The following is taken from a recent exchange of emails.

Tim Scott: Dear Robin, I thought you might like to read this by Clement Greenberg, re Abcrit discussions on “abstract content”:

“….The quality of a work of art inheres in its “content”, and vice versa. Quality is “content”, you know that a work of art has content because of its effect. The more direct denotation of effect is “quality”. Why bother to say that a Velasquez has “more content” than Salvador Rosa when you can say more simply and with direct reference to the experience you are talking about, that the Velasquez is “better” than the Salvador Rosa? You cannot say anything truly relevant about the content of either picture, but you can be specific, and relevant about the difference in their effect on you. “Effect” like “Quality” is “content”, and the closer reference to actual experience of the first two terms makes “content “virtually useless for criticism………indulge in that kind of talk about “content” myself. If I do not do so any longer is because it came to me, dismayingly, some years ago that I could always assert the opposite of whatever it was I did say about “content” and not get found out; that I could say almost anything I pleased about “content” and sound plausible……”

Robin Greenwood: Thanks Tim. We all define these things a bit differently, don’t we, but I’ve found the idea of “abstract content” quite useful recently. Time will tell if I’ve got it right or wrong.

Tim Scott: I’m interested. Are you saying that “abstract content” is different to any other sort of content? (Clem says it’s all the same but should be called “quality”; he doesn’t use the word “value”, as in value judgement.) Another point he doesn’t touch on is whether there is any difference between “sculpture content” and “painting content” in terms of definition.

Robin Greenwood: Yes, different, because no-one has done it before. But my idea of “abstract content” is a bit more prosaic than Greenberg’s idea on content. It’s something of a concoction, of course, but it’s about countering the idea that abstract art is all about simplicity and aesthetics. It’s almost a quantative thing, rather than a quality thing – and of course no guarantee of achieving painting or sculpture of value. Basically, I’m saying abstract art could put a lot more in from the beginning of actual, nitty-gritty activity – movement, physicality, spatiality, whatever, just general good-to-look-at stuff – complexity, in other words. As Alan rightly says, complexity is of no value in itself, but I’m saying it’s a better place to start than simplistic, “modernistic” ideas, tropes and formats.

For a while, the study of the body gave us something like complex content, but in the end it proved, I think, a limiting factor for abstract sculpture. Abstract sculpture should be amazingly unlimited in what it can do, particularly spatially. Hard to achieve, though!

In the end, the achievement of profound simplicity, such as you find in great art, is a complex matter. I don’t think you can fake that, you have to start from a complex position, putting in as much inventive abstract content as possible, see where it goes… What exactly “abstract content” is, well, that’s indefinable, of course, until it’s invented and specific, and the individual product of each artist.

Tim Scott: Yes Robin, re your last sentence, I have been asking that question for a long time! It’s not just being able to bugger about with forges and hammers either! I agree with virtually everything you have said; I find myself in exactly that position, struggling to put physicality, real three-dimensionality, movement, complex but meaningful relationships et al into my work.

It occurred to me that a useful parallel could be Music’s “content’ being ‘abstract’, whilst Literature’s being, well, literary – referential, i.e. NOT abstract.

Robin Greenwood: Yes, music is abstract, and it’s an analogy Tony Smart likes a lot. The thing is, music IS a language, albeit one that evolves. I’m not convinced sculpture is a language at all. If it is, it’s lost in translation! Or rather, it’s untranslatable.

Yes, we have to avoid the literary, and the literal and the figurative, but we don’t really know what exactly “abstract” means for sculpture. And over the last thirty years or so we have all talked a lot about physicality, and almost taken it for granted that that is central to sculpture. Mark Skilton, who has done some great work in the past few years, is really into physicality. Now I’m not so sure, because I’m not sure that it is really an abstract thing. Spatiality seems more abstract. Physicality seems a bit metaphorical, alluding to things happening in the material that relate to the body (?), against gravity etc. What do you think about this now? Personally, I want the thing to get more abstract.

Tim Scott: To take your last sentence first; I totally agree that we are aiming for greater abstraction as a means of making sculpture more original and more significant in the way it “works”.

I’m glad to know that Tony shares my enthusiasm for musical analogy. I have always found it a useful way of explaining sculptural intentions, though I am in agreement that, as always, explanations are fraught with dangers.

No, sculpture in my view also is not a language, but it is a unique mode of human expression with its own identity and essential characteristics, which are specific to it. Defining what these are is, of course, the major problem for all of us.

I have been fully aware of what the Brancaster sculptors have been doing, albeit only from photographs (the limitations of which I have been suffering for the last sixty years!), including what Mark has shown. If I have a criticism (general), it is not to do with spatiality or physicality (which I will come to), it is more to do with what I perceive as a continuing (retrograde) dependence on “manufactured” or what I have always called “given” form (which I know only too well is an immense problem with steel). How and with what methods this can be overcome, is an open question; but I am convinced that addressing it will further abstraction.

As regards your comments on spatiality and physicality as parts of essential abstract sculptural thinking, I am in total agreement that the former is vital.

The awareness of physicality became, for me, an essential part of my history in my attempts to escape the confines of “pictorialism”, and thus is probably of greater significance in my works as a liberating factor. I do agree, though, that if it is conceived as a characteristic that one tries to inject into sculptural form, there is a danger of being too associative, too attached to evocations of the natural world (though I wouldn’t have thought of it as anti-gravitational).

One of the most exciting aspects of ‘spatiality’ that I see as possible (in abstract sculpture of course), is to pinpoint the huge (physical) difference between “architectural” space and “sculptural” space as presently understood.

Robin Greenwood: Yes, I see the absolute liberating necessity in sculpture of asserting its physicality, as against the pictorialism of much of the sixties work. I wouldn’t for a moment argue against that, and “Sculpture from the Body” and your forging work etc. were absolutely necessary antidotes to that flatness and frontality. Be assured, I don’t want to do away with physicality in sculpture, it is after all very closely tied to three-dimensionality and spatiality, and in some ways those three things are inseparable. I just don’t want the “physicality” thing to be the focus of the content of my own work.

As to the point about manufactured or “given” form, I agree; and I think that is part of my thinking about increasing the complexity of the content. I’m involved in a large amount of gas cutting as a starting-point for my current work, in an attempt to get the steel and the space to be totally engaged – in other words, for the movement of the space and the movement of the steel to be unified, rather than the steel being thought of as the sculpture “proper”, which divides up the space, or merely occupies it. I’m no longer trying to put suggestions of physical attributes into the steel, only to open it right up to all sorts of very different ways of fully entwining with and engaging with and moving the space.

I’m also in agreement with you about the huge difference between architectural space and sculptural space – and that has taken me so long to work out. That’s very interesting coming from you, a trained architect. One very important aspect of this, as you pointed out once in a comment about Tony Smart’s work, is how the sculpture relates to the floor. So, combined with what I have said about not making the physicality allusive, the thing for me at the moment is how to make the SPACE of the sculpture exist naturally, from top to bottom. So, no feet, no legs, no props, just immediately into the spatial content of the work…

Tim Scott: Re the first paragraph, complete agreement; and of course we all as individual sculptors have to find our own routes (roots too!); in fact it would become boring and unproductive unless we all differed.

I sympathise (and empathise) with your steel problems; it is much the same with me; (I am chopping up plywood sheets into small parts to try to rearticulate them into meaningful configurations). As I have said before, the material has to obtain its own “nobility”, by which I mean that it ceases to be merely material, but becomes “live”. The “nature” of most materials is so strong that it becomes a battle.

I’ll have a stab at “spatial” definition for what it is worth.

Many have pointed to Architecture being akin to Music, i.e. its essence being “musical” in its construction, (abstract?).

I would surmise that “architectural space” is “distanced” space. It is perceived by the eye but can go beyond the eye, (towns, cities, the Acropolis!) If we hazard a small definition: of Architecture being “what the body DOES” and Sculpture being “what the body IS”, we arrive at the idea that Architecture operates by the occupation, (and displacement), of space, (according to human and structural need), whereas Sculpture operates by “extension”. The body does this in sport (high jump, long jump), dance, both anti-gravitational (Ballet) or gravitational (Bharata Natyam), or even simply reaching out, extending to a limit of the physically possible (Rodin)… I would suggest that this “limit” is exactly what differentiates “sculptural” space; The “possible” in architecture is different to the “possible” in sculpture, in that in sculpture it is contained, restrained, reined in by comparison, but of its own internal necessity, created by a non-functional structure embodying physicality, movement, the constraints of gravity, and of course “content”.

