‘Nothing as drastic an innovation as abstract art could have come into existence save as a consequence of a most profound, relentless, unquenchable need. The need is for felt experience – intense, immediate, direct, subtle, unified, warm, vivid, rhythmic.’ Robert Motherwell, ‘What Abstract Art Means to Me’.

After the cramped hang and the waves of people flooding the RA show, this exhibition is an oasis. It includes a taste of all the facets of Motherwell’s work, from the earliest collage Pierrot’s Hat, 1943 and drawing Untitled 1944, it encompasses large canvasses and small works on paper up to his last collage Blue Guitar, 1991; it is a spacious hang in quiet place, filled with vibrant power.

Motherwell was the youngest of the so-called Abstract Expressionists and in some ways the outsider; and indeed still is – he was not honoured with a room of his own at the current RA survey, his name doesn’t appear on the publicity, and ‘Plato’s Cave’ was squashed into a corner, an error not mitigated by the fact that the massive ‘Elegy For The Spanish Republic No 126’ was given a whole wall.

Steeped in European sensibilities, philosophy and surrealism, Symbolist literature and psychoanalysis, he didn’t pursue a signature style, the trait so common in his contemporaries (and possibly the bane of their lives), and so is perhaps a little more tricky for historians and curators to place. He came at abstraction without the prolonged testing of figuration that all the rest of the boys were grounded in and for the most part managed to move on from (though DeKooning deliberately danced with it, and to a large extent Pollock never shook it off). He was European at heart, rooted in Matisse, Picasso and Miro as well as history painting such as Delacroix, on whose Journals he wrote his dissertation in Paris, Grenoble and Oxford. He often neglected this in order to paint. He was forever testing the ground and pushing his work and was an artist of versatility and breadth. He survived most of his contemporaries, though was by no means a hermit.

To be sure, Motherwell worked in series, and the Elegies, of which he made around two hundred (three variations of which are in this show), are probably the most iconic images of his oeuvre; but these punctuated his life along with the Opens and the big black Iberia paintings, as well as the hundreds of works on paper, including collages (where he wore his European influences on his sleeve; Gauloises packets, references to Eluard and Mallarme), series of paintings and drawings, and suites of prints (often connected with literature). And he had a particular palette of colours that were distinctive in their combinations; black and white, yellow ochre and soft blue, burnt umber and grey; however, these were often injected with a shot of red, orange or yellow and were far from the reputation for the ‘sombre palette and oppressive motifs’ (David Anfam in the RA’s Ab-Ex Gallery Guide 2016) that he is still saddled with.

The first room at Bernard Jacobson concentrates on smaller works on paper, showcasing the artist’s various printmaking skills in lithograph, etching and screen printing. Here is the characteristic predominance of black, the prime example being Black With No Way Out, 1983, a long format lithograph, which may be small in size but is huge in scale, its bulky black mass splattering out across the white ground and tinged with red at the top edge. It is by no means sombre. Elsewhere in the room the black is matched by red in Mexican Night II, 1984, and the uncharacteristic use of green with red in the Basque Suite, 1971. As Mattisse said, ‘Black is a force’, and Motherwell knew how to harness it to the full.

There is also early gouache and ink piece, Untitled from 1944, when he was still newly steeped in the surrealist practice of automatism, an approach learned from his close friendship with Matta with whom he spent time in Mexico in 1941 and of whom he said “In three months ….Matta gave me a ten-year education in Surrealism” – this was followed by time in Mexico City with Wolfgang Paalen, from whom “I got my postgraduate education in Surrealism, so to speak.” This baptism in surrealism alongside the soaking up of Mexican culture and colour (especially ochres and black) and a Mexican wife, laid the foundations for his life as an artist and was a constant thread, as seen in the exhibition. For example Mexican Window, 1974, and Mexican Night II, 1984, are a direct reference, but also the early gouache and ink drawing Untitled, 1944, owes a lot to Matta in its architectural space and biomorphic shapes in wet paint and ink that have been left to bleed and merge. This is one of a possible series in the same colours from that year including The Spanish Flying Machine and another Untitled.

