Hoyland, Caro, Noland at Pace Gallery, London.

In the mid-20th Century shared unreality that was ‘Caroland’ it was somehow viable, with intentions that were quite probably on the right side of honest, to make a sculpture – in this case, Stainless Piece C, 1974/5 – that sat flat on the floor and rose up no more than a couple of inches, so you looked down upon it like a relief laid horizontally (I made a few like this myself); and to make it out of a few scattered (or were they artfully composed?) pieces of stainless steel plate and other bits and pieces (David Smith’s steel?) that had been scoured with an angle-grinder to give an optical illusion of depth to its surface when it had none at all to its structure (again, like Smith?). In the Pace Gallery, London, this work is shown on a plinth that is a good three inches taller than the sculpture itself (didn’t Caro do away with plinths? Did the gallery decide the work’s lack of status required one?), making a combined height, sculpture and plinth, of oh… all of eight inches or so. And because it’s by Caro, and because he’s now dead (R.I.P.), and because it’s a piece of art history merchandising already, and because it’s the prestigious Pace Gallery; because of all this and more, and for no reason due to its inherent value, since it transparently has none, unless you view it through a thick haze of sentimental regret for simpler and more certain times in abstract art; this pathetic little piece of twaddle has become a luxury commodity, imbued with all the myths of modernism, reflecting back at us our own ‘good-housekeeping-modern-but-weren’t-we-ever-so-radical-back-in-the-sixties’ taste.

All the Caros in this show are poor; I would happily concede that he made quite a number of much better works than the ones here, thank goodness. Some of those better works were very positively and excitingly spatial, albeit perhaps in a rather architectural kind of way. However, pace (!) Kandutsch and Fried, here all the space and excitement has gone and we are left with the characteristics of a rather dull category of objecthood. Caro is riffing on tables, coffee and boardroom, and not very much else is occurring. Talk about ‘affective formalism’! Well, any little thing can affect a degree of something-or-other in the observer, can’t it? A thing that looks a bit like a table, because it’s a flat sheet laid out horizontally, a couple of feet off the floor, can generate feelings of, well… ‘tableness’, good heavens, and off we go. Think of all the associations with tables… and if that table-thing has what look like chairs-backs round it, and a sort of drawer, and is called Survey…; or if that table-thing has some curvy edges, and it’s called Bare…; well, the feelings just keep on coming, don’t they…? And then there is the feeling of how ‘right’ it all feels… if you own the taste! It gets to the point where you wonder what the purpose of all this ‘feeling’ in abstract art is for. I’m sure Caro wasn’t trying to con us, he was never that kind of bloke, and he really believed in the economy of these works as a step forward in modernism; but he shouldn’t have listened so attentively to his painter-friends, if, as seems likely, it was they who encouraged him to abandon what little remained by the seventies of his slender hold on three-dimensionality.

One of those painter-friends was Noland, and though it takes some doing to pull it off, the Nolands in this show are worse than the Caros. Of the three artists, Hoyland comes off by far the best. I don’t mean that his works here are, any of them, great paintings; but some of them are fair to middling good, at least for the period, if we are willing to go down that road of contextualising, albeit ever such a little way, with just a tad of that sentimental regret for those goddamn simpler and more certain times in abstract art. I’m certainly not willing or able to go too far down that way. Hoyland shows deftness and sensitivity to his materials and colours, and an ability to wring out from very simple means a little more than the sum of his parts; he has a bit of zip and aplomb. That still doesn’t add up to very much, even when it’s fifteen foot long, but at least it’s clever, and has some ambition, and makes Noland (on this showing) look a right klutz. Wow, are these Nolands boring – mechanically painted, dumb colour, pointless shapes; they have a sterility of surface that seems more akin to Pop than anything else. Nothing abstract happening here! Noland and Caro have both made much better works, but somehow the context at Pace means that’s not the point any more. From start to finish, artist to gallery, the whole thing is something of a conceit, based upon very little of substance.

Installation shot at Pace London, works by Hoyland. The work on the left is perhaps the best thing in the show.

I recall walking to the opening at Pace questioning why I was going there at all; why was I supporting an occasion all but consanguineous with the excesses of super-class consumerist wealth and taste displayed in the ignoble designer-palaces that line Bond Street? And the reason, of course, is that despite shortcomings in the work, I persist in believing in a glimmer of something real and adventurous in painting and sculpture from this supposedly seminal period of abstract art, something that even now I feel linked to, tenuously. Am I perhaps deluded? The thing is, despite all I have said, I still think the Hoylands are far better than most contemporary painting. That’s no great achievement, so I’m not even going to bother discussing more recent stuff that, rather than attempt to go somewhere new and more challenging, just bastardises these simplistic forms from fifty years ago.

I think at the heart of this is a paradox. At its most basic, abstract art (as opposed to ‘abstraction’) is about getting together some materials and working with them inventively until something emerges that makes some kind of visual sense. After that, it’s all about vision and ambition – how far are you going to go? So, on the one hand, the simplistic ‘going round in circles’ of a standard formalist approach leads to less and less being done with the material: yet at the same time, the processes to which the material becomes subjected to are brought more to the fore. As an example, we might easily imagine (if it’s not been done already) a modernist painter partially priming his/her canvas, only to decide that the ‘white-on-white’ was already looking good and was ‘enough’. So goes the stupidity (as I see it) of the Caro floor-based piece I originally described, where virtually nothing is done to the material other than to casually arrange it. There is nothing wrong with casually arranging things, but it’s just first base (if that). Such an abbreviation of methodology was intentional on the part of the artist, and was seen by commentators at the time (but perhaps no longer) as a radical and authentic visual statement which responded to the quiddity of making abstract steel sculpture; just as the hypothetical half-primed canvas too might be seen as a truth about painting.

Not so hypothetical, perhaps: http://www.nytimes.com/2015/12/11/arts/design/in-robert-ryman-one-color-with-the-power-of-many.html?_r=0 ).

Is this the democratisation of culture often referred to, such that everybody and anybody can get it, or even DIY-it? Or is it the exact opposite, the instant writing of art history in shallow gestures and big dollars, without the need to check on intrinsic value? Either way, are we anywhere near the endgame yet, please. I improbably found myself agreeing with director of Tate Modern Chris Dercon when, on the occasion of justifying the Turner Prize being given to worthy community architects Assemble, he was quoted as criticising the vulgarities of the contemporary art market thus: ‘The exponential increase in the financial importance of works of art has not been accompanied by a similar increase in their cultural significance. These are no longer cultural objects but fragments of a luxury-production.’ Quite so, Chris, quite so; and do you think perhaps that Tate Modern and the Turner Prize itself have done just a teensy-weensy little bit to further that particular financial model?

We hopefully no longer labour under the misconception (though some still do) that the kind of ‘less’ on show here at Pace is any kind of ‘more’, or have the conviction that that tired old maxim gives us leave as modern artists to do pretty much bugger-all with our materials before quitting on them, in the belief that they have gained some transcendent significance by our token interventions – à la Caro. But, if we have got past that blindness, we haven’t yet gone quite so far as to discover or invent sufficiently robust abstract content such that it will again and again absolutely compel us to take things a lot further. The means to gain such ends as we can now envision for abstract painting and sculpture will be simultaneously more exacting, and yet less to-the-fore, and at the service of the content of the work – if not indivisible from it. And please, let’s not hear it that spontaneity and impulsive expression (which are meaninglessly present in almost all of the work in this show, cool though it appears) are any kind of substitute for a discovered abstract content of substance – which, indeed, may or may not include both, alongside conscious intentionality and much else.

