Kenneth Noland, “That”, 1958-59, acrylic resin on canvas, 81.75 x 81.75 inches. © 1997 Kenneth Noland, licensed by VAGA, New York, N.Y.

Kenneth Noland’s Discovery

Kenneth Noland famously declared that his breakthrough as a painter occurred when he “discovered the center of the canvas”[i] in the late 1950s. Noland’s “discovery” produced a series of well-known paintings executed between 1958 and 1962 based on the placement of concentric circles of various colors in varying widths radiating out from the exact center toward but never reaching the four edges of the picture, usually comprising a six-foot square.

This essay addresses the question of what exactly Noland can be said to have “discovered” and why the concept of “discovery” is crucial in understanding the nature of modernist painting and sculpture.

Background: The Modernist Situation

In 1962 Clement Greenberg wrote:

“Under the testing of modernism, more and more of the conventions of the art of painting have shown themselves to be dispensable, unessential. By now it has been established, it would seem, that the irreducible essence of pictorial art consists in but two constitutive conventions or norms: flatness and the delimitation of flatness; and that the observance of merely these two norms is enough to create an object which can be experienced as a picture: thus, a stretched or tacked-up canvas already exists as a picture – though not necessarily a successful one. (The paradoxical outcome of this reduction has been not to contract, but actually to expand the possibilities of the pictorial: much more than before now lends itself to being experienced pictorially or in meaningful relation to the pictorial: all sorts of large and small items that used to belong entirely to the realm of the arbitrary and the visually meaningless.)”[ii]

However, what Greenberg refers to as a “paradoxical outcome” may not be paradoxical at all: the search for the “irreducible essence of pictorial art” revealed that pictorial art has no irreducible essence at all. This would imply that the distinction between art and non-art is really arbitrary; there is ultimately no meaningful distinction between objects that are considered “art” (for example, in the political economy of a particular market sector) and ordinary objects in the world.

There are at least two modes of response to this state of affairs. The first response, emphasizing that “works of art” have nothing inherently special about them, asks why we cannot conceive of literally any ordinary object as an art object. And the answer is: of course we can! We need only establish the mise-en-scene, by placing the object in an “art context” – for example, a white and featureless gallery space, where people are invited to experience (ironically, sardonically, smugly, with a knowing smirk) the survival of art in a post-art world.

A second response refuses the promiscuous expansion of the pictorial, and seeks on the contrary a contraction of its realm – a reduction based not on a timeless identification of the “irreducible essence” of pictorial art as such but on a declaration of those norms or conventions that can, in the artist’s present moment, convey personal feeling in ways that compel conviction as pictures. Because “essence” is a matter of conviction rather than theory, modernism declares the absolute priority of quality and value; the question, “Is it art?” is always a form of the question, “Is it good art?” As Greenberg puts it in the same essay (referring to Newman, Rothko and Still), “[t]he question now asked through their art is no longer what constitutes art, or the art of painting, as such, but what irreducibly constitutes good art as such. Or rather, what is the ultimate source of value or quality in art?”[iii]

The unlimited expansion of the realm of the pictorial – and the consequent imperative to contract that realm around axis of quality – is only possible and only required at a particular historical moment when inherited conventions no longer possess their power to convince. At that moment, the continued existence of the art of painting is no longer physically assured. The modernist work shows that line and color and shape have only the significance we give them, and that we give these physical materials significance by arranging them in ways that make sense. For us human (finite) beings, making sense means making ourselves understood, that is, expressing ourselves. And because we are embodied, earth-bound beings, non-transparent but not on that account opaque, every expression of the self is a particular expression, by way of a particular medium, using specific physical materials, to a specific point. To say that we express ourselves by way of a particular medium is to say that in expressing ourselves, we make that medium as our own. For an artist like Kenneth Noland in the 1950s, existing conventions could no longer serve as a vehicle for conveying what he had to say; because those conventions were no longer his media, he had to discover new norms, new ways to use physical materials to make pictorial sense.

