Lee Krasner, “The Eye is the First Circle”, 1960, oil on canvas, 235.6×487.4cm. Courtesy Robert Miller Gallery, New York. © ARS, NY and DACS, London 2016 Photo Private collection, courtesy Robert Miller Gallery, New York.

“… Like a Tongue to a Loosening Tooth.”

Thoughts in anticipation of the upcoming Abstract Expressionism show at the Royal Academy, 24th September 2016 – 2nd January 2017.

“…It seems that I cannot quite abandon the equation of Art with lyric. Or rather – to shift from an expression of personal preference to a proposal about history – I do not believe that modernism can ever quite escape from such an equation. By “lyric” I mean the illusion in an art work of a singular voice or viewpoint, uninterrupted, absolute, laying claim to a world of its own. I mean those metaphors of agency, mastery, and self-centredness that enforce our acceptance of the work as the expression of a single subject. This impulse is ineradicable, alas, however hard one strand of modernism may have worked, time after time, to undo or make fun of it. Lyric can not be expunged from modernism, only repressed.

Which is to say that I have sympathy with the wish to do the expunging. For lyric is deeply ludicrous. The deep ludicrousness of lyric is Abstract Expressionism’s subject, to which it returns like a tongue to a loosening tooth.”

TJ Clark, “In Defence of Abstract Expressionism,” Farewell to an Idea.

The RA blockbuster autumn extravaganza promises to seduce us with its knock-out line up of Abstract Expressionist paintings in its lofty neoclassical halls. But scrape beneath the veneer of showtime spectacle and the history of this movement is a battleground of interpretation. It is littered with the burnt out wreckage of a thousand blood-thirsty intellectual engagements between titans of art history from the Left and the Right. By comparison, art making now seems to operate in the uncanny silence that has descended on an ideological no-mans land. But first, please forgive a digression…

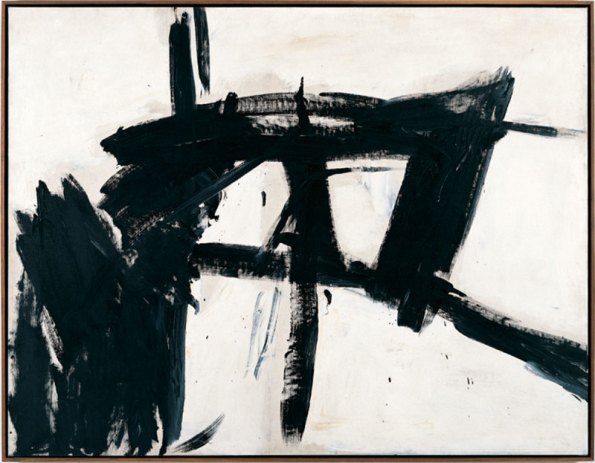

I was asked to attend and talk at a symposium on John Hoyland’s legacy earlier in the year. It became clear to me how much of this afore-mentioned ‘wreckage’ I was determined to drag along to the proceedings, whilst other older and younger participants seemed to maintain a much more bright and breezy approach. Older artists and commentators talked of ‘late manners’, younger artists talked of Hoyland’s cosmic dream spaces and the sanctuary of the studio as an escape from the blight of social media. I found myself coming back time and again to the implications of the legacy of Abstract Expressionism and how it had been dealt with by the later generations, but especially by the likes of Gerhard Richter. I think Richter has successfully reinvented history painting via photography. But he has failed to reinvigorate abstract painting to anything like the same degree. Take the Cage paintings for instance. They court the idea of chance and contingency by referencing the name of the avant-guarde composer John Cage. By dragging layers of paint across canvases Richter reduces the tantalising suggestiveness of gallons of oil paint to the vague outcomes of repetitive physical actions with a squeegee. One also has to take the word ‘cage’ on its own terms too. A room of these paintings conjures the sour self referential painterly prison in which the painter whiles away their hours. Painterly invention happens as a byproduct of Richter’s almost forensic investigation via painting of an historical photographic image. Yet in abstract painting, he only seems capable of producing simulations and sometimes beautiful accumulations and debri via his ‘process’. One commentator at the symposium told us that Hoyland lived by the refrain “I paint therefore I am.” That’s all very gung-ho but it was Richter who pointed to a peculiar duality at the core of the endeavour of painting. He focused on the tension between doubt and belief in painting – he once called painting “pure idiocy”. Of course, this quip references Duchamp, who took great pleasure in goading painters. If Hoyland seems to have readily embraced Clark’s “ludicrousness of lyric” (especially in his ‘late manner’) then it’s Richter who personifies the desperate need to ‘expunge’ it.

I mention all this not because I want to imagine Abstract Expressionism somehow magically liberated from the wreckage or the baggage of so many dichotomies, false or otherwise. But we are are so used to the narrative of the terminal downward tail-spin in painting, the ever decreasing conceptual circles and Duchampian conundrums for which Richter is a famous exponent. And we are also used to the clichéd view of painting inspired by Abstract Expressionism as the narcissistic outpourings of some heroic macho individual ego. How do we resist Clark’s attempt to cast the Abstract Expressionists as a mid 20th-century strain of decrepit bourgeoisie, acting like an artistic version of a suicidal aristocracy?

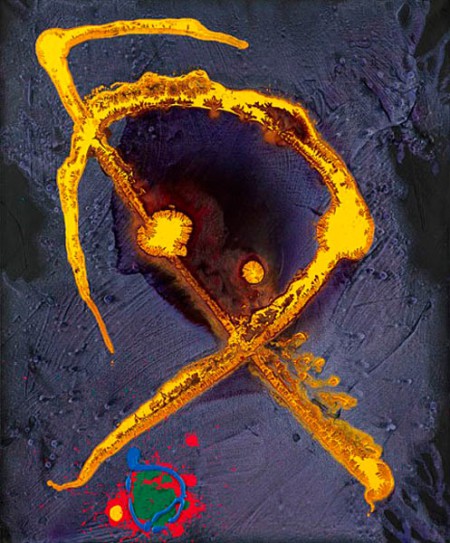

Clyfford Still, “PH-950”, 1950, oil on canvas, 233.7×177.8cm. Clyfford Still Museum, Denver © City and County of Denver / DACS 2016 Photo courtesy the Clyfford Still Museum, Denver, CO Photo: Courtesy of the Clyfford Still Museum, Denver, CO © City and County of Denver.

Abstract Expressionism and it new found painterly inventiveness whipped up the original and epoch-defining perfect storm of cultural criticism. But a storm’s energy is driven by the collision and the channeling of opposing physical forces. And this particular mid 20th-century strand of abstraction operated with a myriad of contradictions at its very heart. At once, it seems to pivot on an idea of the trenchant individual, as Clark points out. On another level the work begins to involve the notion of field-painting as an immersive experience aimed at encouraging the active engagement of the viewer’s own physical and psychological projections. For some the very idea of the individual was a welter of opposing desires and drives looking for some kind of revelatory cohesive expression in ‘the here and now’, in the special and peculiar qualities of paint liberated from the strictures of its European heritage. Yet Abstract Expressionism leans on notions of the timeless and mythological, the doom laden and the tragic. At the same time, though, it is supposedly the genius of a thoroughly new nation. Young and naive, its creativity was unhindered by the old world of power-hungry empires. For a while it stood in direct opposition to the perceived deathly grip on art of decadent Eurocentric cultures, enslaved as they were, to inbred and ossifying aristocracies. Greenberg and then Fried argued about points of continuity in art history, the baton of advanced art handed from Paris to New York. Clark talks of rupture and the the distorting effects of American capitalism as a defining characteristic of Abstract Expressionism. Serge Guilbaut explored America as a rising expansionist Empire in its own right, exporting its new art around the world as a ‘soft power’ influence and cultural bulwark against the Soviet threat.

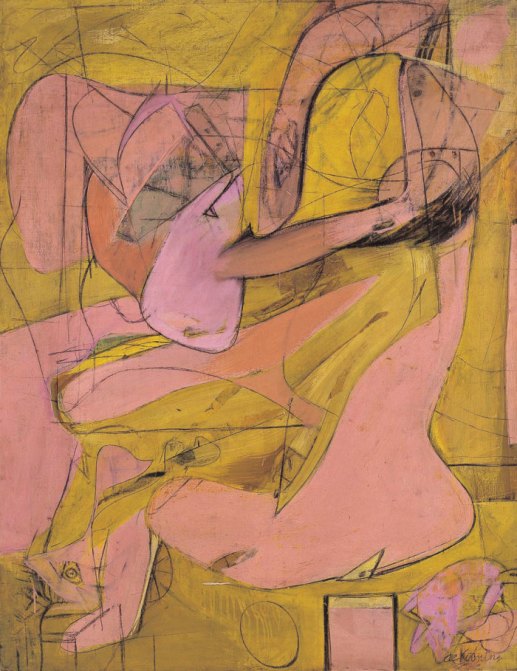

Willem de Kooning, “Pink Angels”, 1945, oil and charcoal on canvas, 132.1×101.6cm. Frederick R. Weisman Art Foundation, Los Angeles. © 2016 The Willem de Kooning Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York and DACS, London.

