“Maricopa Highway”, 2014, oil on canvas, 106.6×106.6×3.1cm, ©Mary Heilmann; Photo credit: Marie Catalano, Courtesy of the artist, 303 Gallery, New York, and Hauser & Wirth

Mary Heilmann, ‘Looking at Pictures’ is at the Whitechapel Gallery 8 June – 21 August 2016

http://www.whitechapelgallery.org/exhibitions/mary-heilmann-looking-at-pictures/

Among the paintings that conclude Mary Heilmann’s ‘Looking at Pictures’ at Whitechapel Gallery is ‘Maricopa Highway’ (2014). One of Heilmann’s most recent works, it is evocative of driving at night along scenic highways and the familiar narratives of road movies and video games. ‘Maricopa Highway’s’ nocturnal palette is uncharacteristically naturalistic and subdued, Heilmann’s vibrant choice of colour having been quickly established in her shift from ceramics and sculpture to painting in the early 1970s. In many ways this, like the other paintings of roads and oceans in the final section of the exhibition, feels like Heilmann making a definitive move into more overtly representational painting; diagonal stripes suggest perspective recession and more literally, road markings illuminated by a car’s headlights. The real Maricopa Highway is a little-travelled state highway in Southern California and the route taken by Heilmann’s parents as they drove from San Francisco to LA during her childhood. This describes well the way in which Heilmann makes paintings in which a personal narrative is alluded to through her choice of title, for example, ‘311 Castro Street’ (2001), which was her grandmother’s address, ‘Our Lady of the Flowers’ (1989), the title of a book by Jean Genet, of whom Heilmann says she is a fan. This personal connection to her own work is consistent through titles that denote significant memories, friendships, places and songs. Heilmann herself assumes a self-referential position in her 1999 memoir The All Night Movie, in which she wrote, ‘Each of my paintings can be seen as an autobiographical marker’. ‘Looking at Pictures’ makes much of Heilmann as an artist who paints her own life – the exhibition title itself is taken from a section of her aforementioned biography – but there is nothing pure or definitive about Heilmann’s approach to painting. Where she embraces abstraction as a referent for personal experience, she also denotes its more formal concerns, albeit with a casual and knowing imperfection. In ‘Maricopa Highway’ the duality of Heilmann’s methodology is well illustrated. She presents not just a scene of driving at night towards a distant vanishing point but a fractured reality of two different viewing positions placed consecutively. The diagonal lines are both road markings and a reduced abstract form composed on a shaped geometric canvas. Her application of paint is in part dense and almost flat, in part a translucent gestural wash. Throughout ‘Looking at Pictures’ Heilmann’s paintings reveal an adjacency of formalism and narrative, simultaneously telling stories of the proximity of herself to the work and also her objective distance while working towards an established language of abstract motifs.

“Primalon Ballroom”, 2002, oil on canvas on wood,127×101.6cm, ©Mary Heilmann; Photo credit: Oren Slor, Courtesy of the artist, 303 Gallery, New York, and Hauser & Wirth

Born in 1940 in California, Heilmann studied poetry, ceramics and sculpture before moving to New York in 1968. Here she took up painting at a time when it was hugely unpopular, if not considered to have died altogether (again). ‘Looking at Pictures’ begins at this point, with a selection of her works based on the square, the grid and architectural details, such as ‘The First Vent’ (1972) and ‘Little 9×9’ (1973). Both paintings depict irregular grids, made by Heilmann manipulating the painted red surface with her fingers to reveal the dark ground beneath. Heilmann’s gridlines wave fluidly across the canvas – her lines are loose and hastily rendered on a surface that reveals the paintings’ making through their disrupted top layer of smeared pigment. Heilmann cites the modest vocabulary and flawed perfection of Agnes Martin’s canvases as an influence at this point, but both artists exhibit a widely divergent treatment of the grid. For Martin the grid was a substitute for the most fundamental form of drawing, a rational system of lines that formed organisational structures on a canvas. They are quiet and meditative, produced methodically and with great control. The flaws in Martin’s lines are temporal, identifiable only after looking closely at her paintings. Heilmann’s grids have none of this subtlety. They are spontaneous and vibrant. The imperfections in the regularity of the grid’s rendering are at the forefront of the experience of looking, the artist’s hand is assertive and her colour palette highly saturated. What ‘Looking at Pictures’ does well is to avoid any sense that Heilmann is on a direct journey towards creative genius. Instead, the initial part of the exhibition demonstrates an honest clumsiness in her early attempts to scrape, handle and drag paint into the loose geometry that later became a personal language. Heilmann’s early paintings present themselves literally as their own experimentation. ‘The First Vent’ (1972) feels like a significant work in this regard, signifying Heilmann’s subsequent use of formal elements to explore pictorial space but that also reference real-world experiences. ‘The First Vent’ is on the one hand a self-reflexive grid painting, and on the other, a literal depiction of an air vent. Her early geometric works follow a pattern of painted forms such as rectangles, squares and grids that could be identified in the interior architecture of doors, grills and latticed windows, often produced at life size. Unlike the distant objectivity of Martin’s geometry, Heilmann’s intimations of the everyday domestic world are embodied experiences, unkempt in execution and shamelessly fixed in narrative.