So, if we desire, as an ideal for an abstract sculpture, giving physical space and physical form equal weight and sculptural function, these two major constituents (albeit maybe not the only constituents), will in turn be constrained by the limitations of “concept”; of what they can do successfully, or not, as the case may be. (I learned a lot about this with “Cathedral”). Indeed, in my opinion, one of the debilitating factors in a great deal of modern sculpture, has been the total confusion over what constitutes sculptural form (and space), over that which constitutes the architectural since it has been assumed that they are synonymous or interchangeable, pace Constructivism, Minimalism, Caro et al.

I don’t know whether any of this rings any bells with you, but obviously it touches on areas that we are all concerned with in the battle to get an abstract sculpture flourishing from the roots that already exist… As (I think) you have said, it is quite possibly the case that abstract sculpture will occupy some sort of new territory that was not really conceived of previously; the question, of course, as always, how to go about it!

Robin Greenwood: Yes, I think abstract sculpture is going to occupy some brand new territory. Maybe it does already. And for that reason, I slightly disagree with your contrasting definitions of architectural and sculptural space, because I think that maybe the limitations you set for sculptural space are actually the natural limitations of figurative sculpture. I’ve always thought this is the main difference between abstract and figurative sculpture – that the latter is constrained by the limitations of the singular figure/body. All extension returns to the torso etc. Figurative sculpture is not and never has been really spatial. Physical, yes, but not really spatial.

With abstract sculpture, all bets are off as regards the spatial limitations. Who knows what they are? However, we agree that the early attempts (mine included) to make abstract sculpture more spatial than figurative sculpture ever had been were mired in the exact confusion you indicate, between what is architectural space and what is rightfully sculptural space. I think the big point to make here is that I don’t think abstract sculpture can be defined by the body any more than it can be defined by architecture. Abstract sculpture has to deal with sculptural space, without reference to anything else. And because figurative sculpture didn’t deal really with spatiality, it means abstract sculpture is in unexplored territory, entirely of its own invention – how exciting!

Tim Scott: Robin, I think you slightly misunderstand me; or maybe I haven’t explained myself clearly enough (in the past or now).

I do NOT intend for one moment anybody to think that my references to’ body’ characteristics in perception is to do with figuration, or any reference to appearances. On the contrary, what I hoped I had described was the fact that all our sensations, physical, optical, sensory, psychological, spatial, and so on, stem from our being ‘in’ human bodies; that is how our experiences happen. It is our biology, if you like, that conditions everything we need to create or enjoy the facts of what we call ‘sculpture’ or’ architecture’.

The point I was trying to put across was that the ‘biological’ conditions needed to create and perceive ‘architecture’ differ from those essential to sculpture; thus effecting, in practice, the resulting two separate art forms whatever the underlying purposes may or may not be.

I agree with you that a truly abstract sculpture can only operate in and incorporate ‘sculptural space’ (however we define that), and that is one of the great distinguishing factors setting it apart from past forms of sculpture, and that the pursuit of its inclusion into the very stuff of sculpture-making will produce something new and exciting.

To return to ‘spatial’ definition as ‘architectural space’, and ‘sculptural space’; their characteristics and differences; I would add a few more thoughts:

I would hazard a guess (only proven by practice of course) that if ‘sculptural’ space is extended beyond undefined real spatial limits, it automatically will become ‘architectural, thus destroying the very essence of what is being attempted spatially (i.e. something specific, particular, and unique to abstract sculpture). There is also the important matter of scale. The ‘fabric’ of the sculpture (whatever the materials may be) will diminish in visual proportion to the ‘distances’ travelled. Architects have encountered this for thousands of years, the oft quoted example of ‘entasis’ usually being cited. I would suggest that for abstract sculpture not to become’ architecture through its spatial occupation, it must never lose sight of its core (or it is in danger of becoming a sort of sculptural ‘forest’ ). This is a condition which I DON’T think applies to architectural space, and, therefore, is one of the key differentiating factors.

I would also say that the ‘foresting’ of sculptural space through unlimited extension, is in danger of sabotaging the essential physical factor of gravity and its key subliminal part of sculpture’s essence (whatever forms are invented to express it). I cannot think of a great sculpture that is not ‘subject to gravity”.(I suppose we could argue this one for hours).

There is also the factor of the reception, by the spectator, of whatever the sculpture is physically doing in ITS space. ‘Physicality’ (which we have all spent so much effort in injecting into a sculptural concept, and which is now more often referred to as three-dimensionality), will become the more unreadable the further it ceases to be the outcome of physical form, rather than of a supposed spatial generation. A spatial concept can only generate’ ‘sculptural’ ‘physicality, by collusion with form. The form can be minimal, but must condition the space within which and extending which it exists. I suppose the only sphere in which your quest for ‘abstract content’ could totally succeed would be ‘virtual’ reality (perish the thought !!!)

Another aspect of ‘architectural’ space that defines it as separate from the needs of a ‘sculptural’ one is the matter of ‘time’; of a peripatetic and displacing discovery and assimilation of what happens. This ‘exploration’ in time of an architectural world (allying it once more to music as many have pointed out) does not of course mean that you ‘discover’ sculpture at one go and then move on; and of course one can spend as much real time exploring a sculpture’s effect as a piece of architecture’s. But I would suggest that the concentration of this ‘effect’ spatially, and its intensity, especially its intensity, makes for a distinctive identity as abstract sculpture.

I am sure that there are plenty of other notable aspects to this subject that we haven’t yet unearthed as being noteworthy; but there again writing it is not doing it and making it happen!

Cheers, Tim

Robin Greenwood: Tim, Thanks for that… it’s a good analysis, yes. You are probably right. But I just have a sneaking feeling about the “gravity” thing, and the “core” thing, and even physicality itself – that they may be not so central to abstract sculpture. I repeat, maybe. Or perhaps we just have to come at them differently.

But to start, I want to relate the experience I had the last time I looked at a Degas sculpture in depth, about 6 months ago. That was at the Courtauld, “Dancer Looking at the Sole of her Right Foot”. http://www.artandarchitecture.org.uk/images/gallery/f6623fc5.html I think it’s a great little figurative sculpture, and you probably agree. It is, in parts, quite physical – in the twist and compression of the torso and the opposing crooked arm. But even here, I thing we are looking at something that has overcome gravity, because the content of the work is NOT about how the sculpture holds itself up against gravity, or reacts to the floor. It’s true content is not to be found in the standing leg, which is almost describable as being passive, or at least being pulled up, away from the ground, by the whole of the rest of the sculpture. It’s true, it has a core, and yes, it is physical; but it is already a rather strongly spatial thing, because the intent of the sculpture is to BE in space. In fact, after looking at it a good while, I was struck by a kind of unphysicality about it, in its seeming desire to get up and articulate itself in space…

I’m in trouble now because I can’t articulate this better. But Tucker said: “In Degas’ sculpture, the figure is articulated not as in Rodin from the ground upwards, but from the pelvis outward, in every direction, thrusting and probing with volumes and axes until a balance is achieved”. This gets near what I think, even though it’s an exaggeration for the Degas; but it is a kind of “proto-spatiality”; a more three-dimensional state, I think, than Rodin achieved. But it’s as far as you can go with the spatiality of the figure (though I always thought Kathy Gili’s first forged figure was VERY spatial, for a figure). Surely the way to go with abstract sculpture is more of this, no?

The troubles with the figure – for sculpture – is in fact “the core”, and perhaps too the symmetry. We have to keep returning to the torso. Can’t go anywhere else. Rodin even tried chopping it up to get over that one. Not sure that worked, really. Sculpture had to go abstract, to do something different.