Continuous discovery is required because, in the grip of the modernist moment (which is the continuous present, whether recognized or not), we no longer in advance what counts as painting and what doesn’t count. And if the art of painting is to continue, then it is up to the individual artist to find out what is required to make something that will count as an instance of his or her art – to discover and establish, as if for the first time, what is essential to the art in each particular instance of that art.[iv]

Noland and the Issue of Shape

Like his friend Morris Louis, Noland worked with thinned acrylic paint stained into unsized and unprimed canvas. From the viewer’s perspective, staining (as opposed to covering or applying) tends to dissolve the distinction between color and surface (corresponding roughly to the distinction between figure and ground in traditional painting). To that extent, the surface is dematerialized and color is freed from tactile connotations associated with figuration. Paraphrasing a remark by Stanley Cavell[v], the surface of a color-stain painting by Louis or Noland or Olitski is not colored the way that a wall or cabinet is colored but as a blade of grass or soil is colored. And that implies that the canvas into which color is stained no longer functions as its support – or rather, while it remains an undeniable and obvious fact that the canvas is, after all, a literal support, this fact is somehow suspended in our experience of the painting, so that the color is simply there. The manner in which color appears in a Noland painting compels us, as Michael Fried wrote about a sculpture by Anthony Caro[vi], to believe what we see rather than what we know, and in so doing allows color to be experienced as a modality of being for which there is no parallel in the world (because in our world color exists only as a quality of objects).

However, by the time of Noland’s breakthrough, the dematerialization of surface by way of illusive coloredness was not enough by itself relieve the pressure of objecthood, which re-asserts itself (in the work of Noland, Olitski and Stella) as the issue of the shape, first of all the literal shape of the support. Insofar as the picture’s literal shape is taken for granted, it tends to be seen as an exterior limit that (as it were) marks off the picture from other objects – objects that are of the same basic ontological status. In other words, to the extent they are permitted to function as a limit, the picture’s literal edges establish an inside/outside structure, which outlines an enclosure within which objects can be inserted. And since enclosures are containers and containers are objects, the painting itself risks being experienced as an object, a thing in the world like any other. It was for this reason – to neutralize the threat of objecthood – that modernist painters were compelled to make pictures that can be said to consist in (apart from their color) the establishment of a more or less salient relationship between the depicted shape “within” the picture and literal shape of the support.[vii]

Kenneth Noland, “Trans Shift”, 1964, acrylic resin on canvas, 100 x 113.5 inches (254 x 288.3 cm), Art Estate of Kenneth Noland/Licensed by VAGA, New York, N.Y.

The significance of abstraction emerges out of the pressure exerted by objecthood on picture-making in the modernist situation. Properly understood, abstraction is always more an aspiration than a settled achievement because the contrary of the abstract is not the figurative but the literal. Literalness – the literal existence of the art work as an object – is never defeated or even evaded one and for all. To succeed as a painting, the modernist picture must everywhere (at every point on its surface) confront and (so to speak) neutralize the inescapable fact of its literal existence as an object defined by its physical limits. By “neutralize” I do not mean “deny” but rather counter (without denying) the inevitable tendency of those physical limits to be seen as a kind of container within which objects may appear. Countering that tendency means that depicted shape must somehow acknowledge the shape of the support. (In general, acknowledgment involves the discovery – for oneself and for another – of something we cannot fail to know; to acknowledge something (e.g., “I realize that I did wrong”) is not to impart new information but to reveal oneself, to make oneself present to another. We might say that in acknowledging, I confront and neutralize the literal fact of my own separateness from another; whether or not my initial isolation is overcome depends on the other’s responsiveness to my acknowledgment, which may be accepted or rejected.) Absent such an acknowledgement, the physical limits of the painting tend to be taken for granted as the human body is taken for granted when it is not seen as pervasively and at every moment expressive of (rather than a receptacle for) the human soul.

This last point bears emphasis because the formal simplicity of Noland’s motifs can easily mask what I believe is the intensely personal nature of his artistic aspirations. At a time when the continued viability of the art of painting as such was at stake in the undertaking of each ambitious work, the mere possibility that the work may be seen as an (literal) object was enough – given the inherent precariousness of the modernist enterprise – to preclude its being experienced as a painting at all, thus condemning the work to the artistic irrelevance of mere decoration or design for example. Under this kind of unrelenting pressure, the most successful modernist paintings, notwithstanding the formal simplicity of their design (what could be simpler than concentric circles or contiguous V-shapes or stripes?), demand to be seen as intensely passionate expressions of feeling – but feeling rendered abstract, as if the works are less “about” any particular emotion than the capacity to express feeling at all in an age characterized by the mass production of ersatz emotion packaged as ubiquitous imagery converging in a globalized marketing strategy.