“Matisse”, 1989, oil on canvas,137.1×137.1cm, ©Mary Heilmann; Photo credit: Michael Klein, Courtesy of the artist, 303 Gallery, New York, and Hauser & Wirth

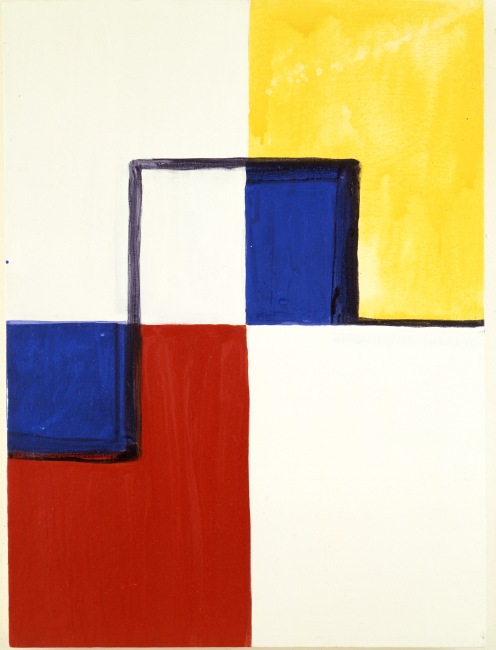

Heilmann’s subjective relationship with Modernist abstraction placed her in opposition to the fundamental American position on painting in the early 1970s. In her own words she ‘didn’t fit in with the group informed by the [critic Clement] Greenberg-influenced discourse.’ Her casual approach to formal investigation allowed her to make paintings that felt new, and they had an irreverent edge. When Heilmann’s work cites Mondrian, Matisse and Albers it does so with a lack of formal etiquette. The two red canvases of ‘Chinatown’ (1976), in which one is painted over a blue ground, the other yellow, appear to reference Albers’ ideas about simultaneous contrast. If they do so, however, we are convinced that any element of formal investigation is nominal, as Heilmann’s choice of colour is also associated with the decoration of the Chinese restaurants in the area where she lived in New York in the early 1970s. ‘Little Mondrian’ (1985) is one of Heilmann’s more direct allusions to Modernist painting. She adopts Mondrian’s signature palette of red, yellow, blue and white and treats it with an informal wit; sloppy brush marks are left visible in translucent, relaxed rectangles, contoured rapidly in watery black lines. There is an evident interest in reinventing the standards of Modernist abstraction by identifying its essence and blurring it round the edges. Formal explorations are messed up with drips and blots of paint, surfaces are never flat or visually still. Her almost ‘monochromes’ such as ‘The Big Black Mirror’ (1975) and ‘Green Weave’ (2013) have hurriedly applied or scraped back layers of colour – they have not one painted surface but several. In ‘Green Weave’ Heilmann ignores the Modernist palette entirely and chooses instead the colour of the natural world, and not the abstract one, in which to make a dishevelled green square.