The sculptural “forest” sounds bad, but I don’t know. Can’t rule it out. I think there are lots of things we haven’t tried yet. And I definitely want to – tentatively – explore a kind of anti-gravity. I know – dangerous. And I know that the worst excesses of figurative sculpture, like Bernini etc, have gone down the “unreal”, smoke-and-mirrors route. But I’m not interested in the Tony Caro “weightlessness” thing, of steel floating horizontally either. Nor am I interested in the Calder thing of floating suspension on a wire. What interests me most is exploring the idea of spatiality in any and all three-dimensional directions, and discovering spontaneously what the restraints on that are. That would be my abstract content.

Best, Robin

Tim Scott: Taking your last paragraph first, Robin:

I’m all for trying anything, and incidentally it is great that there is a group of sculptors willing to do just that (I hope !).

The trouble with ‘anti gravity’ is that it is totally dependent on material .Even the old stone sculptors could only do what it would allow them to; and of course the ‘liberation’ of steel has introduced its own quagmires of repetitiveness and mere acrobatics… Sculpture, by definition, must be a dialogue between material and intent.

I have always thought the Michael Fried ‘weightless’ idea misplaced; what he really meant, probably, was ‘deceptive’ or something similar. Calder has never impressed me very much since his ‘big idea’ is so literal and the results, though charming, hardly breaking any ice.

I hope very much to see your ‘spatiality ideas’ come to fruition (Don’t take too long !).

Some time ago, I saw the whole collection of Degas figures in a German museum on loan from America, and I share the sorts of feelings one of them generated in you. Likewise I think that Tucker’s oft quoted description is a little bit over the top, possibly because it could not remotely have been part of Degas own intentions; which Tucker might well have contrasted with his own observations and interpretations… Again, with Rodin, to my knowledge, his obsession with movement as a vital sculptural force does not really tally with a ‘grounded’ articulation; many of Rodin’s figures are articulated from various body points almost completely ignoring the ‘ground’.

It has always intrigued me to imagine what either Rodin or Degas, or even Matisse, would have made of our ‘abstract’ definitions, particularly if we abandon such terms as ‘physicality’ and introduce ‘spatiality’ as the key concept!

Be that as it may, I agree with you that sculpture HAD to go abstract, and that pushing the limits of abstraction is the task ahead.

Robin Greenwood: Thanks for that, Tim.

Finally a bit of sense on the matter. My only quibble — musical analogies don’t really work, and I say that as someone who once used to make free play with them. Music activates a different faculty of the brain. auditory space has no parallel with sculptural space, I’ve reluctantly had to learn. I’d still like to see you put up the colour photos of Tim’s Song for Chile in situ.

LikeLike

And as Hans Keller points out in his book, Criticism, music is not a language since it cannot be translated. It can of course be notated which is a very different matter. Leonard Bernstein, in his Harvard Lectures (available on YouTube) has made a valiant attempt to relate musical “syntax” to Noam Chomsky’s theories in structural linguistics, but I am afraid it ended in some absurdity. As far as I know no expert in musical analysis, Taruskin, Tovey, etc has made such an attempt.

LikeLike

By the way, there was a movement in “classical” music in the late 70’s and early 80’s, that of the self styled “new complexity”, a mutation out of Darmstadt, led by Brian Ferneyhough, Michael Finnissey and James Dillon, accompanied by manifestos and claims of radical innovation, in which every bar was subject to detailed subdivision, every rhythmic pulse broken down into further fragmented pulses; with absolutely no concession to “cognitive constraints” . the end result was indeed complex in the extreme, a challenge to both performers and listeners. Their work gets an occasional hearing on BBC Radio 3 even today. James Dillon’s Andromeda is a fine example (on YouTube) .

But the question which continues to be asked of such music is whether we ever want to submit to a second hearing. (Whereas the likes of Schoenberg, Berg, early Stockhausen repay such an effort) . Richard Taruskin says of it –“nobody took the “new” in New Complexity” seriously, not even its coiner.The movement was too much of a rear guard action to inspire much interest.

LikeLike

P.S. I have not been entirely fair about these composers. I actually quite like some of their stuff. Try Ferneyhough’s Liber Scintillarium 2012, admittedly a recent work, so they have progressed a bit. Take a look at the score for his String quartet No 6 , also on YouTube. Dillon’s Andromeda is also recent.

LikeLike

“You cannot say anything truly relevant about the content of either picture, but you can be specific, and relevant about the difference in their effect on you. “Effect” like “Quality” is “content”, and the closer reference to actual experience of the first two terms makes “content “virtually useless for criticism………indulge in that kind of talk about “content” myself.”

I like Greenberg’s way of putting this. “Quality” is a value-laden term and logically implies the act of aesthetic judgment and therefore the relevance of one’s “actual experience” of art in and through its instantiation in a particular work of art. Whereas “content” is a generic, categorical term that doesn’t so much imply the act of judgment as the framework of theory.

The “effect” of art on the viewer is conviction, conviction as to quality; because only a particular work has quality, the work’s ability to “compel conviction” (as Fried puts is) is necessarily one’s own conviction, which means that what convinces is one’s own specific experience and not any general theory. The modernist situation (as described by Greenberg) was forced upon artists (and their audience) by the fact that the very existence of art as such (meaning its possibility) was cast in doubt. It follows that art no longer exists as a given (whether institutional, historical, cultural, etc.); whereas before a thing that looked like a landscape painting was (i.e., counted as) a landscape painting, modernism meant that a thing’s existence as art (i.e., as a painting, a sculpture, a poem, a piece of music) can no longer be taken for granted. To put it another way, at a time when the concept of “art” had become so trivialized that “a stretched or tacked-up canvas already exists as a picture” (Greenberg, “After Abstract Expressionism”), only a work that compels conviction as to its quality could be said to amount to art at all in more than a trivial sense.

Greenberg continues with this: “The question now asked through [the work of Newman, Rothko and Still] is no longer what constitutes art, or the art of painting, as such, but what irreducibly constitutes good art as such.” Fried’s comment in footnote 6 of “Art and Objecthood” provides, in my view, the ultimate formulation of the meaning of modernism: “…what modernism has meant is that the two questions – What constitutes the art of painting? And what constitutes good painting? – are no longer separable; the first disappears, or increasingly tends to disappear, into the second.” “Post-modernism” has no reason to exist if not to challenge the truth revealed in Fried’s formulation – and that, as far as I’m concerned, means that post-modernism has no reason to exist at all, because its implication is that we have no reason to be interested in, much less committed to the experience of living at all, the value of our own lives.

Anyway, the term “content”, because it denotes a neutral, systematic concept – in opposition to “form” for example – fails to capture (for me) the specifically human dynamic at work in the experience of modernism, why it should matter to us (other than as a theory).

And the same goes for “abstract content.” As far as I can tell, the “abstract” exists in contradistinction not to the “figurative” but to the literal. Abstract art is art that by virtue of, and only by virtue of (because it has no exterior ground of support), its power to compel conviction as to its quality, affirms the continuing viability of art as such in an environment that is uniformly hostile to art and art-making, and indeed to any other activity that conveys value other than monetary value. A work of art that is not abstract in this sense is a mere object like any other in the world – and all the more so if it is placed in a gallery space or sold for millions of dollars at auction to a wealthy collector or tacked on the wall of a corporate office building.

I have no problem using the word “content” to refer to the heroic efforts of artists to continue affirm the existence of art today by making things that by virtue of their artistic quality don’t exist primarily or only as objects to be bought and sold, because these efforts affirm the possibility of value and gradations and judgments of value in a world where the false is nearly indistinguishable from the genuine article, and this happens by design.

LikeLike

All very well Carl, but just exactly and specificaly what is it that does “compel conviction as to quality” in new abstract sculpture. For me, at the coal face, so to speak, I can’t think of generalised things such as “quality” and “value” without coming to a sticky end pretty quick. Nobody can predict those qualities in advance, and to “intend” to achieve them would risk missing them altogether. We all might or might not be able to recognise them in retrospect, but you can’t make sculpture in retrospect, you have to take a punt and put it out. So “abstract content” is an effort to emphasise the idea that abstract artists need to think a little more specifically (maybe a LOT more) about what they are doing. AND, to think about NEW things, specific to abstract art (in other words, invent new stuff – abstract content – I keep coming back to it).