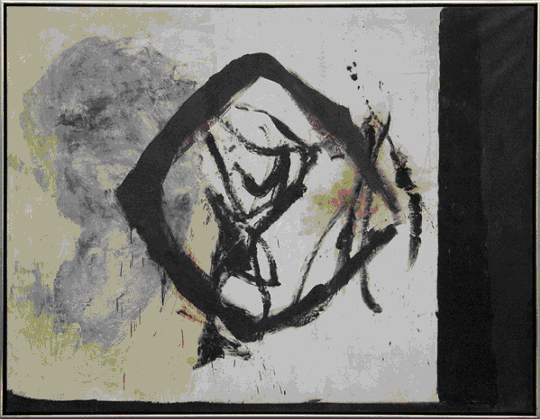

Greeting us at the door is a small Elegy on canvas, No 163, from 1979-82, which holds its scale at this reduced size. And for me is a much more powerful painting than its larger and earlier comrade downstairs. It is made of acrylic and conte crayon, the paint applied as a pink/orange overlay on the left hand side of the canvas, with the Elegy bars and oval roughly painted in black, then worked into with conte to give a contrasting surface; the conte marks fly off the main black to give a similar effect as dripped or splashed paint and emphasise the immediacy of the image and the mark making…. Except this was worked on in the space of two years, so some time passed between the initial work and the finishing touches. It seems that the final application was the pink over the black and the orange on the left.

Robert Motherwell, “Elegy for the Spanish Republic, No 163”, 1979-82, acrylic and conte crayon on canvas, 59.1 x 74.3cms.

The larger Elegy downstairs, No 130, 1974-5, though it dwarfs the former, is less powerful, less visceral and seems rather flat and tidy, holding its edges, and although the grey and blue-tinged vertical strips are worked, they still appear flat, as do the black bars and ovals….for me a disappointment, given the life of the smaller one and the impact of some others in the series. Even the flashes of colour in the top left, harking back to Elegy 34, 1953-4, do not save it. And it is not as if Motherwell didn’t know how to apply the acrylic in a more energised way. (see below)

In contrast, opposite it in the space, A View No 1. 1958, is a quietly energetic work in oil which creeps up on you, belying its apparent simplicity, and is loosely and freely painted. Slightly off centre to the left of the painting is a broken, linear square of roughly painted umber, rotated 45’ on a dirtied creamy off-white ground. A scumbled area of light blue/grey lies to the left beneath the shape, and there are some large scribbled marks in umber which are also ‘underneath’ the square, some of which are framed by it, but also escape free from its edges. The bottom of the canvas is edged with the same umber, while a wide vertical band of black holds the right hand edge. This band of black appears to be made up of two distinct qualities of the same colour, but the right hand one is dark umber and the left one is black. Was the black added last to make the rotated square appear less central? All of the various applications of the umber have different qualities, from thick and dense to thin and watery, adding to the felt experience of the painting. It is so much more alive than Elegy No 130. Motherwell said of this painting that “this work is probably my most purely Abstract Expressionist work of the period.” For me this painting is the star of the show.

