personal tragedy or other.

And this is the rub for me. We live in a time when notions of the authentic gesture and the power of the artist’s indexical mark are held with deep suspicion. Warhol and his heirs have taught us to keep on the surface of things. Stella and the minimalists said ‘what you see is what you see’. But the ‘irascibles’ kept implying a deepness, no matter how much the flatness of the picture plane was asserted. They kept asking how painting, in new and extreme forms, might connect to a deeper sense of ‘us’, to the seat of our fears, longings, our contrary, conflicted modern selves. So, did Pollock’s fame and fall hail the beginning of the end of a last flare up of an anachronistic painterly romanticism? Well, no. Did his late works defiantly spit in the faces of both the ‘Old World Europe’ and the rising giant that was corporate America (and a couple of its more venerable ‘Modernist’ art critics to boot)? For sure. But like all great art, it was full of fascinating contradictions and near miraculous synthesis, wholly unpredictable and still full of irrepressible, frightening, future-focused vitality. Very ancient and very modern. Very human.

1. Part of a phrase attributed to de Kooning, I think.

2. Fried, P57 ‘some new category: remarks on Several Black Pollocks. ‘Blind Spots’ Cat.

3. Greenberg, “The Crisis of the Easel Picture” [1948], CEC, 2: 221-225; 224-225.

4. Does this little tit-bit whet your appetite or put you off your dinner? Go see Tate Modern’s room called Painting After Technology. It includes artists such as Christopher Wool, Charline von Heyl and Albert Oehlen… Tell Abcrit what you think!

John has reviewed this show with great understanding and depth, it is a clear, well written essay , I almost don’t need to go and see the exhibition !

LikeLike

I would caution Noella,as this is just one artists point of view.It looks like a stunning exhibition from the pictures and Id love to see it in the flesh.Its going to take quite a bit to get Pollock to be totally re-assessed.John does a great job of wetting my appetite.The reason Pollock is so respected is hidden in the work .You just have to trust your own radar to find it .It doesnt get much better than this ,no matter what century we are in .This is great Art,which is still unsurpassed by any of our current pre-occupations

LikeLike

i keep saying this: simply do make that trip to Liverpool and see the show. it’s a once-in-a-lifetime and you’d regret it of you let it slip by. If painting is significant to you, go!

LikeLike

That’s a terrific article, John- thanks. And it looks like a fascinating show, and a dispiriting contrast with Tate Modern’s Painting After Technology room.

LikeLike

I thought this was an excellent show. Much of the work made me think of the Japanese ‘notan’ approach of balancing black and white; sometimes a subtlety of colour would creep in or cool whites were used as an extra to the canvas buff. There was an infrequent use of colour throughout and it really grabbed you when it came. Much of the work had an aggressive jostling at the edges. “Summertime” which floats in the middle by contrast, looked so much better here in this smaller space than in the Tate Modern. I was also intrigued by seeing his forays into printmaking. That first photograph was actually an ink collotype and there were fine examples of prints too. The sculpture looked a little lost, interesting rather than memorable. I can appreciate Greenberg’s use of “Gothic” too. Much of the work was wilfully dramatic, perhaps employing his own vernacular in a self-conscious way. My father used to joke about his mother-in-law : ” she’d put a cushion down before fainting”…. I also couldn’t help but compare these to Picasso. These are more fluid in organisation though, wrestling free of cubist structures yet still clinging to a figuration, and they really tear out at you. If Picasso’s drawings had the feel of an echo in a chateau , then these were like an echo in the desert. Worth the trip… Great stuff.

LikeLike

Thank you for an excellent article. You have made me see the 1951 Pollocks in a new light, as much more than a technical breakthrough that opened doors unrecognized by the artist himself (in Michael Fried’s opinion) but creatively exploited by Helen Frankenther with her soak/stain method. To clarify what is truly human in abstract art is no easy task, and I appreciate how well you have done that.

Nonetheless, for me the great poured-and-spattered all-over works of 1950 are still the height of Pollock’s accomplishment, and their humanity has been decoded as well. I was grateful to the Tate Modern for the audio commentary posted beside their Pollock (which in my opinion is not a great one). It implied that Pollock’s choice of his signature method was not simply his critical assessment of an opening left unexploited by Hans Hofmann and others but rather an unconscious attempt to positivize a painful experience – the accidental severing in his youth of one of Pollock’s finger tips with its frightening spurt and flow of blood. There are other analyses as well.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I am delighted with this re-assessment of Pollocks work.I never did buy the failed genius idea,finding almost everything he made extremely engrossing.I took my son Luke to East Hampton station,hired bicycles and made a pilgrimage to Pollocks home on Fireplace Road.It was empty,being looked after by Stony Brook University .so we peeked thro the studio window,with the reverse image of Blue Poles on the floor .We went on to find his tombstone ,Luke fell off his bike and required medical attention,but it was worth it.Greenberg ,in his cups of an evening ,always spoke with extreme fondness for Pollock and Hoffmann .They were the real deal ,you could sense he missed them,if not who he was when he was with them.

LikeLike