Discovery: Constraint and Freedom

In this section, I propose to delve a little deeper into what it means to say that Noland “discovered” the center of the canvas. In his 1966 essay, “Shape as Form: Frank Stella’s Irregular Polygons”, Michael Fried wrote:

“[Noland’s] initial breakthrough to major achievement in the late 1950s came when he began to locate the center of concentric or radiating motifs at the exact center of square canvases. This related depicted shape to literal shape through a shared focus of symmetry. Whether or not Noland recognized that that was the significance of centering his rings and armatures of color is less important than that he experienced the centering itself as a discovery: a constraint in whose necessity he could believe, and in submission to which his magnificent gifts as a colorist were liberated.”[viii]

In a footnote composed several years later, Fried wrote that Stella and Noland did not simply “decide” to base their paintings on the literal size and shape of the canvas; rather:

“…the sense of something having been decided for him vibrates in Noland’s remark that, after making accomplished but finally derivative paintings for several years, he broke through to what he had been after all along when he ‘discovered the center’ of the canvas….He does not speak of having decided to do this, though there may be sense in saying that he must have done so: perhaps the sense there is in saying that the center was there before it was discovered. What Noland found when he discovered the center of the canvas was nothing less than how to make paintings in whose quality and significance he could believe, and this was not something he can be said to have had a choice about. We are speaking here of modernist painting as a special kind of cognitive enterprise, one whose success, in fact whose existence, depends on the discovery of conventions capable of eliciting conviction – or at least of dissolving certain kinds of doubt. (What at any moment those conventions are is in large matter a function of what they have been.) It is above all the nakedness of that dependence – the immediacy as well as the depth of the need for such a discovery – that distinguishes modernist painting from the traditional painting of the past.”[ix]

Kenneth Noland, “Spring Cool”, 1962, acrylic resin on canvas 96 x 96 inches, courtesy Harry N. Abrams, Inc., New York, N.Y.

The center was always there – in the sense that any limited expanse of canvas of a specific size and shape necessarily has a geometric center. But that fact – that every stretch of canvas in existence including every painting that has ever been made – was just that, a fact. With the breakthrough paintings of 1958, the center for the first time became something achieved rather than given; it became a bearer of pictorial significance. And it became the bearer of pictorial significance when it was made to function as a norm or convention by which forms located “inside” the picture’s physical limits could explicitly relate to the actual shape formed by those limits in ways that would declare and affirm picture’s identity as painting, notwithstanding its literal existence as an object in the world.

According to Fried, Noland’s discovery was in one sense a matter of the artist’s decision and in another sense not. In the late 1950s, Noland “decided” to make paintings that consist of concentric rings of color radiating out from the exact center of the canvas. This specific way of organizing color on a flat surface did not force itself on Noland any more than did his subsequent way of anchoring contiguous bands of V-shaped color from the upper left and right corners of the canvas beginning in 1962, or a few years later, his use of narrow vertically oriented diamond and horizontally extended rectangle formats. These were all what we might call personal decisions, choices made by the artist, and each of them revealed a new medium by which Noland’s personal feelings and aspirations could be expressed in pictorial terms.

But none of these ways of organizing bands of color on a flat surface amounted to a “medium” for the expression of Noland’s feelings, intentions or aspirations in the absence of the art of painting. What was not a matter of decision, what was not up to Noland (or anyone else) to decide, was whether or not this particular arrangement of colors on a flat surface is accepted as a painting. In the modernist predicament, what would count or not count as a painting is a matter of conviction, and we do not decide what convinces us (or not). We no more decide what is convincing than we decide whether a particular human action or expression makes sense (i.e., has a point) to another, and why. We are always yet to discover the source and strength of our convictions.