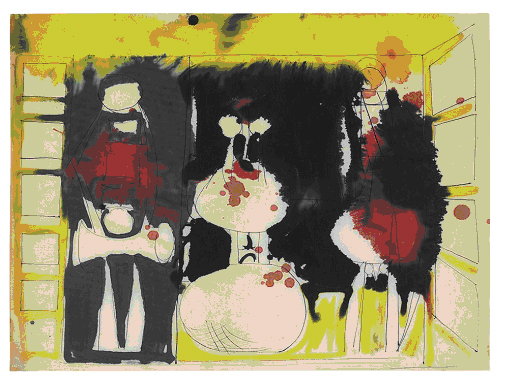

Completely different, but a close second is The Studio, 1987, an abundant painting of strong almost primary colours from thirty years later, and near the end of his life. It has echoes not only of Matisse and Picasso but also Miro. It hangs on the wall at the foot of the stairs, below the quirky, expansive space that towers up to the rooflights two stories up where the floors have been cut away. It is one of the most vibrant paintings he made, perhaps sitting alongside Je T’aime No 4, 1955-7. In fact it shares some of the characteristics of that painting in the colours and the combination of the two round shapes in the off-centre triangle…but ‘The Studio’ is much more punchy. This harks back to the energy and dynamism of his earlier automatism and ‘devil may care’ approach. The red pulls us back to Matisse’s Red Studio and the subject to Picasso’s The Studio – but the amorphous black shapes on the left hand side are redolent of Miro’s paintings and the old pull of surrealism. The black ovals in the blue triangle are resonant of the Elegies, as are the black verticals and horizontal below, suggesting a breaking-up and re-using of familiar forms in a new way. The vibrant red is overlayed with yellow and ochre, which also form the right hand slope of the blue triangle, which has been loosely painted so that the red shows through. The vertical passage of densely brushed orange defines the slope of the left hand side of the triangle. In typical Miro fashion, the black shapes on the left are edged with blue to make an optical punctuation. The whole thing is then finished off with charcoal lines contrasting with the roughly painted shapes and referring back to Picasso’s cubism.

Robert Motherwell, “The Studio”, 1987, acrylic and charcoal on canvas, 152.4 x 182.9 cms. Nick Moore’s own images

Opposite this, at the other end of the gallery, also with a wall to itself, is Mexican Window, 1974, one of the Open series. The large expanse of yellow ground is animated by vigorous, multidirectional brushstrokes of ochre, punctuated by the charcoal rectangle in the top half. In the playfulness of ambiguity, the suggested window becomes literally representational with the right hand shutter, loosely painted in black bars, thrown open against the wall; the vertical triangle on the left hand side suggests some depth of wall….but what strikes me is the way that it is a reversed version of Matisse’s Open Window, 1914, where the view through the window is black; here the strong yellow suggests a lit interior.

Interspersed amongst the large canvases are three small works in black, including untitled (Elegy), 1960, in tempera on board, which holds its own beside the larger version; on the other side of this is Frontier, oil on board from 1958. Two Figures, oil on board also from 1958, the least successful of this little series, is sandwiched between View No1 and California, the latter being another large painting on canvas from 1959. This is a loosely painted piece in his signature ochre and blue which could be a detail of a larger painting, with the large areas of colour expanding off the rectangle top and bottom; it also echoes the forms of the Wall Painting series from the early 50s, or the Elegies, but with the oval hollowed out into a blue line. It has a sprung tension set up by the bowed ochre shape and the cranked blue line that is held by the vertical charcoal line and the orange one to the right that brings it alive.

Another example of the breadth of Motherwell’s work is Beside the Sea No 3, oil on laminated rag paper, from a series made in1962. The series had a simple format, which gave him immense freedom to explore spontaneous mark making inspired by the sprays of water dashing over the sea wall at his studio/house in Provincetown. It was his first intensive use of oil on paper, using buckets of thinned oil paint, with the oil spreading and creating a halo effect around the colours. He had to use laminated rag paper because such was the force with which the mark was made, ‘at arms stretch, with brushes fixed on yard long handles’, that other paper he tried split open. A horizontal stroke was made about a third of the way up the paper, the ‘spray’ was then administered and another horizontal band of thinner blue was added below the original band. Again he plays with the ambiguity of abstraction/representation with the blue band possibly representing the sea, but then the ‘splash’ is in the darker colour. He made about forty works in this series and it paved the way for the possibilities of paint on paper that continued through his life, particularly with the Lyric Suite in 1965 and the Samurai series in 1974.

To complete the selection of his works, there is the small Grey Open from 1980, acrylic with charcoal lines on canvas board. In fact this succinct but wide ranging exhibition gives us a good feel of the man who might himself be described as intense, immediate, direct, subtle, unified, warm, vivid, and rhythmic… a giant of a man who made a substantial contribution to abstract painting in particular and painting in general, and deserves a much higher profile than he has been afforded so far. He was a man whose paintings lived and breathed as he did, and as Norbert Lynton said of him, ‘he wanted an art fully related to life as lived’.