In other words, the hackneyed processes evident in the Pace Gallery work – all of it, from the laying-out horizontally of plates of unmanipulated steel, to the painting of stripes and rectangles in thin stains – need to be strongly interrogated by anyone who wants to move abstract art forward. The beguiling simplicity of this work does not bear scrutiny, and quickly turns on itself, becoming a presentational act of banality. This becomes particularly apparent when one considers works singly and separately from the context of the exhibition or series, when the incompleteness of the content of the individual works is exposed. This exhibition suggests that a wholeness based upon aesthetics, especially minimalist aesthetics, is unlikely to provide a fulfilling wholeness of content. The excitement of those initial breakthrough moments – of taking sculpture across the floor or staining colour into raw canvas – so very quickly become restrictive mannerisms, which in the end were the undoing of all three artists, who all got worse as their careers progressed. Who could find continuing interest in this work beyond a couple of minutes of looking (or a sustaining career, beyond a couple of years of making), other than someone who wants repeated confirmation of their own good taste? Those are, needless to say, just the people (the ones with money, anyhow) that Pace Gallery is targeting.

The paradox plays itself out as a truism: we know that all great art has lucidity. It seems spontaneous, effortless and direct, and therefore the way to make great abstract art must also be spontaneous, effortless and direct. Alas, that confuses the outcome with the process; combining an overarching simplicity with a depth of character in the content turns out to involve complexity, and entails far more than is offered by either a minimalist conceptual rigor mortis or an expressionist heart-on-sleeve outpouring. It involves engagement across a whole range of human capabilities; it probably involves making a mess of things from time to time too, when the complexity goes askew and refuses to be resolved. So what! – that risk is now a requirement. Placing plates horizontally, parallel to, or on the floor, like a table or a pavement, is not inherently risky or radical at all; painting parallel stripes or grids is not inherently risky or radical at all; these are sure-fire hits on low-level minimalist taste. That sort of thing is overrated, over-analysed, over-subscribed and… just over. We have passed beyond the cultural context that gave these token actions and forms any surprise or purchase. Yet much of the art world clings to this minimalist aesthetic in various guises, from bicycle chandeliers to cuboid standing figures to white on white squares – or it’s obverse, the equally visually ignorant brocante installation – as if without them modernism has no meaning. Well, it probably hasn’t; farewell to that idea, then.

Perhaps we (I mean “I”, of course) should just stop being so damnably, self-consciously clever about art. Maybe we (I) should stop thinking about lucidity and simplicity and wholeness and all those kinds of vaguely clever things that we think we know all about; and forget about trying to predict how the work will impact upon or affect the observer; and admit we cannot control what sort of context the work will be viewed in. Maybe instead we should just try to work out and focus on what is truly within our compass – what our ambition is for the content of our work. Maybe we should start to believe more in abstract content in the first place, that it is a thing of substance, real enough to think that it will be as meaningful as the best of figurative content, if we put our minds to it, and stop altogether thinking of it as being defined by a pathetic vocabulary of rectangles and flatness. How about some extravagant (but not excessive!) abstract content, and why not?

……………………………………………………………………………………..

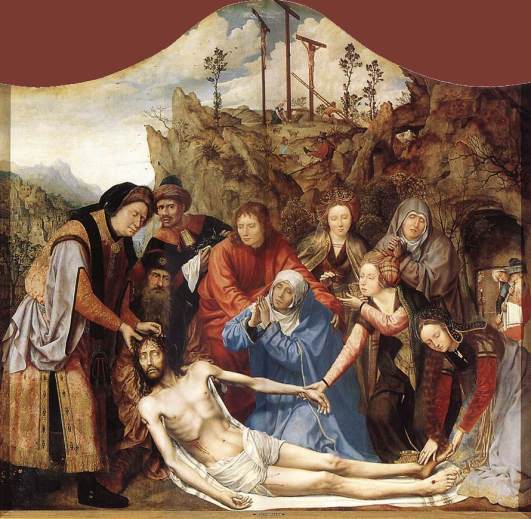

I’ve been looking at Flemish art recently, mainly from the 15th/16th centuries and mainly in collections in northern Belgium; painters such as Rogier van der Weyden, Quentin Massys, Gerard David, Hans Memling and others. These guys were focussed, fanatical, and fabulous, eager to move painting forward by investing it with more and yet more particular and specific content – stronger colour, more detail, more variety, more real space, more expressive humanity, more emotional display; more everything! But especially, more ‘real’. They maybe didn’t exactly know (like us) what that meant – did it mean painting every hair on the head of the Madonna, or did it mean making the space in a room around her ‘truer’ to life in some measure; or did it mean both? (It meant both!)

They really wanted to fully explore this new stronger reality that was opening up for painting, a much more three-dimensional and plastic spatiality than previously achieved, a much more expanded, varied, integrated space. But they didn’t have all the answers to hand, they had to try things out as they went. They found they could accommodate intense, ‘realistic’ detail into these invented spaces; they could change scale, going from the close-up still-life of an internal scene, out through a window to a road winding up a distant landscape, and keep it all within their grasp (well, they could if they were Rogier van der Weyden). They could reconcile huge great new amounts of complex three-dimensionality within two dimensions. To help them achieve this they stuck at the content and didn’t get too carried away with the artiness.

I’ve looked a lot at German renaissance art over the past few years too. One of my favourite paintings is Durer’s Paumgartner Altarpiece, c.1503 (boy, was painting happening around 1500!), in which the ostensible subject matter of the work is subsumed to the invention of a very particular and plasticised spatiality, which at the time was something radical, and still looks it. I don’t mean to imply that the Nativity itself, or indeed the portraits of the donor’s family, were unimportant to Durer; but the real content of the work as a painting is a direct result of Durer’s intense commitment to inventing and organising the specific space(s) within. There is a marked emphasis on the particular eccentricities of the space – on the architectural ins-and-outs, on the bizarre centrally-placed wooden roof-support dividing the picture, on the angled alcoves and roof appendages – rather than on a frontal display of the characters (how different from the beautiful frieze-like procession in Bellini’s Feast of the Gods – predicting Poussin – as cited in the recent Gouk essay). However, the figures are still crucial to the resultant spatiality – important, for example, in their emphatic orientation and the sight-lines thus created between them, such as the steep receeding diagonal between Joseph and Mary. Indeed, the clinching feature of this work is the two shepherds stepping up and into the space from out of the back-end of the picture. One of them gestures invitingly, the other strides up and in; brilliant. They, and the stanchion, are between Mary and Joseph in our sight, central to the painting. They, in relation to the stanchion, manipulate the back of the painting’s space, which is detailed with a landscape, but which is really articulated, spatially and psychologically, by these two characters. They usher us in as they themselves enter the space, which is both complex and plastic, a physical and inter-dependent entity in itself. So, is this a ’whole’ painting, is it a thing of beauty, is it a lucid and clear artistic statement? Don’t know, don’t care; it’s been made to be about something real, at all points of the compass.

When it comes to the depiction of three-dimensional space in painting, I could, of course, go back another hundred years to Giotto, but that would not really be where my interest lies at the moment. The innovations of perspective, though linked to painting’s ability to operate spatially, are only contributory factors in its plastic spatiality. The real business begins for me in northern Europe, where the focus is on the psychology and meaning of invented, constructed, complex spaces, like in the Durer, or the Gerard David above, which in the flesh is as sumptuously integrated a picture-space as you might wish for. In Italy (Tintoretto aside – he’s a very special case when it comes to spatiality), they were perhaps inclined a little more to thinking about composition, drawing, line, colour, and the sophisticated analysis of the processes of two-dimensionality. You know, all those things that abstract painters think far, far too much about…

So… I’ll leave you to make your own minds up about these three:

Hoyland, Caro, Noland is at Pace Gallery, London, Nov 20th 2015 – Jan 16th 2016.

Flemish art is in Antwerp, Bruges, Ghent and elsewhere, now – forever.

Some more or less random remarks on your comment:

Regarding Caro’s Stainless Piece C, you write: “And because it’s by Caro, and because he’s now dead (R.I.P.), and because it’s a piece of art history merchandising already, and because it’s the prestigious Pace Gallery; because of all this and more, and for no reason due to its inherent value, since it transparently has none, unless you view it through a thick haze of sentimental regret for simpler and more certain times in abstract art; this pathetic little piece of twaddle has become a luxury commodity, imbued with all the myths of modernism, reflecting back at us our own ‘good-housekeeping-modern-but-weren’t-we-ever-so-radical-back-in-the-sixties’ taste.”