“The Thief of Baghdad”, 1983, oil on canvas, 152.4×106.68cm, ©Mary Heilmann; Photo credit: Pat Hearn Gallery, Courtesy of the artist, 303 Gallery, New York, and Hauser & Wirth

Heilmann’s formative period spent working in ceramics and sculpture has had a prolonged influence on her. ‘Looking at Pictures’ includes a selection of Heilmann’s ceramics and they have a clear connection to her paintings. She is influenced by the jewel-like colours of ceramic glazes, which is made explicit in the cobalt blue abstraction ‘Ming’ (1986). She uses techniques of dripping, layering and pouring to apply paint, which derives from her earlier work with glazes. Heilmann considers the whole painting – its sides, top and edges – and paint is applied to each through rapid brush marks, dribbles and drags, either intentionally or incidentally. In her early paintings such as ‘Little 9 x 9’ acrylic paint is sculpted like malleable clay with Heilmann’s fingers to create structure and define space, generating form through a traditionally sculptural process of adding or subtracting material. In ‘Gordy’s Square’ (1976) (Gordy being Heilmann’s late boyfriend Gordon Matta-Clark) Heilmann has painted a square canvas in bright yellow, then covered the yellow in ultramarine blue. With the blue layer still wet, she wiped off a border to reveal a yellow frame around a central blue square. She has said of ‘Gordy’s Square’, ‘I wasn’t really thinking about painting, I was thinking about structures’. In literal terms the painting was made as a simulation of Matta-Clark cutting through layers of a building, more formally the canvas surface is not only a two-dimensional picture plane but expands into space and becomes a physical thing. There is a sense that all of Heilmann’s paintings are objects, and that the stories of their form derive from what has ‘happened’ to them during the process of their making.

“Music of the Spheres”, 2001, Oil on canvas, 76.2×116.8cm, ©Mary Heilmann; Photo credit: Hauser & Wirth, Courtesy of the artist, 303 Gallery, New York, and Hauser & Wirth

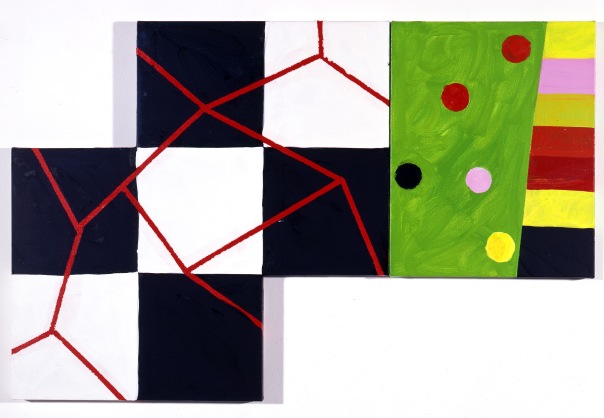

Heilmann’s journey to establish a personal language of painting is explored well in ‘Looking at Pictures’. The first half of the exhibition shows paintings that are experimental, characterised by enquiry and new ideas. In the upstairs gallery, however, the pace slows and Heilmann’s approach feels wholly established. The gestures that felt fresh and rebellious in the 1970s and 80s appear fixed and more formulaic in the 1990s. By this point her colour palette fully embraces her inspiration in the saturated pop colours of Californian sunlight and TV cartoons such as The Simpsons, not straying into new territory until the more muted works descriptive of roads and ocean waves at the end of the exhibition. There are fewer questions being asked – more answers being stated over and over again. Titles and narrative associations become increasingly personal, and humour is more pronounced, for example ‘Good Vibrations Diptych, Remembering David’ (2012), where colour extends from the edges of the canvas in the form of ceramic wall mounted shapes, venturing close to pure whimsy. The freshness of Heilmann’s attitude is restored in works like ‘Johngiorno’ (1995), in which a web motif covering part of its surface jolts the painting out of flatness and into an implied dimensional space alongside a flat rendering of loose, coloured dots. Heilmann has said of this, ‘the pattern in Johngiorno is like cobblestones. The adjoining of two different motifs represents a collage aesthetic, which is important in my work… In other works, especially my shaped canvases, I join different motifs together.’ This forced affinity of difference is one of the recurring themes in Heilmann’s work. She brings together a personal lived experience of memory and connotation with a relaxed formal abstract language of irregular grids, sliding squares and wobbly edges. The adjacent positions of private and public / studio and gallery are implied in the physical exhibition space through the inclusion of Heilmann’s brightly coloured chairs. They add nothing to the paintings but contribute to the overall sensation of colour coming off the canvas and into the real world, and this shifting between two and three dimensions has been embodied in her practice for the past 50 years. ‘Looking at Pictures’ shows clearly that Heilmann’s journey to this point has not been a singular experience but several running simultaneously. Her more recent paintings such as ‘Maricopa Highway’ show that she is still moving, and that there is still more than one direction of travel to explore.

