William Gear, ‘Autumn Landscape’, 1950. Copyright the Artist’s Estate. Image courtesy of Tyne & Wear Archives & Museums, Laing Art Gallery

William Gear: the Painter that Time Forgot is at the Towner Gallery Eastbourne, 17 July – 27 September 2015; at City Art Centre, Edinburgh, 24 October 2015 – 14 February 2016.

A Radical View: William Gear as Curator 1958 -1964 is also at the Towner, 9 May – 31 August 2015.

William Gear: A Centenary Exhibition is at the Redfern Gallery, London, 16 July -5 September.

Stockwell Depot 1967 – 1979 is at the University of Greenwich Galleries, 24 July – 12 September 2015.

Hans Hofmann Catalogue Raisonné is recently published in the UK by Lund Humphries.

At the Same Time as Now.

The Towner and the Redfern are both presenting the work of ‘forgotten’ artist William Gear, an associate of CoBrA in the 1940s and a controversial painter in his heyday of the 1950s. Also showing is an exhibition of the works acquired by Gear during his tenure as the Towner’s curator (1958-64), including paintings by Sandra Blow, Alan Davie, Roger Hilton and Ceri Richards. Gear fought battles with Eastbourne Town Council to get modern art, and in particular, new abstract painting, into the Towner collection, the outcome of which was to make it one of the leading contemporary collections in municipal gallery/museums at that time.

Gear’s very own version of a public outcry over contemporary art had happened a decade earlier in 1951, when his painting Autumn Landscape was awarded the Festival of Britain Purchase Prize, paid for out of the public purse, and attracting the ridicule and faux-outrage of the press. It’s hard to see why, since it looks now to be the most good-mannered of abstractions, and by our experiences of contemporaneity, unconfrontational. A lot has changed in the last 65 years of art; the position of always equating ‘now-ness’ with newness is well established (they are, to be fair, often difficult to differentiate), as one novelty project succeeds and eclipses another. If there is any value left in contemporaneity, it has to be more than just the next new thing, and certainly more than a rehash of what has gone before but is now forgotten.

William Gear, ‘Composition’, 1949, Purchased 1991 http://www.tate.org.uk/art/work/T05850

I make that last comment because I was brought up short recently on seeing a reproduction of Gear’s Composition , painted in1949, which looks exactly like a lot of ‘Contemporary’ abstract painting. This kind of work is usually a loose scaffold of painted lines (triangles are favoured) or planes, in a few earthy colours, that may or may not represent some kind of three-dimensional object – maybe even an abstract sculpture, or something vaguely architectural – in a scant landscape, with vestigial references to three-dimensional space. There are a number of paintings like this in the Towner’s Gear show, but his were painted around 65 years ago, and have the excuse that it hadn’t been tried much before (though an origin in the Cubism of Picasso and Braque seems likely). On Gear’s part, it was a rather timid excursion into, and retreat from, the somewhat fuller – though I would argue still partial – involvement with abstract painting and process that his American peers were getting into (Gear showed with Pollock in New York in 1949, but was scornful of his drip technique). This kind of painting by Gear, and the work that unconsciously mimics it today, is more of a representation of something (like a sculpture) that is non-figurative (because it is not a figure), rather than being fully abstract (starting out from nothing, without a subject-matter). Whatever the reasons behind its recent re-emergence, it has a similar timidity to Gear’s, and is even more regressive now than it was then.

William Gear, ‘Tree’,1947. Copyright the Artist’s Estate. Photographer Antonia Reeve. Image City Art Centre, Edinburgh

In the flesh, Gear’s paintings are much more worked, much less ‘provisional’, much less archly slapdash, than our present-day practitioners. But then the latter have had the benefit, or more likely its opposite, of the years of deconstruction of the processes of painting, from Pollock through to Oehlen and beyond. Gear knew little of that, and would, you feel, have loathed it. Gear does not do ‘casual’ or ‘provisional’ or even gestural. In fact, it is hard to find in all of his oeuvre a genuinely relaxed-looking moment, when the assumed dignities and diligences of being a fine-art easel painter are abandoned in favour of something more loose and instinctive. Even the more contingent of his images look pondered and preened, fully worked-up and over-worked. So deliberate and relentless is this designing-out of spontaneity from the picture, with never a moment’s relaxation, that I almost started to warm to him out of a perverse admiration for the cussedness of it all – almost. And whilst we would do well to be wary of attributing the expressive qualities of a work directly to the state of mind of the artist, in this case Gear’s unbending self-possession does seem to have brought about paintings that are hard to warm to, unless one is of a wholly uptight intellectual persuasion. His bearing may serve as an interesting corrective to the lax cod-amateurism of many contemporary painters, but it nevertheless remains that all his concentration and hard work end up taking his own abstract painting into a kind of cul-de-sac. Thus, his late paintings are concocted beyond endurance, a kind of garish and aggressive wallpaper, without space or life. Quite ‘Contemporary’, then.

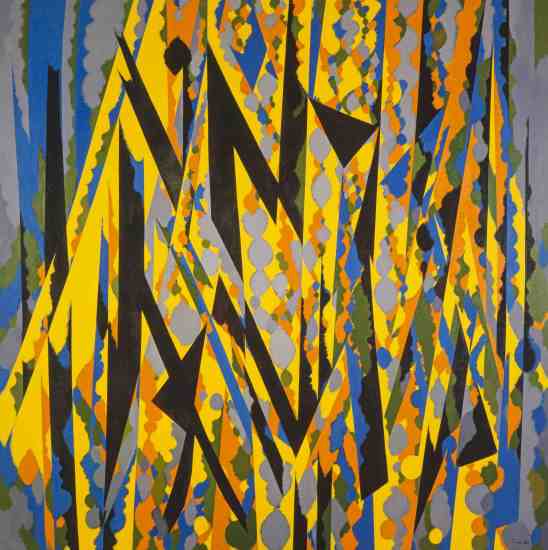

William Gear, ‘Broken Yellow’,1967. Copyright the Artist’s Estate. Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art

Andrew Lambirth writes enthusiastically in the Redfern Gallery catalogue that Gear, along with William Scott, Peter Lanyon, and Roger Hilton, was ‘part of a generation involved with painting as painting’. Ha! Where have I read that before? Does every generation have its cohort of painters painting about painting? Bloody hell, it’s meaningless! I wonder if Titian, Tintoretto and Veronese were doing it? None of Lambirth’s list are really abstract artists (though they all, to varying degrees, abstract [the verb] from figurative sources); yet Lambirth continues: ‘Gear spent formative years in Paris, and there he experimented with the abstract properties of paint.’ Well, just what are these oft-cited ‘abstract properties of paint’? Is it abstract when it comes out of the tube? Is it differentiated in some profound way from toothpaste or salad cream? Surely ‘abstract’ can only be applied to paint when it is engaged purposefully within the visual activity of a painting; and then you are no longer talking about the literal materiality of paint, but about the active content of the art. It’s a nice confusion; a conflation; a complete reversal even, of what is literal with what is abstract. Isn’t this a very similar confusion to the one about real abstract art not representing anything, so therefore it doesn’t mean anything, it just kind of ‘is’? And then this supposed quiddity, which you somehow empathise with by means of all the senses and some very iffy French philosophy, can have all manner of subjective significance, allusion and metaphor attached to it by the viewer, without fear of contradiction, in order to relate to it in some non-visual (and invariably sentimental) manner. In which case, the more simplistic the art, the more easily it lends itself to such doubtful paradigms.

That particular standpoint makes Gear’s rigour seem positively intelligent. I get the sense that he strongly aspired to get his paintings to summon some kind of particularised feeling – a sense of a landscape, perhaps, which he himself had felt and experienced, and which he desired to capture, and which would be built into the work by him, rather than casually attributed at a later date by the viewer. I admire the specificness and determination of that vision, but I think the results fall short, for reasons both of his inflexible sensibility, and for the crude state of development in abstract painting at that time, to which he was wedded and past which he was ultimately unable to travel. Contra Lambirth, Gear was unhappy to take the road of ‘painting as painting’, but could not see past it to a point where properly articulated abstract content might carry real meaning of its own accord; and consequently he opted to back off into a figuration of ‘abstract things’. It’s too much of a compromise to be great art, and it’s symptomatic of a significant moment in abstract art’s development, and one that has been revisited more than once over the last hundred years, as if it’s a place that’s difficult to get beyond. The symptoms are disquiet about the possible lack of meaning when subject-matter of any kind is abandoned, a failure of belief in the power and purpose of abstract content on its own terms; a feeling that ‘painting about painting’, and paint as paint is not enough.