(a) Works of “high modernism” in the 1960s and ‘70s – works that in “simpler and more certain times” (namely, when they were made and first shown) seemed interesting and challenging and exciting, have forty years later become a “luxury commodity” that are marketed by dealers to wealthy collectors and corporations that aren’t particularly interested in what made these works seem interesting and challenging and exciting. My question is this: is it this fact – namely, the fate of art-making and works of art in a culture that values newness and novelty for its own sake so that even the recent is relegated either to the status of “collectable classic” or alternatively to the trash-heap – that leads you to judge works by Caro and Noland to be artistically worthless, or do you really believe that they were without value to begin with, implying that modernism not only now seems but always was a con-game for the gullible?

Your comment seems to suggest both views at various points, as you concede that both Noland and Caro are not well represented at this particular show but I find that more than a touch of cynicism and bad temper pervades your remarks. Is it really Caro’s or Noland’s fault that you found yourself asking, “why I was going there at all; why was I supporting an occasion all but consanguineous with the excesses of super-class consumerist wealth and taste displayed in the ignoble designer-palaces that line Bond Street?” Is it fair to ask what sort of non-museum experience of more or less contemporary art would allow you a different kind of experience and why?

You answer your own question as follows: “And the reason, of course, is that despite shortcomings in the work, I persist in believing in a glimmer of something real and adventurous in painting and sculpture from this supposedly seminal period of abstract art, something that even now I feel linked to, tenuously. Am I perhaps deluded?”

I don’t know – are you? Am I? Is it not part of the essence of modernism as practiced by people like Caro and Noland that one never really knows what is “real and adventurous in painting and sculpture” apart from the experience of finding oneself convinced by it, and furthermore that artistic value is never (as it once was) established once and for all, and certainly not by the amount of “super-class consumerist wealth and taste” that is invested in an art work in the “ignoble designer-palaces that line Bond Street.” If that’s plausible, then it would be unrealistic to expect that one’s belief in a glimmer of something real and adventurous to be found in modernist painting and sculpture could be anything other than tenuous and always open to the suspicion – falling over one like a mood or bad weather – that your belief may be grounded in delusion.

b. You remark that Caro “listened too much to his painter friends” and that by the 1970s, Caro had “abandoned what little remained … of his slender hold on three-dimensionality.” I think this is unfair to Caro for several reasons. First, your example is Caro’s well-known “riffing on tables” –

“Well, any little thing can affect a degree of something-or-other in the observer, can’t it? A thing that looks a bit like a table, because it’s a flat sheet laid out horizontally, a couple of feet off the floor, can generate feelings of, well… ‘tableness’, good heavens, and off we go. Think of all the associations with tables… and if that table-thing has what look like chairs-backs round it, and a sort of drawer, and is called Survey…; or if that table-thing has some curvy edges, and it’s called Bare…; well, the feelings just keep on coming, don’t they…? And then there is the feeling of how ‘right’ it all feels… if you own the taste! It gets to the point where you wonder what the purpose of all this ‘feeling’ in abstract art is for.”

I think that Caro’s interest in tables began with his so-called table sculptures in about 1966. Tables are three-dimensional things. They are not pictorial. According to Fried, the table sculptures (those that rest on table tops) have to do with discovery of a new experience of scale (neither “big” nor “small”) for which there is no precedent in our ordinary world of experience. This is a discovery (if that’s what it is) that has to do with three-dimensionality, not flatness. After making some table pieces, Caro began making things that incorporate elements of “tableness” into the sculpture itself (e.g., Orangerie from 1969: https://www.pinterest.com/pin/166351779957703696/, among many others).

Tables (like doors) are things that we encounter every day of our lives; they play important but unacknowledged roles in our lives, allowing us to serve meals, place things, display things, gather around in celebration or sit alone in depression, and so on; we call these things “tables” and if asked we think we know why (they all conform to a Platonic idea, they share certain qualities in common, etc.) but in encountering a Caro we may realize that we don’t really know as much as we assumed about the world in which we live and die and we may even be inspired to find out why or how so much of our lives are lived in the dark as it were. Is this necessarily or only a matter of “owning the taste”? I suppose it is if examining how we perceive the world is only a matter of “feelings” that “just keep on coming…” But if that’s how we experience our lives then art – no art, Caro’s or anyone else’s – can save us.

c. Your reflection on the reductionism of Caro’s Stainless Piece C leads you to Robert Ryman’s dead-end all-white paintings, about which you ask, “Is this the democratisation of culture often referred to, such that everybody and anybody can get it, or even DIY-it? Or is it the exact opposite, the instant writing of art history in shallow gestures and big dollars, without the need to check on intrinsic value? Either way, are we anywhere near the endgame yet, please.” Didn’t Andy Warhol – following Marcel Duchamp – more or less demonstrate that these two alternatives are one and the same when marketed himself as a celebrity capable of generating an endless series of masterpieces simply by signing one-dollar bills? Modernism, as I understand it, refuses the limitless inflation of the “art work”, but modernism is as you point out, “over.” (I try to address this in my essay on Noland.)

I will close by applauding the resolve expressed in these sentences: “But, if we have got past that blindness, we haven’t yet gone quite so far as to discover or invent sufficiently robust abstract content such that it will again and again absolutely compel us to take things a lot further. The means to gain such ends as we can now envision for abstract painting and sculpture will be simultaneously more exacting, and yet less to-the-fore, and at the service of the content of the work – if not indivisible from it.”

LikeLiked by 1 person

Robin,

It’s pretty easy to get pissed about the art market and its associated press/media when you care about making, however it’s like the ‘housing’ market, the pricing of which is utterly disconnected from the concept of shelter or dwelling.

This is a commercial gallery (these market ‘values’ of course invade institutions too) and no it wasn’t a particularly strong show.

The Hoylands stood out.

One suspects the Noland and Caro were there to make ‘buyers’ more comfortable with offering the newly available Hoylands – being as we know somewhat disregarded out there in the land of J Jones etc…

No doubt Pace’s best stock of the already well known pairing are long collected/invested hence the somewhat weaker pieces.

A curated grouping in an institution or a pet project of a less commercial gallery might have sourced/loaned some stronger ones.

At this level, in that area of London price as a marker of quality is meaningless, it’s akin to permanent January transfers in football.

People that buy art assets don’t give a shit about the history of abstract metal sculpture or spatiality, once it has it’s price everyone else in the network has incentive to keep it that way, even if it’s a crappy Edwardian 2up2 down it’s a million £ trading token and thats that.

You don’t go to estate agents for architecture.

An object as a component of a wider story of sculpture or painting just doesn’t matter here, you know that Robin, you just had a different sort of gallery, Pace is a shop – Ab Fab.

It isn’t about democracy either, drag any number of ‘general public’ to abstraction they won’t get it, AG is on the money that we largely make it for ourselves, a few connoisseurs and very limited audience.

Modernism over – please not again, which modernism?

OK, there is precious little wiggle room left in Anglo American reductionism, but what about everything else?

That Durer is wonderful and a little odd too, I was imagining it without the people and it’s incredibly interesting because of all the construction going on.

Odd for all his commitment to high renaissance geometry, perspective and rigorous investigation he sticks with an archaic scale hierarchy to denote the status of various folk, almost a surrealist act.

This article is indeed running a little hot!

I agree with Carl that you’re just a bit too tough on Caro here, result of a kind of prolific Zappa like hyper-productivity problem.

Had Caro gone for the Smithian arts & crafts approach rather than the factory director there would be perhaps less around, but salesmen are always adept at bigging up ephemera anyway.

LikeLiked by 2 people

The more interesting part of his essay is the raising of German Renaissance painting. I’m in favour of calls to extravagant and complexity, but although written compellingly at the end of it all the general impression is vague and words like “spatiality’ like buzzwords. Where it seems to fall down is a lack of a specific way this could be of help to abstract art, or even of the difficulties which might be involved (which latter point might temper the attacks on others). Whether you agree with it or not Alan Gouk’s tracing of a modernist interest in light back through the history of painting to Vermeer at least has the advantage of identifying a common content – in the generally accepted meaning of the word – and a plausible technical continuity. I can’t see this here.