I was about to write that abstract content is not something that connoisseurs need to worry about. But then I thought, without content it’s all meaningless. What is it that one is going to have “conviction” about? And surely even the connoisseur, or anyone who wants to appreciate new abstract art, should get into that…? I suspect all else could be surplus to requirements.

Try the filmed discussion here: https://brancasterchronicles.wordpress.com/2016/06/20/brancaster-chronicle-no-34-robin-greenwood-sculptures/

LikeLike

Robin – I guess I’m one of very few participants here who isn’t a practicing artist, and I am therefore the last person on earth to advise you or other artists on how to do what you do. Everything I contribute here comes with that implicit disclaimer.

As someone who enjoys looking at art (abstract and otherwise), my responsibility (to myself) is to try to distinguish between what strikes me as “good” and the rest of it, and to articulate my basis for that distinction. If I can’t do that, I am left with the feeling that I can’t trust my own experience and feelings, that I don’t really know what I’m looking at. Enjoying art, if it’s different from enjoying ice cream, means being able to make distinctions of value.

Good art is art that convinces me, gives me faith, helps me to feel alive to my own senses and the world, lets me believe that there is such a thing as “value” in living. (Fried called this effect “presentness” as opposed to “theatricality.”) It’s the same sense of being convinced whether I’m looking at a cave painting or a painting by da Vinci, or Caravaggio or Soutine or Matisse or Morris Louis – the only difference being that the appreciation of modernist painting, because it is produced without the sponsorship of institutions like the church or the state, seems to require appreciation of the artist’s personal integrity to a greater extent than appreciation of art from pre-modernist traditions. That is: the quality of modernist painting seems to depend more nakedly or absolutely on the artist’s willingness to mean what he or she is saying than does pre-modernist painting. (Greenberg says somewhere that it’s the modernist artist’s “conception” that matters.)

The answer to the question, “’conviction’ in what?” cannot be anything in particular, other than the artist’s willingness and ability to use otherwise inert materials (pigment, canvas, pieces of steel) in ways and combinations that convey human significance, in ways that are meant, that suspend or defeat the inherent literalness of the materials so deployed to create things that are not mere objects but things that affect me in the same or similar ways that the art of the old masters (the quality of which is not in doubt) affect me.

But all of this is said by an outsider, to describe my own experience of looking at art. I assume it has little or nothing to do with the experience of you or Tim Scott in creating art. So if the idea of “abstract content” is useful in making good art, then by all means keep using it!

LikeLike

FROM TONY SMART

So, where in all of this are the new ideas and thinking about three dimensionality? The suitability afforded by the material that is steel in our case and by that I mean it’s immediacy and fluidity etc etc !!The “space” Robin is wanting to focus on will in itself have pitfalls. What about the spaces between steel work as well as inside the steel work {plenty on this subject in the Chronicles}Chatting to Hilde yesterday she brought up how the New sculpture cannot be taken in at one go.That in itself errs against anything being determined from the start.That calls for a very particular kind of structure which must keep renewing itself as it is discovered by moving around.It is in effect more like listening to a piece of music.This recipe approach to the ingredients and a stage by stage accumulation of the ingredients with invention does not seem to come together. Surely content, abstract,meaning arrives as it accumulates in the thing being invented and worked on. In the heat of many moments you would not necessarily know which was which, they could at any moment amount to the same thing.

I don’t think they can be separated out,only in the weird world of writing.

LikeLike

I can honestly say that if I was to think about what I was doing, and think about new things, abstract content or whatever, I would become totally paralysed and unable to work. Sounds to me a lot like conceptual art. I think it’s awrong place from which to begin.

LikeLike

And Carl’s comment should be taken on board, instead of just repeating the same old abstract content mantra.

LikeLike

It might be illuminating to compare „abstract content“ with concepts such as afterlife / reincarnation / complete extinction which defy any kind of rational analysis, but which can nevertheless have a great influence on how we live our lives.

Just as a belief in reincarnation might lead to different ways of coping with life as a belief in complete extinction, the search for abstract content is going to lead to a different way of making (and seeing) art as would a search for truth to nature, truth to materials, personal expression, ultimate reduction, hidden structures, perceptual awareness, etc. etc.

Robin is surely right about how arid much of abstract art has become. He may not agree with this, but to my mind “abstract content” is a kind of corrective myth, encouraging more interest, more variety, more ambition, less routine and less complacency in abstract art. And as myth, its function is to inspire and explain at an emotional and artistic rather than a rational and scientific level.

The search for abstract content (however vaguely expressed and subjectively interpreted) might then be one way to help “stave off objecthood” in abstract art at the present moment.

LikeLike

you’ld think that you were the only people trying for something “new”, and TALKING IT UP. There are different ways of being “new”. If one has been engaged with the full resources of the medium for a long time, innovation is more likely to occur naturally, without imposing heavy tortuous intent on it.

You may remember that in Steel Sculpture Part2 over on Abstractcritical, that I suggested a link between David Smith’s Australia and Tim Scott’s Song for Chile 2, and in a footnote said that Scott was a better sculptor than Smith. In Song for Chile2 Scott exploits the malleability and tensility of steel, the “steeliness” of steel, and is not afraid to use found elements, currently an unnecessary taboo amongst the Brancastrians, along with their predilection for chopping steel up into small staccato segments which sacrifice the very qualities just listed. (There are too many taboos in the current vocabulary of Brancaster in spite of all the claims to the contrary). There is an ease and breadth of conception of the way Song gets off the ground without fuss, and without “legs”.

What both Tim and Robin seem to be hinting at in this dialogue is introducing some kind of illusionism into their structures, such that small detail creates a change in scale in relation to larger elements, requiring a perceptual jump from one to the other, the sorts of thing Smith was able to achieve with great eloquence in his surrealist based early works incorporating parts that were either found, or mostly hand crafted by himself. But it would be hard to see this as anything other than a return to some kind of pictorialism?

But viewers will be compelled to ask of Robin, –“Why go to the lengths of crafting all these niggling little details, lacking the drawing eloquence of Smith (vis The Royal Bird 1948), in a spirit far removed from plastic and spatial integration and destroying the unique properties of the steel in the process, ( they could equally be made to destroy the properties of wood) , in order to contrive an opposition that could be achieved more directly and powerfully by other means. In no sense are they “in the material”. They are imposed on the material in some kind of stubborn and wrong headed pursuit of getting complexity at any cost into the work. (I have not yet seen the latest Brancaster Chronicle, so don’t know why was said).

But just to note that in spite of friendly advice not to do so, here we have the conflation of abcrit and Brancaster with parallel discussions of the same work, confirmation that they have become a vehicle of self-promotion.

LikeLike

FROM TONY SMART

Always interesting to hear what a bunch of inadequates we are from you but surely even from the great height that you look down on us from you would give us at least half a point for trying

Keep up the good work !

But more to the point why don’t you use this opportunity to have your say on Tim’s NEW work .

LikeLike

How your thinking has relapsed, Alan! I know you are never consistent, but not too long ago you were praising the progress of us sculptors and how far we had massively advanced things in terms of three-dimensionality etc. since Caro/Smith/Gonzales. Now you’ve reverted to “the drawing eloquence of Smith”, the “steeliness” of steel, found objects and all that old rubbish. How cast in concrete your linear heirarchies have become, and how they are dragging you down again and again! You’ve been looking at too many pictures of sculpture, I suspect.

And if you continue to cast aspersions upon work you haven’t troubled yourself to see, and muddy the water with your blanket dismissals, you’re going to get it in the neck again, and then you’ll go off in another huff for a few days. Let’s have a positive contribution from you. You started by saying “Finally a bit of sense on the matter”. What is? And yes, let’s hear your speculations from a distance on what Tim is doing now. Or is he in the shit-house too, and you daren’t say?

LikeLike

A quick word from the Great Height (New York City, center of the Art World, center of the universe) I look down at you all from.

First, this email exchange is great/wonderful/exciting/etc./etc. Very important for me. I’ve pulled out the old Tim Scott catalogs I have. I found a Xerox of a transcript of a talk Tim gave to architects and students at the North London Polytechnic Department of the Environment, October 23, 1980. Lee Tribe gave it to me 20, maybe 30, years ago.