Of course it’s not enough, but that’s no reason to back off. The Abstract Expressionists were notoriously loath to abandon subject-matter and metaphor; and looking at Pollock’s late painting and his return to figuration, recently reviewed here by John Bunker on Abcrit, you get the strong impression that, very different from Gear though he was, he too fretted about abstraction’s detachment from human content. Pushing on beyond this point, keeping faith with the abstract, believing in its power, remains to this day a radical and tough thing to do… as we continue to see.

…………………………………….

Tucked away in the nether regions of Greenwich, in three separated spaces, is Greenwich University’s Stockwell Depot 1967 – 1979, a well researched, catalogued and curated exhibition by the former editor of abstractcritical, Sam Cornish. He has collected together works by some of the artists who occupied the eponymous studios and organised and participated in exhibitions there during the late sixties and seventies. This covers a period when abstract painting and sculpture had slipped from pole position at the cutting-edge of art practice, and were being increasingly eclipsed by all manner of anti-object and performance art. Indeed, Stockwell itself, one of the first artist-organised studio complexes, was begun more as an outpost to the experimental wing of St. Martin’s School of Art sculpture department than the focus for welded steel sculpture that came to later define it. Cornish’s recreation of Deep Space Installation, 1970, by Roland Brenner, reflects the adoption by some of the artists who founded Stockwell of the conceptualisation and dematerialisation of sculpture which had by then come to monopolize the discourse in the art magazines and the commercial and public galleries of the time (Harald Szeemann’s When Attitudes Become Form was the seminal ICA show in 1969). In its turn, that particular line of work had disappeared from Stockwell Depot by the early seventies, by way of the departure of some of the founder members, and the building was taken over mainly by abstract steel sculptors: Peter Hide, John Foster, Katherine Gili, Anthony Smart, David Evison. Also in the building, or taking part in exhibitions there, were a number of abstract painters following in the wake of, and reacting to, American Abstract Expressionism and Post-Painterly Abstraction: John McLean, Fred Pollock, Jennifer Durrant, Geoff Rigden, Douglas Abercrombie, Alan Gouk, Stephanie Bergman, Geoff Hollow amongst them. These artists form the main focus of the Greenwich exhibition. (The full story of Stockwell is well told in the exhibition catalogue.)

What is interesting is to note the unconventionality of the best of the later seventies works from Stockwell, and how, through a clear sense of physicality and spatiality, they put themselves beyond the aesthetic structuring of much other abstract work of that time, which though striving for novelty was visually more predictable and passive. This contradicts the perception, then and now – for it persists – that the Stockwell Depot work was orthodox. The sculpture in particular was viewed by the artworld as an academic follow-on to St. Martin’s, in the shadow of Caro, and it became marginalised as such. A more perceptive view reveals it to be no such thing; the Stockwell sculptors were breaking free from Caro’s influence and developing ways to reinvent sculptural structures, free of Caro’s predilection for pictorial solutions to sculptural propositions. The sculptures of Anthony Smart and John Foster in particular had by the late seventies completely broken from anything remotely allied to Caro’s frontality, or from the New Generation’s often glib sculpture-by-design, or from any trace of American minimalism. This was a real and measured progress in sculpture, towards a fuller three-dimensionality, confident in the strength of its articulated abstract-ness. Even now, in the midst of a resurgence of interest in abstract painting, it is unlikely the work in this exhibition will get the attention it deserves, yet any direct comparison with the Contemporary abstract art that today receives plaudits will confirm that the bold and lucid organizations of, for example, Gouk’s Sea Horse Tenacity 1, Foster’s Three Cornered, or Smart’s Tamarind 5, are superior still.1 And whilst I’m in this territory, just look at how much more active, three-dimensional and downright sculptural Foster’s use of I-beams in Three Cornered is, compared to anything Caro ever did with them. We are in the midst of a Caro-fest at the moment, and I have no wish to denigrate him, but we have yet to get to grips, even here on Abcrit, with just how far abstract sculpture has moved on from his approach – and, for that matter, from Foster too. It is a topic we must return to soon.

…………………………………….

Hans Hofmann: Catalogue Raisonné of Paintings is just recently published in the UK by Lund Humphries. These three volumes surprisingly reveal that, starting as early as 1949, Hofmann was engaged in making spontaneous and unformatted small abstract paintings running concurrently with his larger, more familiar canvasses. The latter were often based upon drawn images up until about 1950, and then came the rectangular slabs over loose brushwork with which we are accustomed. By contrast, these smaller works have very little drawing or orthogonal compositional devices, and range far and wide in an uninhibited manner, mixing splurged and freely brushed or splattered colour in a startling number of ways and with a multiplying range of results. This exciting experimentation had started to happen before the signature inclusion of rectangles in Hofmann’s work had begun in earnest, and it continued right up to the end of his career. Indeed, included at the end of the Catalogue Raisonné are almost a hundred works described as ‘palette paintings’, which differ from the small spontaneous paintings to which I refer only by being unsigned or un-annotated variations of them. These experimental works seem to me suddenly of more interest than the Hofmanns with which we are familiar.2

The totality of all of these unformatted works, signed or otherwise, and now fifty or sixty years old, amounts to a huge range of new content previously unseen, which is very ‘live’, very fresh, very ‘now’. Hofmann in the fifties and sixties was exploring options for abstract painting in an unrestrained manner that went far beyond anything Gear could ever imagine or participate in. It would be good to see an exhibition of this other side to Hofmann, (most of these works appear to still reside in the estate of the artist’s executors) so that we can better judge its value. It may well have something relevant to offer in the quest to get beyond what feels to me, still, like unnecessary restrictions on abstract art, a lack of faith in its ability to tap into what John Bunker has described as ‘a deeper sense of “us”’. Even with Hofmann, I sense there is a little holding back, a playing safe with familiar compositional arrangements, a reliance on allusiveness to figurative suggestions, sometimes a semi-figuration. Even he, one feels, could not quite go all the way in making meaningful abstract content blaze out of the work, without hindrance. There is still work to be done to liberate the ‘now’ in contemporaneity.

- The latter two sculptures are not in this show, but there are other works by these artists. Gouk’s Sea Horse Tenacity 1 and Foster’s Three Cornered are reproduced in the catalogue.

- I cannot find any available reproductions of these Hofmann works, other than in the book itself.

The curious case of William Gear, I found myself looking at a bunch of his drawings a while ago, a gallery out home had a truckload. There was freedom and play which just didn’t seem to make it to canvas, I can well imagine the dismissing of the drip and countless other techniques tried on paper but insisted on being brushed/knifed onto canvas ‘properly’.

He was by all accounts quite well acquainted with the European scene as much as the American but it doesn’t seemed to have gelled in the same way as with Davie for example – more a sense of roads not traveled with Gear.

However, I wouldn’t group him with Hilton, Lanyon etc…at all, that just seems a typical piece of easy categorisation; english + abstract = St Ives. I have been getting back into post war Germans of late, particularly Winter, Hartung, Uhlmann and along with the earnest heaviness of Cobra on those earlier Gears there seems more in common with Europe, certainly in the drawings with Nay’s colour and plenty of Klee too; structures and the black ‘skeletal’ graphic.

These forgotten figures pop up in the midst of the ‘contemporary’ seeming to prefigure trends, but really highlighting a lack of contemporary subject knowledge more than anything – historians/curators/journalists recycle the same figures so. The ‘Broken Yellow’ put me in mind of Phillip Taafe, I think we can lay the blame for the vogue for acrylic webs and networks at the door of Terry Winters. Saying that, a show of Bernard Cohen springs to mind, but his influence would not have made it across to Williamsburg and back.