Originally, of course, there was the very public war between Greenberg and Rosenberg over the true meaning and future of Abstract Expressionism, which is almost legendary. But there were other less shrill and possessive voices that are still echoing quietly through history, if one is prepared to listen. If we see this new American art as Meyer Schapiro did during this period then it becomes “….a social bond that furthers in aesthetic terms the process of human self-realization through the non-instrumental refinement of the senses, and through the critical engagement of the intellect…” Schapiro’s Marxism was dialectical and nuanced rather than purely economic and materialist. His anti-Stalinism was shared by many of the Abstract Expressionist who had turned their backs on the Socialist Realist art extolled by America’s ailing Communist party. They refused to reduce society to an oversimplified marxist model of a ‘base’ as purely economic and superstructure as just a cultural add on. They believed culture to be as important and integral to a healthy society as economic stability. Schapiro was also determined to highlight the connections and dialogues between art making and the social realms in which abstract art and artists existed. It is in this spirit that I believe a deeper and complex view of the legacy of Abstract Expressionism can develop. Just maybe, this might be a way forward – a way to embrace these artworks anew. It is easy to see them now as art historical monuments, fetishized and reified – drowned in the gallons of ink spilled in the attempt to apprehend them and bend them to whatever ideological ends. If we see history, like many of the Abstract Expressionists did, as a perpetually contested realm, the future always born of the ferment of these contestations in the making of art – in the living of life – then the artworks that constitute Abstract Expressionism are more than just another brand of formalism or heavy breathing machismo or the “ludicrousness of lyric”. Enjoy the show.

When I see this show I want to start with looking. The broader history, politics and views of the critics can wait.

LikeLike

Come on Geoff – it’s very on-trend to get your political critique in early. What is it you want to look at?

More like “The End of the Line”. Are we still interested in this stuff? I suppose I’m looking forward to one or two early Pollocks and the Krasner, but I can’t help but feel, looking at the other illustrations to this essay with a rather sinking heart, that the tooth has fallen out a long time ago, it’s rotting under the pillow, and a lot of artists have deceived themselves in the vain hope that the tooth fairy of minimalised spontaneous expressivity is going to materialise sometime soon. Personally, I’m looking forward more to the Rauschenberg at Tate than I am to this, though I could be severely disappointed there too. But at least he occasionally had an “eye” for things, and a bit of vitality.

So here’s a challenge: we know the Richter and the late Hoyland are crap. So someone tell me the good qualities and values of the Rothko or the Still illustrated here, and why they are any better. No contextualising or generalising allowed. And definitely no French philosophy. Stick to qualities within the individual work. Good luck.

(I can sense Alan G. saddling up his very high horse on the top terrace of his vertiginously tall ivory tower right now. Steady, Alan, it’s a long way down.)

LikeLiked by 2 people

I want to look at everything – and today I did. I also had a chat with Stephen Buckley in the pub later on.

LikeLike

I tend to agree with you. What you see is what you get. If you begin with this in mind you’re less likely to feel short changed.

The context in many cases can confuse but often add interest.

LikeLike

I think it might be more important than ever to call a lot of this work out for what it is, and I don’t mean to sound disrespectful. There is much to be admired, but also a lot that fails to live up to the hype. I was recently in the States and saw quite a bit of Rothko and Still. I found the colour in some Rothkos, particularly at MoCA in LA, to glow and pulsate (though you could ask for more than that), and I did marvel at times at his preparedness to take his idea that far. But other times I wondered why he had to paint so many of them. The Clyfford Still room at SFMoMA helped me to decide that I wasn’t interested in Still’s work. It all looked very stiff.

A lot of the time I think the problem is what gets shown. We are supposed to believe that this was a radical time of experimentation but so many major museums seem to just angle towards the most obvious and iconic works, so that the general gallery going public have every chance at being able to recognise who did what, take the obligatory selfie, tag the institution and perpetuate the flow of people into the museum. The same could be said for a lot of the older figurative art shown, but there is something kind of tedious about the iconicism of the “distinct styles” that the 50s work offers. Is there not something so predetermined and cute about a signature? The quasi-surrealist line work in the above de Kooning, say?

It seems important to be critical of much of this work now because painting, particularly abstract painting, is cool again. And yet everyone just seems to be repeating all this 50s stuff, or Richter, or Bauhaus, (stuff which might not have been that flash the first time around) without even seeming to recognise that is what they are doing. I don’t mean to can a whole period of important painting, rather express my disappointment with some of the more famous works from that time and a current milieu that seems destined to waste a lot of time doing the same stuff, almost unawares.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Re: “A lot of the time I think the problem is what gets shown.”

Good point. I like looking in those Christie’s sale catalogues and seeing the work that is in private collections.

LikeLike

This from the self-penned catalogue essay from the show “Alan Gouk: New Paintings” at Poussin Gallery, 2012:

“It has been the self-engendered, if at times poorly understood destiny of my generation of painters to bridge the gulf between the ardent spirituality of the Abstract Expressionists, with all their rhetorical excesses, and the over-cool design-conscious aesthetic of the post-painterly generation – a destiny which has been grasped with varying degrees of clarity and steadfastness. Why Patrick Heron has been so crucial is that he was one of the first to put his finger on the flaws, both of the Abstract Expressionists’ brusque advertised spontaneity (when present), and the distanced decision-making at a remove from the flow of the painting process of the first phase of post-painterly abstraction (the later Olitski and Poons are partially exempt). That is, until the reappraisal of Matisse/Picasso which began in the 1980’s and was given new impetus in 2002 by the Golding/Cowling version at Tate Modern, rendering the whole American intervention almost irrelevant.”

A really interesting passage from Alan, and I concur with the sentiment of the last sentence – that the contribution to painting of the Americans is overrated, particularly by comparison with Matisse. I would go further and say that (perhaps Hofmann apart) these works are going to prove to be less and less important in the future. But what’s also interesting is Alan’s contradictory and compulsive belief in an unchallengeable destiny, in which he has to participate with “steadfastness” in bringing together what he admits to being two rather dubious idioms of painting, simply in order, as he sees it, to be of any account as a painter now. This is his fate, it seems.

But this linearity is the thing that has to be broken; it’s the thing that prevents better progress and understanding in abstract art. If you swallow whole the meagre offerings of painters like Rothko and Still, the chances are you’ll never get very far beyond their limited aesthetic. And one thing the Americans certainly didn’t do for abstract art is invent for future generations some developable and substantial abstract content. What little content there is stops dead at the point where their individual signature styles die, along with the artist. Good for the art market, bad for art. Bring back John’s “perpetually contested realm” by all means, but let’s not contest the value of these dead paintings for too much longer.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I am flattered that Robin feels it necessary to drag me into these controversies, which are more controversies of criticism and interpretation than they are of fact, and that he is so obsessed with my writing and his “compulsion” to disagree with it, nit-picking in order to find a way of inserting his Knife of bile wherever he can. It is all too easy for someone who is determined to erase his own past, and deter people from access to it, to forget what it was like to live through the 1960s and 1970s , when first the A.E.s and then the post painterlies were omni-present in every aspiring artists consciousness, like it or not. And utterly disingenuous too to overlook the extent to which my writings in this period and subsequently were among the few cogent critiques of the prevailing assumptions of the discourse which surrounded the painting (and the sculpture, later). But of course you wouldn’t know that from the way Robin paints it. You’ld need to do your homework.

Patrick Heron’s critique, which began at the first sight of the 1956 Tate show of the A.E.s and escalated through the 1960s with his spat with Greenberg, is well known and has the advantage over all the colourful phraseology and “extravagant prose” which Greenberg so effectively pilloried, of being by a painter who knew a thing or two from the inside what the pressure of the historical moment was, and why these painters could not just be swept aside with some glib nonsense about “abstract content”. Remember that the A.E.s had begun with the “Subjects of the Artists” manifesto and polemic, and we’re trying to “put in” subject-matter, misguidedly of course, rather like trying to “put in” content.

