It is somewhat taken for granted that the art of painting allows us to engage intimately with the work of another’s hand and eye. Some might even suggest through the marks and traces locked in the gestures and dispersal of paint on canvas, we are witness to some special marriage of spirit and matter. As makers and viewers of paintings, artists have always exploited these contrary sensations of the public and private at work in the mind during the act of looking. Are you a voyeur or co-conspirator? Lover or fellow member of the dispossessed? Intrigue, desire for narrative and the visual unravelling of secrets all elicit deep fascination, bound up as they are in the articulation of the medium itself. Figurative painting’s power, to a lesser or greater degree, hinges on the frisson of implied intimacy or its denial. But what about abstract painting? It was these sorts of questions that kept coming to mind as I walked round Power Stations, the show of mostly large scale abstract paintings by John Hoyland spanning the period 1964 to the very early 80s.

The tension between the public and private roles of art intensified in the debates around abstract painting in the post-war period. In fact there is something faintly absurd about the size of Hoyland’s paintings in at least the first 4 rooms of the Newport St. gallery. They portend to the dimensions of great history paintings, yet give us such little detail or sniff of a narrative of any kind. ‘Handling’ is reduced to a minimum, either locked into a deep staining of the canvas or in the masking-off of flat, high-keyed ‘blocks’ of colour. Their size is institutional, municipal, dare I say it, communal. Overtly public in their forthrightness and seeming simplicity, they ask to be shared as visual experiences by the many rather than owned by the one or the very few (unless you are a millionaire artist-come-collector-come-property-developer with mansions of large dimensions – but more on that later).

The mural sized paintings that became so familiar with the rise of Abstract Expressionism are an obvious early influence on Hoyland’s mature work. It’s well known that Hoyland spent much time in the US seeking out, learning from and challenging the American trial-blazers of abstraction and their ‘colour field’ inheritors. (And he was not the only one.) But Hoyland’s work first appeared on the British art scene in dialogue with artists experimenting with colour, size and scale but with very different ambitions for their work than those of the dominant Americans. For sure, we can see the direct influence of both Rothko and Newman. But these American artists had invited criticism for their scaled up intimations of ‘tragedy’ or ‘heroism’ that could so easily degenerate into pretentious and high minded procrastination. And many artists were questioning this almost maniacal obsession with the artist’s own subjectivity and ‘vision’. Maybe a sentimental haze has descended over many of the ideas around in the 50s and early 60s and the general optimism of what has been termed the ‘post-war consensus’ in this country. Hoyland, like many other young British artists at this time, benefited from that ever so slight relaxation in the ‘entry rules’ to a snobbish, uptight, class bound, nepotistic art world. There were other difficult ideas in the air too. Art, it was said, just like higher education, should be for everyone; these ideas would become the basis for the ensuing battles/confusions between cultural democracy and the democratisation of culture over the coming decades. In fact, from this point onwards, what started as a fissure in the side of an ailing cultural establishment turns into an ever widening gap between the reality of new rapid cultural change and what was taken for granted by the hopelessly backward looking parochial art world which was then so quickly replaced by the self serving rhetoric of a transatlantic ‘high’ modernist art.

Hoyland’s 60s paintings remain on the cusp of these huge changes. We look back at them as through a dark prism from our own historical time and space. My contention is that by emphasising Hoyland’s connections to a transatlantic formalist kind of art we are denying his connection to another more critical and socially-engaged set of values at work in another strand of DNA locked in the fabric of this earlier work.

That different batch of DNA can be found in the work of Hoyland’s more immediate predecessors and contemporaries like Robyn Denny and Richard Smith and many others who made abstract art that looked toward modern architecture and design – combining these interests with a hard edged pop sensibility. Although seemingly austere in their simplicity and directness these British artists were investigating notions of play, improvisation and collaboration. Experimenting with the materials that make up the very fabric of the modern world, they were pushing at the limits of any given medium and loosening the grip of the individual artist’s ego. Compare this approach to the now well documented self-flagellation and paranoid resentment Rothko tortured himself with while working on the Seagram murals commission! Was Hoyland also trying to get away from ‘the great British landscape tradition’ and the more rustic-type lyricism at work in older artists like Heron and Lanyon? This new generation of British artists began seeing painting as a place for devising a dialogue between artist and viewer by combining pictorial space and the viewer’s own sense of lived space. This was achieved by experimenting with size and scale that echo bodily stance and the architectural proportions of the new urban environment. Colour tended toward close-toned and high keyed relations that would suggest optical throbs and undulations in large fields of intense contrasting or competing hues. The artist’s personal ‘touch’ or handwriting became secondary to this end.