The putting of ‘abstract’ objects into the garden seems a very English impulse, maybe Penrose? The line from surrealism through Moore lifting out bits of Tanguy, Nash to the current obsession with the stately home sculpture park. Certainly Capability Brown is a terrible setting for most metal, if Gear had suddenly picked up a torch and knocked up that gothic tank trap and put it above the HaHa instead of painting it that would not have been ‘forgotten’.

http://www.fossegallery.com/artistsdetails.php?name=William%20Gear

LikeLike

I think the art schools have a lot to answer for today. I’m not familiar with the course structuring at St Martins or any other art school in the U.K, but in Australia (where I reside), the art departments have been utterly consumed by the university model. One of the first things I noticed when I arrived at art school, was how everyone referred to their art making as their “practice”, as if you can clearly differentiate it from the rest of your life! It sounds like a legal practice, or a medical practice, as though you go to work, get paid and one day retire. It’s careerist infiltration it is. The other annoying thing about the art schools is that they bombard you with “contemporary” art and completely fail to inform students about any of the great art of yesteryear. It’s completely absurd and unique to art education. Even film school, which is so industry directed, would not for one moment dare to put students through a course without showing them a few of the classics. This unfortunate trend toward contemporaneity lends itself very particularly toward fine art.

I was thinking about why many lecturers limit themselves to showing and talking solely about contemporary art. I find the position to be cynical in the extreme. “We are going to show you what contemporary art looks like, so that you know how to position yourself within that framework, and forge a career for yourself.” This is university mindset. Business mindset. It seeps into every corner of what should be a pursuit based on what is artistically important, not financially so.

Abstract art always seems to get a pretty raw deal. If you think Britain ought to pay it more attention, try living in Australia. There are people here still bickering about the Whitlam government purchasing Jackson Pollock’s ‘Blue Poles’ in 1973. And if you told them that the Pollock is less abstract than a Tintoretto they’d think you mad. But whilst art schools may have at least moved on from the Blue Poles debate (though only slightly), when it comes to abstraction, there are only ever a handful of names that emerge and they’ll come as no surprise. Malevich, Kandinsky, Mondrian, Newman and of course, Pollock.

I reckon I can safely say that there is no one within an Australian art school talking about William Gear, but there are certainly a helluva lot of triangles floating about. I find it amusing to think that anyone currently painting them has been beaten to the post by a curmudgeon.

LikeLike

To large extent I would have to agree Harry, however, it’s something which has been foisted upon the art school system, a financing system based on employment outcomes and research incomes. I remember well as our college was dismantled around us in the late 80’s, but we can quickly become a bunch of nostalgic old men chuntering away here – I would equally be disturbed by cohorts of teenage creatives running to 50’s abstraction en masse!

There can’t be anything ‘wrong’ with cages of triangles any more than any other form, but surely the problem sits around voguishness/fashion, lack of informed practice/criticism, the ‘market’ etc…

It is with positioning historically uninformed formal reiteration as a contemporary ‘Avant Garde’ which surely grates.

Connecting with a couple of the previous articles here ‘#11 Real Painting’ and ‘#8 New Pictorial Economy’ it’s good ol’ Barney Newman and his aesthetic birdwatching.

Does the text seek to support the phenomena of the art object before us or does the object before us merely serve as a signpost to a research paper rendering it at best illustrative?

What’s in the work – What’s out of it?

If you want to ‘reference’ network theory then paint networks, simple.

In the contemporary environment driven by reference to text based data rather than studio discussion around ‘the doing’ – openness and play cannot be quantified, difficulty is a difficult sell. Complexity is difficult. The ‘hard won’ takes time and the world doesn’t have much patience anymore.

A young artist seeking a tutorial responded to my question ‘so what do you want from these objects?’ with ‘I want it to look like art!’ I didn’t expect that, ha, but I understand it.

It’s a very different place out there financially, nobody wants to starve in a garret and ‘authenticity’ means diddly squat, all of which have aspects which pain me.

For my own sanity, I’d rather run on ‘optimism of the will’ at present and take heart that sites like this, it’s archived predecessor and spinoff Brancaster Chronicles maintain and build a level of discourse around art making which challenge the given ‘contemporaneity’ around us.

Now Frei Otto, he new about cages of triangles.

LikeLiked by 1 person

With respect, Andrew, I think there is something ‘wrong’ with cages of triangles – quite a few things, actually, but not least it’s redundancy. OK, not ‘wrong’, but useless in any kind of real adventure into new abstract territory. Which is my point – don’t do redundant stuff, and especially don’t do it if it’s been done before. Not only do something that’s NEVER been done before, but do something that NO-ONE ELSE can do. Even if it doesn’t work out, it’s better than this:

http://www.theartnewspaper.com/news/news/158389/

LikeLike

Ha, I admit I was attempting to be positive, I sensed I was about to dive into a ‘its all gone to hell in a handcart’ which may have ruined my day. Harry’s observations of art school could easily have tipped over the edge and I had to shore my self up.

There is nothing ‘wrong’ with those networks, but that is semantic it certainly is a redundant device along with mush else en vogue.

One must be able to ‘fail’ to obtain authentic adventure and although I’m happy with that after all sorts of missteps and dead ends convincing others of the validity fighting for the right to fail is another matter.

However, I’m here to be cured of any institutionalised pragmatism which I have let temper my will. I was happy to escape my Dalston workspace with the sight of an ‘adult’ in pink fur one piece on Ridley Road. The zeitgeist indeed.

Unlikely I shall run into a copyright problem though, I’ve spent too long perfecting my rust recipe and experience tells me if ain’t shiny no-ones buying. I have a particular dislike of curly pointy ‘uplifting’ corporate stainless gee-gaws – Pheonixes for industrial parks. The brass neck of the developer is something. Kapoor’s bean was a beautifully made thing, but I lost interest in spectacle long ago along with slides and glowing sun installations.

LikeLike

My apologies Andrew. At the risk of ruining your day, I thought I might add that I agree that the art schools are not entirely to blame. The model has indeed been imposed upon them. But what I can’t quite reconcile myself with is that there are people working within these institutions who have a lot of power over impressionable minds, who call themselves artists and yet simply fail to expose students to great visual art unless they can find some way of tying it to some sort of social question. What I find even more unsettling, is that so many artists, both within the institution and outside of it, actually seem to like all this “contemporary” art. It could be because it legitimises their own poor offerings, and it could also be because they haven’t ever thought about it in relation to the great art that they’ve never really looked at. And I too am equally disturbed by the proliferation of young artists painting abstract 50s knock offs.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think you have nailed that, Harry: ‘It could be because it legitimises their own poor offerings’. The crap is self-perpetuating. The system was mostly like that in my time at art school, except that back then it was amateur, now it is fully monetised.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m curious, Robin, if you’d be willing to compare the work by Gouk directly to those by Gear? While you’re attention to the Gouk is more in passing, I get the sense that you find it superior to the works by Gear. While I admit, “Broken Yellow” does little or nothing for me, I find that in general, Gear’s work seems to establish a significantly more complex “space” and the relationships entailed therein. The Gouk is frankly a formless accretion of gestures that appears to have been “stopped” rather than resolved.

I get the sense that Gouk’s ‘seahorse’ is the form of abstract painting that closely fits you definition of “abstract” and thus is appeals to your bias, and yet I see it as significantly less complex than say “Composition”. All of which I find interesting given your repeatedly professed dislike of minimalist painting. While the myriad gestures in Gouk’s “Sea Horse Tenacity” create the illusion of complexity, in terms of decision making, its about as minimal as one gets.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yep, Harry, it tips me into despair because it resonates so acutely.

It is self-perpetuating within the ‘education’ system because it has been thoroughly corporatised – it has long been monetised. The ‘face palm’ moments are legion.

There was something to be said for a certain amateurism; expectations have changed from getting out, getting a studio and getting on with the work to legitimising work in often flimsy critical discourse and then placing into a ready art market niche – commodity manufacture in the guise of professionalism.