Most of the discourse since, and up to the present, has been just that, extravagant prose, righteous phrase making and colourful socio-political wiff-waff. Heron addressed the painting directly as an engaged painter, and cut through all that. I fear we are destined for a lot more wiff-waff, with Robin’s bigoted attacks On everything modern at the helm, on this site as well as in the media at large. T.J. Clark’s self serving and arrogant intro is a locus classicus of self satisfied and self advertising rhetorical excess. So there’s a tradition to be followed, an easy trap for the would be pundit of post modernism. Linearity schminearity.

,

LikeLiked by 1 person

And as for Rauchenberg, we all saw through that one way back in 1964. Reminds me of ” not since Jasper Johns’ final literalisation of the canvas surface has a painting’s meaning been looked for in its unmediated visual qualities” or some such. It goes to show how astray ones powers of perception can be led by a programmatic agenda, cock-eyed and conceptually wrong headed. Rauchenberg – vitality? You must be joking.

LikeLike

I don’t know why you think these paintings need defending. They need no defense from me. There is nothing I could say that would make them any more palatable to the prejudiced eye. They can speak for themselves.I can’t believe we are still going over the same old ground. If anyone wants to know what I think about the A.Es –see my Letter From NewYork, one of the first articles on Abstractcritical in 2011?

However, what they do need defending from is yet another salvo of anti-modernist invective from the purblind apostle of the nearly-new — deeply reactionary stance masquerading as radical (how many times have we seen that in the past). Again I am forced to reiterate Rohko’s statement — ” a painting expands and quickens in the eye(or mind) of the sensitive observer. It dies by the same token”.

Meanwhile over on Brancaster, participants are obliged by the nature of the FORMAT ( microphone and video broadcasting to the world) to rationalise and defend their work even before it has cooled down.

If a work is successful the artist should not be able to say why or how ( not for a while at least). It should be as much of a surprise to them as it is to others, and no easier to rationalise, (as seems to have happened with Mark).

As well as giving over-attention and praise to work that doesn’t merit it, you are intellectualising and analysing to death work that doesn’t require it. A simple value judgement, approval or disapproval would be more effective and useful to the participant. It’s all coming from the wrong place. The work is one thing, and it’s rationalisation quite another, except when the latter is interfering and messing up the former. Too much of the mind in all of it, Mark and Hilde excepted.

Hasn’t it dawned on you yet that the more you refine your conception of “abstraction” , to the point of damned near refining it out of existence, the more your verbalisations could equally well apply to art the very opposite of anything you would want (unless of course Rauchenberg is your bag).

LikeLike

Mmm… “simple value judgement, approval or disapproval”… now, do we know anyone supercilious enough to do that, I wonder…?

LikeLike

Alan’s article here: http://www.abstractcritical.com/article/letter-from-new-york/index.html

LikeLiked by 1 person

I always found it helpful to understand Rothko in terms of Husserl’s eidetic reduction. Husserl was trying to pin down where reality was located and found it made sense to place it in our cognitive apprehension of the world. It is in the eye/mind’s apprehension of the world .Heidegger took issue with this by saying this perceiving subject is already in the world and that being-in-the world takes precedence over the structure of the perceptual apparatus and how it structures the world. I think this points to why Rothko is sometimes seems less appealing to the public than Matisse.Rothko’s painting is a too pure reduction of color logic and leaves out the world in which the artist moves.Matisse as he moves toward to purity of the cutouts is still a being among other beings or things and the cutouts still refer to bodies. Rothko is too much like a visit with the audiologist where you are asked to identify pure sounds in order to evaluate the quality of your hearing.The test will determine weather you are losing hearing or not but has nothing to do with hearing as it is used to create a world/space for the hearer. This reductive aspect of Rothko creates in me a lot of anxiety as what is left out of this reductive trope begins to grate on my sensibility. It is interesting to see how this exquisite dead end is pursued further by Ellsworth Kelly who separated pure colors into sculptural objects and then drops the color completely to just exhibit the plywood substrate that supports the colors.Digging a deeper and deeper hole of nihility. Ellsworth is still serious unlike the Zombie Formalists and the Provisonalists who deal with High Modernism as a commodity or with irony. However, they all thought highly enough of Modernism to deconstruct it, negate it or laugh at it.I deal with its lingering life here:http://martinmugar.blogspot.com/2013/12/zombie-artthe-lingering-life-of.html

LikeLike

Martin, I’m interested in what you say about the ‘anxiety’ you have with Rothko. It reminded me of an essay from the 70s by Lawrence Alloway concerning the “Residual Sign Systems in Abstract Expressionism”.

“…The term “gestural” is commonly applied to Abstract Expressionism with reference to conspicuous brushwork, but the term is also applicable to those of Newman’s paintings in which the whole work has a gestural function. The tall lines and man-sized area are a kind of gestural condensation……”

Although Alloway is talking about Newman here, I like the way he makes explicit the role of the ‘gestural’ and how it is absorbed into the painting surface by Newman and Rothko. Over the years I’ve spent a fair bit of time with the Rothkos at Tate. Not only in colour but in its application, the paint is creating tidal undertows- riptides and counter rhythms. For me they create in combination a very corporeal space full of slow and bloody undulations.

I think the best Ab Ex paintings somehow conflate a sense of interior or corporeal space with an exterior reality- the reality of the picture plane- in a very visceral and bodily way. Greenberg put like this…

“The best modern painting, though abstract, remains naturalistic to its core, despite all appearances to the contrary. It refers to the structure of the given world both outside and inside human beings.”

The Role of Nature in Modern Painting Partisan Review 1949. P 81

Like you Martin, I’m interested in what separates, say, Rothko and Newman from the likes of Ellsworth Kelly and Frank Stella. What is lost in translation between generations? And then, what is gained by ,sometimes, willed ‘mis-reading’?

Alloway goes on to say…

“Contrary to the notion therefore that the Abstract Expressionist artists started with the minimum, the truth is that they incorporated complex layers of cultural allusion into their art. In a real sense Newman, Rothko and Still were History Painters by inclination but Abstract painters by formal inheritance. That is why the work is remarkable, for the diversity of residual signs that are successfully bound into their art.”

LikeLike

Thank you for replying to my comment.I remember Robert Linsley http://newabstraction.net/ commented on an essay I wrote http://martinmugar.blogspot.com/2013/11/spiraling-downward-from-minimal-to.html with these words:

“I like the way you connect the battle of ideas and the layering of forms – your notion of the “oppressed” forms showing at the back of the picture.”

This is in regards to the painting of Al Held but I think applies to Rothko.Not oppressed in his case but covered over.There is the numinous glow of the colors but they float in a sea of darkness. All that is part of the expressive strength of the work.It points to what is left out or can’t be expressed. I guess my anxiety in front of Rothko’s work might better be expressed as a dread of the unknown.The lived sunlit reality and then nothingness. “Whereof one cannot speak,thereof one must remain silent.” Bringing up Newman reminded me of an artist friend referring to how the vertical lines in his work had to be experienced bodily in a gallery.It was a visceral experience.

Elsewhere, I have referred to the need in some artists, the late Held and Stella for example to squeeze all they know about the world through complexity into one painting and how they failed in a rather dramatic way. Maybe is best to let the painting point outside of itself to something it cannot contain.

As for Kelly and Stella I agree with what you wrote: there is always the misreading as a way of getting out from under the shadow of their antecedents. They destroy painting itself in their ambition to do so.

LikeLike

Well Ill have a punt as Ive missed abcrit for a while.Personally I like many of the commentators,even if I differ hugely with their perceptions.Im sad to hear Jb wont be enjoying the Ab Ex show.Its very important to retain ones innocence.Im really looking forward to it,and like Hoyland ,feel a kinship with the best of them ,Pollock and Rothko.Yesterday I repainted a fairly large 7ft by 10ft Brancaster failure from last year.Before I started I got out my monographs on Frankenthaler and Louis to give me Dutch courage.Through all the stooping and bending,my back gave out halfway through and I found all the thrashing about exhausting .I retreated and returning the next day ,was initially pleased with the result,creating light as in the natural world .By lunchtime Id gone off the work ,for exactly the reasons Alan mentioned-Id seen it before ,probably painted the same format in the 70s!Was it worth doing ,oh YES.Its what being a painter is,working everyday God sends,trying to improve ,create something new,allow passage of feeling to come through the medium.Sometimes I get fed up with the whole Ab crit /Brancaster experience for one simple reason .I dont beleive I know how to make Art,which to me contains some poetry ,some feeling.Its just not enough to assume because we are literate we can divert the course of Art History,or try to.Making Art,whatever that is ,for me ,is something that happens despite my beliefs,its an act of Grace,like a saxaphone solo,very occasional beauty and Truth.All I can do ,like the Abstract expressionists,is go in everyday and try again.The worse thing I can do is just create another OBJECT in the physical world,full of my prejudices,however elegant. .Fortuneatly every now and again ,something happens.Thats Painting.