These artists wanted to engage the eye in constant readjustments between shape and surface – heightening awareness of the complex circuitry of perception constantly reconnecting the eye to the mind and the body. From this perspective I found the earlier works in the first four rooms of this exhibition far more exciting than the later paintings in the last two rooms. These later works feel somehow backward looking, no matter how locked in and finished they are. I love ‘craft’ and the highly considered – but it is interesting to note the shift of emphasis in the later works such as Longspeak 18.4.79 to a smaller scaled, highly worked and more complex interpenetration of colour relations. It’s well known that paint handling can be the first thing to suffer when working on large-scale canvases. While wanting to court visual impact, gestural attack so easily becomes overblown and prone to theatricality. 28.2.71 and other works in the penultimate room suffer here, even if the convulsive handling and fleshy tones are a fascinating combination. Conversely though, painting over large areas of canvas in one colour can create deadening and monotonous surfaces. Artists working with the ‘field’ approach dealt with this by melting gesture into the stain and building up many and highly complex liquid thin layers of different colours in the hope of deepening colour intensities and contrasts in one large surface. I think 9.11.68 and 29.11.66 seem much more daring in this respect.

By the middle of the 70s there had been some kind of burn-out in the visual possibilities of the ‘high’ modernist trajectory. In terms of art history it is often asserted that Hoyland’s intention was to combine a supposedly American ambition for painting (which is often mentioned in terms of the size and scale of the mural and the freedom of the individual) with the never quite abstract easel painting found in the more northern European sensibilities of de Stael or the exiled German in America, Hofmann. But did this attempted transatlantic synthesis take Hoyland beyond that burn out? So where next then for abstract painting? One way forward was to go backwards – to retreat from the public dialogical role of art, to reassert the lyrical impetus in painting that sits so cosily with the idea of the artist’s private vision. There was also, at this time in Britain, a burn-out in the optimism created by post-war socialist governments and the satisfactions promised by the rise of the consumer society. By the 1980s this went hand in hand with the rise of a new found conservatism (with a small and capital C) pronounced by the likes of Roger Scruton and Hilton Kramer and emboldened by a general rise of the Right in politics.

Here in the second decade of the 21st century, Hirst’s patronage of Hoyland’s art is intriguing. I mention this because what interests me is what historically separates them as artists. One seemed primed for success in an age of optimism and change; the other’s career was forged in a new epoch of cynicism and doubt about the edifying role of art and its new-found relationship with money. Our new world order is built on what seemed like the final victory of capitalism, the rapid demise of the Soviet Union and the rise of the new global free market economies. I think the implications of this generational shift from the post-war consensus to a neoliberal one are somehow evoked in this snapshot of Hoyland’s legacy caught here in Newport St.

My old Marxist teachers told me that by the early 80s institutions, galleries and exhibitions had become little more than the residue of the political and commercial machinations operating behind and/or maintaining the facade of what is taken for granted now as ‘the culture industry’. It could then go on to be argued that this is why so many artists turned away from that transatlantic kind of ‘high’ modernism and went on to scrutinise these machinations. They shifted their emphasis from the work itself to analysing the way we are ‘allowed’ to perceive ‘art’ both in its making and in its dissemination. But all that wasn’t enough for some, even of the Left. Some couldn’t reduce art to a set of ideological imperatives or critiques – but nor could they let their belief in the communicative power of abstract art be lost in a self-referential hall of mirrors or ever decreasing circles of pastiche and irony. It was Hoyland who, amongst a few others, presented a benchmark, a standard of commitment to abstract painting.