It’s broken and it is globally broken. The only positive is that around it’s edges the fallout is prompting glimpses of reaction.

The simultaneity and levelling of a google image search destroys a historical timeline, this is the research tool of choice, but without the guiding hand of someone with a depth of subject knowledge there is no-one to differentiate between welded fish ornament and a Smith.

Those dedicated guiding hands have long since been sacked and replaced with an iMac lounge.

However, the Gear show looks interesting, my previous knowledge was vague and after being intrigued by the drawings among the Cotswolds he is turning out to be a very interesting character.

More of such can only help with the despair, Harry.

I did get to see some of the Stockwell show, Robin, I will have to get hold of Sam Cornish’s book. It has brought into focus some things said at your Brancaster discussion, which I am still digesting.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I do like your questions, Alan. What on earth makes you think I’m biased?

Leaving that aside for the moment; yes, I do think the Gouk is better than any Gears that I have seen (which is quite a few recently). There are a number of issues here, and I need to separate them out a bit.

The complexity thing; complexity is not an aim, so there would be no point in attempting to “create the illusion of complexity”. Complexity for its own sake would be mere distracting complication. The aim has to be a lucid and resonant simplicity, a wholeness, but one which repays repeated visits with new aspects to that wholeness; which in my opinion can only come about through taking on complexity in all sorts of ways, and working through it. If you start with banality, you end up with banality (minimalism).

I do think Gear’s ‘Composition’, in its redundancy, is well on the way to banal. I certainly don’t think the Gouk is minimal, but I could be critical of that too. For example, the blue is a little too overwhelming and flattening, perhaps… However, the “myriad” gestures, for me, do add up to a whole thing, even if that whole thing is somewhat assisted by the all-over-ness of the blue, holding everything together.

There is a bigger issue here, though, and it is to do with the thing I have tried to address throughout this essay – abstract content. As I have indicated, Gear is for the most part not really very abstract at all. The “complex space” you appear to see in his work is something I don’t really find; I think they are mostly rather flat and diminished depictions of figurative space in a straightjacket of formalist composition. “Autumn Landscape” is seriously conflicted as to what it is trying to do – depict “things” in space, floating about? It’s very unreal, very clunky, without any spatial credibility. The Gouk is free of that, on the whole and has some space and life to it, as well as the spontaneity that is so absent from the Gears… but maybe not entirely, because it comes hot on the heels of the more process-orientated American painting of its time and has perhaps not quite escaped the literalism of that manner of spontaneous interaction with the work. Maybe.

I’m certainly not suggesting anyone should paint like this now. But yes, the Gouk is better than the Gears and better than a very large percentage of contemporary painting.

LikeLike

Some more Gear/Gouk thoughts.

That very ‘flatness’ – the ironing out of immediacy in ‘Broken Yellow’ is what I mean by the gesture and play evident in some of the drawings not carrying over into the paintings, this is of course common in drawings compared to subsequent painting or sculpture output.

Yet as a painter engaged with abstraction as a subject within a climate of (largely) gestural abstraction it seems a backward step, a tidying up. Similarly the insistence on partial filling of the ground to the edge in the other images rather than, for instance raw canvas when many of the drawn events utilise the freedom of the raw paper space. That object in landscape quality will always undermine any sense of ‘all overness’ even if you cut it up a vestige will remain.

The sliced and diced collage quality of ‘Broken Yellow’ gives an apparent ‘complexity’ in composition, but actually in the end a decorative evenness hence Phillip Taafe (maybe a stretch, but we were talking prefiguring earlier!) it is as though he dissects a strong central motif which may have seemed too obvious at the time. I could indeed, imagine it recently made, cut/rearranged/merged in Photoshop.

I get the sense from Gear of knowledge and eye for the international scene around him, beyond the UK/St Ives etc… but who could not perhaps leave his training behind, unlike Davie for example. Davie often said he preferred paper, less precious about it, but we are also told he would cover or erase seemingly finished areas ruthlessly on canvas too.

Apparent complexity seems there in the Gear in the first instance compared to the seeming confusion of the Gouk, but there is greater variety of ‘phenomena’ in/on the Gouk, I don’t particularly ‘like’ either, however, I am far more challenged by ‘muck’ and ‘movement’ of the more gestural and subsequently able to sustain longer investigation of it.

I am not terribly up to speed on paint varieties as substance, but on seeing the ‘Seahorse Tenacity’ in Greenwich has it perhaps dulled over time? How, important does that initial ‘fresh’ paint surface seem important to such abstraction – I of course did not see it before this current Stockwell show, but I would interested if any of the painters on here have a thought on such if at all relevant.

LikeLike

‘don’t do redundant stuff, and especially don’t do it if it’s been done before. Not only do something that’s NEVER been done before, but do something that NO-ONE ELSE can do’ – that’s clearly ridiculous Robin – how can a prime form such as a triangle be redundant? – you’ll be saying space or light is redundant next! I do agree that certain well trodden paths can become over-used or too easy to follow, but the crucial thing is motive – where you’re coming from as a painter. If you find yourself returning to some universal form – old as the hills – as so many others have done, nothing wrong with that, so long as you find it genuinely of interest. And the point is that you are going to explore ‘that old thing’ in your way, which can certainly be new and fresh (show me two triangles that are exactly the same in the paintings you speak of). I remember well certain students at art school pursuing a course of action simply because no-one else had done it – trying to become the latest fashion – no genuine exploration in it at all (down the Warhol path?) – I can’t imagine that is what you’re advocating – novelty. And I quite agree with Alan Pocaro regarding Gouk and Gear. Enjoy the Agnes Martin show Robin??

LikeLike

I stand by my comments – invent new stuff. My rather brief thoughts on the Agnes Martin are posted after Charley Peters’ review on this site. Stripes are worse than triangles.

LikeLike

I wouldn’t ban the triangle as it’s a rather nice shape. However, it is not a profound shape, unless perhaps you are a mathematician or unless it offers some kind of profound spiritual meaning for you. If it does the latter you need to get out more.

When artists get caught up in repetitive shapes it really isn’t ‘visually’ interesting surely? Patterns can be nIce in terms of decor of course.

What is visually ambitious? What might be adventurous visually? It’s tough isn’t it as we have so much wealth of visual experience? What can we do that is in anyway ‘new’?

While I don’t quite see the same value in terms such as originality, objectivity, as Robin, I think I share a questioning of the value, worth, of painting and sculpture, and a suspician of shoehorned in theory, concepts, philosophy, biographical info (nice bloke does not equal good painter), stuff which tries to justify work that is often lazy or dull.

And being someone who greatly values a philosophical approach to life I too try to see beyond the visual quality and value of a work of visual art, to try and make sense of its wider meaning. However, I am afraid its all rather limited.

I can see the importance of my philosophy in my creative process. But when it comes to judging the quality of my work this philosophy and process is almost entirely redundant. This, in fact, is quite political because I can’t justify its value from external ‘stuff’, the value is up to each and every viewer.

LikeLike

I reckon we can draw a line under the triangle in art. John’s right, it is a nice shape. I seem to recall it being my favourite shape as a kid, but I don’t think I ever felt inclined to draw it over and over again. But though it can be nice, as a thing in and of itself, it has no inherent value. One of the problems with how it is used in paintings is that it is always so isolated, so recognisable. We just see it for what it is and give it a name, “a triangle”. This seems to go against what I would think to be one of the most important aims of abstract art, escaping reference.

Now if we look at say, Cezanne’s “View of Auvers” 1873 (link below), we might almost be able to spot quite a few triangles nestled away in the forms of rooftops and walls.

http://www.wikiart.org/en/paul-cezanne/view-of-auvers-1873

But they’re not really triangles are they? They are so thoroughly integrated into the rest of the workings of the painting. I don’t think I could definitively say that the triangles of the rooftops are a distinctly separate form from the green surrounds, all the way up to the sky.