Joyce wrote in Ulysses: “The supreme question of the work of art is; out of how deep a life does it spring?” – very deep indeed in Motherwell’s case; a major retrospective is long overdue here… was the last one really 1978 at the RA? What a shame we missed out on the 1997 show from Barcelona and Madrid curated by Dore Ashton, but apparently offers were turned down.

This exhibition is on at Bernard Jacobson until 26 November; don’t miss it, especially if you are going to the RA to see the ‘big boys’ play.

Nice piece, but surely the reproduction of The Studio is from a print, not from the painting, which is much tighter and studied than this, like the painting of a collage, rather than a collage. Once again, beware of judging anything from back-lit images on the screen, which falsifies and often enhances.

LikeLike

Just changed that image, which had indeed gone a bit weird.

BTW, it seems to me you quite often comment on work you have seen only on your Ipad or whatever, so I’m not sure you should be quite so preachy about this. I think we are mostly aware of the difficulties.

LikeLike

Why was I so underwhelmed with this show? Too much variety for a relatively small display?

LikeLike

Well, the revised image is still very far from the painting. It is much brighter and more soft focus than the original. Once photo-shopping enters the equasion, we are on a very slippery slope.

LikeLike

I had problems with this show,despite Jacobsons marvellous new space.Motherwells works are as complex as himself.They can appear dull and flat.Nobody mentioned the circle and triangle in California,scratched into the soft orange area,which almost could be a figure?I thought his last collage “Guitar” was riveting,and I kept going back to it.Im also not sure why Nick and John B .keep refering to the R.A.as some heavy hitting old boys network ,with aversion.Theres a huge amount to see in the R.A.show ,almost despite its hanging.Ill also say that Alans comments chime with my own reactions often and he is fairly much unparalled in his ability to talk like a painter looking .When that happens ,for me,Ab Crit becomes enormously exciting and valuable ,because we can discuss reactions to looking at Paintings and Sculpture as artists,not literary theory.Theres nothing like listening to a practioner ruminating as its the closest to the internal dialogue in the studio,where we spend untold hours not talking but thinking /feeling /muttering/cursing .

LikeLike

At Nick’s request, I’ve replaced “The Studio” image with two of his own photos.

LikeLike

God, but it’s so boring without any literary theory…

LikeLike

Personally, I think most of the work in this year’s Brancaster Chronicles was better than any of this.

#massivelyoverrated

LikeLike

…and if you over-revere this kind of minimal abstraction stuff, I can only see it being a restraint upon your own ambitions as an abstract artist.

LikeLike

Here’s a bit more literary theory – read this: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2016/nov/04/netflix-global-village-narcissists and tell me how Abcrit can get beyond preaching to the converted. This is a serious question. How do we engage with opposing views in the artworld, rather than just reinforcing out own position? I still don’t see much of a future for Abcrit unless we can open it up…

LikeLike

I still think that Abcrit would greatly benefit from a wider range of voices, as we had all hoped for a little while ago. I’m always introducing people to this site, and the responses I get are always very enthusiastic. But the chances of people actually contributing via comment or an article are pretty slim, and I’d be surprised if many became fully fledged devotees as regular commentators here certainly are.

Does this matter? Yes and no. It depends what we, and particularly Robin as editor, want this site to be for and about. Robin has suggested that he doesn’t want it to be a sort of weekend read. I don’t think it is, at least for the “converted”, because the comments and discussion that follow the article are often more rigorous and insightful than the articles. There are probably more moments from post-essay discussion that have stuck with me, than passages from the essays themselves.

But all this back and forth, however helpful it has been, perhaps does at some point become a kind of strange exercise, that has a kind of limit in just how much it gets us somewhere we haven’t already been. And we do need to get somewhere else. Surely that’s what this is all about. All this commenting, testing out your ideas against someone else’s. Why do it unless you want to extend yourself, give yourself a challenge, and grow (sorry if that sounds a bit corny).

I don’t know how you would go about “opening” up Abcrit. I assume this means reaching a wider audience, who have different views about art, and who hopefully would feel confident enough to express those views. We could make all kinds of suggestions, but would they work, and could they compromise the focus of the site? For instance, in the big wide world, art is not just abstract painting and sculpture. It takes in performance, video, installation, sound, as well as a lot of very good and very bad figurative art. Would abcrit be well served by trying to reach out to these other disciplines? And what would the motivation be? Surely not to dissuade them and win them over to abstract painting and sculpture.