This observation gets at the significance of seriality in modernist painting. If in the modernist situation each work must discover anew those norms that are at the present moment essential to its being experienced as a painting, then those norms must be capable of generating multiple instances – a series of instances. Furthermore, those norms must be entirely manifest in each instance of the series. Each of its features or qualities down to the last detail is essential to its being the picture it is – any alteration of any element would not so much change the picture as create an entirely different picture. (For example, Noland’s discovery of the center of the canvas was the discovery of the center as a medium of painting, capable of generating a series of instances each of which is a complete or absolute realization of that medium. To imagine a different color for any of the concentric rings in an early Noland would be to imagine a different instance of the concentric ring series. By contrast, to imagine the concentric rings displaced from the exact center of the picture would be to imagine something outside of the series and for that reason, artistically incoherent.)

The sense in which each instance of a series is an absolute realization of the norm it discovers accounts for what I think of as the unprecedented way in which modernist paintings, and Noland’s in particular, face the viewer. The picture faces the viewer unconditionally because it is totally there – everything there is to see is entirely manifest and everything manifest is absolutely essential. Far from opening onto an immaterial void and leading us into an imagination of absent nature, the picture opens instead into the viewer’s space, inviting us to occupy our position before nature and contemplate the meaning of our absence from it.

Modernism Today: Fried on Charles Ray

Michael Fried’s career as an “evaluative” critic of contemporary art ended in the early 1970s when it became clear that the high modernist art he advocated has been eclipsed by post-modernism and its various permutations. Recently however, he has tentatively re-entered the arena, notwithstanding the fact that the artistic landscape (including the relevance if not the very possibility of evaluative criticism) has changed radically and perhaps irrevocably. In 2006, Fried published an excellent book on the work of several contemporary “art photographers” and 2011 saw the appearance of Four Honest Outlaws featuring essays on. four contemporary artists – video artist and photographer Anri Sala, sculptor Charles Ray, painter Joseph Marioni, and video artist and intervener in movies Douglas Gordon. Fried attempt to show how their respective projects are best understood as engaging in a variety of ways with some of the core themes and issues associated with the high modernism of the 1960s, and indeed with its prehistory in French painting and art criticism from Diderot on.

In my view, Fried’s project in Four Honest Outlaws is only a mixed success, and its flaws reflect not so much a decline in the author’s critical powers as the failure of the works under consideration to bear up to the standards of quality and value manifested in the work of artists like Kenneth Noland 50 years earlier. To demonstrate this point, I will close this essay with a look at Fried’s discussion of intentionality in Charles Ray’s work, a discussion that indirectly evokes some of the key concepts at work in Fried’s interpretation of Noland’s remark about discovering the center of the canvas. At the outset I will confess that although I have seen only one of Ray’s sculptures in person (Boy with Frog at the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles); however based on my viewing of Ray’s body of work in photographic reproduction I find that I do not share Fried’s admiration for this work. The remarks that follow comprise an attempt to come to terms with this fact of my own experience.

Ray’s project involves something like the replication of objects found in the world – except that the Ray’s versions can be said to replace the natural object, although at an ontological rather than a literal level. A sculpture by Ray does not imitate the natural object but reproduces it, so that while the reproduced object resembles the natural object, it is infused with and everywhere marked by the artist’s intentions. Fried finds a parallel with the processes involved in making Thomas Demand’s photographs. Briefly, Demand reconstructs in colored cardboard life-size models based on media images of actual rooms or other scenes in which something notorious or otherwise newsworthy has occurred. The reconstructions are then photographed in large scale. According to Fried (emphasis added), Demand’s project is to “choose scenes of places that one expects to be filled with historical traces of one sort or another and, by remaking them … to produce photographs that are saturated with traces of nothing other than his own artistic intentions – not just the general intention to reproduce some scene but the specific intentions involved in remaking it at every point …”[x]

Charles Ray’s Hinoki is a carved reproduction of a 32 foot log that Ray encountered one day while walking in the woods on the coast of California.

Ray cut the log into sections and transported the sections back to his Los Angeles studio. “Silicone molds were taken and a fiberglass version of the log was reconstructed. This was sent to Osaka, Japan, where master woodworker Yuboku Mukoyoshi and his apprentices carved my vision into reality using Japanese cypress (hinoki). I was drawn to the woodworkers because of their tradition of copying work that is beyond restoration.”[xi]

Fried’s discussion focuses on the densely carved surface of the piece: “…what is most compelling about the surface is the extent to which the viewer perceives literally everything that has been done to it – every join, gouge, cut, or hole, every smoothed patch or area, every tiny curl or remnant of wood shaving, in short every mark or trace of making, however large or minute – as a signifier or, better, a carrier of artistic intention.”[xii] In Hinoki, artistic intention is not so much present in as it is signified by carved marks, more precisely, marks of carving at every point on the extensive surface of this very large sculpture.