Compare this to “Intersections” by Helen Eager, an Australian artist who seems to be getting a bit of attention at the moment.

http://www.utopiaartsydney.com.au/ex-works-alt.php?exhibitionID=95

Now sure, someone could argue that the triangles are integrated into the other shapes in the picture and combine to form some other shape that isn’t just a triangle. But those triangles are all I can see! I know I’ve chosen some pretty average paintings to pair up against the Cezanne, but I just think that triangles cannot ever be abstract until they are comprehensively incorporated into everything else that may make up the picture, and by that point they’re not even triangles anymore are they?

I don’t think triangles in art are as old as the hills. I think they’re no older than Modernism really, when it started to become ok to make a simple shape that bears no relationship to anything around it. If we start to think that our own differing life experiences could potentially allow us to each bring something nuanced to a shape, then we’re kind of treating the triangle as our subject matter, and that seems a rather odd preoccupation for abstract art.

LikeLiked by 1 person

“treating the triangle as our subject matter, and that seems a rather odd preoccupation for abstract art.”

Indeed. While I’m sure you could do some interesting work limiting yourself to a few different types of shapes, you would probably have to rely on constrasting sizes, colours, etc, in a non repeating arrangement to provide a stimulating and absorbing content, and meaning, filled experience.

And your right, as the whole point, and strengths, of abstraction, seems to be what can follow from its non-referential content, which has everything to do with freedom, invention, and possibility.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Is it worth considering Gloria Petyarre’s approach (also represented by Utopia Arts Sydney) in connection with this discussion?.….i.e.

http://www.utopiaartsydney.com.au/enlarge_works.php?workID=489&artistID=6

LikeLike

Well, it might be, if you were to explain…

LikeLike

Hello Robin

Yes, I’ll attempt to explain in a little more detail.

Firstly, its been interesting to read an opinion from down under and, for me, a strange coincidence as I’m currently reading and researching indigenous Australian culture. I was struck that Harry considered abstract art to be ‘Western European’. Some time ago now when this site was Abstract Critical I briefly mentioned Emily Kame Kngwarreye in relation to a review of an exhibition of work by Yayoi Kusama; I suggested Emily was the finer artist. Both artists, of course, make extensive use of repetitive mark-making, particularly dots, but Emily does so in a way that is meaningful. It is meaning that is at the root of many of the problems encountered in contemporary visual art in Western Europe and, by historical association, North America.

I highlighted an example of work by Gloria Petyarre in relation to your argument on complexity where you state “complexity for its own sake would be mere distracting complication. The aim has to be a lucid and resonant simplicity, a wholeness, but one which repays repeated visits with new aspects to that wholeness; which in my opinion can only come about through taking on complexity in all sorts of ways, and working through it.’

This statement is of real value and in my opinion Gloria’s work is an example of ‘resonant simplicity’ where ‘complexity’ (i.e. the complexity of natural phenomena observed by the artist) is taken on and worked through in the art work via the repetition of a simple idiom, the ovoid. It is rewarding to look at even, sin of sins, via Google which is currently our only option here in the UK.

Contributors also stated the following:-

But though it [a triangle] can be nice, as a thing in and of itself, it has no inherent value. One of the problems with how it is used in paintings is that it is always so isolated, so recognizable. We just see it for what it is and give it a name, “a triangle”. This seems to go against what I would think to be one of the most important aims of abstract art, escaping reference.*

When artists get caught up in repetitive shapes it really isn’t ‘visually’ interesting surely? Patterns can be nice in terms of decor of course.

If we consider non-Western European forms of abstract art they do not escape reference – they embody reference. Attempts to escape reference in abstract art run the risk of a loss of meaning, rendering the work meaningless and of little or no real value to the viewer. In such cases the abstract work becomes an indulgence, a work only the artist him or herself ‘gets’. This indulgence can lead to isolation from society and introduces the problem of elitism. This ties in with the next comment highlighted, a common fear amongst many abstract art practitioners, the fear of decoration and the pleasure principle. Here again the problem is meaning. In much Western European thought (abstract) art that is decorative somehow lacks meaning – the decorative is shallow. Rather than appreciating the decorative as a way for the viewer to access art, retaining and combining the decorative with the serious (as is the case in the culture of indigenous Australia, for example) we have tended recently in the West to separate the two again creating division and propagating elitism.

Another point raised in the discussion was criticism of art tutors who fail to introduce their students to works of art of historical significance. This may indeed be true but in many cases it could simply be due to a lack of access. Kngwarreye’s work, for example, is rarely shown in this country which, as I understand the situation, is not the case in America where she and her kinsfolk enjoy great respect and appreciation.

*Here I’ve amended the contributions slightly for clarity.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Interesting, Tania – but it depends what you mean by ‘meaning’ (sorry).

It seems to me (and correct me if I am wrong) that your ‘meaningfulness’ relies upon an abstraction of things in the real world, outside of the work itself. My ‘meaningfulness’ relies upon things I can see happening in the work,that have no outside reference, that are complex but resolved, visually and abstractly.

It’s true I haven’t seen her work for real, but in reproduction Gloria Petyarre’s work looks to be repetitive and rather boring – a swirling pattern of marks. Do I have to know the back-story to get the meaning?

You say: “Attempts to escape reference in abstract art run the risk of a loss of meaning, rendering the work meaningless…” I just can’t agree with that. In fact, I think the opposite – that abstract visual things are very meaningful when they are part of, and form the whole of, a coherent work of abstract art. True and meaningful abstract content does not for me rely upon narrative, association, literal or literary allusion, metaphor, etc.; and whilst it’s true a lot of abstract (and abstracted) art is indulgent, boring and meaningless, so too is a lot of figurative art.

I would also be wary of denigrating too easily what is ‘decorative’, since, for an obvious example, Matisse is often so described, and there is nothing wrong with visual art looking good. Whether an artist is ‘decorative’ or not might depend upon their sensibility and is not necessarily a reflection of their quality.

There are also any number of decorative textiles and works of ‘applied art’, both traditional and modern (many better, in my opinion, than Gloria Petyarre), that are fantastic and wonderful to look at, without caring or knowing anything about context – and that very ‘wonderful-ness’ in the looking is very meaningful to me. Is that elitist? Well, it may set me apart from some people who don’t get excited by things on such a directly visual level, but what I see is there for everyone else to see too, if they so wish. That’s the great thing about abstract-ness, it’s all very open, and we can all get at the ‘meaning’ without being ‘in the know’ about the artist or their storyline. That’s not to say that we will or can spontaneously ‘get it’ every time, and there is always much to think about, consider and discuss; and, of course, lots of new things to discover…

But each to his or her own… I was talking with Ken Carpenter (another contributor to Abcrit) recently and we agreed to differ about what constitutes ‘abstract content’. For him, it was very much to do with the motivation of the artist which broadened out the human content of the work (similar perhaps to your position); for me, it is just the nitty-gritty of the stuff in front of my nose and how it all locks together and does its stuff in a manner that I can marvel at.

LikeLike

Hi there Robin

What is meaning?! Well, that’s a subject and a half….No, course I don’t mean abstract art must necessarily reference things in the real world to be of value and of course ‘meaning’ can and should be delivered through the quality of an individual work, be it painting or sculpture.

Its a pity you don’t respond positively to Gloria’s work but your comments touch on a different debate – simplicity as elegance and refinement or simplicity as paucity of content. Here we’re probably also wandering into the realm of subjective responses and clearly this type of abstract work doesn’t do it for you.

When I discuss abstract art with ‘the man in the street’, i.e. those not working with abstract art day-in-day-out, they often don’t know how to respond to it, finding it alien and of little relevance to their lives which is why I cautioned that arguing for a complete escape from reference in abstract art runs the risk of rendering the work meaningless to the viewer. At least we agree on the fact that the decorative does have a valid role to play and its great to read that you feel there is nothing wrong with visual art ‘looking good’. Actually there are a great many contemporary visual artists who do have a problem with visual art ‘looking good’ – another area for discussion. However, when you write that what you see is there for everyone else to see I’m afraid, on a practical level, this simply isn’t the case. Most abstract art is shown in London, though some regional exhibitions happen now and then and the abstract art that is shown in London seems to be selective. Last weekend I managed to see Olga de Amaral at Rook and Raven and going through the information it appears her work is not held in any British collection at all and this is only the second time her work has been exhibited in the UK – and she’s over eighty! The problem of what is and isn’t exhibited here brings us back to the point I made in my original comment with regard to access. Unfortunately this site has been slimmed down a great deal and readers lost the excellent exhibition guide. The old AbCrit site also allowed for a greater diversity of work to be discussed. At least a version of the previous site has survived. Here the internet does play a positive role in widening access and generating interest in this area of contemporary visual art.