LikeLike

Did you see the Imagine programme the other week with writer Meg Roscoff?

She questioned, where does the unique artistic voice come from. For her it was a connection to the ‘powerful’ unconscious. She put forward her case: Although some feel there are horrible things lurking in the unconscious, like anxiety and death, it is also where love, desire, creativity, imagination and dreams can be found. She claimed, without both the conscious and unconscious mind, you cannot make great art. There were interviews with actresses, a musician and writers. It is about risk, daring to go into the unknown and regardless of the art form, going into the ‘unspoken stuff’, you have to visit corners of yourself. It interviewed Susie Orbach, psychotherapist, who feels, within the arts there is a tremendous amount of learning and skill, that allows you to surrender and go within another part of yourself. What is inside your head, your unconscious, is the you of you; and what makes everyone unique. If there is no you of you, in your painting, poem or acting, then it is dead. That is where the magic comes from, in that it is spiritual, beyond your control. Lewis Hou a neuroscience researcher in Edinburgh, gave his take on the unconscious. When they scanned the brain of a musician, playing something he knew; and then improvising, the scans were significantly different, other parts of the brain were active. He talked about a part of the brain that develops through our teenage years, which controls right and wrong. To enter the unconscious, he feels, that part of the brain gets turned off, which allows a creative mind to go much deeper, in letting go of inhibitions and trusting in whatever comes flowing out. Meg Roscoff is an American writer based in London, which makes her comments clearer, as they understand the unconscious much more, even offer masters degrees under the heading Process Work.

LikeLike

Well said, Patrick. And shame on you John B. For heading up this piece with that nauseating Clarkism. Robin is sitting on a sequel to my article on Farewell to an Idea (on abcrit) titled False Moderacy or Immoderate Falsity, which ends with the remark — “Clark stands revealed as an ostentatious fraud”. Of which the lines you quote are a prime example. I thought You’ld have realised that by now. Perhaps Robin feels that two attacks on one of his favourite authors is one too many.

He is also sitting on two substantial articles of mine, on The Gypsy of Matisse, and Gauguin-Van Gogh – Matisse. Do they not fit in with his touted “more open agenda”?.

LikeLike

Take Samuel Barber’s Knoxville, Summer of 1915, as sung by its dedicatee Eleanor Steber, and recently by the wonderful Russell Thomas (on YouTube), a work that is so out with the progressivist/historicist canon that it is not even mentioned in Taruskin’s History of 20 century music (Vol. 4) ( as none of Barber’s music is) , despite the fact that it was envied and imitated by many followers in the American idiom he helped to found. Yet it is a work full of the finest feeling (call it nostalgia if you must) , expressed with limpid transparency in the plainest of tonal/pentatonic “language”, and speaking directly to anyone with ears that have remained uncluttered with all the cerebral compulsiveness which drives so much of the aspirational wanna-be avant-grade. Check it out again, for I’m sure you’ve heard it before! .

LikeLike

Try this guy, he’s the best singer around at the moment: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6VCpbMPhmWY

You see, I don’t mind your connoisseurship on music, but…

I’ve said it before. I’ll no doubt say it again. The big issue in abstract modernism (visual art, if we may return to it) as it has been practised up to now is the conflation, by varying degrees and by very many practitioners, of the feelings experienced by the artist when making the work, and the achievement (poetic or otherwise) embodied in the finished painting or sculpture. You are right, in a sense, Patrick, to get fed up with all this discussion and analysis, like Alan does, because of course it doesn’t of itself produce poetry and feeling. You are right too to admit to not knowing how to make art. But the yearning gets you nowhere in itself, and it’s too easy in modernism to justify the shallowness of one’s own achievement by “citing” the procedural precedents employed by artists like Rothko and Still. Alan’s Rothko’s quote, about painting’s expansion in the mind of the beholder, though it sounds sexy, is about as much use as a chocolate teapot.

One minute Alan praises Brancaster, the next he slates it. His opinion of Brancaster changes with his opinion of the work in question. He’s judge and jury, the great man of taste, never wrong. Or so one must hope, otherwise you fuck people up. And Patrick’s yearning for poetry and feeling is closely linked to Alan’s dismissive attitude to some of the Brancaster work, and his suggestion that some of it doesn’t bear examination, requiring only a cursory thumbs up or thumbs down. Both attitudes derive from a certain kind of insider taste and connoisseurship of an aggrandised recent art-history, inflated beyond measure. Such empathising with the early adopters of minimalised abstract art like Rothko can appear to justify one’s own work’s familiar banalities, and so pass them off as refinements of deep feeling and poetic sensibility, or as vehicles for that sensitivity. In the end, being overwhelmed in the tractor-beam of these Americans (they are the over-analysed ones, Alan!) proves a vicarious activity. You have to find your own way, Patrick, which may not appear as grandiose, but is truer. Paradoxically, it seems almost impossible at present to find your own way on your own, such is the amount of stuff standing in the way.

Mr. Williams has reminded us of more stuff: “Meg Roscoff is an American writer based in London, which makes her comments clearer, as they understand the unconscious much more, even offer masters degrees under the heading Process Work.” I bet they do, indeed.

LikeLike

I do despair with the attitude of some Brancasterites, especially how critical you are of everyone else who has gone before, many of whom added something positive to a painting or sculptural direction within abstract art; and achieving great success in doing so. The disregard also applies to those who do not hold their same narrow views. It is a cliquey group, who think their own work is something special within abstract art of today. It seems most are trying to offer an idea slightly different, then claiming monumental differences that have never been considered before. If only you painted or sculpted, rather than imposing new ways of thinking through dialogue; something worthwhile is more likely to be found. You will not find it, by wanting it to happen; it will find you, or more likely someone else. It seems conversation after conversation, Brancastrians strangle the life out of what they are trying to achieve; it is very much a scientific or theoretical approach. So obsessed with finding aspects to promote as unique, the basics and common sense are often lost along the way. Like the Emperor’s new clothes, if you can convince others through words that something new exists, there needs to be others who are in a position to point out the obvious. Well done Alan Gouk! How refreshing to hear sense from Alan Gouk, with his knowledge and experience; but also his authority. Often you reference Alan Gouk and encourage him to comment, yet when he does give an honest opinion it is often slammed by Mr Greenwood. I do question how productive the ABCRIT website is. Now every aspect, or even idea, is being made available. Nothing is new, no one can see the evolutionary steps, or monumental ones, as process can be accessed all of the time. When something new has been found, others will tell you; and it will have more meaning than the self-posturing statements within ABCRIT.

Recently, the group has started using video to record gatherings. Quality is so poor in sound and actually using a video camera. It would help if you had a tripod and microphone system; possibly someone capable of editing. Some do not have written transcripts, which would help.

My last post, I hoped would help Patrick Jones in offering another way of thinking. When he wrote; ‘I dont beleive I know how to make Art,which to me contains some poetry ,some feeling.’ I wanted to suggest an area to consider. Unfortunately, Mr Greenwood has to give his dismissive view of Americans understanding an area better than he does. ‘Mr. Williams has reminded us of more stuff: “Meg Roscoff is an American writer based in London, which makes her comments clearer, as they understand the unconscious much more, even offer masters degrees under the heading Process Work.” I bet they do, indeed.’

‘I bet they do, indeed.’ Yes at present they do, but I accept more and more in Britain are gaining an understanding. For those who are able to create paintings or sculpture directly, connecting with your unconscious is worth exploring. Mr Greenwood, I believe you employ a scientific or theoretical approach to create your sculptures. I cannot imagine you would recognise real artistic emotions.

Is there anything new to say within abstract painting, or sculpture? Not within ABCRIT!

Goodbye.

LikeLike

Hello, Keith Williams. You say, Good-bye. I say, Hello. Hello, hello. Just want to encourage you NOT to give up on Abcrit or Brancaster. Keep trying.

The websites are NOT entertainment, NOT for “everybody.” You have to “work”—put in time reading/watching—be ready to change your “thinking.” It’s been fun for me.

I just read this about “normal” websites: http://nymag.com/selectall/2016/08/the-video-revolution-in-media-is-already-here.html. What madness! How different Abcrit and Brancaster are!

LikeLike

Robin: you’re sitting on 3—three!!!—new pieces of Alan’s???

I’m reading a great book by a young woman named Maggie Nelson. Had never heard of her until somebody on Twitter mentioned her. The Art of Cruelty: A Reckoning. I’m only 100 pages into it, but so far it’s great—all about Not-Abstract content. And I just read a passage that made me think of you and Alan.