Conceptualism has failed to fully transform our experience of art. It has been utterly absorbed by the machine it set out to question. Abstract painting still retains deeply subversive tendencies because it undermines the power of language to control meaning. But are these tendencies born of the thoroughly private and personal vision of the artist as individual? No, I don’t think they are. Is Hoyland’s importance as an artist locked in the overt handling, the indexical mark-making that dominate his later paintings? No, I don’t think it is. Paintings have an uncanny habit of leaking alternative and disruptive meanings or knocking our sense of historical time and place off kilter. They have the ability to somehow unravel the tightly wound power of dominant discourses on ‘art’ instead of simply being ciphers that re-enforce them. Some might argue that this subversive ambition is too big an ask of painters painting now – but I guess that this is what I wanted and hoped for from this show. I didn’t get that jolt from the later more crafted ‘painterly’ paintings that seem so wrapped up in their own surfaces, handling and historicism though. I got it from the earlier overtly open, public and declarative ones.

I like this piece and I think it is important to get Hoyland out of monolithic interpretations, but I’m not convinced by this ‘leaking alternative and disruptive meanings’. If you’re right about Hoyland and his links to the post war consensus then the paintings you like are not subversive, but rather reflect the dominant ideology at the time, it’s just an ideology that you happen to agree with.

LikeLike

For English abstract painters like Hoyland, making large paintings in the sixties was a popular option. Prompted by American precedents in Pop and Colour Field, it was a symptom of artistic ambition rather than hubris. Of course, there was the practical problem of where, except for the art gallery, to put works that couldn’t be accommodated in standard British domestic interiors. This is where architecture and ideology come in.

Large paintings are often classified as ‘Foyer’ art, meaning big-ticket items installed in the entrance halls of prestigious business buildings. However, the foyer was an interesting architectural innovation of the period. Like the church it combined public and corporate indoor space on a big scale. Though we might now think of such venues as expressions of commercial power, at the time these spaces seemed to offer an opportunity for abstract art because they were often plain, geometric and relatively neutral, ideologically speaking.

Placing large abstract paintings in these kinds of spaces was the specific aim of an exhibition at the Royal Academy in 1969 called Big Paintings for Public Places. It was supported by the Institute of Directors whose general adviser, Sir William Emrys Williams, wrote a short catalogue note. In it he stresses the potential aesthetic value of large paintings in an architectural environment, a new social space, ‘where people work or gather together.’

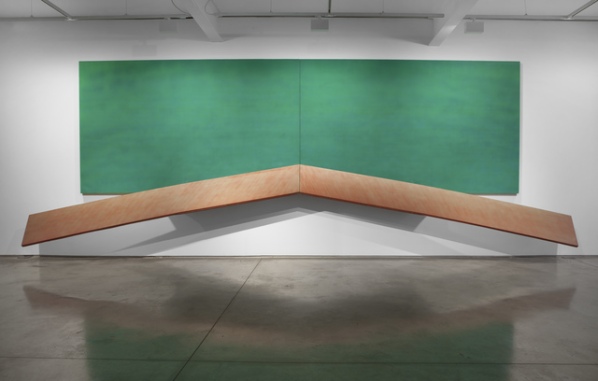

The 16 exhibitors included Basil Beattie, Sandra Blow and Noel Forster. I contributed a work that was 34 ft wide by 17 ft high. The central area of approximately 450 sq ft. was pale green. This was probably the largest area of one colour in a painting ever exhibited at the RA, or anywhere else, before or since.

Despite a reasonable amount of publicity nothing came of the initiative, and this may have been (arguably) for ideological reasons. Contrary to the usual narrative, it suggests that, in an English context, high modernist paintings may indeed have appeared as challenging corporate interests. Sir William, who was a prominent figure committed to widening access to the arts and education, and a socialist with a small ‘s’, obviously had a far more enlightened view of culture than other members of the Institute, or the business community.