I’ve suggested elsewhere that we could do well to think about post-modernity or contemporaneity and what abstract art’s place is in relation to all that. Not to assimilate, but to consider that huge challenges face us if we want abstract art to be of cultural significance and long-lasting consequence, similar to say Courbet. Can we assume that abstract art is still a part of this long tradition. Consider this even. Art is cultural, therefore it informs us of a particular culture and to some extent is particular to a culture. Even Cezanne the misanthrope informs us of France at a given period. So what is abstract art doing now, when it can be made in America or the UK, or where I am in Australia, or basically the world over? Perhaps this is indicative of the times we live in, globalised, homogenised. Or is it part of abstract art’s raison d’etre to completely transcend any visible link to a specific culture. This is in part why it is always being talked about in relation to “post-internet art”, which is of course just another attempt to attach it to a culture so as to package it up and “make sense” of it.

I think it is perhaps fanciful to think that at the end of the day, all things come out in the wash, and future generations will realise that abstract art got better and better through the decades following the 60s, and remains perhaps the most relevant and rewarding pursuit in visual art at this point in history. It won’t without branching out and entering a larger conversation, and perhaps could find things of value in other pursuits going on right now, not for the purposes of trying to literally incorporate elements of video or installation art into painting or sculpture, but just to broaden the mind and appreciate other people’s efforts in their own right. Then the favour might be returned as well.

I’ve come to agree that Abcrit needs to change, probably out of necessity. The site has integrity because it is actually prepared to question itself, or the editor and contributors are prepared to question its function. But also that integrity could slip if it continues on as some kind of chat room where you sort of already know what you’re going to get. I really hope it can continue on in some new form, because it is attempting to fill a huge gap in public discourse around abstract art, and more readers are finding out about it all the time, they just probably won’t comment because they’ve never heard of “Song For Chile”.

Something we could all do is suggest some ideas that could change Abcrit, and publicly dissect them, the way we already do all our ideas about abstract art. It’s Robin’s baby, but I can tell that a lot of contributors have much invested in it too. It would be good to have a forum that reflects us. That can change and grow in the same way that we tire of certain things and move on to something else. Maybe talking about AbEx all the time is getting a little tedious. Perhaps more talk about what’s being made right now would be a bit more energising and useful.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Harry, thank you for that really good set of thoughts, and I hope we might now hear from a few more people, spurred on by your example.

The very last point, about discussion of what is being made right now in progressive abstract art, is really better served by Brancaster Chronicles, where judgement and comments are based upon seeing the actual work, rather than reproductions on screen. The live talks work really well, and I think are very strong and important for those participating, but I can imagine they are difficult for outsiders to really get into via the films. What’s more, it then seems rather difficult to get a discussion going in the comments on the Brancaster site about particularities in the work, or even broader issues arising. Even the participants of Brancaster seem for the most part reluctant to extend the discussion online.

I take your point about most people not knowing about “Song for Chile” or other nuanced arguments of the ex-St. Martin’s contributors. That’s not a good direction for Abcrit either – and come to that, neither are the reminiscences about “Clem” etc.

I tend towards the idealistic notion that Abcrit should have a broader range of contributors, from across different points of view about new art, whose arguments would then be subject to scrutiny and criticism. But who will contibute to that forum? What’s in it for them?

More views please!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Some of us are not in a position to see the actual work discussed in Brancaster Chronicles, and thus our participation is limited to Abcrit. I personally appreciate the opportunity and don’t wish to lose it.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Perhaps invite artists to say something about their practice? Ideally avoiding the exhibition statement stuff about liminal space!

LikeLike

I once met him and engaged him in a conversation about heroism in art.He replied that the era of heroism was over and the artist should be a sociologist. Not sure what he meant exactly but this was in 1970 when pop art was dominant in the art scene and it is an art form that depends on a notion of the individual and its identity via mass culture, hence sociological. Maybe he wanted to be the last heroic artist and pull up the ladder behind him.