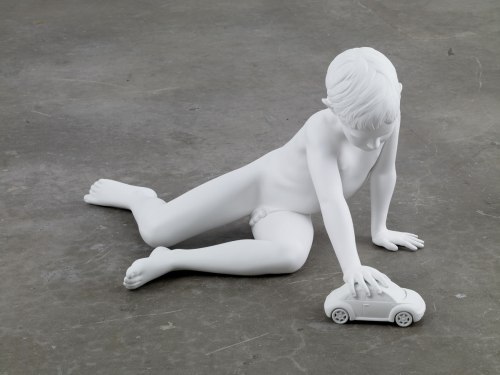

Compare this with Fried’s remarks on how “artistic intention” manifests itself in Hinoki with his comment on another sculpture by Ray called The New Beetle.

Whereas the surface of Hinoki is literally marked by signs of intentionality (in the marks left by the carvers’ tools), the surface of The New Beetle could not be more anonymous; that surface is composed of smooth steel painted uniformly white, apparently unmarked by any human touch. Nonetheless, The New Beetle is every bit as densely saturated with artistic intention as is Hinoki, according to Michael Fried. The pervasiveness of intentionality is demonstrated by the extent to which the long and complicated process of making the piece was dominated or dictated by the artist himself, who personally supervised every detail and aspect of the process. Ray began by photographing a four-year old boy, measuring various body lengths; a “figurative sculptor” was hired to create a clay figure, after which “Ray’s assistants took over.” After a year or two of investigating children’s proportions relative to age, Ray cast the clay, transported the cast to San Diego where another professional sculptor corrected the anatomy, etc., resulting in new molds, casting in stainless steel and assemblage at a fabrication factory. Fried describes all of this “so as to spell out some portion of the long and complex series of decisions, operations, delegations, and reflections – of intentions and their modifications – by virtue of which The New Beetle, for all its seeming simplicity, came into existence.”[xiii] While intentionality visibly saturates the visible surface of Hinoki (in the literal marks left by a team of wood carvers), the intentionality of The New Beetle is located elsewhere than in what we see when looking at the sculpture. It is found not in the work itself but in what we know about the artist’s pervasive control over every detail involved in the process of constructing the piece.

Fried compares the intentionality is manifested in Hinoki and in The New Beetle to that found in sculptures by Anthony Caro. Fried finds that the insistence of intentionality in sculptures by Ray and by Caro distinguishes their work from the “indeterminacy” found in Minimalist objects.[xiv] Whereas a Minimalist object is simply there, a more or less featureless thing in all of its opacity and inscrutability, a sculpture by Ray or Caro only exists (literally, so to speak) by virtue of its human significance, the intentionality embodied in it. I find Fried’s attempt to use the concept of intentionality as the basis for a parallel between Ray’s and Caro’s work to be singularly unpersuasive.

My being unpersuaded is based on Fried’s own earlier writings (and my way of seeing art, which has largely been formed by study of Fried’s writing), for example, when he observed that significance in Caro’s work inheres not in the identity of the materials that are used to construct a sculpture (girders, I-beams, steel sheets, etc.) or in its overall form, but in their utterly specific placement of individual elements and mutual inflection. “Everything in Caro’s art that is worth looking at – except the color – is in its syntax.”[xv] This observation led Fried to the insight that what we find in a work by Caro are not specific intentions but the always precarious capacity of human beings to realize intentions in the world generally. Caro’s sculptures “defeat, or allay, objecthood by imitating not gestures exactly but the efficacy of gesture … as though Caro’s sculptures essentialize meaningfulness as such – as though the possibility of meaning what we say and do alone makes his sculpture possible.”[xvi]

These or similar observations could not sensibly be made about a sculpture by Charles Ray – which, in comparison with a self-contained Caro, invariably strikes one as pointing beyond itself. At one point Fried does acknowledge a significant difference, but fails to assess its significance: while a Ray sculpture “thematizes” intention, a work by Caro does not.[xvii] But this is a distinction that makes a world of difference.