“I also think of the college freshman I once had in a poetry workshop who announced, after we read the poem “In Celebration of My Uterus” by Anne Sexton, that he’d rather die than read yet another poem about a woman’s uterus or period. Dear God, I thought, has something radically changed in high school education? Are the youth now inundated with such poems by the time they get to college? Or—more likely to my mind—was it that a handful of poems on the topic (or, more likely still, this single one) made him feel as though he’d had enough?”

I don’t mean to compare you, Robin, to a college freshman—or Alan’s writing to Anne Sexton’s. Just trying to make the point that your reservations about Alan’s writing are pretty fancy. Not everybody has known Alan as long as you have. Not everybody has read his writing. Some of us—certainly I am—maybe Maggie Nelson is—are kind of starving for his kind of writing.

Let me bring in Maggie again:

“In short, purporting to know in advance what difference a difference might make—or purporting to be sick and tired of it before it has elaborated itself—is one fast way of being rid of it. Often, to experience the dissonance—especially in art—one has to take the time, and leave open the divine possibility of being taken by surprise. When someone first told me, for example, about a 1992 piece by performance artist Nao Bustamente called “Indig/urrito,” in which Bustamente invites white men from the audience to join her on stage, get down on their knees in penance for 500 years of white-male oppression of indigenous peoples, and take an absolving bite out of the burrito she is wielding as a strap-on, I think I spouted off some lazy dismissal of the venture, citing a disinterest in collective guilt, identity politics, audience humiliation, and dominatrix chic.

“After watching a fifteen-minute performance of the piece (filmed at Theater Artaud in San Francisco, and available for viewing on the artist’s website), I realized I couldn’t have been more wrong. Largely due to Bustamente’s quick-witted humor and benevolently sarcastic persona, the piece transforms political cliché into absurdist theater, opening up space for comedy, unpredictability, titillation, and an unlikely camaraderie. The indictment made by the piece, if there is any, is multivalent: Bustamente begins by poking fun at a (nameless) arts organization that has offered to fund artists of color whose work “addresses the past 500 years of oppression of indigenous peoples,” and introduces her piece as a response. She then invites “any white man who would like to take the burden of the past 500 years of guilt” to report to the stage. After no one ascends, she moves on to invite “anyone with inner white men,” then “anyone who is hungry,” then “anyone who knows a white man who is hungry,” and so on. The concept of collective guilt—along with that of unswerving identity—receives all the complication id deserves, swiftly and hilariously.”

Again I’m not trying to compare you, Robin, with Maggie, etc. And while I think your reservations about Alan’s writing are fancy, I think they’re interesting too—just as I think Alan’s reservations about Brancaster are “fancy”/”interesting”/etc. Thing is: these reservations shouldn’t get in the way of publishing Alan’s great writing—or of “broadcasting” the great Brancasters.

Who knows how the Ab Ex show’s going to turn out? I expect the most important responses will appear at Abcrit. Maybe they already have. I don’t know of any other place that allows for Abcrit’s openness/complexity.

Here’s the last paragraph from Maggie’s book:

“Preserving the space for such responses has been one of the book’s primary aims. Of equal importance has been making space for paying close attention, for recognizing and articulating ambivalence, uncertainty, repulsion, and pleasure. I have intended no special claim for art or literature—that is, no grand theory of their value. But I have meant to express throughout a deep appreciation of them as my teachers. For, as Barthes suggests, insofar as certain third terms—however volatile or disturbing—baffle the oppressive forces of reduction, generality, and dogmatism, they deserve to be called sweetness.”

LikeLike

Jock, your statement “I don’t know of any other place that allows for Abcrit’s openness/complexity.” rather contrasts with Mr. William’s last ever comment. I would really like to know what Keith gets up to himself – is he an artist? Perhaps we’ll never know now. You can’t please everyone.

Of course you have to engage with both the conscious and unconscious when making art, but even Alan has said there is not much use in discussing it. T.J. Clark makes a right hash of it when he tries it on Cezanne. Putting emphasis on it is very counter-productive. What have you to say about my subconscious motivations, Mr. Williams? They are my business, not yours. My work is your business, or should be. You are free, like everyone else, to criticise or praise it on Brancaster.

Can I assure you I’m not ‘sitting’ on anything of Alan’s. And can I urge Alan to start his own website, where he would be able to publish anything he wants. I’m more than happy to publish the occasional essay from him, provided it bears some relation to abstract art. His essay on Matisse’s “Baroness Gourgaud” was excellent. I don’t have to agree with him on everything to be able to say that. That’s a large part of the point of Abcrit.

LikeLike

I’ve just been re-reading The Gypsy , and Gauguin etc. and have to say that if you think they have no relevance to abstract art it must be a very claustrophobic kind of abstraction you are interested in. There is a much bigger world out there. Why not print them and let your followers judge for themselves.

Here is a taster almost at random from the Gauguin piece. — ” Modern painting, which really does begin with Cezanne and Manet, shows us truths about vision, namely that we do not see the phenomena of the world rationally or according to mathematical formulae a la Piera Della Francesca (great though he is in his century). When we attempt to focus on an object, or one aspect of the visual field, the rest slips and slides away from focus, subliminal presences, ghosts of perception, and bringing a whole picture together on a flat surface necessarily involves a hierarchy of perspectives fighting for prominence, adjusted to one another, blurred, cursory, tentative, (and so photography lies). Brushwork is spatial, but space is irrational. Any art in which theory precedes practice is a falsification of vision. When we are immersed in appreciation of the work of a great painter and turn to see the quotidian world, everything is mediated by that artist’s irrational vision “… Etc……

LikeLike

If you want to talk about Brancaster stuff do it on the Chronicles site. Can’t Gouk and Greenwood sort it out somewhere else? It was sort of interesting for a short time. Its just getting silly now.

I will say this here though. I’m sure every participant has their own reasons for taking part in the Chronicles. They are not ‘Master Classes’. Art is full of cliques. Make no mistake about that! Its all very territorial. Talking openly about the work you make takes courage- its actually anti-clique because you are de-mystifying and pulling apart all the shared clichés on which so much discourse on art depends (contemporary and historical). The films are useful because you can see when you (and others) are struggling- when you are leaning on received ideas. To take criticism and make something good from it, is the point for me and the challenge.

Alan Gouk might be a living legend and some sort of authority to some, but the world is a big place- bigger than him. Abcrit should be bigger than him or Robin. I can quite happily say I don’t give a flying Duchampian urinal about what Alan Gouk or anyone else thinks about the Brancaster Chronicles. They are what they are. Its a bit high minded and patronising to think that I take every word uttered by the other participants to the core of my being. I listen, yes. But I always come back to my own impressions, intuition and knowledge. The engagement hones skills. That’s all.

If you want high end production values and no content littered with tedious clichés then stick to “Artsnight”.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Or this — ” Paraphrasing Gauguin’s published statements, his aesthetic (partially shared with Van Gogh, partly at loggerheads, and none of it in practice at this date), runs as follows :

Intuition over reason. Thought over sensation. The emotive effect of colours — ” emotion first, understanding later” . “Drawing derives from colour, and not vice versa”. “Art is an abstraction; derive this abstraction from nature while dreaming before it, and think more of the creation which will result than of nature”. — To Schuffeneker, August 1888. “Like music — it acts on the soul through the intermediary of the senses. Harmonious colours correspond to the harmonies of sounds”

“How little power a reasoned sensation is” — “An idea can be formulated, but not so the sensation of the heart. ” Notes Synthetiques c.a. 1888.

………..it anticipates so many of the convictions which would come to shape modern painting, and a great deal of Matisse’s Notes of a Painter, 1908, but none of it had been realised, or scarcely even hinted at in Gauguin’s own painting up till October 1888. (When he went to Arles).

Somewhat prescient, don’t you think.!? I can’t help thinking of Hilde’s paintings when I read this.

LikeLike

For the record: Alan suggests I’m holding back on TWO essays (not three, Jock), but the ‘Gipsy’ I rejected ages ago; and I’ve never seen the Gauguin one.

LikeLike

Your record’s great, Robin.

Two things about Alan:

He’s not a “legend” in New York. I’d never heard of him until I read your praise of his ‘80s writing in Abstract Critical. WHAT A GIFT!

There were three artist/writer/talker guys—very much like Alan, very different too—who spoke regularly at the Studio School during the ‘90s: Louis Finkelstein, Andrew Forge, and Sidney Geist. Unforgettable talks. And the work that went into the talks: unbelievable. I remember Sidney was trying to get a talk together when he was 90. He just didn’t have the strength to do it. He almost cried when Graham let him off the hook. Sadly most of those talks are forgotten now. It is so great to have at least some of Alan’s writing up at Abstract Critical and Abcrit.