LikeLike

“I think Abstract Critical has provided an alternative forum for the voices of artists and art lovers who are tired of the banalities of the academic and market driven discourses that continue to alienate abstract art from the wider public and cultures.

A lot of time, effort and money has been spent creating this important space for debate and critique. I hope we can keep the spirit of AbCrit alive somehow. The heady mix of passionate opinions, frustration, anger interspersed with insightful wit and outright hilarity has been quite addictive! I have been on the wrong end of various stinging critiques myself (usually quite justified) and it has been an exhilarating way to find out what I really think. All the ups , downs and inherent problems of online debate only confirms the passionate commitment of the artists and writers who have contributed. This gives me great hope for the future. Although it will soon be in suspended animation- AbCrit ain’t over yet…….”

I wrote that in October 2014 in the comment section of the Abstract Critical announcement of its impending closure as an active site. It is now Nov 2016 and we have managed to keep it going as Abcrit. The reality is its up to contributors to keep the essays and reviews coming in and to comment as and when they can. I think it boils down to this… If you see a show you love or find difficult then review it. If you have particular ideas concerning art history, particular paintings or artists then write it and send it to Robin. I’m not sure it’s the job of Abcrit to constantly attempt to incite argument with an elite art world that is, on the whole, not interested in the level of discourse and insight that Abcrit is capable of. I think we should encourage and propagate an alternative space that is at once critical of established norms where the consumption of art is concerned, but more importantly, is positive about finding different ways to show abstract art and talk about it that does not rely upon kowtowing to galleries, institutions or art cliques.

I’m sure it would be difficult for most of us to constantly contribute to every debate as they unfold. But to have this space for argument and ideas is so important. I hope Robin can find the time and energy to keep it running and contributors, new and old, to keep the words and pictures rolling in.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Well put John, this site offers an amazing opportunity to learn and clarify thoughts and ideas. Perhaps some people who visit don’t feel confident enough to write a lengthy response, but I know many who thoroughly enjoy the discourse. I keep telling people about it, some just aren’t as obsessed as others I suppose. Maybe more individual material from artists currently working and exhibiting (so the work can be seen) could be good. Either that or expand Brancaster Chronicles to include more artists? Could B C offer a kind of service for artists in need of guidance or critical evaluation? Might be a bit of a tall order for Robin though.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Perhaps a rolling series of editors for Abcrit would help share the work load?

LikeLike

It is worth thinking of how to present thoughts and ideas on abstract art in new ways for abcrit. One idea is to ask artists to present a short piece on how they think their work has progressed, with examples. The following discussion might be really interesting in terms of what we value and how we judge work.

Most of the regular contributors to abcrit are, I assume, pretty robust individuals. While I wouldn’t want people to censor their thoughts there are better and worse ways of putting these across. I am aware that there are artists out there who may well want to contribute but the tone and possible come backs put them off.

I would miss abcrit so hope it can continue.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I know what you mean John P. I do feel pretty robust most of the time but I do feel a little nervous and apprehensive after I have posted something. I’m sure a few people feel like that too.

LikeLike

Thank you for all those thoughts… To answer in order:

Carl: Yes, I agree that Abcrit has to do something very different from Branchron, because of its very different circumstances, and it would be pointless to duplicate BC. I appreciate your unique voice on Abcrit, and your support.

Geoff: I have to resist the idea of artists making statements about their practice on Abcrit – because it’s not critical! And, more often than not, it’s indulgent, fogging up the very territory we want Abcrit to operate in – i.e. achievement rather than intention. That’s my line in the sand on Abcrit. There is not a lot of difference between the artist’s own statement and the gallery “puff” that John B correctly rails against.

That said, like anything else, I’m only against it until someone provides something really good along these lines. So if you want to try…

John B: Thanks, and I fully concur. And I’d like to stress the point – if I don’t get the material to publish, Abcrit dies a death.

John writes: “If you see a show you love or find difficult then review it. If you have particular ideas concerning art history, particular paintings or artists then write it and send it to Robin.” Yes, yes, yes; and to extend that idea, don’t be afraid to send just a paragraph. I’ll expand on this idea below.