We might rephrase the point by distinguishing between signifying intentionality (Ray) and expressing intentionality (Caro). (A signified intention is always specific, whereas intentionality expressed affirms a human capacity, the capacity of human beings to effectuate intentions by means of action.) In Caro’s work, intentionality – the human capacity to mean what we say and do – is conveyed to the extent that one is convinced by the evidence of one’s eyes notwithstanding what one knows about the work; as Fried wrote concerning Caro’s 1967 sculpture called Prairie: “More emphatically than any previous sculpture by Caro, Prairie compels us to believe what we see rather than what we know, to accept the witness of the senses against the constructions of the mind.”[xviii] If a Caro piece compels us to believe what we see rather than what we know, what we see in a Ray piece makes sense only in light of what we know – for example, that the surface of Hinoki is marked by the craftsmanship of a team of expert wood carvers over years of collective work under the careful and detailed supervision of Charles Ray, and that Charles Ray is personally and specifically responsible for each of the myriad decisions and delegations and processes that produced the object called “The New Beetle.” I would like to say that in Ray’s works intentionality is conveyed not so much by visual facts (facts known by way of our experience of the works in question) as by facts that account for the visual appearance of the works – “account for” in the way an efficient cause accounts for its effect. Hinoki and The New Beetle may be read as allegories of intention, while Prairie may be seen as an embodiment of intentionality as such. (As an allegory of intentionality, Hinoki seems closer in spirit to a Minimalist object such as Tony Smith’s Die (counter-posed to Hinoki in Fried’s essay) than to Prairie. While Die is entirely featureless and in that sense “indeterminate”, its specific placement (in a gallery space for instance) invests the piece with intentionality – specifically, the intention that it be experienced as marginally or ironically “art” notwithstanding its lacking any features or qualities that would distinguish it from any other object of similar size, shape and dimensions. Die demands to be seen as an allegory or “signifier” of the death of art.)

This leads to the heart of the matter and back to Kenneth Noland. There is nothing in Charles Ray’s art (or indeed in the work of any of the artists discussed in Four Honest Outlaws) that corresponds to Noland’s “discovery” of the center of the canvas, and there is nothing in Fried’s discussion of Ray’s art that corresponds to the concept of “conviction” and the crucial role it assumes in Fried’s evaluative art criticism.

Regarding the first point, recall that Noland’s discovery was a discovery of specific constraints – norms or conventions (centeredness in relation to the square format) to which had to submit as organizing principles in order that color applied to canvas could be experienced as a painting. If Noland’s intention was to make pictures that made color present to the beholder in ways that were unprecedented, he had to discover and accept certain norms that would permit his intention to be realized in ways that would establish continuity with works of the pre-modernist past whose quality and value were not in doubt.

In Ray’s work, intention is not expressed by or through the discovery of constraints that are experienced as liberating. On the contrary, as characterized by Fried, intentionality is manifested as the artist’s pervasive, saturating, directing control – over materials, processes, delegation of tasks to collaborators and experts, decision-making, craft and methods used in bringing the work into existence. Control implies realization of desire in the absence of constraint. But desires are realized in the absence of constraint only in the realm of fantasy, and fantasies are essentially private. This accounts for the Surrealist aura of uncanniness that surrounds many of Ray’s pieces – for example, images of himself in sculptures like Oh Charley, Charley, Charley…. (1992) and Puzzle Bottle (1995), of children (Family Romance (1993) and of children’s toys (Father Figure (2007)).

Regarding the second point, the term “conviction” refers to our relationship to modernist works that exist as paintings (or as sculptures, etc.) in the absence of settled conventions or norms that would guarantee their identity as paintings or sculptures. Such works are said to “compel conviction” by virtue of their discovery of new conventions that allow us to “believe what we see rather than what we know, to accept the witness of the senses against the constructions of the mind” – works that force us to the realization that we don’t really know and never really knew why or how anything counts as a painting or a sculpture. The concept of “conviction” in Fried’s early writing instructs us to trust in the primacy of our experience (of quality and value) rather than rely on things we think we know.

It is therefore no accident that the concept of conviction is absent from Fried’s discussion of Charles Ray and any of the other artists (like Thomas Demand) whose works seek to replace objects or events or situations found in the world. Such works seek to re-create the world in our image or according to our wishes, and to that extent they fail to reveal the world – our world, in which desires are realized only by taking risks and in which every victory exacts a cost.