Finally, of course I agree that the abstract offers the viewer the option of a personal response and that discovery and adventure are positive aspects of abstract art. However, surely we need the folk to be on board the ship before it sets sail on all of those adventures…..

LikeLike

Hi Tania,

I don’t think I really need to add much to anything Robin said about abstract art being meaningful without reference. He’s put it better than I ever could, and better still in his essay on the old abstract critical site, “What’s Abstract About Art?”. I think Carl Kandutch’s essays on Caro and Fried are highly relevant to this too, in how meaning can be extracted from a highly attentive focus on what is happening in a visual, abstract sense. Because there are reasons why non-referential abstract art and Modernism happened when they did, and the sky didn’t fall in. I wouldn’t worry about loss of reference leading to isolation from society. People worried that atheism would lead to a breakdown of law and order, but we’ve probably never been better behaved, at least in Western style democracy, which brings me to your other point.

I don’t know that I ever said specifically that abstract art is Western/European. I’m assuming that you gathered this from my frustration that Australia doesn’t really do abstract, and since you must think that Indigenous art is abstract, that I was therefore ignoring it. You may be right, and thanks for mentioning Emily Kame Kngwarreye. I’ve actually seen her work, while at art school no less, when she had an exhibition in the University gallery a few years ago. I really enjoyed it. It had colour and diversity and is definitely far more impressive than Kusama’s dots. However, I’ve got a couple of ideas about what abstract art means, and it kind of depends upon what sort of conversation is taking place. Firstly, there is the kind of abstract art that Robin talks about in “What’s abstract about art?” A visually meaningful experience, be it figurative or abstract. Secondly, the other definition of abstract is one that is intrinsically bound up in Modernism, and I don’t think that is a history that Australian Indigenous art is very much concerned with. I see no reason why it can’t engage with the former definition, but in painting at least, I think it is hard to work with repetitive pattern or a prescribed aesthetic, which Indigenous art has to a large extent, and expect to contribute something new and visually meaningful in the same sense that the kind of abstract art that interests me does.

Now I really don’t want to sound like I’m talking it down, because I actually see Indigenous art as an awesomely rich tradition, as diverse as it is old, thousands of years old. There are so many different cultures, each with their own aesthetic, but unfortunately, that diversity has sort of been swept up by westerners into a big pot, stirred around and boiled down to a pretty generic understanding of what is thousands of years worth of culture. This is very convenient for white people, who can bundle up these paintings, whack them on some cheap stretcher bars, hang them in a gallery and flog them for a pretty penny, to people who don’t seem to wonder about who actually gets that money. If the artists are getting it, good. The economic opportunities for Indigenous peoples in this country is a national disgrace. We’re happy to hang the paintings on the wall and applaud their efforts on the football field (sometimes), but talk about fixing issues around domestic violence, housing, child mortality and constitutional recognition and we just don’t want to go there.

But just looking at the paintings themselves, I don’t think it’s helpful to view them in the context of abstract art, which is a Modernist context. Because at the heart of it, that’s not what these paintings are about. It’s a tradition of a wholly different nature to Western painting, almost as removed from it as applied arts, music or literature, but like those disciplines, still delightful on its own unique terms. But the word “tradition” is important here, because “tradition” involves continuing to do things as they have always been done (acknowledging that things will inevitably alter over time). Western painting on the other hand… I wonder how much it really has to do with tradition at all, particularly if we look at Modernism, such a condensed period of change and innovation, for better or for worse.

Also, I don’t know how true this is, but in Australia, we are taught at school that a major part of Aboriginal art is about storytelling and mapping. If that is so then it is less abstract still, but takes on a whole lot of other fascinating meanings, ones for which I would have to have insider knowledge in order to appreciate.

LikeLike

This is worth reading for a subtle view on intentionality and meaningfulness: http://bombmagazine.org/article/044448/todd-cronan

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Harry

Firstly, thank you for responding and from such a distance. I will catch up on the recommended reading (including Robin’s suggestion).

Great to read you’ve experienced Emily’s work directly (I’ve only seen one of her pieces at the RA’s Australia exhibition, 2013) and that you agree re. Kusama. On the notion that the art of Aboriginal people is not intrinsically bound up with Modernism its worth reading ‘Perceptions of Aboriginal Art: A History’ by Philip Jones published in ‘Dreamings: The Art of Aboriginal Australia’ ed. Peter Sutton. The ‘birth’ of Modernism in Europe about 100 or so years ago now relied heavily on ‘alien’ cultures including that of the Aborigines. Seemingly Paul Klee reworked Arnham land bark painting imagery as well as ‘borrowing’ ideas from Inuit culture. Picasso famously reworked African imagery, Matisse used Polynesian sculptures for inspiration and ‘Modernism’ was influenced to an enormous extent by Japan. All of these cultures have in turn been influenced by European culture – its a symbiotic thing.

It is indisputable that Aboriginal culture is wholly different and all the more to be admired for that difference. However, it is also a dynamic, living culture. When the exhibition ‘Dreamings: The Art of Aboriginal Australia’ was shown in New York in 1988 it was an attempt to shift the perception of Aboriginal culture as being relevant only to museums of ethnography. It was a move to put it on a par with the European culture which it can, and obviously did, influence. I’m not sure I entirely agree with the suggestion that storytelling and mapping are somehow not part of abstract art here in Europe – which brings us back to reference and meaning again. If my memory serves me right Kandinsky’s paintings, for example, often depict (be it upside down) heroes from Russian folklore.

Actually I’m not concerned about a ‘loss of reference leading to isolation from society’. What I am concerned about is indifference and ignorance. When I discussed abstract art with non-art students, usually adamantly hostile to the subject, I would introduce Stonehenge as a way of illustrating the importance and integrity of abstract art within British culture. We don’t know, and in some ways hopefully we will never know, what Stonehenge is, what it stands for, what it means. It may reference the sun, the moon, the earth. It may be an exercise in complex geometry. Whatever its meaning is it is certainly abstract. Why abstract art was, and in some ways continues to be, sidelined in British culture is the real mystery.

LikeLike

Hi Tania,

A pleasure to chat, and think nothing of the distance.

Whilst indigenous cultures from all around the world were doubtlessly pivotal in influencing and broadening the aesthetics of Modernist artists, that still doesn’t make non-western art histories and cultures “Modernist”. And yes, whilst Western art has certainly left its own mark in turn upon indigenous arts from around the world, I think that is less to do with Modernism and more an inevitability of that other more irresistible phenomenon, globalisation. Aboriginal art (as a generalised notion) has certainly changed a lot since white settlement, and I’m not disputing its right to be exhibited in contemporary art galleries and outside of ethnographical museums. I merely don’t see it as abstract, but see no reason why someone who is Aboriginal cannot make abstract art. When you put up the link to Gloria Petyarre, I must admit I didn’t make the connection that she was Aboriginal. So I saw her work and continue to see it as fitting in to a rather broad definition of abstract painting (perhaps not my own definition, but how abstract painting is most generally viewed). Unfortunately I just didn’t like her painting. Emily’s work appeals to me much much more.

I’m also going to stand by my suggestion that storytelling is not abstract, and go so far as to say that an upside down figurative Kandinsky is not abstract either. But Kandinsky is also notorious for doing the things being discussed in this thread that hold abstract art back, and for those reasons I don’t really think of him as particularly abstract, but as an important Modernist figure who set the ball rolling in some sense, but simultaneously laid the groundwork for problems that still plague us today. For he was very prone to want to find something external to his paintings in order to find meaning in them, no matter how much he banged on about “inner necessity”. Music, spirituality and colours as symbols were his resorts. Apparently he turned to painting after seeing a work by Monet of some haystacks and realised that Monet wasn’t painting the haystacks at all, but was interested in painting itself. Well he’d be right, but I think Monet had more faith in painting than Kandinsky did, and that the latter must have gone on to completely misunderstand or forget what he was drawn to in Monet. Kandinsky was unable to keep the ego out.