About Robin’s “self-promotion”: maybe it’s important to keep in mind what a dismal failure Robin is at promoting himself and his fellow Brancasterites. The walls of Money, Fashion, egos, control freaks, whatever are unbelievably thick. Robin doesn’t really have a chance—even though he’s doing everything right as far as I can tell. But he has reached me. I’ve told my friend, my favorite Abstract Artist, Bruce Gagnier about Brancaster/Abstract Critical. Bruce is interested in/heartened by the work. I’ve told lots of other people too. Most just don’t have time for all the writing (I don’t have time for all the writing: I want to comment on/ask questions about every sentence in this post/thread/whatever it is)—but I got one young woman, a young woman from Scotland who somehow washed up on the shores of the New York Studio School, a graduate of the Edinburgh School of Art who’d never heard of Alan Gouk—I got her to watch Robin and Alan talk about Alan’s painting on a computer (or maybe she watched on a phone!). She was not uninterested. I feel my life has not been a complete waste!

And now about “abstract content”: Bruce Gagnier’s summer marathon at the Studio School (2 weeks of making 2 minute drawings from a model 8 hours a day Monday through Friday (to oversimplify just a bit)) just finished. At one point during the marathon a student asked Bruce, “What’s form? What does the word mean?” Bruce said something like, form is something that makes content compelling. It’s easier to understand in the context of older art: the content of ancient Egyptian art is eternity: form and content are more/less clearly/miraculously one thing in ancient Egyptian art. The student asked about the content of a Matisse, a Picasso. Bruce stumbled/groped around for a bit, then said I can tell you what the content of a Morandi is—or a Giacometti, or a de Kooning—but I can’t tell you what the content of a Picasso is. Picasso is too complicated. His content is one thing one day, something different the next. Maybe that’s what makes him a 20th century artist. Of course Bruce never really said what the content of a Morandi is. (He did say something about its being the whole history of Italy—but, as Tony Smart says, words are weird.) The important thing was that Morandi and Giacometti and de Kooning spent their lives searching for/trying to understand in a more/less simple/direct way what they were trying to “say.” For Robin the phrase “abstract content” seems to allow him to keep up his search—and to help him overcome the panic attacks he gets when confronted with contemporary figurative sculpture.

About complexity: some Studio Schoolers have made Robin an honorary member of the Abstract Expressionist Kitchen Sink school of art—a great honor! I look forward one day to having the time to listen to some of the music Alan is recommending. Morton Feldman was dean of the Studio School years ago. But it seems to me there’s something wrong with engaging with complexity so abstractly. It’s very sensible to talk about setting out to think about only two things for a year (mixing up space and steel, avoiding “configurations”) and just letting “complexity” happen. I think I understand Alan when he talks about becoming paralyzed if he tries to think about what he’s doing. But Poussin thought about what he was doing. He thought about the complexity of life and death—all that baloney.

And about photographs and videos—so inadequate—but what a joy when Hilde is directing the cameras!!!

LikeLike

Thank you Jock. I don’t think I have the time or the inclination either to explore Alan’s suggestions for indigestible-sounding new music. But I did see the ‘Hammerklavier’ sonata played by Murray Perahia last night in London – I believe he’s been and done it recently in NY too – and that’s my sort of complexity. (As an aside, the thing about Perahia is that you hear Beethoven, not Perahia). What a monumentally and stupendously great piece of music, and huge, great, rolling-on, unfolding, complex passages of sound appear entirely free and improvised as you are hearing them, as if they were spontaneously made up on the spot by a robot pianist of unbelievable genius. Shove your Modernist ‘ease’.

All due respect to Tim and his “Song for Chile”, but really we can’t keep doing that simplistic configurational stuff, and neither can he. Does Alan really want us to go back to some elegant “drawing in space” thing? I’d far rather fail miserably attempting something else. But I won’t.

LikeLike

P.S. You Americans can’t even spell ‘catalogue’! Huh.

LikeLike

At least you can more/less understand what I’m trying to say. It’s a much bigger challenge trying to spell through all your bloody English accents!!!

LikeLike

When I suggested putting up the images of Song for Chile in situ, Robin said “If I do I intend to heavily criticise it, even though I haven’t seen it.” So why plaster your “r unphotographable” sculptures all over the Internet if you don’t want people to draw some kind of conclusions based on them. In the present climate I don’t think a visit to your studio would do either of us any good.

It is the case that behind every act of criticism is the unspoken subtext — I know better and could do better. But I think you know me well enough to know that that has never been my attitude. It would be ridiculous of me. But that’s why Hans Keller called criticism one of the phoney professions. It admonishes the artist by posing questions that the critic himself is unable to solve himself. So it behoves all of us to try to be as un -egotistical as we can manage in addressing others work, and in presenting the case for our own work, if we have to! But Robin has been overstepping the mark in both directions with his tub-thumping about “new”. In any case “new” doesn’t necessarily mean good, or any good, as can be seen all around us today.

Would it not be better to take on board the comments of Carl Dantutch, (theoretical), rather similar to mine on content about a year ago, and my response to this new work, (practical) and only to this new work, and ask whether or not you may be barking up the wrong tree, instead of trying to shoot the messenger.?

On the question of details, these little islands of incident do tend to suggest a non-literal space , with pictorial implications, ( at least they do in Smith) –just a thought, something you might consider, with your touted ” open agenda”.But perhaps you know that already.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I read “Carl Dantutch” and thought, “God, another new name: how much time am I going to have to spend finding out about this guy?” Then it occurred to me that Alan has had some trouble with spelling in the past: he probably means “Carl Kandutsch.” Not that that’s a big help: reading Carl means at least thinking about Stanley Cavell, philosophy, etc. I ordered the Hans Keller book Alan mentioned the other day. Had never heard of Keller before. I think in Scotland there are dimensions to the word “serious” that are brand new to me. But there’s nothing “difficult”/intimidating about Alan’s comment about musical analogies: lots of fancy names, but what Alan says is “easy,” straightforward, deeply alive—a gift.

LikeLike

On musical analogies: —Sequential movement in music, whether it be mimetic, as in Debussy’s Poissons D’Or, or through harmonic and melodic development as in the Austro-German tradition (developing variation, Schoenberg on Brahms) , creates an auditory space, the moulding of psychological time (as opposed to metronomic or clock time), and simultaneously stimulates images in the aural imagination of the listener (which inevitably vary greatly from one listener to another. )

The last thing a sculptor would want is for his or her work to stimulate images in the mind of the observer, I think you’ll agree. Movement in sculpture occurs in the transition from one constellated node of action to another, (pace Rodin and Tim Scott), and the reciprocal pressure of the one on the other (as in painting), but one is constantly brought back to the concrete (unabstract) physical reality of spatial articulation . Tony Smart’s Stirrup, from the Stockwell Greenwich show could be taken as an example.

There has been a tendency in modernism for music to envy the reality of, and aspire to the condition of sculpture, rather than the other way round, (Varese, musique concrete, Zenakis, Ligeti ), by creating cloud clusters like the flight path of a flock of starlings in autumn for example — a concrete event in real space and time, or as with Birtwistle, to create a block of sound seen or experienced from different angles (at least that was the intent).

But sculptors would do best to purge musical analogy from their minds, certainly while working, constructing, don’t you think.