Seems to me that about a decade ago Heilmann gave up on taking the piss out of abstract painting (probably because fashionable abstract painting had itself become too loaded with irony to take the piss out of) and started taking the piss out of her own memory-bank of personal images. What sort of a pathetic painting is “Maricopa Highway”?

Her paintings are worth looking at for about the same time as each image in her slide show is given – about eight seconds. Don’t know why she bothered with the chairs.

LikeLike

I don’t completely disagree with you Robin. Certainly the chairs don’t really contribute anything to the paintings, in the same way that the ceramic wall pieces in ‘Good Vibrations Diptych…’ seem quite inane to me. The second half of the show does reveal the limitations of Heilmann’s work, becoming too self-referential and overly reliant on her already established motifs; there was nothing that felt new until the final paintings, of which ‘Maricopa Highway’ was one. I thought these later works were less formulaic and maybe did a better job of bringing together Heilmann’s abstract shorthand with her autobiographical impulses than did the works from ten years ago that relied on repeated geometric symbols and subjective titles.

I’m interested in what you think of Heilmann, or anyone else for that matter, ‘taking the piss out of abstract art’. Is that necessarily a bad thing?

LikeLike

There´s a place for taking the piss out of abstract art, but whether it happens visually or verbally it is criticism/satire and not art. “Little Mondrian” would be a poor cartoon in a lifestyle magazine. Putting it in a gallery and selling it as art is a kind of category mistake.

LikeLike

A general thought that if the value of a painting relies on ideas, concepts, philosophy instead of its visual quality one wonders why anyone would want to paint it in the first place. If your going to provide something of worth to engage with visually ‘as well’ then fine. Ironically, or indeed absurdly, some try to generate ironic meanings in a ‘visual’ work of art. This is doomed to fail, in terms of offering anything of value to spend time with.

LikeLike

In my ignorance I have never heard of Mary Heilmann or knowingly seen any of her work, but I feel she must have some kind of huge reputation to be showing such frankly seemingly weak work in a prestigious London gallery or any other gallery! Not everything a renowned artist paints is necessarily good, I don’t feel the quality of these works matches up to Charley Peters’ fine, articulate writing in any way. Perhaps her other work is much stronger, I am only reacting to the paintings shown here.

LikeLike

Charley,

Thank you for your essay and your comment. I have no doubt there is a place in this world for piss-taking and its enjoyment, and the art-world is ripe for it. But the joke is short-lived and tired, just as Heilmann’s paintings are transitory, familiar and boring.

One of the problems is that when works like Heilmanns receive praise for their wit and ingenuity, it downgrades the expectations and ambitions of other abstract artists; so that now, any number of painters think that slapping a few lines and shapes around on a canvas, in a manner that vaguely represents something or other – place, memory, feeling, whatever – constitutes an abstract painting, in which it is the very ambiguity of the work which constituting the “abstract” bit. Maybe in itself, for the individual, this is not a problem – until this mannerism becomes ubiquitous. Then it becomes dangerous, because a vision of something bigger and better is lost.

We are at a time when a re-examination is newly underway of how abstract painting and sculpture is thought about, and how every part of a painting or sculpture might be seen to contribute fully and specifically to a whole (I refer, of course, to Brancaster Chronicles!). This is happening in the teeth of the general consensus that skimming the surface of painting’s tropes – or indeed, skimming the skimming – is actually enough. The misconceptions about abstract art now go wide and deep; Heilmann is not actually abstract at all – she’s either literal or she’s figurative, or sometimes she’s both (as in “Maricopa Highway”). And both those conditions are denials of a truly abstract art and its fantastic potential to be as ambitious and brilliant as any other art-form from the past.