I suppose my initial gripe was that abstract art isn’t really discussed adequately at art school, and that when it is brought up, it is invariably guys like Kandinsky who get talked about, because they offer an easy way in, in that the lecturers don’t actually have to talk about the work, because the artist has already willingly offered up a whole lot of other philosophical and political stuff to distract from that issue. The art that I see as being abstract doesn’t get a look in. I think the kind of abstract art I like is possibly more likely to be appreciated by the “uninitiated” and in my experience it is, because they don’t feel intimidated by not being “in the know” about the philosophical referencing and judgemental politics. The experience is akin to seeing a Monet.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Harry

Thank you for getting back in touch – Australia is so vast and far away but the internet seems to eliminate distance. Some questions:-

You prefer Emily’s work to Gloria’s – are you able to explain why or is it simply gut feeling?

You feel abstract art is being ‘held back’ – can you expand on this?

‘the problems that still plague us today’ – what are these problems and how do they affect current abstraction?

The Kandinsky issue – I’m not a Kandinsky scholar by any manner of means I simply offered Kandinsky as an example of how story-telling influenced the development of abstract art in the early 20th century. My point here, along with a quibble I have with the notion that mapping in some way is not ‘abstract art’, is that visual art, be it abstract or not, is influenced by and is a product of all cultural phenomenon considered to be external to it (Philip King’s essay is useful on this point). I have no idea about Kandinsky’s ego – but many artists are (unfortunately) egomaniacs…

I agree informed discussion of abstract art is often omitted from critical theory options in art school nowadays and I agreed with your earlier comment that ‘practice’ is an odd way of describing what visual artists do. It is also true that there is a great deal too much jargon in contemporary visual art, a point raised recently by Grayson Perry in his series of Reith lectures.

From your comment ‘the artist has already willingly offered up a whole lot of other philosophical and political stuff to distract from that issue (i.e. talking about the art work)’ I understand that you are interested in colour, form, space etc. i.e that you are interested in the ‘classical’ elements of visual art as opposed to what is now considered contemporary visual art i.e. work which forefronts social and political theories, contemporary philosophy etc. rather than visual quality – am I right here?

The art that you consider to be ‘abstract’ – is it possible you can offer a few examples?

I will re-read the whole thread and try and remember some of what my line of thinking was (!) in order to explain more fully why I introduced Gloria’s work into the discussion. At least this site offers an opportunity to discuss abstract art more fully post art-school which is a sort of progress.

All the best

Tania

LikeLike

Sure Tania,

But firstly, I’d be careful before bringing old Grayson into this… Have a read…

http://www.smh.com.au/entertainment/art-and-design/british-turner-prizewinning-artist-grayson-perry-questions-australian-aboriginal-painting-20151002-gjzpne.html

He goes a bit further than me. All I’m saying is that it isn’t abstract.

I prefer Emily’s work to those particular works of Gloria Petyarre’s you referred me to, because I find them to be less predictable, more spatial even, and I think that has something to do with the amount of colour she uses, as well as contrasting tones, with rather dramatic shifts between vibrant colour and dark blacks. Those works by Gloria were limited in colour and formulaic in application, working to a sort of system. They didn’t surprise me in any way. However, I now know that not all her work is like this, and I also appreciate that she and Emily have made paintings that can be viewed outside of a context of their respective makers’ indigenous roots. But you can still see the evidence of it (and both Emily and Gloria would probably want us to), in things like the dots and repetitive mark making. Perhaps that’s not a problem, it depends on your interests and ambitions. It is a problem if that is what you do, but your aims are directed towards “Abstract Art”. It’s the same as triangles. Something easy that you can pick out, like a face or a horizon line. Add to that… artist back story, cultural heritage, literal and physical processes, anything outside the inner workings of the work that people, artist included, can latch onto and treat as content and prevent us from really getting to what is going on in the work, if there is anything at all. Those are just a few of the easier things abstract art needs to get over, the problem goes much deeper than that. I think so much of it really comes down to egomania, and Modernism for bringing a different kind of artist to the table, the academic. Kandinsky personifies this.

As for my own way for appreciating abstract art, I don’t think I have any set of criteria that I tick off as I see it. I certainly never think of it as “classical”, because I don’t think there are any rules for how something can “work”. I put up a link to Cezanne earlier, but I don’t think he did anything by the book. The kind of abstract art I like is pretty much what gets discussed here on abcrit and Brancaster for that matter. But as to what I think should be discussed in art school, I’m not suggesting it should simply be what I like personally. I couldn’t possibly expect an Australian art school to conduct lectures on the Stockwell depot. I don’t know that an English one would either. But here, lecturers don’t even talk about Caro, Noland, Stella even! It’s not my favourite work, but I think that work ought to be discussed. But why talk about them when we’ve got Warhol? Hofmann I really like, and he certainly had a lot to say about his work, but I suppose “push pull theory” relates too much to what is actually happening in the pictures. Best to stick with Barney Newman and his sublime.

When we bring in external political, spiritual and philosophical stuff, we are talking about very un-abstract things. Things that are easier to talk about than the visual workings of a painting. We are probably more likely to want to discuss abstract visual elements in Cezanne or Monet, because why would we want to talk about haystacks? Cezanne and Monet leave the ego out of their work. The irony is that so much contemporary work, which theorises about political Western dominance, is actually perpetuating that problem and feeding off it, and playing up to the very thing that differentiates 20th century Western art form Eastern or non Western cultures… the ego. The idea that I’ve got something very important to say and everyone needs to hear it. Such an ambition isn’t found in traditional non-Western art.

I don’t think storytelling has anything to do with the origins of abstract art, other than in some perverse sense of wanting to get away from it. But then we’re embarking on a whole other discussion about context. All I’ll say is, yes, everything influences everything, but we’re underestimating people’s deliberate efforts if we just assume that it is all an inevitable product of cultural phenomenon. Not if people don’t react it ain’t! A friend of mine broke his neck falling down the stairs at my house the other night, but it’s not my fault for throwing a party. He took it upon himself to do something so outlandish and consequential (but don’t fret, he’s fine).

LikeLike

Hi Harry

Thank you for that – good old Grayson – seeking out publicity as usual and now he’s turning up in Australia stirring the pot (excuse the pun!). Its one of his performance strategies – a way to get everyone talking, mainly about him, but also about that old colonialism chestnut. Still, to be fair he is worth listening to if you can access his Reith lectures and really there is too much jargon in contemporary art, as there is in many areas of intellectual life including both science and philosophy. Many scientists would happily agree with this by the way.

I’ve just posted a comment in reply to Robin where I again cited a work by an indigenous Australian (its worryingly becoming a mission oh dear). I am trying to bring the discussion back to William Gear but appear to be taking the long route round. I will get around to re-reading the original article and subsequent discussion so I can reply to your latest comment fully. What a deal of reading AbCrit gets folk to do….

Best wishes

Tania

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hello Harry

Its been a while since I promised to get back to you (November last year!).

I’ve just been watching A History of Britain [ep. 3], available on BBC IPlayer at:-

http://www.bbc.co.uk/iplayer/episode/b00z0k23/a-history-of-ancient-britain-series-1-3-age-of-cosmology

which includes a brief survey of Ireland’s Neolithic heritage. Newgrange’s triple spiral and the abstract marks on the stones at Knowth Passage Tomb are fascinating evidence of how ancient and deep-seated the impulse to make abstract marks is. It reminded me too of our discussion on AbCrit re. Emily Kame Knwarreye, Gloria Petyarre etc. and your point about egomania; examples of indigenous art such as the Newgrange triple spiral obviously eliminate the issue as no-one knows who carved it and such information is irrelevant anyway.

If you’d like to continue the discussion let me know, otherwise no worries. Hope your friend made a full recovery…….