LikeLike

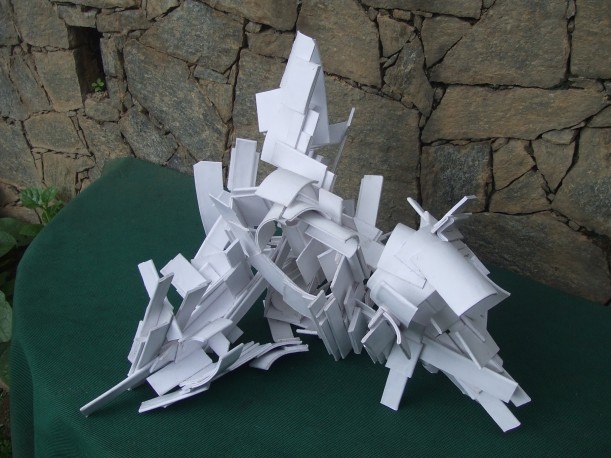

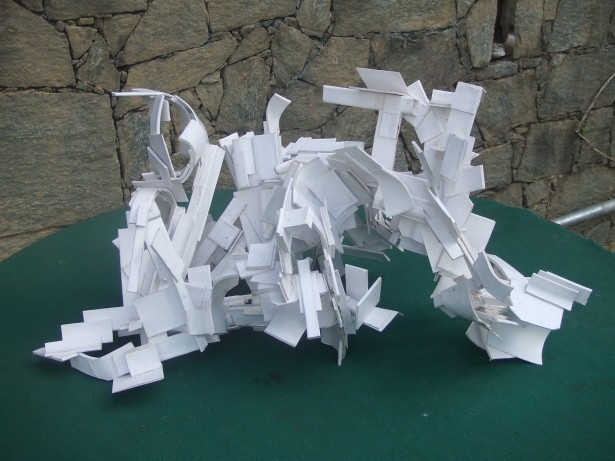

I really like the look of Tim’s work shown here – quite a head turning experience (albeit on screen). They have an exciting way of building sculptural form that is non-‘compositional’, not placement dependent but piece by piece accrued which develops into a structure that feels more abstract in its approach. The folding and physical cutting, bending and shaping of the pieces occupy and ‘hold’ their space / spaces in a really definite way. I like their treatment of mass which has a ‘haunting’ of the architectural about it (not a criticism). By this I mean the nature of the paper seems exploited as form rather than utilised for its immediate physical qualities – it could be torn, it could be really thick and it could be ‘paper’ thin. The flexibility of the material and its refreshing elegance (their whiteness is appealing) come to the fore though. The ‘for plywood’ in the title? Is that implying these are working sculptures and plywood will be used in future? I saw Tim’s last show of plywood sculptures at Poussin. These have moved on though, there are no more tiny pieces used as ‘editing devices’, the parts here seem much more particular and forthright. Confident art making is so rewarding to see.

LikeLike

A few visual ideas on the ‘steeliness’ of steel… and how metal has been used to open up the transparency of structures in profoundly visual ways:

http://www.archdaily.com/397949/ad-classic-the-crystal-palace-joseph-paxton

LikeLike

Loving the decorative cast ironwork.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Alan: “What both Tim and Robin seem to be hinting at in this dialogue is introducing some kind of illusionism into their structures”

“these little islands of incident do tend to suggest a non-literal space”

Well, I hope so, in both cases. But I think the big thing about illusion in abstract sculpture is that, rather than opening up new imaginary, illusionistic worlds of their own, they open up actual, real, literal space to the imagination. As I said in a catalogue essay for Tony Smart in 2009: “[These sculptures are] about… their own profound state of three-dimensionality. They explore sculptural space for us, because we can’t do it ourselves, we are literal and they are not.”

It is my purpose, in opening out the steel, to thus open out the space.

LikeLike

Tim Scott sent me the following:

Dear Robin, For what it is worth, from photos only of course:

I find that the ‘bunched/clustered’ masses of steel fragments definitely begin to break down the ‘givenness’ of the material. The way they are thrown out into space by the bars is, perhaps a little bit too much of a device, (but I qualify that by saying that since I am not experiencing them in real space; photos tend to graphisise everyrthing; I am not really reading their spatial effect adequately).

Given our ‘sculpture space’ discussions, I would say that these pieces definitely ‘grow’ from the inside “a core’ outwards (even if they were actually made doing the opposite; but that does not, in my view, take away from their spatial effect (what I can see of it).

I am struck (from the photo) by the way no. 4 comes to the ground, which seems to me to be more developed than in the others, which tend to rely on ‘point’ contact. I find the sculpture actually developing plastically with the way it comes to the ground.

There is, perhaps, a certain sameness in scale about the bunched cluster masses, which tends to give ‘balancing’ characteristic to the piece as a whole. I am not sure what I would do; perhaps select dramatically different thicknesses of source material perhaps ?

Regarding steel as the basis for conception, I would be the first to admit that the ability to join it through fusion ‘welding’ , is of the essence. One of the dangers of this (for anyone) is to rely so much on the spatial acrobatics that are possible as a consequence, that ACTUAL weights and densities and masses; their relationships to each other (under gravity), their function (aesthetically), are ignored or at the very least overlooked. (It is when one is obliged to work in something other than steel, that the full realisation of this hits !).

Cheers, Tim

LikeLike

“No 4” refers to “Photicon Nakamichi”

LikeLike

Interesting that Tim’s comment on the welding trap are very similar to some of the things I noticed when I actually saw the works in the flesh, and so too the suggestion of using thicker steel plate, and fashioning it into segments that are themselves three dimensional, instead of the hanging Christmas decoration effect of the thin plate fret worked into curlicues that pertains at the moment in much of the detail.

The gains that were made for sculpture in steel following Tim’s pioneering of the expressive qualities of the malleability and ductility of steel in his smaller sculptures, the Mudras and Lavitallanas? (spelling?- I don’t have my Scott catalogues with me) were followed by the From the Body episode, with its concern with the effects of gravity on structure, with forging playing a large part. As a result of this period and as the figurative or representational engagements waned, there were more gains for plasticity — Smart’s Torrent and Vulcan, 1988 , and Gili’s Bold and Llobregat 1989-90 , and by Scott himself with his small sculptures made in Germany in the late 80s and early 90s — Feminine for Structure, song for Rhythm? Etc. , and into the 90s particularly by Gili’s small scale works — Vervent 1, 2, and 3, Volante 1998, and Flow Free 2005 and Episodes 2010.

Scott’s Song for Chile 2 1992 is the best large scale sculpture produced by anyone in recent decades, showing what can happen when the stimulus of new surroundings and access to an unexpected treasure trove of unusual steel is offered to an artist who has been working with steel, and its unique qualities over a long period of time –plus no doubt technical helpers to realise a work on that scale. What is good about it?

The “drawing ” in it is not linear so much as wave-like, expanding from the ground without “legs” , opening out three dimensionally to form a continuous structure which has no obvious “architectural” schema. Both Sam and I have had difficulty accepting that the two views of it afforded are of the same work. How many Songs for Chile are there ?, I asked Tim. The word “configuration” is quite inadequate and unsuitable to characterise the movement in this sculpture. It is effectively meaningless and should be dropped from the lexicon.

But concomitant with the gains In the expressive qualities, the steelness of steel, yes there is such a thing, and it’s malleability in the service of plasticity, there was the issue of its spatial organisation, which has brought to the fore other questions — 1. The interaction at a distance, the extent to which , or whether or not, literal three dimensionality is overcome as sculptural parts interact across space. Do they interact, or are they simply placed in contiguity as are any quotidian objects? (This echoes the object hood dilemma in painting).

And 2–Does the structural logic, or the anti-structural dis logic of the entire set-up have credibility as a whole? Even a work which deliberately sets out to defy structural norms, ” the logic of ordinary ponder able things”? has in the end to deal with gravity and the dialogue between disguised engineering structure and the sculptured order, — heavy weights of quantities of steel cantilevered from a single weld for instance, even if appearing to be unsupported from some angles of view, need to be supported somehow, but in a way which coheres throughout the work and convinces that it has really been considered and answered.

Just as in painting, planarity cannot be escaped by diffuse handling, so in sculpture structural credibility cannot be disguised by fudging key junctions or by obscuring them with islands of decoration, ( a thought that occurred in front of some of Robins new work).

” Abstract” sculpture cannot exist in a structural i.e. Gravitational vacuum. It cannot just hang in the air, ( a return to “weightlessness”). Abstract cannot be achieved at the expense of physicality. This is how the dilemma of getting above four foot six in height came to assume importance, or to be a problem, and it has yet to be answered convincingly. These are just some of the issues raised by Robin’s new work, and he is to be congratulated for having raised if not always solving them, if that doesn’t sound pompous. Remember he and I have discussed all this in a friendly spirit in front of the work. Incidentally, the photos give little or no idea of how they are in real space and time. They are much bigger and more assertive spatially than they look.

LikeLike

Sorry Carl, I seem to have a touch of dyslexia over the spelling of your name. I’ll try to get it right the next time. And thank you for pricking the Sweet bubble so effectively!