The thinking around abstract art undoubtedly becomes blurred by the lack of seriousness shown by Heilmann and others in the spotlight – a seriousness which of course could include humour, like any other human value, provided an original way is found to embody such values in the physicality of the work, and not just reproduce them as a banal image/idea. Last year I wrote on this site about Richard Diebenkorn and his contribution to what I described as the “hollowing-out” of painting. Heilmann is probably a much worse example than Diebenkorn, though in the end there is not a huge amount to separate them in their individual contributions to the shallow aesthetics of a great deal of contemporary art, despite their approaches being so very different.

Over on another comment stream, Jock Ireland is berating me thus: ‘Robin, you are in trouble—or you seem to be. You seem to think art is a problem to be solved by being more “abstract,” or by being “new,” or by making “progress.”’

Well, yes, I do; and abstract art is in trouble, thanks both to painters like Heilmann, and to the relaxed and unfocussed thinking of many observers on the sidelines, including intelligent people like Jock. And I’m happy to buy into that trouble, and forgo the assumed entitlement to modernist “ease”.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I was interested in hearing thoughts on piss-taking as I see Heilmann’s early baggy ‘abstraction’ and personal narratives as, at least in part, a response to the authoritarian, macho point of view of Greenberg et al. I think that this had validity in the early 70s as a counter position. But you are right in saying that this is more of a transitory gesture and not a sustained or meaningful practice. I actually don’t believe that Heilmann’s work is abstract in any pure sense at all, which is why the later works like ‘Maricopa Highway’ feel more like an honest positioning of her painting than most of the work from the 1990s; more openly figurative and less reliant on the knowing application of well established visual effects.

In reference to concerns about the crisis in abstraction, where should the responsibility of the artist lie; in challenging what is happening now, in shaping what comes next, in both or neither? Can we afford artists the freedom to explore shape, form, materials etc in order to question the language of abstraction yet hold them accountable when a visual language becomes fashionable, mimicked or ‘hollowed-out?’

LikeLike

Re: your last sentence – what a very interesting question. Artists need space and liberty to make art (and make mistakes) and you can’t make art from a rigid, undeveloping theory. A further question is: when does a “free” attitude to art-making become an indulgent liability that’s just as bad as a rigid system or theory?

LikeLike

All the abstraction I see on line being done whether in the UK,USA or Australia is Heilmanesque. The casualist/provisionalist style is universal. Have to hand it to Mr Peters for writing about her work as a direct response to what was in front of him without delving into theory.Art criticism needs more writers like him who bring a “negative capability” to their writing on art. I am incapable of that evenhanded approach. The more authoritative,theoretical art that Greenwood espouses still has a future despite what many people think, whereas judging from the influence of Heilman on the younger generation there is a dead end quality about it.I think I will label her the founder of the “Shake and Bake” school I wrote about.http://martinmugar.blogspot.com/2016/05/shake-and-bake-aesthetics-in.html

LikeLike

Not sure I can see the “wit and ingenuity” – or even that I want to. Will have to visit the show now!

LikeLike

Visited the show yesterday. I get the “wit” now. Still not sure about the “ingenuity”. Superficially, Heilmann’s paintings look abstract. I don’t have a problem with the links between her lived experiences of people and places – although it feels rather shorthand. The slide show was entertaining.

As for the “piss taking” – is the artist ‘extracting the Michael’ out of ‘contemporary’ art by design or default? To be honest, I don’t know enough about Heilmann’s personal intentions – but if the work gives this ironic impression to some viewers there might be something in it. Maybe there is a Simpson’s world-view here – full of irony and sad misgivings, with a little humour, about modern life in America (and beyond); and healthily lambasting our own human failings. Is art in any form, abstract or otherwise, doomed to be re-presented in cartoon-like form these days? (Not on AbCrit, of course!) Are these cartoon (in the modern sense) abstractions? Is Heilmann being disingenuous as a comment on modern living?

Actually, I quite enjoyed visiting the show, despite the fact that there were only two or three that I really liked and could have taken home with me. But then I would rather have a Mondrian or a Matisse on my living room wall!

LikeLike

Here’s my two pennies’ worth on art and “anything-goes” (with no claim to originality or joined-upness)

I think that the essential property of art is to transcend (or by-pass) material, objective culture and communicate aspects of being that cannot exist in that culture since they cannot be objectified and made amenable to rational public discourse…

(I think that we can all know when this communication takes place and so we can all recognize art. It doesn’t have to happen for everyone at the same time and with the same work. It’s a subjective rather than an objective, provable judgment, but I think it is nevertheless widely interpersonal.) ….and any painting or sculpture that doesn’t do that (or doesn’t even want to do that) is better described as visual discourse (part of our objective culture) than as art.