Such successes as illustrated were not just “a direct result of Durer’s intense commitment to inventing and organising the specific space(s) within” but of a whole range of technical and cultural achievements that made this organisation possible. Off the top of my head – the abstract ordering of perspective that had come up from the South + the discovery of the particularities of the natural world + the development of oil painting. The idea that this could be translated into abstract painting that develops just by “getting together some materials and working with them inventively until something emerges that makes some kind of visual sense. After that, it’s all about vision and ambition” seems almost bizarre.

Robin doesn’t want to mention contemporary painting, but the neo-impressionist work he seems to be interested in – Anne Smart’s, some Hofmann and his own paintings as seen on Twitter – is headed in the exactly opposed direction to the qualities he wants here, and highlights the problems of just “getting together some materials and working with them inventively”. This sort of painting – which can be beautiful, profound, successful – seems to me to as simple as that he berates. It’s just that the simplicity is broken up and dispersed a little.

LikeLike

Sam, indeed there is a sophisticated background toolset across all these works, how prepared are abstract painters to engage with more of it?

Once we take out the Christians and their chattels as ‘subject’ what else is going on in these masterpieces?

A hell of a lot of architectural underpinning, drawing, measuring, monochromatic underpainting and laborious glazing for a start.

All that means is in play, aside from the perspectives (the Durer is still most interesting) such ‘space’ as there is because of that technique.

More so than fresco and it’s necessary economy.

Can we reconcile such a long planned gestation of a painted image with the spontaneity required of abstract painting in order to expand the toolbox again?

Flatness may have run it’s course, but have we been preoccupied with Rembrandt’s nose, what about all that glazing in the windows on the world.

Can you have a grisaille abstraction?

What exactly is it then that painters can see to be re-employed from an de-populated old-master?

LikeLike

Sam, I think there is an inevitability about the vagueness that you refer to of ways that the figurative art that Robin admires might inform abstract painting (I think abstract sculpture would require a different conversation). I think the specificity that you seek (or lack of it that you are critical of) will only be revealed in work that responds to the challenges of producing ambitious work that is confident in its purpose (the abstract) but perhaps unsure as yet of its route,(the means) learning on the job I guess. I’m not persuaded that a consistently logical link or thread exists or can be manufactured that will prove to be a unifying theory bringing together figurative and abstract painting (as an aside I have never seen the point of making abstract works that claim direct descent from the figurative). At the same time I do believe that Robin is absolutely right when he insists that if abstract painting is to achieve the kinds of complexities that are seen in the painters that he highlights (and I would definitely include Vermeer, perhaps especially so) then a deeper understanding of what they achieve through the use of paint would seem not just sensible but necessary but not in the sense of seeking translatable qualities. (ie. putting a different slant on the figurative). Abstract art is different and all the more exciting for being so, otherwise why bother with it ?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Abstract art is indeed different, Terry, and I don’t know where Sam gets the idea from that I want to “translate” figurative anything into abstract anything. I make an argument here for content over aesthetics. I think many people consider abstract art can only be a matter of the latter, because it can have no content – which I strongly disagree with. And I bring in Flemish painting because it has recently impressed me a lot as a period of painting strong on content. I have no unifying theory behind this.

If Sam knows some other way to make abstract art, other than working inventively with materials, we should be told all about it. Odds on, it will turn out to be not abstract at all.

As for Carl’s comment, I cannot get very interested, despite his eulogy, in “tableness”. It’s not very three-dimensional, sculptural or spatial, whatever its role in real life. It’s not fit content for sculpture. Which brings me back to the topic here, namely, of inventing new abstract content fit for purpose…

LikeLike

Andrew has got at quite a lot of my meaning in his latest comment – I don’t think it is possible technically to seriously match the spaces Robin is raising as a comparison – and beating down other abstract artists with – with the means with which he limits abstract painting, the means by which abstract painting, or at least a substantial tranche of it has traditionally been limited. Of course it is it will probably be said that this is not true, that with just ‘inventiveness with materials’ There Are No Limits, but this is simply wishful thinking or rhetoric. And I think that difficulty at least needs to be faced. Quite how they are faced I have no idea, but not denying the problem might be a start? Would highly worked preparatory drawings be necessarily unabstract? Opaque shapes? Shaded objects? Perspectival recession?

Also I think, Robin that your distinction between aesthetics and content is hampered – to say the least – because of your highly personal uses of both words. As far as I can see here ‘content’ means an aesthetic, or a form of pictorial structure, of which you approve; and aesthetics is one of which you do not – perhaps we could coin the word “conthetics”? (btw the lapse back into the conventional use of the word content here “I think many people consider abstract art can only be a matter of the latter, because it can have no content” is very sneaky). Why is the centralised placement of the figures in a high renaissance picture not “content” in your use of the word; and the abrupt stylisation of David’s drapery not “aesthetic”?

This does not mean that the preference for Northern renaissance art isn’t significant – on the contrary I’d like to read you write more direct on it, minus the name-callng and theorising – rather that your categories don’t have any meaning outside the specific examples to which to use them to point. And there we are back to the problem of how to make use of the example of Durer et al. Of course this unfair of me as I’m not an artist, but I’d repeat my assertion that what seems to be the general trend of your aesthetic (!) preferences within contemporary painting is clearly divergent from the example from you past you are holding up here.

LikeLike

Robin, perhaps we might start getting somewhere if we concentrate on producing some ‘phenomenologically’ interesting surfaces rather than keep playing out subject – object, abstract – re-presentation dualism?

Reductionism, destruction etc… of image has long done it’s job we can start with ‘nothing’ so perhaps time not to fret and dig about in the toolbox with less heed to ‘associations’ thrown up afterward.

On the latest Brancaster video John Pollard looks like he has perhaps begun a little of such.

The ‘Flatness’ dogma still hangs about like Descartes.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Isn´t the common denominator of abstract and figurative art organisation?

Simply put, figurative art organises concepts such as persons, tables, mountains, wrinkles, noses etc. into works primarily accessible to our left-hand brain, supported by a parallel organisation of right-brain stuff that reinforces and emotionally charges the image (“the abstractness in figurative art”?).

Abstract art organises phenomena such as colours, lines and forms into works primarily accessible to our right-hand brain.

Both are arranging “independently expressive forms” to achieve some kind of communication. This is not as anti-intentionalist as Todd Cronan would have it. In both cases, the intentionality lies in the will to organise.

This is not a trivial, decorative enterprise. To one way of seeing things, organisation (the creation and maintenance of negative entropy) is simply what life does. Not just humankind but even primitive life-forms such as viruses are constantly engaged in organising stuff.

Reproduction (I´m thinking of the viruses), shopping, taking out the rubbish, running a business, reconciling emotions, theorizing, writing a story, justifying a course of action, engaging in politics, making sense of a life history – all of these can be seen as forms of organisation. The organisation of an artwork can thus reflect large parts or maybe even the whole of our existence.

If content lies in organisation, then the content of a figurative artwork can be deliberated and explained and expressed as the artist´s intention since it is (at least partly) organising linguistically apprehendable concepts. By the same token, the content of an abstract artwork (along with the abstract part of a figurative artwork) cannot be deliberated and explained and expressed as the artist´s intention since the stuff that has been organised is “left-brain”, pre-conceptual and pre-verbal. That doesn´t mean it isn´t there (unless you´re Daniel Dennett), but it makes it difficult to consciously intend anything in an abstract artwork apart from things like resolution, complexity, symmetry, clarity, which are concerned with the organisation itself rather than the stuff being organised.

I suppose one could talk about and explain conceptual associations generated by the work and even let the making be influenced by them, but this would be to relinquish abstract art´s most valuable property as a radically non-verbal communication, unconstrained by the prevailing grammar and conventions of language – a kind of free, right-brain counterpart to left-brain orthodoxy.