LikeLike

I remain convinced, despite Alan’s “friendly spirit”, that’s he’s wrong on this one, because his notion of physicality is so strongly tainted by figuration, and almost all the work he mentions here is figurative to a degree. I think we are beginning to see the back of that, but Alan hasn’t caught up yet. We shall see if a new, more abstract physicality develops, which in the case of my work, I hope will have more emphasis on spatiality and three-dimensionality, neither of which the work he cites really addresses – in my opinion.

I also think it is just irresponsible to pronounce “Song for Chile” “the best large scale sculpture produced by anyone in recent decades” when nobody outside Chile, including Alan, has seen it, other than in rather poor photos. Yet more stuff from on high, Alan.

LikeLike

There is a good comment from Alex Harley on Brancaster: https://brancasterchronicles.wordpress.com/2016/06/20/brancaster-chronicle-no-34-robin-greenwood-sculptures/comment-page-1/#comment-329

LikeLike

So you are not going to put the photos up of Song and other sculptures I mentioned, and let people judge for themselves as far as is possible in photos. ?. And the idea that they are figurative is stretching credibility. Let’s see them.

LikeLike

Volante figurative? And the Vervents and Episodes? Come off it.

LikeLike

FROM TONY SMART

On “Bridge of Echoes 1”

This piece could have been interpreted by me as the least articulate and interesting in its extremities but for the following reasons, and after much peering into the photo I like it the most

.

I see pressure, not the pressure of elongation but of piece on piece of paper moving in so many different ways against one another and in such large numbers and coming from all directions with a multitude of attitudes.This squashes the space which was there out and in the squashing and squeezing and the alternations piece on piece building to larger direction changes and movements through the piece the space becomes a memory. It is not contained or described space but a physical memory as the pressure is piled on. There would appear to be a purpose to the shape of the whole .Not something opening to the world as physical material but of the space leaving the sculpture. This is not a gentlemanly dialogue between space and material looking for unity but the one moving the other to the margins only to be squeezed back in. So, there is no ambiguity on the margins between the space of the sculpture and the space around the sculpture as I perceive it.

Put another way its like squeezing wet clay in your hands and out from your fingers but alas clay being inert you have to bring it back again. The sculpture on the other hand appears to be able to not only keep this going but the sculpture which is being continually rebuilt is rebuilt in an entirely new way.

LikeLike

I have just put up two more shots of “Bridge of Echoes I” at the end of the article, but I don’t seem to have a view of the other side of it.

Alan, if you want to put up some photos, put them on your facebook page, then you can link to it.

LikeLike

These “comments”/this discussion is SO great!!!

We spent some time squeezing clay during Bruce Gagnier’s sculpture marathon at the Studio School a week or two ago. Thanks to Tony’s marvelous take on “Bridge of Echoes I”—“space leaving the sculpture”!!!—that marathon business means a lot more now. And, of course, Tony’s “space becoming a memory” thought is very deep/rich.

I haven’t seen any of this sculpture. I don’t even understand all the writing. But I understand more and more of it—and “see” more of the sculpture—as new comments come out. Alan and Robin disagreeing about what’s figurative and what’s not helps me not only with the From the Body “ancient history,” but with Robin’s new work.

That “Song for Chile 2” sculpture looks pretty good to me. I’ve only seen the 2 photos “everybody” knows. Of course, I’d like to see the real thing—but, as all Studio Schoolers know, sculpture comes in two parts: the tangible part and the intangible part—and the intangible part is the most important: the “song” in “Song for Chile 2” is more important than the steel. It’s true they can’t be separated, but they can kind of get separated in writing. It seems to me there’s a lot of “singing” in Tim’s work. I’m afraid the “singing” kind of embarrasses a lot of cool New Yorkers. I love it!

“Lavitallanas” is correctly spelled “Lalitasanas” (I think: there are pictures of “Lalitasana III” and “Lalitasana IV” (both 1981) in a nice 1989 Tim Scott catalog: the catalog also includes an essay by Alan Gouk (in German AND in English).

Many thanks for the new photos of “Bridge of Echoes I”!

LikeLike

I too like Tony’s account of Bridge of Echoes. Sweetness and light seem to be breaking out all round. And once again thank you Jock. You have become a scrupulous aficionado.

LikeLike

P.S. I can’t transfer the Song for Chile colour installation shots from email to Facebook, or anywhere else it seems. But I should not have tried to describe it or characterise it as a wave or anything else. It is nothing like a wave. I just want to indicate that it cannot be described as a “configuration” either. Nor is it linear or a kind of drawing. It, like these new paper for plywood sculptures , is a summation of all the earlier works in steel, including the earliest Adele sculptures, which also cannot be characterised as an arch configuration, even though Tim’s account of Rodin’s Adele as a kind of arch lies behind them. They are much more plastically complex and 3D than that. Tim’s description of the Rodin Adele needs to be re-read to see how much more sculpturally is at stake in them.

LikeLike

LikeLike

LikeLike

LikeLike

I just worked out how to do this. I did say they were not good photos, and I do hope Tim doesn’t mind, but I can’t get hold of him.

And I do rather think, Alan, that your thinking is wishfull…

LikeLike

Meanwhile, here’s a Christmas tree decoration. “Wexin Yang” reworked a little…

LikeLike

I think this is better–not sure what that means though. It IS fun to peer into the photos. And for sure: you guys just don’t understand complacency!

LikeLike

‘Better’ is of the essence… Pop by and have a look at the real thing. Come by way of Chile.

LikeLike

Yesterday Sam Cornish showed me some pics of big steel Tim Scotts in Canada he’d recently seen, and on a quick viewing they looked a lot more interesting to me than “Song for Chile”. Maybe we can get Sam to post a few…?

LikeLike

Good to hear Mr. Cornish is alive and well–and roaming around in Canada (my old hunting grounds). I miss the Modern Sculpture tweets!

LikeLike

Thanks a lot. Look forward to any new pictures.

LikeLike

So this is your sole evidence for “the best large scale sculpture produced by anyone in recent decades” – these 4 photos? No disrespect to Tim, but that is a fantastic claim.

For anyone who is interested: (I’m sure there are other ways, but) to get a pic in the comments, Tweet it first, then right click on image, copy image location into comment and it comes up as a picture. Get tweeting, Alan!

LikeLike

This is from Tim Scott:

Having only just read (hospital and computer problems between them) the abcrit comments on Robin’s and my ‘duologue); I list below some reactions to a few of them:

Alan:

I don’t pretend to have your musical expertise (though I did spend my youth listening to Hans Keller), but I do find musical wording a sane form for commenting on sculpture sometimes (maybe not painting). I certainly do nor want to imply that I find any ‘parallel’ between ‘musical space’ and ‘sculptural space’. The only ‘parallel’ I can think of is an emotional one.

I’ll look out for Darmstadt on R3, but I don’t think I would really want to listen to music that I wouldn’t want to hear again !!

Karl Kandutsch:

On the contrary, a lot of what you say is absolutely about WHY one would want to be an artist, not about HOW.

Alan:

“….if one has been engaged with the full resources of the medium.for a long time, innovation is more likely to occur naturally…” YES

Emyr Williams:

The ‘paper’ works were simply not having anything else to work with at the time. I have been, and am, working with plywood in a similar vein, (a long way from the Poussin pieces).

Tony Smart:

I love your phrase: “…this is not a gentlemanly dialogue between space and material looking for unity, but the one shoving the other….’ it is wonderful when someone really ‘gets’ it.

Jock Ireland:

I am very pleased that you think that there is “a lot of singing in my work”; I couldn’t want for better.

Jock Ireland (again):

Yes; please DO peer into the photos (with a magnifying glass!); I hope that will reveal more.

Tim Scott.

LikeLike

The silence is deafening. I was expecting Alan to make more of a case for “Song for Chile” now that we have up the photographs that he has pestered for since early May. Obviously no one else can form a definitive view of the quality of this work from these pics, other than Alan. He no doubt feels the case is made, since he is the one who has made it; and without the certainty of genius he attributes to “Song for Chile”, his theory of Modernist sculpture falters somewhat.