[i] Reported by Michael Fried in “Three American Painters: Kenneth Noland, Jules Olitski and Frank Stella”, in Michael Fried, Art and Objecthood (Chicago and London 1998), p. 239.

[ii] “After Abstract Expressionism”, in Clement Greenberg, Modernism with a Vengeance 1957-1969, vol. 4 of The Collected Essays and Criticism, ed. John O’Brian (Chicago, 1993), pp. 131-32.

[iii] Id., p. 132.

[iv] In “A Matter of Meaning It” Cavell writes (concerning Anthony Caro): “The problem is that I am, so to speak, stuck with the knowledge that this is sculpture, in the same sense that any object is. The problem is that I no longer know what sculpture is, why I call any object, the most central or traditional, a piece of sculpture. How can objects made this way elicit the experience I had thought confined to objects made so differently? And that this is a matter of experience is what needs constant attention; nothing more, but nothing less, than that.” Stanley Cavell, Must We Mean What We Say? (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1969), p. 218.

[v] Cavell, op. cit., p. 217.

[vi] “Two Sculptures by Anthony Caro” in Fried, op cit., p. 183.

[vii] “Shape as Form: Frank Stella’s Irregular Polygons,” in Fried, op. cit., pp. 77 – 99.

[viii] Id., p. 80 (emphasis added).

[ix] “Jules Olitski”, in Fried, op. cit., p. 146 (emphasis added).

[x] Michael Fried, Four Honest Outlaws: Sala, Ray, Marioni, Gordon (New Haven and London, 2011), p. 102.

[xi] Statement of Charles Ray, found at http://www.artic.edu/aic/collections/artwork/189207.

[xii] Four Honest Outlaws, p. 102 (emphasis added).

[xiii] Id., p. 113.

[xiv] Id., p. 103.

[xv] “Anthony Caro”, in Michael Fried, Art and Objecthood, p. 273.

[xvi] “Art and Objecthood”, in Michael Fried, Art and Objecthood, p. 162.

[xvii] Id.

[xviii] “Two Sculptures by Anthony Caro”, in Michael Fried, Art and Objecthood, p. 183.

First a personal thank you for this really helpful essay. I think I now have finally understood at least one version of what modernism is.

What I don´t understand is why it should be necessary, even within the “modernist moment”, for artists to continually discover new conventions when some individual combination of existing conventions might also be satisfactory as a means of expression. From the viewpoint of an art historian (and for the possibilities available to future artists), the discovery of a new convention is obviously of great interest, but from the viewpoint of artistic communication it is surely irrelevant which conventions the artist has found most appropriate. If the primary requirements for an artwork are to communicate and “convince”, then it must be possible to work within a personal choice of (individually inessential,) existing conventions without automatically becoming stale and derivative (?).

And are all conventions equally fit for purpose? Kenneth Noland´s discovery of the centre may have a neat and intellectually satisfying justification in terms of acknowledging the shape of the canvas, and the novelty of it may have liberated him from unwanted external influences. It made him free to concentrate, beautifully, on colour, but on the other hand there are surely conventions within the painting tradition which better reflect what it is to be human. Why then (apart from innovation) turn to concentric circles? Aren´t some of these “discoveries” to a certain extent just changing the rules to simplify the task at hand or to confer an easily-won originality? Couldn´t it sometimes be a greater accomplishment to achieve a new and individual expression within a well-used but (for the transport of human content) more effective framework of existing conventions?

Art must continually renew itself but it is not an originality contest. For me (and I think I am agreeing here with something that you have already said) it is the common struggle to keep alive that quality – humanity, spirituality, the real, “right-brain thinking”, non-objecthood, “that whereof we must be silent” – it doesn´t really matter how we allude to it – which connects us to each other and to the world, in the face of the indispensable but overly dominant, language-based thinking that serves science, technology, power and survival.

LikeLike

Hello Richard – thank you for your comment. As I understand it, you are saying that a modernist artist need not “discover new conventions” in order to make viable art. For example, “an individual combination of existing conventions” might do the job, which is to convey artistic significance to the viewer in ways that are emotionally, spiritually and intellectually satisfying.