LikeLiked by 3 people

The thoughts of Bunker on Hoyland were not raised by his perusal of the Hoyland show as claimed; they are prejudices Bunker brought with him to the show. He has been pushing this line for years, like Sysiphus, a large chip on sloping shoulders. “Denny did not seem interested in the idea of an artist’s private vision; that special “something” that can only be shared between suitably obsessed confidants, (Artschool based hierarchies and the dominant social class supporting them etc.) ……….it is the intense physical and mental experience of city living which must be attended to by the socially aware abstract artist. At the same time he (Denny) refused to pander to the individualistic nihilism or the cliches of an alienated soul (the basis of so many of Modernity’s most entrenched myths.) Instead, he embraced the new manifestations of a shared communal culture that the urban experience is uniquely placed to offer an artist.

The qualities and intentions attributed to Denny’s paintings, of an interactive dialogue between the observer’s perception of quotidian architectural space within which they meet the painting and the spatial illusions created by the paintings themselves — are actually qualities Denny had imbibed from Barnett Newman, in his paintings and his professed intentions (amongst other qualities) — and so, to denigrate Newman’s (and Rothko’s) as subjective, “private” visions is completely unwarranted, but it chimes with Bunker’s wish to portray “publicly engaged” art as somehow an advance on “high modernist” subjectivity.

This publicly engaged art, using materials , the stuff of the modern experience,etc. –has been flogged to death without producing any painting of lasting import –has been assimilated into the fabric of hack- modernist decor on our towns, tube stations, and the atria of corporate strongholds.

Painting does not belong in any of these spaces, because it requires contemplation, not to be hurried past on the way to the board meeting. What is so appealing about the urban environment,which consists largely of the detritus of failed projects in on-the-cheap bowdlerised versions of the modernist masters, that it should be the task of painting to engage with?.

LikeLike

Sorry. quotation marks should be added at close of the first paragraph.

LikeLike

It can be humble and unpresumptuous to reveal oneself in an intimate artwork, just as it can be humble and unpresumptuous to try to improve the visual quality of a public space.

Ego is a common enemy of both these approaches. In the former it can turn testimony into manipulation; in the latter it can turn enrichment into edification or even propaganda.

Something that could and should be an offering then becomes an imposition, which is nearly the opposite of art.

I don´t think either approach is immune to this.

LikeLike

I’m Afraid Bunker’s shtick contains a wealth of misapprehensions.

That the Middle classes , and indeed the upper classes are somehow not part of “communal culture”, whereas they form the biggest part of it, with their Rothko reproductions in the kitchen along with the fridge magnets.

That because an artist has left-leaning credentials, their abstractions are Ipso facto socially engaged.

That “communal culture” could care less about abstract art, whether hand crafted or self-a negating.

If you want communal culture, go to Disneyland, or the Big Bruuther Hauss.

That the suppression of overt “handling” is somehow less “subjective” or “private” than the expression of “touch”. What could be more subjective than the surfaces of Ad Reinhardt or Agnes Martin?

That the use of industrially produced materials, plastics, aluminium sheet, non-art papers, MDF. Etc, makes a work more “relevant” to today’s culture than paint on canvas. Look at what happened to Kenneth Noland’s pictures when he tried that!

That popular culture, communal culture is not as manipulated a product as any other aspect of late capitalism. If you want to sup with “communal culture” you maun tak a Lang spoon, (as Hoyland found to his cost ( and short term gain) when he palled up with Damian Hirst.

Can you appeal to communal culture and “subvert” it at the same time? And if you can, painting is just as likely to do it as any other form.

Mr Bunker is as full of inverted class snobbery as T.J.Clark, with his “upperclass ethos of aesthetic novelty”, but that’s another story.

I could go on, as there are many more, but enough already.

LikeLike

Whilst I tend to agree with you, Alan, about most of John B’s essay, a rather more important aspect of his “shtick”, as you call it, is the collage work he is producing, which, regardless of his motivations, theories and intentions, exhibits some of the most compelling 2-D abstract content around at the moment (as seen in his current show “Tribe” at Westminster Reference Library).

If you want to know what I mean by “abstract content”, Alan, go see.

Am I co-opting him for the cause? You’re damn right I am.