Personally, I doubt very much what he has said about it so far. From what I can see, the “drawing” IS linear (because we “follow” it), and perhaps repetitively so. It DOES have an obvious “architectural” schema; though it may well be a confused one, from different views – or it could be that the “end” views just don’t have much to say about the side view. The word “configuration” IS adequate to characterise the movement in this sculpture; it’s an up-and-down arch with a side extension to support it. It has precedents in Rodin’s “Adele” and Tim’s own “Adele” series (of which I suspect it is not the best) and affinities with the St. Martin’s “lion” project. It is undoubtedly semi-figurative.

I think Alan’s desire for this work to be “great”, in the (figurative) Gonzales/Smith tradition that he so reveres, blinds him to its shortcomings. His theory won’t allow it to fail, because otherwise that tradition will have ground to a halt prematurely and completely (apart from Gili?); nor will it allow new work to show up its shortcomings (for example, Mark Skilton’s “Greedy Granadilla” is a far better “large” steel sculpture, if that’s what you are looking for). I have all due regard for Tim and his work, but I feel Alan is imposing upon him and this sculpture something which is at worst untrue, and at best, outdated.

The “following” (by the eye) of a linear motif in sculpture (tensile or not, “wave-like” or not, or indeed the “compositional” aspect of so much so-called “abstract” sculpture to date) is one of the things that we have tried and at least partially succeeded in overcoming or breaking down in recent years. There is further to go on this (perhaps a lot further), but the chopping-up, diversifying, and reconstituting of the material into new and inventive visual/physical structures – which is evident, ironically, in Tim’s new work (or is that just “paperiness”?), and which Alan hates so much – is a part of that process.

Like everything that is tried, it carries a danger, and the “Christmas decoration” jibe that Alan has made against my work is of course just about the worst thing anyone could say about a sculpture; but I welcome it, as I welcome any criticism, because the tiny seed of truth that I recognise in this barb arms me to be vigilant against just that thing. I’m confident Alan misses a much bigger truth, but that’s for others to say.

LikeLike

Robin’s kind of awkward tone here IS kind of awkward. He opens himself to a sound thrashing on many counts, but I think it’s an important/useful comment.

(I haven’t seen Tim’s Song for Chile. I haven’t seen most of the work talked about at Abcrit and Brancaster. Still, I’m an avid Abcrit/Brancaster “visitor.”)

What’s great about Robin’s comment is that it makes clear or at least helps me understand a bunch of things about the “steel sculpture” he and Mark and Tony are making—and the sculpture Robin describes as being part of the “(figurative) Gonzales/Smith” tradition. Robin has many interesting/generous things to say about the differences between these two points of view/“traditions.” (Needless to say, it’s wrong to lump Robin’s and Mark’s and Tony’s sculpture into one “point of view.”) What’s striking to me, what I want to question at the moment is Robin’s embrace of the idea progress in sculpture.

Robin suggests that Tim’s “Song for Chile” might be “outdated.” Robin says he and Mark and Tony and even Tim have moved past “the “following” (by the eye) of a linear motif in sculpture.” Robin is interesting and exciting when he talks about “the chopping-up, diversifying, and reconstituting of the material into new and inventive visual/physical structures.” But the idea that just because what even Tim happens to be doing today—no matter how strenuously considered it might be—is different from what Tim was doing when he made “The Song for Chile”—that that makes it better seems to me very questionable.

I just want to question this “embrace” of the idea of progress. I’m not trying to dismiss it. I just want to think about it in the context of a few different “things.”

First, Queen Victoria. She believed in progress, didn’t she? I think she believed in those fancy railway stations pictures of which Robin put up here the other day. But isn’t Queen Victoria a bit out of date?

Second, Yves Bonnefoy. He died the other day. I’ve been reading one of his essays about Raymond Mason. Here are the first two paragraphs of Bonnefoy’s essay translated/butchered by me. The paragraphs are not really about progress—and I’m not trying to lump Robin in with the typical sign-makers of today—I’m just asking “questions.”

“The art of our time often is nothing more than the production of signs, signs that have no function other than announcing that the guy who came up with the signs is “different.” Just like signs in Ferdinand de Saussure’s system of thought, the creator exists only as somebody different from other creators in a purely formal system of relations that’s open up front, at the end we call the future. It’s easy to understand why. Science has shown us we’re riven by forces disconnected one from the other, forces essentially unknowable. Belief hardly ever delivers the experience of a God who guarantees the unity of our relationship to ourselves. Under these circumstances, our languages can seem to be nothing more than hypotheses for knowledge or action, forever incomplete, at every instant fallacious—but our languages might just as well be dinghies thrown into the abyss, the only reality we might claim. Now works of art, works of poetry, have always been—albeit in a way for a long time controlled by the idea that there’s just one world—sort of particular idioms, personal idioms, added to the speech of the group to explore details, sometimes urgently, sometimes dreamily. It is then natural enough that in our time, a time that recognizes only the idea, a distressing idea to be sure, of the arbitrariness of signs, we pay special attention in our artistic research to the exigencies of signs. We take pleasure watching a new sign emerge, watching it develop, and when the time comes watching it give place to even newer signs.

“But this kind of fun is not without risks: when these new beginnings and the fights that go along with them, far from engaging with the real world outside of us—it exists: life and death are proof—reject it, reject the real world completely. What’s endorsed, what gets stroked is the looseness, the irresponsibility of signs, their capacity to create worlds out of nothing, to take over the spirit: what takes the stage is abstraction: it responds so well to the fear of existence, to the denial of finitude that one encounters so often among artists. What is suggested is that the world is nothing but the product of signs. Does not daily existence include great realities as simple as they are universal, realities you can’t turn away from even today, especially today, without being hopelessly naive or simply immoral?”

Third, this exchange between Rosalind Krauss and Jed Perl in the current New York Review of Books. Again I’m not trying to suggest Robin thinks the way Yve-Alain Bois does. I’m just suggesting this kind of thinking is in the air.

In response to:

Which Matisse Do You Choose? from the May 12, 2016 issue

To the Editors:

Jed Perl cloaks his dismissal of the art historical and critical work of Yve-Alain Bois with a caution about the straitjacket of systematicdiscourse, which he believes must close off the work in question to the “accidents, coincidences, escapades…even outright mistakes” in the practice of a given artist [“Which Matisse Do You Choose?,” NYR, May 12]. He goes on to demonstrate the reliance onsystem in Bois’s work on Matisse, Kelly, and the contemporary art informed by the writer Georges Bataille (“Formless”). In his masterly essay on aesthetics, “Music Discomposed,” Stanley Cavell speaks of great criticism as insisting on asking “why the thing is as it is, and characteristically…put[ting] this question, for example, in the form ‘Why does Shakespeare follow the murder of Duncan with a scene which begins with the sound of knocking?’ [a question Mallarmé devoted an essay to]… The best critic is the one who knows best where to ask this question, and how to get an answer” (Must We Mean What We Say?, p. 182).

Surely getting an answer and even being moved to ask the question requires an intuition of the system out of which such an effect is precipitated. If in his “Matisse and ‘Arche-drawing’” Bois is impelled to ask why Matisse could control line (particularly in his drawings of the 1930s) in such a way that the flat page between those contours seems to distend itself toward the viewer with an uncanny effulgence, he is asking why drawing can produce the luminosity of color. Of course, the writer who has never had this visual experience will overlook the imperiousness of this question and accuse the one who poses it as simply relying on system. Jed Perl is such a writer, and his insouciant disregard for the many instances of Bois’s posing of the question why—for examplewhy Ellsworth Kelly revolted “against…a European tradition of utopian or idealist compositional strategies”—betrays his own difficulty in making the relevant distinction between one artist’s strategy and another’s.

In the interests of full disclosure, I am the colleague with whom Bois has collaborated, in our exhibition “L’Informe: Mode d’Emploi”; in our journal October; and in the textbook Art Since 1900 (Thames and Hudson). I only hope my own work finds the right places to ask and find the answers to why? as effectively as does Yve-Alain Bois.

Rosalind Krauss

University Professor

Columbia University

New York City

Jed Perl replies:

Consider the key words in Rosalind Krauss’s letter: “system,” “strategy,” “practice.” This is the terminology of a person who prides herself on being a rationalist, on preferring what she conceives of as sense to what she dismisses as sensibility. But when it comes to the arts, the people who fetishize sense all too often end up talking nonsense. (Which is not, of course, to say anything against sense.)