I don’t disagree with that point. In fact, I think Kenneth Noland provides a good example because Noland’s “discovering the center” of the canvas was in fact a way of organizing (in a new way) inherited conventions of painting that would give those conventions a new life so to speak. For example, the literal shape and size of a picture were conventions; likewise, the use of color has always been a convention used in the making of paintings; and symmetry has always been a convention in Western picture-making. But I think the problem for Noland and others at the end of the 1950s was that existing conventions could no longer be relied upon or taken for granted in the same way that they had been in previous painting. I think that for an artist like Noland, the innovations of impressionism, Matisse and abstract expressionism (especially Pollock as interpreted by Frankenthaler) had demonstrated that conventional ways of using shape, color and symmetry had exhausted themselves so that the art of painting had to explicitly acknowledge the conventionality of existing norms in order to survive and create a future. It was no longer known or knowable what conventions could be still be used to make something that would count as a painting (as opposed to an object of some kind). At that point, one could either set one’s task as finding out would could count, or as dispensing with the art of painting altogether (as I think happened with Pop art and then minimalism and then post-modernism) in favor of “theory.”

Noland chose the former route. His use of stained color (following Pollock, Frankenthaler and Louis) liberated color from the norm of applied color – the idea that a color must manifest itself in experience as A COLORED OBJECT. I think that Noland found this idea to be implicit in the work of Matisse and Paul Klee (and probably others like Newman). And Noland found that by organizing his pictures around concentric rings of color radiating from the exact center, he could articulate symmetry in ways that would establish an explicit relationship between the painted areas within the picture and its literal edges – so that those edges could be experienced not as literal (and therefore more or less arbitrary) facts but as constituting shape as a bearer of artistic meaning.

In short, I believe that Noland’s aspirations as a painter were fundamentally conservative inasmuch as he felt compelled to preserve values that he found in the art of the past that he most admired; and the only way those values could be preserved was by altering inherited conventions, by organizing them in new ways.

But this was the modernist moment, and it has passed, as I try to show in the second part of the essay using Charles Ray as an example.

LikeLike

Hi Carl, and thanks again.

My objection to concentric circles was that the convention determines too much of the artwork, leaving only a very few decisions to provide the human content. I´m not too well acquainted with the details of Noland´s painting but let´s take a straw-man Noland with hard edges, even, unmodulated colour and perfect symmetry. For this Noland there are only about 10-20 decisions per painting (colour and width of the circles). Compare that to (say) a late de Kooning painting, which might be simple in appearance but is very much less determined by its conventions. Here there are thousands of decisions – conscious and unconscious, active and passive – concerning not only the composition but also every centimetre of the colour boundaries and every square centimetre of surface, minutely inspected to ensure the integrated surface and coherent pictorial space that his conventions consciously or unconsciously demanded.

Or consider the hundreds or maybe thousands of decisions involved in “acknowledging the frame” for Titian, Constable, Cezanne, Pollock etc. etc. For Noland it is one single decision, taken at the outset, to adopt concentric circles.

That said, I am beginning to think that this criticism is misplaced. I can´t formulate this very well, but it seems to me that there are artworks that say “look here” and artworks that say “look there”. A “look here” artwork is the trace or witness of an instance of being (the artist). Our commonest everyday experience of “non-objecthood” is the encounter with other people, their non-objecthood culturally cemented in human rights and in the incorrigibility of first-person statements about thoughts and feelings. A “look here” artwork provides a proximated encounter, removed from the flow of time and therefore allowing for more clarity in the making and more contemplation in the viewing. This kind of artwork benefits from as much decision-making / human input as possible.

A “look there” artwork creates a situation in which the viewer becomes more aware of their own perception and being. The way you describe Anthony Caro´s “Prairie” suggests that this is primarily a “look there” artwork. Another obvious example would be the work of Robert Irwin. This kind of artwork doesn´t need so much human content because it doesn´t contain or bear witness to an instance of being but directs attention to the viewer´s own being.

I´m sure both aspects can be present in differing proportions the same work. The old masters had their “look there” element in the integrated-surface-plus-pictorial-space convention (it still works for me).

Noland with his immaterial colour is presumably weighted towards the “look there” side. The lacking-in-human-content argument would then be irrelevant.

LikeLiked by 1 person