LikeLiked by 1 person

There’s some pretty good “tableness” going on in those Venetian paintings above, but a lot of other stuff too.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It is indeed tiresome to find Robin and other commenters still talking as if “modernism” is a phenomenon of the 1960’s. Modernism is Gauguin’s “Where do we come from” decorative originality, Van Gogh’s St. Remy ravines, Matisse’s Studio interiors, Moroccans, etc., Picasso’s Portrait of Fernande- Woman with pears 1909, Three Women 1909, and a host of “plastic and spatial” cubist masterpieces of 1908-1914, Kandinsky, Klee Mondrian, Van Doesburg, The Delaunays, Rietveldt , Frank Lloyd Wright, Le Corbusier, Mies, Pollock, Still, Rothko, and on and on. Read William J. Curtis’s concluding chapter in Modern Architecture Since 1900. Modernism is not and cannot be over, since it’s idealism, however bowdlerised, and it’s search for fundamental principles of plastic and spatial (( that’s my coinage, by the way) organisation are still just as “relevant” as ever.

When is it going to dawn on Robin that the types of spatial organisation found in Netherlandish and Pre-Renaissance painting, while they may stimulate the imagination of a sculptor, are antithetical to the aims of abstraction in painting of all the artists listed above. Abstract content, whatever that is, will not be found by reverting to a conception of pictorial space that served the 15th and 16th centuries. The gap between Robin’ taste for old painting and his taste for his Brancaster colleagues is ever widening, and this is reflected in the latest examples of his own efforts in paint. On this I am in agreement with Sam.

LikeLike

Whilst I understand that for you, Alan, modernism starts anywhere and everywhere, so long as there is some degree of frosted-glass surface continuity involved (bit of a bugger when it comes to sculpture), ‘high’ modernism and the descent into minimalism with a small ‘m’, which covers the abstract painters you mention after Matisse and Picasso (barring the two architects you sneak in), as I focus on it here, is indeed a phenomenon of the sixties. What’s more I am indeed “antithetical to the aims of abstraction in painting of all the artists [so] listed”. Yes, and very much so. That list is the rather tiresome thing.

As well as agreeing with Sam about my own pathetic efforts in paint that presumably you have studied in depth, the two of you, on Twitter, you make the same incorrect assumption; where exactly am I proposing that anything should be reverted to?

I’m for moving on. You, by contrast, seem intent on sticking with the past, albeit a recent manifestation of it. I can see why.

LikeLike

“Modernism is not and cannot be over, since it’s idealism, however bowdlerised, and it’s search for fundamental principles of plastic and spatial (( that’s my coinage, by the way) organisation are still just as “relevant” as ever.”

In the pre-modernism past, one could identify specific authoritative conventions (together with associated authoritative institutions such as the church, various patronage systems, etc.) that were able to guarantee a thing’s identity as a painting, sculpture, sonnet, sonata, etc.). What seemed to count (by virtue of compliance with known rules of the convention) really did count (e.g., as a painting, although not necessarily a good pointing). Modernism came into being when the inference expressed in the last sentence is no longer valid. That happened when institutions lost their traditional authority and inherited conventions lost their power to persuade. What seemed to count, didn’t; adherence to known conventions produced the MERELY conventional, the hackneyed, the used-up, etc.; whereas the presence of the authentic became recognized by way of the scandal it produced and quickly thereafter (when modernism was popularized as the avant-garde) the scandalous became a guarantor and thus a parody of the authentic.

In my view, modernism expresses a commitment to the continued viability of art-making in the absence of conventions that GUARANTEE its continued existence; such conventions are necesssarily absent in a time when nobody really seems to know why people bother with making art at all, except as a high-end luxury good to be consumed by the very wealthy. In that sense, modernism is necessarily “idealism” as you say and its “search for fundamental principles of plastic and spacial organization” is a search for conventions that – if only for a passing moment and if only in a particular work or series of works – are capable of instilling in the viewer the conviction that he or she is in the presence of a work of art – meaning, a conviction that one is in the presence of the Real. (Modernism’s idealism is inherently subject to “bowdlerization” (as you put it) because: unable to draw on inherited authoritative conventions, the artist must discover new conventions and these new conventions have no authority beyond the authority of one’s own experience, which may or may not be in good faith.) (To make the Real present has always been and always will be the transcendent goal of art in general; but it’s now possible to envision a time when the Real will itself cease to be of interest.)

LikeLike

“High modernism” is a fiction of the rhetoric of the sixties, misplaced from its true location. And as for particularised content, I thought I had nailed that canard to the tent-pole of dreams with my comments on the Rolfe/Cronan dialogue.

“Content” as you define it Carries no guarantee or promise of pictorial substance, and has been a recipe for some truly awful modern examples. (John Walker and Christopher Le Brun and a host of others too awful to mention spring to mind).

Even Frank Auerbach, a figurative painter, has as he developed realised the necessity, albeit reluctantly, for a taut dialogue between a plane-defined perspectival depth, and surface unity. (He no doubt likes the Tintoretto too.) Why? Because of the trajectory of modern art, with which he has had to make an accommodation despite a constitutional abhorrence for it.

To vent your invective on the very soft target of some of the weakest Noland’s and Caro’s to have escaped their studios in order to vilify 60s “modernism” instead of facing up to the issues posed by Auerbach, and it should be said, Lanyon too,suggests a blindness to the implications of your own advocacy.

LikeLike

You want guarantees? Suggest you change careers.

LikeLike

And your disaffection for the list indicates an ill-at homeless with the whole of modern painting since Cezanne. I forgot to add the late Braque Atelier paintings one of which you reproduced with approval some time back. Thank heavens for small mercies. I’ll leave others to decide on that. I’m out.

LikeLike

Hi Robin,

It seems to me that you’re making a real break here. You are trying to see things differently, and I respect that immensely. I especially enjoyed the paragraph that contained this:

“Maybe instead we should just try to work out and focus on what is truly within our compass – what our ambition is for the content of our work. Maybe we should start to believe more in abstract content in the first place, that it is a thing of substance, real enough to think that it will be as meaningful as the best of figurative content…”

I think both Sam and Alan are right about the implications of your essay. What you infer and aver about what is exciting in painting is quite different from what you’ve shown us among your professional colleagues and in your own paintings. This must keep you up at night.

Alan is also quite right in saying that your ideas are anathema to Modernist abstraction. But even in the face of these strong connections and friendships you’ve had the guts to say these things, and you’ve made the forceful argument that Modernism has had its day and it’s time to move on.

Good luck, Robin! I look forward to hearing more about what you discover!

Abstraction without Modernism sounds exciting to me.

LikeLike

In a triumph of content over aesthetics, an Abcrit comment achieves the status of art: https://soundcloud.com/zolani-stewart/a-dramatic-reading-of-a-comment-on-abtract-criticalcom

Next year we’re hoping for a full Panto.

LikeLike

Very disappointed by the poor quality of the ‘dramatic reading’. The sonorous tones of Guilgud would have done it justice.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The Soundcloud reading is a little too fast (and American) for me. I printed off Robin’s provocative article and read it out loud to my daughter’s gerbils in my best Alan Whicker/Jonathan Meades voice.

LikeLike

Abstraction without modernism is like Judaism without the Torah, or Trump without the jokes. “Plastic and spatial” is a classic modernist concept with an August pedigree stretching from Wolfflin, Fry, F.L.Wright, Corb, Rietveldt, Gabo, Hofmann, A.Stokes etc. ( the computer insists on turning August into a month).

And on “high modernism”, I don’t think Greenberg, Fried, Bannard and al. Ever made such a claim for their period. A constant refrain through Greenberg’s writing is to locate high modernism with the analytical and synthetic cubism of Braque and Picasso from 1910-17-20.

Robin keeps stubbornly repeating these gaffes, like a bull charging at a wide open gate,(see The Abduction of Europa by Rembrandt -Getty Museum, L.A.). Merry Christmas!.