Existence is an ever-present wonder that we simply overlook for 99% of the time, so embedded are we in our minutely constructed and dependable objective world. Everything that lies outside of the quantifiable, rationally describable, conceptually straightjacketed, technological world we mostly inhabit is deeply mysterious. Art, however imperfectly and incompletely, can communicate something outside of objectivity. It has always been associated with magic, spirituality, altered states of consciousness ( “ma petite sensation”) and other aspects of irrationality. It reminds us of the mystery (not some way-out, esoteric thing but the very ordinary, ever present fact of existence) and helps us to an awareness of our non-objecthood – the fundamental independence from any objective description that is crucial to our humanity.

It has nothing especially valuable to contribute to the objective world view. “Political art”, “conceptual art” and all the other forms of context- and theory-bound “art” are (to my mind) illustration, propaganda or some other kind of visual explication or discourse but not art.

Art is nonetheless political. It is one of the last refuges for a cultural alternative to the dominant rational scientism that sees only repeatable causes and effects, uses, costs and benefits, and is beginning to believe that humanity can be replaced by a digital reconstruction to be sent into space.

The attempt (by Danto and others) to reduce art to “anything that the maker or a curator professes to be art” is an attempt to drag art into the objective world. It sounds wonderfully democratic (“everything can be art”) but by neutralising the subjective judgment of art (which is open to everyone) it allows the market and a curatorial elite (the world of money and power) to step into the vacuum and determine value, thereby also frustrating the other democratic promise that “everyone is an artist”.

It also allows a whole lot of stuff that utterly fails to transcend material, objective culture to be hailed as art. And since it is this kind of “art” with its theories, investigations, positions, thematisations, messages, references etc. that is easiest to talk and write about ( precisely because it lacks any transcendence), it is also this kind of work that colleges can teach, galleries can push and curators can publicise most easily.

Funnily enough, the written word has far fewer problems and inhibitions distinguishing art from commentary, journalism, polemics, theory, instruction etc. I don’t think anyone would want to maintain that claiming a random piece of writing to be art is sufficient to make it art. Any kind of knowing, ironic attempt to sell a physics textbook as literature wouldn’t even be laughed at, it would simply be ignored.

That isn’t to say that there’s not an important role in society for all the visual equivalents of these non-art forms of writing – most of them would be forms of illustration, some of them brilliant forms of illustration, but contemporary society regards them (on demand) as artworks.

It may well be that the struggle for the everyday meaning of “art” has already been lost to Danto and co.

For me, that is the importance of institutions like abcrit and Brancaster, where a similar struggle can be carried on one step further down the road – with the term “abstract art”. Here, literalness, contextualisation etc. can be condemned without offending the “everything is art” principle, so creating a safe area to keep out the hordes that have been let in elsewhere.

For me there’s a bit of baby and bathwater in this, because I think that figurative art too can still deliver the goods. But then the small Armorican village of abstract art is maybe easier to defend than the whole of Gaul.

As to the methods of artistic communication, I think there really is complete freedom. Whatever works is OK. The only method that can never work is the deliberate attempt to communicate something particular, since that leads directly back into the illustration of an idea.

As an artist you have to be engaged in something that reveals rather than describes (Heidegger’s “unconcealing being”). Irony and taking the piss are ruled out from the start.

Just-being-there is one way of communicating subjectively, though maybe somewhat limited and anyway it’s rude to stare. (Lovers can stare at each other and lovers are acutely aware of subjective being.)

Following tradition is another – artistic tradition provides us with a variety of tried and tested conventions which do not determine any content, just set up a framework that is conducive to subjective communication. These have worked for many artists, without seriously impinging on their individuality and as they are a common good they also facilitate reception.

The quest for non-literal spatiality in sculpture (if I’ve understood that correctly) could be seen as one such activity.

For the rest: Yes, anything goes. Do something completely different – but if it doesn’t work, it’s no good decorating it with some kind of objective explanation and the all-purpose excuse that “everything is art”.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Good post- thank you.