Noela: Sorry, had to laugh – twice! Could we charge £1000 a pop for sorting someone’s work out with a crit! And why would it be an ESPECIALLY tall order for me?

You know, Brancaster is supposed to be a fully participatory thing, rather than a panel of experts declaiming on the work of some learner. Full participation is the best way to learn and progress. And one persons problem is someone else’s breakthrough.

Geoff again: Nice idea, but can’t get the essayists, never mind the editors. Anyway, Abcrit is MINE!

Shaun: Back again? Fine – write an essay about Tuyman’s work, if you like. Can’t guarantee publication, but we can’t do much with such terse comments, unless you expand. And you might be on the wrong site, since he’s not an abstract painter. Did I mention that Abcrit is about abstract art? But hey, make your case.

John P: Give it a try? It’s a little close to Geoff’s idea, but maybe. We can only try these things, and really I’m very open to trying anything, so long as we don’t end up with an artist’s “talking shop thingy”. Also, I’m very keen to get you contributing!

Noela: Sorry, laughed out loud again. You have no idea how nervous I feel when I take on Gouk. But nothing ventured, nothing gained. If you want to gain, then venture!

Here are a couple of ideas:

1. The first one I have touched upon when replying to John B. – don’t feel you have to WAIT to send me (privately) a comment or idea about something; and don’t feel you have to write A WHOLE ESSAY before you send me something. A paragraph or couple of sentences might suffice to start something off. Maybe I can cobble together a few such short contributions across a range of topics (or the same topic, even) and put them together as a post. Improvise! We don’t have to have THE BIG ESSAY (though happy to accept that too, unless it’s 9000 words that need editing).

2. I am minded to try ripping paragraphs or part-articles and pics from OTHER ARTBLOGS when they touch upon issues or viewpoints that I think are either interesting, damaging or controversial to the debate on past or advanced abstract art, so we can open up a discussion about them on Abcrit. Not sure how this will go down with other bloggers, but I see it as a way of getting a wider range of voices upon which we can all comment. I would hope too that other people can draw my attention to interesting material they see out there on the web.

Thanks, more thoughts welcome.

LikeLike

P.S. and apologies to Nick for dumping all this on the end of his fine essay.

LikeLike

No problem Robin, abcrit is a really good forum even though it gets bogged down in personal stuff sometimes. I have another piece on the way and it is far from minimal……all best

LikeLike

Happy to make you laugh Robin, I wasn’t thinking of a panel of experts, rather more of the same thing, maybe with different groupings. I know the experience is a fully participatory thing with the Brancaster Chronicles,I really like ‘one persons problem is someone else’s breakthrough ‘. The tall order would be organising such multiple sessions. Not a good idea maybe, I was just trying to think about involving more people. Not nervous now!

LikeLike

Likewise apologies to Nick.

LikeLike

I quite like the idea (mentioned above by John Bunker) of presenting/commenting single works.

I think this would open things up for a couple of reasons.

Firstly I’d guess that we’ve all been moved/ stimulated by single works, even where the “oeuvre” or the general approach of the artist leaves us cold. That would bring stuff onto abcrit from outside the bubble, but at the level of individual works, directly appreciated, without theoretical baggage.

Secondly, (echoing Robin) it is a lot less daunting to write a couple of strongly felt, subjective paragraphs on a single work than to attempt any kind of erudite summary of a show. Maybe more people would then be tempted to take part.

And thirdly, I imagine it as being more obviously subjective and maybe therefore less contentious/intimidating for contributors. It might be just as difficult as painting or making sculpture, but I think it could be a valuable experience to try to express (even just partially) what a particular artwork “does” for you in some form of words; and to hear what other works “do” for others as a possible opening for your own appreciation.

It would certainly involve commenting on reproductions, but it wouldn’t be about final judgements or meanings, just different ways of responding to what there is to see.

And it would still be the eyes and insights of abstract artists and others interested in abstract art, even if the subject matter strayed.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, have a go?

LikeLiked by 1 person