And the guy who organized those talks, Graham Nickson, the dean of the Studio School. His reward for all the exhausting, “useless” work he put into organizing the talks: nothing but torment and abuse. Familiar?

LikeLike

It’s a pretty topsy turvy view of abstraction that features Basil Beattie? , Rauchenberg and Mary Heillman ? But excludes Gauguin, Van Gogh and Matisse, is it not? It makes no sense. And the Gauguin piece was sent to you in February 2016, from my wife’s computer. Check it out. I’ve sent it again now. No explanation of why The Gypsy of Matisse has no relevance for your readers. And I had no idea I was a legend in my own lunchtime.

Robin dragged me into this in a gratuitous act of provocation, and not for the first time. Why do I care, I keep asking myself? Why not let them stew in their own juices. Perhaps it’s because I feel I am in some way partly responsible. The old St Martins Forums, where the leading participants cut their eye-teeth, were more straight from the shoulder, a lot less encumbered with art-theoretical baggage, irreverent but not cruel, and a lot more fun. These Roundheads have turned it into a tedious talking shop. Of course there is some merit in everything; but it behoves speakers (into microphones) to be honest and not pussy-foot around with politeness dressed up in technical language.

The conceit that art “starts from scratch” with Brancaster, and Robin’s discovery that he was a world authority on painting and sculpture, obscures the obvious fact that there is so much back story to every mark on canvas and every weld and bolt. And to pretend otherwise is leading the participants up a garden path with rose tinted spectacles (literally in some cases) , and lulling them into a false sense of the currency of their efforts. Not so much ” the road less travelled”, — more up,a gum-tree without a paddle.

LikeLike

On The Gypsy you replied, “I may publish it later, just so’s I can disagree with what you say about Monet.” And on The Gauguin piece you said –” Bloody Hell! ( or some such) — why don’t you set up your own website”, back in February.

LikeLike

Why are we talking about two Alan Gouk articles that Robin may or may not have read, when we have John Bunker’s at hand? And in regard to Keith Williams’ question as to how productive Abcrit is, I would answer with a resounding VERY! What is not productive is quibbling about the forum itself and accusing people of bias and agendas. Everyone has an agenda, it’s not that upsetting. There was a period of several months either side of the last new year period when Abcrit reached new heights. Alan’s contribution was crucial in that, as arguments on a great range of topics carried through into the next, maintaining tremendous focus and humour the whole way through, even when heated. I learnt so much from Alan and Robin in that period of time. There is nothing better than Abcrit, and not just because the alternatives are so poor, but because Abcrit and abstract critical are so bloody good, and we’re all hooked on it.

Trying to bring the focus back to John’s essay now, I would say that I fluctuate a bit in how I feel towards this period of painting. There is that part of you that respects the achievements that set up so much of what we do now. There is the part that just simply likes what you see, and there is the part that feels unmoved at times. I feel uneasy about having to accept certain works for what they are simply because it was a stepping stone towards something else. Isn’t everything? I don’t feel like going in to bat for Cubism, even though that arguably gave us everything. Despite my admiration for Braque and Picasso, Cubism looks to me like a neat and clever yet inadvertent downgrading of painting and a misreading of what Cézanne achieved. Of course, when I say that, I immediately worry that I’m being a reactionary, no different to all the “rear-guard” artists and conservative critics who have always been there along the way. But can a lack of enthusiasm for Rothko really just be put down to not being a sensitive enough viewer? Doesn’t that award him some kind of unimpeachable status? It’s really hard, this art thing. Having voices like those on Abcrit and Brancaster is so important. You just cannot do it alone, or at least I can’t.

A question for John, what specifically would you say is successful about Richter’s history painting? Because all the ones I’ve seen simply fell in a ditch on a visual level, and the conceptual element puts him on shaky ground. Is it important to reinvigorate sub-genres?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Based on my limited time at the Richter retrospective at Tate Modern, it became quite clear to me that the ‘October’ paintings seemed to hit head on Richter’s Doubt/Belief dichotomy in a much more ambitious way. It had a social/historical and art historical dynamic to it. He had found a way to dig at a repressed social reality through photography and get some kind of meaning back into the paintings. Much of the other work including his abstracts felt flaccid and/or insipid in comparison. That hunch interested me. That got me thinking about Ab Ex as a kind of abstract art that felt active, haptic and dynamic. It also was about digging at repressed social realities. If we see modern art as Meyer Schapiro did during the period in which Newman, Rothko and Pollock lay down the gauntlet to America’s cultural establishment and the international art world at large, then there is still the belief that we are all potentially active participants in the ever evolving definitions of art and society, not simply passive consumers of the next novelty turn or spectacle. The argument between visual ‘complexity’ and ‘economy’ from Schapiro’s perspective, becomes more of a dialogue to be shared and extended. I see history as a socially negotiable and perpetually contested realm. Future art will always be born of the ferment of these ongoing dialogues- otherwise it becomes insular, parasitic and irrelevant.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I found many Richter abstracts to feel almost like parodies of an abstract painting. But I can’t say that I get much meaning from the “October” works either, though would probably have to spend more time with them. Doubt and belief are very necessary ingredients for any painter. I think it pervades much of the AbEx work. Some of them must have felt quite fraudulent at times, as they carried their ideas through to their extreme, often very Minimal ends. They wouldn’t have had much of a critical framework with which to judge their efforts by, and that anxiety must have influenced the trajectory of the work. Perhaps that is what pushed many to make sure of themselves by developing and sticking to a signature style that would provide some sort of safety net.

LikeLike

As Noella says: very well put, Harry.

Important “big” point about doubt and Ab Ex: makes me think de Kooning never stuck with a “signature style”—doubt kept pushing him on.

But I just want to say something quickly about the “smaller” point you make about Richter. I hear/read you saying there’s not much difference between Richter’s “abstract” work and his “figurative” work. I agree. I see it all as kind of watered-down Warhol (John, I see Warhol as the guy who tried to get some kind of meaning back into painting through photography—I also see Warhol as the guy who “killed painting” (to quote de Kooning in a drunken outburst)), but I think the important point is not that Richter’s not the greatest painter in the world: the important “point” has to do with this “abstract” vs “figurative” business.

There is no real abstract dimension to Richter’s work: (that’s why it all sucks).

Often here and at Brancaster, somebody will notice something “figurative” in a work and condemn the work because of it. Often that somebody is making a useful point—but he or she is using the word “figurative” in a special way. Listening to Tony Smart in a Brancaster Chronicle the other day, I wanted to say: Picasso is abstract: Metzinger is figurative.

What I’m saying/trying to say is pretty crude. Patrick Heron is more subtle in “Cubism, Constructivism and the Architect.”

“One of the things that is present in varying degrees in, for instance (and I intend the utmost disparity within the categories that follow), Michelangelo, Picasso, Rembrandt, Cezanne, Poussin, Bonnard, Henry Moore, Constable, and Matthew Smith, but is absent in varying degrees from Pieter Breughel the Elder, Paul Klee, Durer, Blake, Memling, James Ensor, Turner, Sutherland, and Gauguin is a sense of complete identity of means and ends. With the first group, however varied their genius and unequal their greatness, the form is the apt and adequate vehicle for the poetry or other meaning. Everything that is expressed at all is expressed transmuted into color, rhythm, mass and “architecture”; the latter being composition, design, structure. No emotion is present which has not been thus dissolved in the pictorial medium. Form and content are one. But the painters in the second list have all strained the pictorial means in the attempt to achieve their ends—an attempt that is somehow too direct, too literal. . .”

It’s in this “spirit” that I see Matisse’s “The Gypsy” as abstract. (I’ve never seen the painting—only just found out about it thanks to Alan.) Maybe John/Robin think I’m just a dim-witted Formalist. Maybe I am, but, John/Robin, you’ve got to admit it’s kind of crazy/kind of “fauve” to think of “The Gypsy” as simply a dull formalist painting.