LikeLike

I thought you were out.

So “plastic and spatial” is both your coinage and a classic modernist concept. Presumably you thought of it first, though. And presumably nothing prior to modernism (let’s see now, when did that start…) can be either plastic or spatial?

By the way, who was al. Ever? Your punctuation is as nacreously opalescent as your argument. Happy New Year.!.

LikeLike

If you read your latest comment again, I think you’ll see how silly it sounds. Definitely I’m out now. See you in 2016.

LikeLike

Of course, abstraction is not just rectangles and surfaces – and painting (like sculpture and baking cakes) is more than “plastic and spatial”. Is the ‘real’ that Robin mentions above a shared humanity? (Sounds wishy washy, I know.) Or triggering/requiring psychological, thoughtful, connections from a viewer – albeit in the context of the time or in looking back. Or is there an implied universality in ‘good’ art worthy of the categorisation? So, what then for subjectivity? Do we need interpreters (e.g. art historians, critics, Abcrit writers) to enlighten us?

As a painter I still struggle with the notion that there is a pure abstract image, devoid of some kind of underlying content. Surely there is always a ‘subject’ that matters that is external to what is placed on the canvas that informs what the painter can do with his/her materials? This might just be ambition?

As for minimalism (which is mentioned somewhere above), I could live with an Agnes Martin for ever (even though she did not connect entirely with the term). I wouldn’t mind a Gouk on my wall too…

By the way – do we vote for our favourite of the three paintings at the end of the article? My vote goes to Titian’s “Supper at Emma’s”. (I like the spellcheck rejection of Emmaus – especially as I am an atheist).

LikeLike

Having had a few days off to rue my sins against the unassailable and holy modernist abstract canon; and despite Carl’s elegant moral arguments for modernism’s continuing resistance to the discombobulations of contemporary art and life (though I suspect nothing is new in the moral panic stakes); and despite Alan’s refusal to entertain in the least the concept of abstract content, and despite his spiritualist invocation of the dog-eared list of modernist greats (Rothko, Alan? Really? Did you see his show of late work at Tate Modern? What are you claiming for this utterly boring painter?) and despite Sam’s insistence that what I do is not what I say and what I say is not what I mean (though he seems to have trouble spelling it out); and despite Mark’s insistence that I don’t (or can’t) do what I say anyway (a barb I could certainly return with interest); and despite Gielgud’s unavailability to dramatise comments (I would settle for David Sedaris); despite all this, I am unrepentant…

…because “wholeness” might be better thought of as the underlying completeness, richness, complexity and variety of the abstract content of the work, rather than the superficial unity of some simplistic abstract aesthetic, which time and again leads to a repetitive predictability. I would suggest that the content to be found within the existing abstract modernist canon is often incomplete or partial when compared to the Flemish art that I cite here, which is more varied, rounded and inclusive (to look at!), within each individual work. To use a literary analogy, is gives us the full-length, in-depth novel, with out-and-out characterisation and plotline – a source of endless interest; whereas abstract modernism shows us, at best, the clever short story, and at worst, merely the fragments of a language. It’s that simple, isn’t it? More to look at, more to marvel at. We don’t really need to know about left brains and right brains.

I’m not in any way advocating anyone starts mimicking the spaces (or anything else) of figurative art; I am suggesting (yet again, tiresomely) that abstract painters and sculptors compare their output with the best achievements of figuration, which of course includes some great modernist art, if that’s what you want to call it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Shall I spell it out then. The paintings (your current ones, Anne Smart’s + the Hofmann’s you have posted recently) chiefly function on the micro-level with small transitions and flecks of colours. On the macro-level they are very often less interesting, and just as simple as a Hoyland, perhaps more so (because they are a basic more or less whole, that is just broken up with said transitions, flecks of colour). The interest is the trees rather than the wood, amorphous, shifting shapes, a not-quite all-overness. All this is far, far, far away from the clearly stamped-out opaque shapes, perspectival recessions, architectural structures and incredible detail of the paintings you admire here (and which you use as a tool to attack the work of others). It’s worth pointing out that it’s only Alan G who is arguing you need to show more respect to the modernist canon – both Mark and I argue that the painting you generally support is very much within that canon and are trying to suggest that what you are compellingly arguing for would need to break a few more of the rules of the canon if it is match the ambitions your article holds. You said that it is likely that the results would not be abstract – maybe that is a risk worth taking. Of course it is easy for me to say this as I’m not an artist, but I still think it worth saying.

LikeLike

Glad to know my article holds ambitions. Best if you take to task things you’ve seen.

LikeLike

I’m glad to see that Robin hasn’t lost any of his trade mark wit, but for my sanity (and perhaps for the sanity of others) I’d prefer an article in which Robin refrains from a series of funny, but ultimately inert, subjective judgements i.e.: “all great art seems…spontaneous, effortless and direct” -I’d say that the quality of the Gerard David is in direct proportion to the visible effort and planning required to execute such a fine work- instead, I’d like Robin to offer a lexicon of sorts where he explicitly defines the nebulous terms he throws around like so many darts to the board.

Distinguishing between ‘abstract’ and ‘abstraction’ is a little tough to parse, perhaps you mean ‘non-objective’? And just what is ‘abstract content’ besides a linguistic eel so slippery that even its wielder cannot adequately grasp it. These arguments on AbCrit seem forever locked in the gravitational pull of misunderstanding -or misinterpreting- words with no commonly understood usage to begin with. Its a bit like watching two people argue vehemently about the size of Jupiter where one person thinks they’re discussing a planet, the other a Roman god.

Just be plain about what you mean. Robin wonders whether or not its possible to invest non-objective painting with the same visual complexity, meaning and emotional force of the best representational painting. The answer is ‘no’, because they are two different types of depiction. One relies on a complex illusion of space and structure buttressed by signs and representations that are universally intelligible. The other can be structurally and spatially complex, but without recourse to representation it cannot communicate the same volume of meaning. Each mode offers its own unique satisfactions and comparing them is, as I have said before, futile and not enlightening.

LikeLike

I’ll start the lexicon:

Abstract content – good paintings have this

Aesthetics – bad paintings have this

Good Paintings – those with abstract content

Bad Paintings – those with aesthetics

As for the rest, I’m out

LikeLike

Thanks for that Sam, very helpful and true.

For you we could have:

Good Paintings – anything with straight lines, a bit Neo-Op; or figurative paintings done from an aeroplane so they look a bit abstract.

Bad Paintings – anything with bits of paint in, as seen on Twitter.

LikeLike

Re: Sam’s lexicon.

Are there ‘good’ and ‘bad’ aesthetics?

Aesthetics is sometimes associated with acquired ‘taste’ from within cultural stereotypes. Many of my former undergraduate students thought that aesthetics was a pointless “art for art’s sake” approach to making paintings – sometimes associated with ’empty’ abstraction.

I think of aesthetics (in the visual arts) as being about pictorial judgement, including composition, visual impact, choice of colour etc.

LikeLike

I don’t believe that it is possible for abstract artists to invest their work with the ‘SAME’ visual complexity etc. of the best representational painting. I interpret what Robin is saying as a question of artists demanding of their work an equivalent level of visual complexity with all that might be attendant with and contained within that complexity. If you like, a visual journey as exciting and imaginative as the figurative but by different (non-depictive) vehicular means and with a different destination.

LikeLike

Quite so.

LikeLike

Perhaps, Alan, you ought to write the article that you would “prefer” yourself. If you read mine carefully you will find that in fact we agree about the Gerard David and how it is made.

I have set out the difference between “abstract art” and “abstraction” quite few times.

“Abstract content”, meanwhile, seems a really sound idea. I don’t think it is slipperly, but, yes, being as it’s abstract, difficult to verbalise; and there is not much of it to discuss in the Pace show.