LikeLike

Hello Tania,

Time has certainly raced by. Thanks for the link. It sounds interesting. I’ll watch it and try to get back to you if I can.

And yes, the fellow with the bad neck is doing remarkably well.

Best.

LikeLike

Hi again Tania,

I’ve just tried to watch the video you recommended but the iplayer won’t let me because I’m not in the UK. Nevertheless, it is very intriguing, wondering about what could have motivated ancient peoples to build the things that they did, make the marks that they made. They could have been raging egotists, but we’ll never know. That’s the thing about really great art, or great abstract art. We don’t have to know anything about the life of the person who made it in order to enjoy it, or be moved by it. So in actual fact, I think that the most scandalously egotistical work comes from about the middle of the twentieth century onwards and tends to be figurative. As figurative art loses ground to abstract art in the innovation stakes, it realises that the only place it can go is deeper into itself, or into the depraved psyche of the artist. It retreats into a rank subjectivity, that is all about trying to impress people not with plastic and spatial innovation, but with sordid autobiographical details of the artist’s life. Take Bacon, Kippenberger (are there others with names that sound like food?). Nor does it have to be so buffoonish either. It can be subtle, cold and intelligent, like Richter or Kiefer, but equally pretentious and attention seeking.

This doesn’t mean that abstract art is immune to the ego. It has gotten in the way for certain figures in the past and it will continue to do so. But perhaps many of those ego-assuaging tendencies will occur outside of the work, which could be just as bad, but not as instantly vomit-inducing and cringeworthy.

Many people equate much of Abstract Expressionism with egomania but I think that’s grossly unfair. Painters then were trying to find ways of making new paintings, much like Monet was. They took it where it had to go in order to keep it alive. Some “Post Painterly Abstraction” could be seen to try to directly address the removal of the ego, in suppressing expressionistic flourishes and creating a kind of anonymity. Though perhaps that in itself is an expression of the ego, through a too self conscious attempt to regulate it. But I don’t want to go down the road of pigeon holing a generation of artists into these categories and attaching some sort of collective intention to them all. Who knows what they were really thinking?

This might all sound like a bit of a rant, though I think it does follow on somewhat from where we left off several months ago. If I can tie it back at all to your most recent comment, I would add that I’m not entirely sure about the “deep-seated impulse to create abstract art” and what that might mean. I know that I personally have that impulse, but it is an impulse that I learnt, if that makes sense. I suppose your point (correct me if I’m wrong) is that the intention behind something like Stonehenge does not have to be revealed in order for us to experience it as abstract? And so given that we don’t have that information (the initial intent), and that if you looked at Stonehenge purely objectively and without any reference to its historical context, it could conceivably pass as some sort of abstract sculpture? I must admit, I do not know and am not qualified to, having never been to Stonehenge.

But I do think that in the case of Aboriginal painting, it is very different to “Western Abstract Art”, and not just because it has been made explicitly clear to us that it is not it’s intention to be abstract as so much of the imagery has direct referential meanings, but also because it is quite unrelated to Western abstract painting on a visual level in my opinion.

I’ll just add regarding Stonehenge, that it might not be necessary for it to be “abstract” at all in order for it to be of interest to us, and that we run the risk of imposing our way of thinking about art onto things that just don’t require that mindset. It could well be abstract, but it just wouldn’t be of any use to an abstract sculptor today to take a cue from Stonehenge, would it?

Anyway, thanks for getting me thinking about this again, Tania. It’s an interesting one. Fairly murky too, because it’s about trying to get to grips with all the different things we take “abstract” to mean. Buggered if I know how William Gear sparked all this.

All the best,

Harry

LikeLike

This comment is in reply to Robin’s recommended text from Bomb magazine

Robin,

Thank you for posting the link to this article. A thought-provoking read. The point about a ‘risk-averse’ art world is interesting; political art does seem, in some ways, to be ‘non-political’. It would be difficult to imagine a contemporary art gallery staging work by an artist overtly committed to the politics of say, UKIP, for example. The provocatively political murals of Belfast rarely get acknowledged as ‘art’ and if nationalism were to be supported through the current art system it would more likely be ‘celtic’ (i.e. Scottish and Welsh) rather than English. Perhaps its worth considering the Italian Futurists – radical art, ugly politics. The critics’ point that the humanities today are ‘virtually defined by an emphatic commitment to not making claims about anything that could raise the level of dispute (that is, non-factual dispute)’ surely has some credibility.

Can their proposition ‘if we start with painting rather than with presumptions about its inability to do anything now, we might generate more interesting discussions about what’s going on in painting now’ be applied to ‘Yumari’ [1983, Uta Uta Jangala, Papunya, Central Australia. Acylic on canvas, 244 x 366 cm]? I’d like to think it could. Following a visit to an exhibition of paintings by a group of talented and committed painters in Bermondsey recently I went on to enjoy ‘Indigenous Australia – enduring civilisation’ at the British Museum where I saw ‘Yumari’, now considered a masterpiece. As indigenous Australians are famous for not having a material culture and seemingly did not develop ‘cities’ the use of ‘civilisation’* in the title indicates a step-change in understanding; a step-change which perhaps could be followed here.

‘Yumari’ and other examples of Aboriginal ‘painting’ are immediately recognizable as ‘meaningful’ in a way the paintings in Bermondsey are not. The artists involved in the production of both ‘Yumari’ and the work on show in Bermondsey all display ‘intention’ (if I understand the critics correctly on this which I may not), the settings in which the work was experienced i.e. deliberately constructed viewing spaces (‘galleries’) differed very little from one another (though the loos in the British Museum are much nicer) and all the work was created using paint on (mainly) canvas. In both cases the work complies to ‘suggestion’ rather than ‘description’ and all the work involved both figurative and abstract elements. Yet ‘Yumari’ remains unequivocally meaningful. Why? As a Westerner I could not possibly understand what ‘Yumari’ means. I don’t understand its references, its ‘dreaming’ story, its rules of composition (which are quite strictly laid down), its colour configuration. I don’t understand it but I, and many visitors to the exhibition, acknowledge the work as ‘meaningful’. Moreover ‘Yumari’ is not meaningful because the indigenous Australians are politically marginalized and bear witness to a history of social injustice. It is not ‘meaningful’ because of identity politics. Rather, it is meaningful because it is a visually powerful painting. It is first and foremost visual. The dominant sense in humans is vision (apologies for a ‘fact’) and this sense seeks out satisfaction. It is this truism which Matisse perhaps understood so well and which explains his long-standing admiration of Polynesian culture.

*A civilization (US) or civilisation (UK) is any complex society characterized by urban development, symbolic communication forms (typically, writing systems), and a perceived separation from and domination over the natural environment…(quick Wikipedia citation)

LikeLike

Hi Harry

Many thanks for getting in touch. What a shame BBC IPlayer doesn’t reach Australia – a missed opportunity for the Beeb there surely. And yes, how did William Gear transmute into Stonehenge!

I’ve re-read Robin’s original article and the various comments which it provoked and there was a logic, although it splits off along various tangents (with a great many triangles in the mix). I thought I’d go back to the beginning…..

Firstly a general point. William Gear’s painting ‘Autumn Landscape‘ won the Festival of Britain Purchase Prize in 1951. The Festival of Britain is an event of real significance in the popularization, and subsequent suppression, of ‘Modernism’ here in England. When it closed, most of the contents of the Festival were dismantled and, I understand, many were destroyed. Contemporary art historians would do well do analyze this action, its motives and certainly its legacy with regard to the (generally) lack lustre development of the visual arts here in the UK afterwards.

On Gear specifically, Robin argued that his paintings fail to address a ‘properly articulated abstract content [which] might carry real meaning of its own accord’. Robin compared weaknesses in Gear to strengths in Hofmann (specifically Hofmann’s works on paper). The issue of the triangle first emerged with Robin’s criticism of Gear’s ‘Composition’, 1949 which is described as a ‘loose scaffold of painted lines (triangles are favoured)’. According to Robin, Gear’s approach is quoted (though probably unconsciously) in much contemporary abstract painting today which is the poorer for it.