One more small thing, John. You MIGHT be amused by this tidbit of Studio School history. (Sorry to keep bringing in the Studio School, but it does amaze me: the things the school has in common with “Brancaster”—with “Scotland.”) Mercedes Matter is thought of as the founder of the school, its presiding “spirit” even now after her death around 2000. She hated art historians. She would only let two into the school: Leo Steinberg and Meyer Shapiro.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Very well put Harry.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I like your style, Harry. You have become an important aficionado too, and are out-brancastering Brancaster in some ways. So why don’t you write a proper article about your detailed reaction to specific paintings you saw in New York, if I may anticipate Robin as editor. Better still, come to England and review this show. Why am I bringing up these articles? Because I would like to see them printed, that’s why. And because John’s somewhat pointless ” anticipation” of this show just rehearses all the verbiage that surrounds the paintings and interjects prejudicial discourse between them and us. Glad you got something out of earlier exchanges. I’m not sure I did!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you Alan. I might just give it a shot. Coming to England is also very high on the agenda. From what I can tell, you have much better abstract art in your country than America does. Thanks again for all your contributions. I’d also like to see your articles printed.

LikeLike

Now there’s a thought Harry! We should arrange for you to do a Brancaster when you’re over here. You could invite Alan along so he can give you a very simple thumbs up or thumbs down. Or if he doesn’t want to come into the studio he could just do a happy face or a sad face through the window. No piffle paffle, political wiff waff or over intellectualising chit chat. Those were the days’ eh? D’où Venons Nous / Que Sommes Nous / Où Allons Nous. Happy face.

LikeLiked by 2 people

🙂

(perhaps we could do Brancaster with emoticons?)

LikeLiked by 1 person

LOL! And thank you for the offer, John. I wouldn’t knock it back.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Martin, I’m interested in what you say about the ‘anxiety’ you have with Rothko. It reminded me of an essay from the 70s by Lawrence Alloway concerning the “Residual Sign Systems in Abstract Expressionism”.

“…The term “gestural” is commonly applied to Abstract Expressionism with reference to conspicuous brushwork, but the term is also applicable to those of Newman’s paintings in which the whole work has a gestural function. The tall lines and man-sized area are a kind of gestural condensation……”

Although Alloway is talking about Newman here, I like the way he makes explicit the role of the ‘gestural’ and how it is absorbed into the painting surface by Newman and Rothko. Over the years I’ve spent a fair bit of time with the Rothkos at Tate. Not only in colour but in its application, the paint is creating tidal undertows- riptides and counter rhythms. For me they create in combination a very corporeal space full of slow and bloody undulations.

I think the best Ab Ex paintings somehow conflate a sense of interior or corporeal space with an exterior reality- the reality of the picture plane- in a very visceral and bodily way. Greenberg put like this…

“The best modern painting, though abstract, remains naturalistic to its core, despite all appearances to the contrary. It refers to the structure of the given world both outside and inside human beings.”

The Role of Nature in Modern Painting Partisan Review 1949. P 81

Like you Martin, I’m interested in what separates, say, Rothko and Newman from the likes of Ellsworth Kelly and Frank Stella. What is lost in translation between generations? And then, what is gained by ,sometimes, willed ‘mis-reading’?

Alloway goes on to say…

“Contrary to the notion therefore that the Abstract Expressionist artists started with the minimum, the truth is that they incorporated complex layers of cultural allusion into their art. In a real sense Newman, Rothko and Still were History Painters by inclination but Abstract painters by formal inheritance. That is why the work is remarkable, for the diversity of residual signs that are successfully bound into their art.”

LikeLike

John B, you have inadvertently gone some way to answer the question I started with, as to what is good about the Rothko. Your description is appealing: “a very corporeal space full of slow and bloody undulations.” but I can’t say I’ve ever experienced it. Does it apply to all Rothkos? I like it, but I find it’s vague and generalised.

“I think the best Ab Ex paintings somehow conflate a sense of interior or corporeal space with an exterior reality- the reality of the picture plane- in a very visceral and bodily way.”

By chance, and risking conflating the two sites again, I’ve just posted what amounts to a kind of combined rebuttal and agreement with this on Brancaster: https://branchron.com/2016/08/24/brancaster-chronicle-no-40-john-pollard-paintings/comment-page-1/#comment-395

LikeLiked by 1 person

Bruce Gagnier once visited Rothko’s studio, watched him paint for a while. Bruce was amazed by all the pigment Rothko had lying around: big boxes of cadmium red, etc. He’d never seen anything like it. Rothko would take the pigment, and rub it onto the rabbit-skin glue on his canvases.

Bruce has all kinds of love/respect for Rothko, but Bruce is not a color guy: he’s a drawing guy–and he asks, is there enough drawing in a Rothko to hold it together? Good question it seems to me. I don’t have an answer–but this drawing/color question seems to me to be important.

LikeLike

P.S. Can’t you see that if the truly awfully “bad” and not in the least abstract pictures of Basil Beattie are considered relevant to ABCRIT, but one of the pioneers of the very idea of abstraction, Gauguin, is not, there is something sadly amiss. But I don’t want to be a wet blanket and a drag on what is positive about this whole enterprise, as represented by Harry’s enthusiasm. So feel free to bar me from further participation. I think I’ve made my point, and there is no need to repeat it. If only others felt the same.

LikeLike

Bruce Gagnier, an artist (a great one), gave lunchtime art history lectures at the Studio School for many years. He introduced abstraction by talking about Gauguin and van Gogh.

LikeLike

“Bringing up Newman reminded me of an artist friend referring to how the vertical lines in his work had to be experienced bodily in a gallery. It was a visceral experience.”

Martin, can I suggest to your friend he tries hugging a lamppost.

LikeLike

Now is the time to say goodbyeeeee. Your left leg I like. It’s a lovely leg for the role. I’ve nothing against your left leg. The trouble is — neither have you!

LikeLiked by 1 person

LikeLiked by 1 person

Who’s the Dodo? I thought it was you, which is why I sent it to you. One last thing, and I really do mean last. — you’re spot on with that Heron Quote, Jock, and what a great quote it is. I didn’t notice it at first, what with the comments not being in the right chronological order. Compare it to that tosh from Lawrence Alloway. If you can’t see it, can’t sense it, can’t smell it, what makes you think it’s there. Maybe he was thinking of Motherwell’s Spanish Elegies, but to generalise from them — no, not on. Heron should have silenced John B. , but no fear. Back he comes with all that socio- political speculation. Darling Dodos!

LikeLike

I make that 43 very last things from the past year alone.

And Heron was wrong about Breughel.

Bye.

LikeLiked by 1 person

PPS. No 44. You’ve even started appropriating my jokes. It is indeed getting silly, sillier and sillier. And all the better for it. Such darling dodos!

LikeLike

Synergy or what? The Dodo skeleton shows a clear continuity from Smith’s Royal Bird to Tucker’s insights, to the From the Body episode (with skeletons) , to Robin’s latest steel and wood piece. Note the clear articulation and particularity of each element in both the Dodo and Yellow whatsit. A big step forward! Spooky?

LikeLike

1) Nobody knows what the fuck you’re talking about (nothing new there then) if they don’t follow Twitter. One day I’ll explain the internet to you. Bless.

2) It’s not all about you.

3) The dodo/Smith/Tucker/body comparison is bollocks. But that’s because you don’t yet get the three-dimensional imperative.

4) What happened to “steeliness”? (Or “woodiness”, for that matter?) Dropped, I hope.

5) What, no Christmas decorations? I’m disappointed.

6) That makes 45.

LikeLike

7) Try “sculpturaliness”

LikeLike

You know I was dismayed and sceptical when Tony Smart introduced the skeleton into the body projects way back in 1982? , but in the end it did help to concentrate focus on 3D articulation of a free-standing gravitationally conditioned structure. Smith’s Royal Bird and Jurassic Bird may be strung out in a line, but they serendipitously stirred the imagination for the future. The Dodo skeleton is three-dimensional if you care to look at it that way. Can’t you see the affinity with your new piece. Might as well put up a photo for your ABCRIT readers. We’ve strayed somewhat from the A.E.s and the Bunker piece, I’m glad to say.

LikeLike

P.S. Interesting that the sculptures are now being photographed for the Internet the moment they are finished, sort of. It’s called working for the internet’s approval. Scary! But enough of this tomfoolery. I’m off to play golf, for some time to come.

LikeLike

Modernist ease?

LikeLike

Since Smith is the Ab-Ex’s honorary sculptor, it’s not too far-fetched or ‘gatecrashing’ to talk about him here. Though they are amongst his better sculptures, ‘Royal Bird’ and ‘Jurassic Bird’ are flat, pictorial, figurative, almost pictographic, symbolic, and perhaps most fundamental of all, in terms of any comparison with what is happening now in new abstract sculpture (in Brancaster, of course – where else?), structured around symmetry/geometry.

As is the skeleton/body, which, as Alan suggests, are “gravitationally conditioned structure[s]”, though the Smiths avoid any such consideration by the use of concocted non-sculptural supports.