LikeLike

On a more serious note, this article by Carl has an interesting and not unrelated viewpoint on content in photography: http://ctheory.net/articles.aspx?id=743

LikeLiked by 1 person

I have some trouble understanding the idea of “abstract content”. I personally have no way of understanding “abstraction” apart from the context of “modernism” as a historical phenomenon in Western art. That is: at some point certain conventions that were essential to the arts of painting and sculpture (and of music and literature and even philosophy) lost their capacity to convince the beholder. At that point, these arts faced the threat of being merely conventional – trite, academic, contrived and meaningless. (For me, an early and rather heroic confrontation of this threat appears in the paintings of Courbet with his passion (if not compulsion) to project the “Real” onto his canvas.)

In painting, those conventions were those that artists used to create the illusion of three-dimensional space on a flat surface. Ambitious painting therefore had to became “non-figurative” or “non-objective” – meaning, free of the need to depict objects of the kind we see and touch or imagine in the world. But a non-figurative painting – which does not depict objects – tends to be experienced as an object in its own right, or to suggest a kind of space within which objects might appear. And if a painting is (nothing more than) an object, even an object of a very particular specialized kind, then the art of painting has no point.

I take abstraction (or abstractness) as the artwork’s achieved neutralization of its own objecthood. In our secular world dominated by the ideals of science and technology (and their opposites, willed ignorance, primitivism, etc.), objecthood that is never truly defeated once and for all, but can be and is suspended in the experience of successful works of modernist art. Abstractness therefore cannot be a quality of any painting or sculpture, because qualities adhere to things and a work of art is not a thing. (For example, Kandinsky’s paintings are non-figurative but the configurations of color and line within the picture usually appear as objects of some kind that are suspended within an imagined three-dimensional space. Likewise, Mondrian’s characteristic paintings strike me as objects, perhaps concrete illustrations of intellectual ideas. For these reasons, Kandinsky’s and Mondrian’s paintings, whatever their merits, are non-figurative but they aren’t abstract.) Abstractness, when it happens, is a modality of artistic significance, a way in which human significance is achieved and conveyed in the course of lives that are all too literal.

LikeLiked by 1 person

A fascinating insight Carl. The notion that “abstractness” is always a quality that attaches itself to a recognizable thing is, I think, the fatal flaw in Robin’s analysis.

Just as we cannot objectively measure reality because we cannot escape to a neutral vantage point from which to observe it, we too cannot achieve a pure “abstractness” or “abstract content” because we will always require a root cause or first principle which is not abstract from which we proceed to abstract from. Hence my objection to Robin’s use of the term “abstract” all together when what he really seems to mean is “non-objective” or “non-referential”. Unfortunately these two concepts are at best idealist, and at worst useless since we cannot create in a visual vacuum. Thus even the most non-referential works of art ultimately remind the viewer of something.

In fact, I’d go so far as to argue that much contemporary abstraction is boring precisely because the work has so self-consciously severed its connection with the very figurative space we inhabit. The “big bang” of 20th century abstraction was always more sociological than aesthetic in its character, and so 21st century abstraction out to be more aesthetic, i.e. rooted in a physical experience of the world perceived through the body’s senses.

LikeLike

So do you agree, Alan (P), with Carl that “door-ness” and “table-ness” are abstract?

We are a very long way apart on this. I would argue precisely the opposite – that abstract art is mostly boring because it continues to pretend that it has significant subject-matter or associations (anything from “table-ness” to “look-a-bit-like-ness” to “spiritualised-one-ness” – a veritable crank’s charter) which supposedly renders profound content; and so the actuality of the work itself need not be progressed by the artist too much beyond simplistic forms (Mondrian and Newman being very good examples). If, however, you (as an artist) drop any idea about subject-matter and associational material, and concentrate on what I (tentatively) call abstract content, there is a better chance altogether of making the actuality of the work not only far more interesting, exciting and unconventional, because that’s all you have, but also of making it truly meaningful, in and of itself.

The business of finding meaning in non-referential experiences I dealt with in an article on Gillian Ayres early work http://abstractcritical.com/article/gillian-ayres-paintings-from-the-50s/index.html, but to summarise: if when out walking you crest a hill to be shown in the distance a magnificent mountain range, which grabs you and moves you, such an experience I would describe as meaningful. If you have never seen that particular mountain range before, it will have no associational baggage, but that hardly disqualifies it from meaningfulness if you are the sort of person who responds to such visual stimuli (if you are not, too bad, you probably don’t get visual art either). Of course, if you are on a homeward journey and the mountain range is the land of your childhood, it will be full of many kinds of associations. But those associations and their attached sentiments might well cloud the vision before you, and, paradoxically, obscure the meaningfulness of the visual experience itself.

So what does such an experience have to do with the conventions of painting that Carl insists upon? Nothing that I can see – rather the opposite, that the unconventional shock of great art shifts all that out of the way and we experience the thing, perhaps briefly but significantly, unmodified by a cultural contextualisation of any sort. I have jumped from talking about mountains to talking about art, but they are related. As the late, great Bryan Robertson said, art is not a communication in language so much as a revelation. The unmediated experience of painting or sculpture can be a very similar experience to the unmediated mountain range experience. That certainly is what I feel looking at good art, both figurative and abstract, before (though sometimes, indeed, after) I know anything about the subject-matter or context of the work I’m seeing.

The great potential of abstract art (in almost direct opposition to abstraction, which is essentially figuration disguised) is that it can attempt to deal directly with such experiences. In the end it may well be different from the “mountain” experience, more enduring perhaps, because it is the product of another mind and another’s sensibility. But this has nothing to do with purity or idealism; if you are into those things, best become a conceptual artist, because this “abstractness” thing is something else altogether.

LikeLike

In the sense that doors and tables posses abstract qualities which in part define their status as artifact kinds, or perceptually distinctive objects, yes I agree with Carl. As I’ve said, because abstraction is a process of distortion, it cannot exist without some non-abstract first cause. This is my issue with your use of the term “abstraction” to denigrate art you don’t care for and “abstract” to praise art you like, especially when terms such as “non-objective” or “non-referential” would be far more precise in describing the art and “content” you champion.

As to your hike in the woods, I’m glad it was pleasant, but again your being too imprecise with the terms you’ve employed. A scenic vista composed of far off mountains may indeed be moving, uplifting, or even frightening, but it is not meaningful; unless you believe that the mountains were placed there with specific intent that you must now interpret.

Neither are the mountains experienced without context. In fact, your perception of how high, rugged, near or far, beautiful or ugly the mountains are are based upon instantaneous and often unconscious comparisons with similar experiences that have come before. By the time one is old enough to use phrases such as “unmediated experiences” one has lost the capacity to have them.

Now years later you might come to regard the experience of that landscape as having been meaningful for you (in the affective sense), as it was the moment you gave up art and turned to forestry conservation, but alas, the scene itself was devoid of intent, and thus was not ‘meant’.

Regarding painting, on one hand you’re correct, beholding a painting can, like beholding a mountain scene- be uplifting, moving, pleasurable, or frightening, but on the other hand a painting -even the non-objective variety- is completely different than the mountain scene as it’s creation involves artistic choice and intent, and therefore is pregnant with possible meaning. Of course its perfectly possible to enjoy a work based solely upon your physiological/emotional response to it, as you seem to prefer, but that would mean eviscerating any claims towards the objectivity of judgement which you periodically clamor for.

I simply fail to see how non-objective work can deal with the type of experiences you describe “more directly” than figurative or abstract works in anything then but a strictly privatized manner. How then can you determine the veracity of Noland or Caro’s experience as it is embodied in their work?

LikeLike

Reading and thinking about Ellsworth Kelly has prompted the following thought:

That the most significant divide within the visual arts is not between figuration and abstraction, but between works that primarily create and modify their own space, and those that primarily modify the space around them. The former are tendentially self-contained, frameable, intimate and expressive, while the latter are unframeable and tendentially more impersonal (though not inhuman) and architectural and/or didactic rather than expressive. The reception of the former is an encounter, that of the latter an immersion.

That would put much of painting in the first category, but some (most?) minimalist painting would be in the second, along with Ellsworth Kelly, Light and Space etc. I can imagine there would be a similar division in sculpture.