LikeLike

I like some of what you say Richard, although I wonder about trying to argue against the “everything is art” position. I have given up arguing that something isn’t art. What I do find myself doing is asking whether something defiiend as art has any positive, interesting valuable meaning. What purpose does it serve? In terms of Mary Heilmann’s work I would want to ask these types of questions.

I like the idea that a kind of painting and sculpture that seems worthwhile pursuing these days does indeed “transcend (or by-pass) material, objective culture” and communicate aspects of being that cannot exist in that culture since they cannot be objectified and made amenable to rational public discourse…”

This resonates with some of what Alan Davie said in his notes at the time of his retrospective at the Whitechapel Gallery in 1958:

“If a work is to be of any value it must convey something which transcends material.” Critical in these notes about his work being described as ‘action painting’ he argues for a work having an existence of its own, and in some ways separate from the ‘process’; “Our painting does not [my emphasis] convey the drama of the moment of creation.”

There is a lot of stuff in these short notes worth thinking about:

“Perhaps a better term for our purpose would be “Non Act Painting” implying more accurately that the true artist is basically against acting and that he accepts the relative reality of existence and therefore not infatuated by the image of himself above it.”

This seems to be a sort of political, non-hierarchical statement.

On your views on the political in art there is something to further explore here.

The politics of the art world which seems clear is related to exhibiting, selling, critiquing, collecting, viewing, and is inherently hierarchical and unequal.

The political nature of the work itself is another question. For me is this where some kind of ethical view of the freedom of both artist and viewer is of paramount importance. Whether the ‘freedom’ of the art work (object) itself makes any sense is another point to ponder. Abstract art in particular seems to me to still be a crucial place to express and explore one’s freedom and indeed resistance to a society which demands a levelling down and a reduction of the possible, unless it serves the status quo.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you John B, for empathising, and John P for seeking out what might be defensible within my outpouring. Are the Alan Davie notes available anywhere online?

LikeLike

John H not B, sorry.

LikeLike

Richard, I haven’t seen them on line but I’ve emailed you the nites in two jpegs.

LikeLike

There were some good paintings in this show, though its meandering curatorial agenda, stressing context, career development and personal profile, overrode its aesthetic focus.

Heilmann came over as a strikingly adequate painter. Despite the colours, she’s no colourist. She’s more interested in contrast and less in complex chromatic interactions or warm/cool distinctions. Only one colour was modulated or adjusted in situ, the dullish grey/mauve in ‘Primalon Ballroom’ 2002, which misleadingly reproduces on screen as violet.

She’s comfortable revising the hidden or overt grid format and recycling compositional devices, fitting forms into the confining, facing surface of the tablet-like supports, but not insisting on geometric perfection or pure relationships. Though common property, she seemed to own rather than borrow the lexicon of formal elements. They looked homemade and were not deployed in any ludic process of appropriation or commentary, references to Matisse and Mondrian being rather half hearted.

About an hour into my visit however, I found it difficult to shake off a worrying thought; it was an exhibition of paintings, but not of art, even post-modern art. I think this was because the work lacked what might be called ‘pretence’. By pretence I mean ‘the attempt to make something that is not the case appear true.’ With Heilmann the work is the case, materially undeniable and stout, like pottery, her former pursuit. It does not claim anything beyond itself.

So much current art can be criticised as pretentious – making excessive claims to merit or importance – that work in which pretence is absent may be a welcome alternative. But pretentiousness is a different issue. In Heilmann’s work there’s no pretence of pictorial or colour field space, of the significance of an underlying geometric order, of philosophical or religious meaning, or of the sublime, or self-expression, of the unconscious, of irony, or art history, of art theory, or of minimalist or constructivist ideology. These are features that animate paintings within the tradition of abstraction to which her work seems to belong but that maybe aspire more ambitiously than hers to be seen as art.

The upcoming show of Abstract Expressionism should be an interesting comparison. The artistic ambitions of that group might be satirised and ridiculed but hardly denied. All of the above concerns that Heilmann avoids figure in the claims that could be made about their paintings, claims that might be seen as overblown or pretentious nonsense. And such claims may not be the case, but that does not matter too much. The point is that typical abstract expressionist work is characterised by pretence, by an effort to make what is not the case appear true. Pretence spins painting into art.

LikeLike