My new sculpture is, I trust, none of those things; certainly not flat/pictorial, and not even attempting to show a response to gravitational forces. My sculpture is free-moving in a fully three-dimensional, non-literal, non-geometric space of its own creation. I eschew all connection with the Gonzalez/Smith line of sculpture, which is (and for a long time has been) anathema to me. I absolutely hate semi-figurative “drawing in space”, especially when it’s NOT SPATIAL! There is a literal, historical connection to Smith, via Caro and welding, but not a sculptural connection of any validity. I am not a “steel sculptor”, as is now surely evident, even to you, Alan.

And there is a parallel here in supporting a largely uncritical stance to Ab-Ex painters, who are also often, if not always, flat, semi-figurative, symbolic or metaphorical, and structured around symmetry/geometry. Why I bang on about this, to the annoyance of part-time golfers the world over, is that it is really important to move on, move away from, get well clear of, comprehensively ditch, all the baggage that comes with the Ab-Exs and their followers (including, I might add, all John B’s political stuff), in order to progress and make good on the huge potential of both abstract painting and sculpture. We have to invent new stuff that’s got nothing to do with these guys.

Maybe Alan will never get this. It’s very worrying that he thinks this: https://pbs.twimg.com/media/Cq9ZfBeWYAAllxJ.jpg looks like a skeleton of a Dodo, or a figurative David Smith. I don’t see any connection at all. Alan is compelled to see a linear historcal link, even when it plainly does not exist.

LikeLike

Synergy is all—everything!

It is obvious that “Yellow Rattle,” Robin’s new sculpture, looks like a skeleton of a Dodo bird—so obvious that, understandably, Robin can’t see it. (Robin’s sculpture is terrific! It’s NOT about looking like a Dodo bird. It just does.)

I happened to have listened to this video of Michael Brenson talking about David Smith over the weekend. https://vimeo.com/41044183. It’s maybe “boring”—“just” biography, not much about sculpture—but how “exciting” are Robin’s “Victorian”—maybe simply “Freudian”—ideas about progress?

Robin talks about “a largely uncritical stance to Ab Ex painters.” I’m assuming he’s trying to say Alan’s stance is “largely uncritical.” But Alan lived through the ‘60s. He’s well aware of the very—maybe blindly—critical stance that just about everybody has taken toward Ab Ex painters and sculptors since, say, 1964 (the year the Studio School was founded). Alan does see things he values in Ab Ex painting and sculpture: he talks about them, keeps them “alive”—Studio School people did/do the same thing—so does Robin in his kind of crazy way.

I don’t think it’s far-fetched or “gate-crashing” to talk about David Smith or Robin’s new sculpture here. Robin does kind of flip out as he talks though. He becomes “political” in the way so many contemporary artists have. His “politics” might seem to be sophisticated—but they’re sophisticated “aesthetically,” not politically. (John Bunker’s “politics” are much more sophisticated “politically”—even though John’s “politics” are very tentative/shy.) I’m probably not being perfectly clear, but I think this might be the important thing about the Ab Ex show. How quick will we be to dismiss it all? How quickly will we say Cubism/Surrealism, the Smith/Gonzales line, been there/done that? I’m ADVANCED!!!

P.S. I also saw Mark Morris’s “Mozart Dances” over the weekend. Nice weekend! The Morris dance is even more ambitious than Robin’s sculpture. An evening long dance: 3 instrumental Mozart works: two concertos with a double piano sonata in the middle. It’s fun to think about Robin’s new sculpture and the Morris dance. Who’s in charge, the wood or the steel, the piano or the orchestra, the music or the dance? Is the whole dance just a stupid sop for rich old people? After all Mozart is dead, isn’t he?

LikeLike

Who gives a flying Duchampian urinal for Richter’s intentions and motivations? Let’s judge the paintings by the paintings. In the eighties Richter did some quite interesting highly-coloured abstract painting which challenged the norms of tastefulness in post-Greenbergian, post Ab-Ex, post-post-painterly abstract art. He did it largely by chucking into the mix some weird semi-figurative image-spaces. He couldn’t progress it, and turned to making the tedious banalities that are the squee-geed and “Cage”-type paintings. End of. I do think some of the eighties stuff is worth considering, but it’s for the most part very unresolved. He’s not really very good.

LikeLike

For me the ‘Cage’ series is not in the slightest sense abstract as the effects and imagery contained therein mimic comfortably (at least in my visual memory-bank) the distorted visual sensations produced by reflections of objects/lights etc. in moving or disturbed water. What I see tells me everything that I need to know about the abstract credentials of these paintings.For an abstract artist I’m not quite sure what it is about Richter that is ‘to beat’ for those who are of the ‘beating’ mind-set.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wow! I wasn’t expecting all that gush,–not! As that fine Muslim gent said to Donald Trump — Have you even read the American constitution? Have you even read my Letter from New York, or On T.J.Clark’s Farewell to an Idea. And have you even read my Gauguin-Van Gogh – Matisse.?.

LikeLike

I have read your T.J. Clark essay. I edited and proof-read it, and sorted the illustrations – remember? A shit job. It’s a terrific essay.

When you can find someone to edit your Van Gogh/Gauguin/Matisse thing down from 9068 to about 5000 words (from which it would greatly benefit) and proof-read it for typos and punctuation, then source the approx. 30-odd illustrations that you appear to need, and sort all their copyright issues… well, then I might re-consider publishing. It’s not terrific.

Maybe Jock would like to volunteer?

(P.S. Don’t bother with “The Gipsy”)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Happy to volunteer. Can’t start until October 16 though. I’ve “edited” talks by Louis Finkelstein. Alan’s William Shakespeare compared to Louis! And I’m sure you’re wrong about “The Gypsy”!

LikeLike

What was missed in all that was that I Was saying I like the new sculpture. Smiley face. Is that not enough to be going on with?.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Not really, no. Not if you think it’s a dodo. 😦

LikeLike

I wouldn’t change a word. That would ruin it. Maybe the odd suggested edit? You’re the Internet expert, and could easily do,it if you wanted. By the way, the repros for this piece of John’s are a weak lot, by and large, and what Richter is doing there anyway Is anyone’s guess. Try Olitski’s Greek Princess-8 , 1976 , my Wild Orchid 1978 , (Sam could supply), with this Richter, 2006. At least the former two come into Robert Storr’s category of the genuine attempt to paint an abstract picture. But yes, it’s not all about me. It’s all about John and you.

LikeLike

Alan, I guess I am arguing that your’s and Olitski’s abstract paintings are more ‘real’ than Richter’s. But why? And has this something to do with Clark’s “ludicrousness of lyric”?

LikeLike

Doubt and belief are a reality, of course, but to reduce this tension to a set of procedural or conceptual games (remember, ‘games’ can be very ‘serious’) with in the medium of painting is something else. Where abstract painting fits in to a post- Duchampian art world remains ,for me anyway, fraught. Maybe that’s why Richter tries to ‘take on’ abstract painting? And ‘intentions’ are all well and good but I think these works are the least convincing kind of paintings he has made. I find the 80s abstracts particularly slick and flaccid simulations. They remind me of an old text book explanation of abstraction that hinged on the prejudice that an abstract painting is just an exploded microcosm of a ‘proper’ representational painting. The proof of this was supposedly to reside, as I remember, in a very close up detail of the hand holding paint brushes and a palette from a Rembrandt self portrait being placed next to a full sized image of a de Kooning. It implied that an abstract painting’s meaning resided almost entirely on virtuoso paint handling and will always be secondary to and always refer back to representational painting. Richter’s planks of high keyed colour limply floating on blurry photo-like painterly residue is a sort of ‘sign’ for an ‘abstract painting’ -it is not the thing itself. It is lost in a hall of mirrors- endless representations of representations- mirrors of course, being an old favourite of Richter’s too.

As for Harry talking of a lack of a ‘critical framework’ for artists in the Ab Ex era? Well, that’s why I’m interested in Schapiro. There were critical frameworks as much as the myth of the individual alienated soul plagued by doubt and succumbing to the ills born of success and the ‘signature style’ still permeates our understanding of Ab Ex. There were other ways, and still are, to think about Ab Ex. As for Robin’s recent comment concerning leaving historical baggage behind and making stuff totally anew… Well, like Richter, the intentions are there but do the results add up? I can see the arguments and Robin continues to make them as clearly as he can. My aim though, is not simply to reiterate and reproduce what has gone before (or make excuses for it) but to try better to understand how and why it was made the way it was. Part of that process is about the shifting historical attitudes and social contexts that allow us to see artworks in particular ways. I try to do this in the hope of bringing in to sharper focus the limitations of my own understanding of what might be happening now and in the future to abstract art.

LikeLiked by 2 people