I have not seen the Pace Exhibition and have no wish to defend it, but maybe the minimalist works have not been given the space (quantitatively and qualitatively) they need to be complete. Assessing them from the exhibition would then be like assessing my swimming without a pool.

LikeLike

Still trying to sort out all that’s going on here. Robin has juxtaposed his experience of the not so great Pace show with his experience of some great work by Flemish and German Renaissance artists, and provoked a terrific series of comments. There’s some sense in which the distance between the work at Pace and the Renaissance work is “unbridgeable” (to borrow a word Robin used elsewhere recently). The work at Pace is probably “high-priced”/“over-priced.” The Renaissance work is maybe “priceless”—but maybe meaningless in some sense today just because a price can’t be attached to it. This juxtaposition of Robin’s—“unbridgeable” distances, in general—is/are very much a part of the world we live in—very much a “problem” demanding comments.

I’d like to throw two more words into the mix: “sincerity” and “authenticity.” “Sincerity and Authenticity” is the title of a terrific 1972 book by Lionel Trilling, a book I’ve been reading recently because of Jed Perl’s recent, very interesting essay in the NY Review of Books: http://www.nybooks.com/articles/2015/09/24/perils-painting-now/. There’s a kind of unbridgeable distance between Jed’s sensibility and a lot of contemporary painting: bemusement or befuddlement is as close as he can get. But Trilling’s ideas help/begin to bridge the gap.

Two excerpts from Jed’s essay:

“Trilling’s argument was grounded in the strong opposition he saw between the nature of sincerity and the nature of authenticity. Sincerity, according to Trilling, is essentially social, “the necessity of expressing and guaranteeing” oneself to the public. Authenticity is a very different matter, an obsession with individual experience that Trilling believes has in modern times come more and more to overwhelm sincerity. Sincerity involves a “rhetoric of avowal”—a balancing, somehow, of “the troubled ambiguity of the personal life” and the “unshadowed manifestness of the public life.””

“What was being lost was the dynamic relationship between sincerity and authenticity that had given the work of an artist such as Cezanne its slow-building power. For Cezanne, the sincerity of his commitment to traditional stylistic legibility was constantly challenged by the authenticity of his idiosyncratic experience of nature. It is Cezanne’s double allegiance—to the sincerity of tradition and the authenticity of his own perceptions of form—that has made his work central for artists from Matisse, Picasso, and Braque down to our own day.”

Alan, Sam, are these definitions adequate/at all useful? It’s great you’re so hungry for meaning. You provoked Carl’s great comment about abstractness as a “modality of artistic significance.” But Carl leaves me with “questions” about “form” and “objecthood.” Start talking: you can’t stop. Isaiah Berlin wrote a great book about romanticism. He begins, as I vaguely recall: Wanna definition of romanticism? Fuhgeddaboudit.

I think it’s kind of fun to think, just for a moment, of Alan Gouk as a sincere, in Trilling’s sense of the word, painter—and to think of Robin as an authentic painter. (Note: I’ve never seen their paintings except in reproductions.) It’s fun (for me) to think of Brancusi and Calder as sincere sculptors. I just Amazoned myself a copy of the nice little (700 page) Curtis book on modern architecture that Mr. Gouk recommends in an earlier comment. The chapter Alan (Gouk) refers to is titled “Modernity, Tradition, Authenticity.” (There’s no mention of sincerity in the chapter.) And the other day Roberta Smith reviewed the Rudolf Stingel show in NYC now: http://www.nytimes.com/2016/01/01/arts/design/review-rudolf-stingel-at-nahmad-contemporary-making-crowd-sourced-art.html?ref=design&_r=0. (Note: I have seen the Stingel show: lucky me!) Is the distance between Stingel’s work and, Alan’s/Robin’s unbridgeable? No. Alan and Robin are Nick Nolte and Eddie Murphy. They’re in a 1982 movie called “48 Hours.” They’re the heroes. Rudolf Stingel is in the same movie: he’s the wicked city of San Francisco.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I really don’t understand the difficulties around the use of the word ‘abstract’ as it is distinct from ‘abstraction’. Most (including the major dictionaries) would accept that non-objective, non-referential, non-representational etc. are synonymous with abstract so why not choose a perfectly adequate term that isn’t a ‘non’ whatever.

LikeLike

You’re right Terry, but the word ‘abstract’ applies equally to works that are referential and representational. Take, for example, Picasso’s “Portrait of Kahnwieler”. I don’t want to sound like Officer Surly of the grammar police, but I think discussions about art are be better served without the use of equivocal language, especially when more precise terms are available.

LikeLike

Alan, the Portrait Of Kahnweiler ( 1910, Institute of Chicago, and I appreciate that there are others) that I have looked at (on-screen) is clearly a product of the process of abstraction. It is not in my view an abstract painting and does not invite any kind of meaningful application of the word abstract to what it presents visually. Perhaps the difficulty is that discussions around the word abstract far too often become focused on matters other than the visual. What precisely is it then that is visually abstract about the Kahnweiler portrait?

LikeLike

Perhaps, Alan, we are getting down to it now. You have clearly stated your position – that meaning in art can only come from the interpretation of the artist’s intention; and that something that is quite simply marvellous and compelling to look at can never be meaningful, if it is without intention. That’s crazy. If it were true, it would be a lot easier if artists just wrote down what their intentions were (they did and it’s called conceptual art). What about fortuitousness in the making of art; does that never figure? You must live in a different world. It doesn’t surprise me that you don’t get “abstract content”.

It’s been very interesting thinking about Todd Cronan’s views on intentionality (I think he underplays fortuitousness too), and how those might relate to making abstract art – how might one reconcile intentionality with spontaneity (and indeed the accidental), which are surely requirements of a full and proper approach to making new abstract painting and sculpture now. But my understanding of that intentionality does not encompass your definition of meaning, which seems to require a literal or literary explanation of purpose.

I find it impossible, even with the most focussed of artists – say Cezanne – to believe that I am in touch with their day-to-day intentions about individual works. I might, if I study their oeuvre enough, get a partial handle on the kind of intentionality that I think directs their path overall, which is what I interpret Todd’s version of intentionality to be, but trying to decipher the intentions behind an individual painting or sculpture, and then extrapolate the meaning from that, is not only impossible – since we have no idea whether or not any intentions were achieved – but utterly beside the point. I have no idea what determining “the veracity of Noland or Caro’s experience as it is embodied in their work” would entail, nor what the purpose of doing so would be. How can I know their experience? I can only know their art, which is where I find meaning.

By the way, quite where I have “denigrated” all abstraction I don’t know. We could agree that Picasso’s “Portrait of Kahnwieler” is indeed an abstraction. So, to some degree, is almost all figurative art (shall we exclude photo-realism?). And we could agree that abstraction is distortion (with which I have no problem). That’s why I want to distinguish it from abstract art, which is not a distortion of anything, because it doesn’t start from anything that could be distorted.

I for one want very much to stick with “abstract”, difficult though it is. “Non-objective” sounds a bit too constructivist (and subjective!) for my liking.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I can’t help but think that a few beers and an hour or so at the bar would clear all this up…..alas, I think you’re taking my train of thought and putting it on the wrong track, Robin. I am emphatically not saying “that something that is quite simply marvelous and compelling to look at can never be meaningful, if it is without intention” Indeed as I said, it can be meaningful to you, in a privatized way, but a luminous sunset or glistening waterfall is without meaning in the way that human acts or creations are meaningful. What’s crazy about that?

At any rate, as I’ve said previously in some 1000 word response somewhere on AbCrit, we respond to works of art in different ways at different times. When I look at a Titian, I’m primarily moved by the formal relationships within the work. I’m blown away by the composition and color!! I marvel at how Titian can direct my attention to an important point just by a shift in value. Those moments are ‘meant’ as it was Titian’s aim that I be visually directed by his use of the ‘plastic means’ at his disposal. But nowhere in that initial experience am I consciously seeking meaning, at least not yet. But it is there, embodied in the form of the work.