LikeLike

With respect,because I value John Bunkers work.However I found the lack of any intimate communion with individual works a bit alarming.It seems to me that Hoyland ,over and over again ,went for a particular kind of quality in a picture,Richness thru splendour,uplifting emotion close to the sung spiritual and a kind of grace through dignity.He didnt always acheive it but he nailed his colours to the mast on a daily basis.When he succeeds,the result is truly inspirational and there are enough of them over a lifetimes activety, to guarantee his deserved acclaim as a very good,possibly great artist indeed

LikeLiked by 1 person

It”s not until one sees such lousy pictures, that one can value the Americans that started it, artists in a different league altogether, it’s like comparing the Stuckists with the Fauves.

LikeLike

Each to his/her own Sandra.I feel sorry that so many people seem to have clouded vision when it come to looking.Painting should reflect a particular kind of joy at being alive.How it does that can be discussed at length using the perceptions of the individual viewer.However there is no doubt anyone going to Hoylands show looking for political critique would be wasting their time.Of course the work reflects the extraordinary perceptions of the artist ,in relation to civil liberties,and to that extent Hoyland is a student of Motherwell,his friend and mentor.If this is High Modernism then it has yet to be surplanted by any cynical re-evaluation,which has completely failed to provide any visual sustanance.The majority of recent abstract painting in england is completely meaningless ,to the degree in which it ignores its traditions..

LikeLiked by 1 person

‘The work reflects the extraordinary perceptions of the artist, in relation to civil libertiies’. ‘Civil liberties’? WTF are you on about? It’s PAINTING!!!!!!!!!!

LikeLike

There is no ‘elegy for the Spanish Republic’ in Motherwell’s pictures, nor is a red square anything to do with Russia and Communism, there is no societal connection between Malevich’s art and society.

LikeLike

I agree Sandra – or should I say Peter (Stott), for it is you, and I have no idea, nor do I wish to know, why you don’t comment under your own name (that’s your business, until such time as you get offensive, anyway). Your comment brings us full circle, back to the rather pointless contention that abstract art somehow embodies socialist ideals (or even some kind of idealism, as per Alan G) – see Charley’s essay from exactly one year ago. One year on, not a jot wiser? Maybe, maybe not. But there is nothing inherent in Hoyland’s painting to stop Donald Trump using it as a campaign banner, especially with all those vague aspirational virtues you list, Patrick. Better to speak of other things…

LikeLike

Sandra Sandentonair is less confrontational ;-), I’m thinking maybe Voda Vodova might be a good career name move, cos my name is mud! Maybe when the ‘transcendental imaging’ theory is more established…

Art is mysterious, abstract art particularly, there may be ‘something to it’, but one can’t just apply meaning, willy-nilly, just because there is ‘something to it’, certainly not social ideals.

LikeLike

…OK, I recognize the Bass red triangle, but there is no Bass Beer in that red triangle, nor is the beer made of it, it symbolizes the quasi-religious tradition of the maker and by further implication the guild of makers. That may contradict the opinion that art is not social, but if one were to think that a black square might bring about social cohesion, in spite of no information for social cohesion within it, then one might as well just support England, forget art and just look forward to the European Championships.

LikeLike

While we are on the subject of civil liberties,perhaps some form of censorship should be considered.I am happy to debate with Bunker or Gouk ,because their own work is as truly felt as their writing..Whether the argument is familiar or not is less important than the fact I know they are trying to make a contribution .Casual interference by others really denigrates the integrity of Ab Crit,which has been so important to the onward discussion of Abstraction..To the gulags with them ,never to return,if you want this discourse to continue.

LikeLike

Don’t include me in that diatribe, I’m a serious artist and a published art academic.

LikeLike

Sorry to take so long to get back to this thread.

All of us have our own shtick Alan, and I don’t think you have to be too much of a ‘neo’ ‘pseudo’ or ‘vulgar’ Marxist to sense the presence of the Rightist and very contemporary Roger Scruton pulling a few of your strings under all the bluster, musical analogies and mind boggling art historical references.

Thank you for taking the trouble to quote me at length from an essay I wrote for a small exhibition of Denny’s work mounted a couple of years back. That quote should be read in context though. It comes under a sub heading called ‘What If’ and goes on to briefly highlight other ideas that caught the imagination of artists in Britain besides Denny during this era. You are right about that chip but wrong about sloping shoulders. I think you need pretty broad ones to try and take the weight of complex circuitry connecting abstract art to the society in which it evolves. From this perspective I think you are wrong to suggest that Denny swallowed Newman and Rothko hook, line and sinker. Denny’s interests ranged from the impact of the Tintoretto murals in the Scuola di San Rocco to ‘game theory’ and the power of collective experiences gained from mass communications. On a relatively recent trip to Tate Britain, I entered a room of painting from the 50s (I think?). I saw a Denny painting called ironically enough ‘Home From Home’ (1959). I laughed out loud because it seemed so utterly out of place! What was striking was its strange alien like quality. The painting felt like a rupture, a break in the continuity found between Heron, Davie and Lanyon for instance, which only seem different from each other by degrees. On a later visit to reconsider my first reaction, the Denny had been replaced by Lanyon’s St Just painting. All felt normalised again, a continuity had been re- established. But I preferred the disruption caused by the Denny.

I guess I wanted to think about Hoyland in the context of this sort of disruption and the very contrary ideas we have about art in the 60s into the 70s. It has been entertaining to get your own take on it and after all it sounds as though people like David Sweet, Patrick Jones and your good self were in ‘the thick of it’.

It was also interesting seeing Robin’s cheeky tweet…. “@RobinGreenwood1: Surely there’s more to art than mere richness, splendour, uplifting emotion, spirituality, dignity and grace.” with the link to my article.

Well, on the contrary Robin, no way am I suggesting that these most venerable human qualilities should be ignored or degraded by my admittedly clumsy attempts at art criticism. But I think yes, there is far more to art than those particular qualities! There is something about the modernist spirit that takes such qualities to task, it’s that questioning spirit that makes these particular words sound tinny- like so much empty rhetoric. Modernism questions the use of such catchalls. These words turn so quickly to ignoble effigies, cartoons of self-aggrandisement. We are now hyper aware of the whiff of hypocracy when it comes to notions of high culture emanating from self serving heiraches whether they be of the old fuedal societies or the capitalist or totalitarian ones. Our critical faculties have been honed by Enlightenment thinking- but ultimately this thinking must turn on itself to scrutinise its own foundations. For better or worse, Modernism is part of this (in-part destructive) process. (Foundations dug in the money and power accrued from the slave trade, the industrial revolution and rampant almost psychopathic empire building of the west. Dug in the trenches of 2 world wars the rise of European fascist and communist dictatorships, the holocaust, the Gulags, the Stalinist ‘Terror’, the threat of nuclear war, Vietnam, the Cold War and on and on….. I guess to find solace in the great art of the past is one way through what is perceived as nihilist shtick- to find continuity between the ages locked in the act/craft of painting is one way of dealing with it. After all Marx did say ..

“Only through the objectively unfolded richness of people’s essential being is the richness of subjective human sensibility ( that is, a musical ear, an eye for the beauty of form- in short, senses capable of human gratification, senses that affirm themselves as essential powers of humanity) either cultivated or brought into being….. The forming of the five senses is a labour of the entire history of the world down to the present”.

The Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844.

Alan, in your recent contribution to Abcrit concerning T.J Clark, I liked very much your image of the student attempting to invoke the daemons of postmodern desire and power in that seminar. But I’ve had to put up with equally irritating pronouncements from students mired in so many other cliches of self obsessed romanticism- agitated highly repetitive charcoal drawings that are somehow capturing the ‘spirit’ of the sitter etc. Lets be clear- the cliches come from both sides of the cultural barricades. This clip of Eagleton and Scruton elaborates this point.https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=qOdMBDOj4ec Even though the protagonists were very much on their best behaviour, this was an intriguing introduction and look back to the ‘culture wars’ which, I think underpin a good few discussions on Abcrit. It’s interesting you mention Celebrity Big Brother as I’d love to see how these two would be getting along after a couple of long days of demeaning BB house ‘tasks’ and a few too many cocktails of an evening….Or come to think about it, what about Scruton making an appearance on I’m A Celebrity Get Me Out Of Here. Perhaps he could give us all a lecture on how the British empire ‘civilised’ Australia…. Or maybe watching him gag on a kangaroo testicle would be equally enlightening.

LikeLiked by 1 person