Cy Twombly Foundation Gifts 5 Sculptures to the Philadelphia Museum of Art

‘Timothy Rub, director and CEO of the museum, said, “Like the artist’s ‘Fifty Days at Iliam,’ this remarkable group of sculptures evokes the timeless themes sounded in Homer’s account of the Trojan War and offers a profound meditation on both classical history and the nature of modernity.” He added, “They represent an enormously important addition to our holdings of work by this great artist, who is a key figure in the history of contemporary art.”’

They obviously think very highly of Twombly at the Philadelphia Museum, as they seemingly do in museums all around the world, but as Carl Kandutsch recently asserted on Twitter, he is a vastly overrated artist. And how exactly, one might reasonably ask, do these dull sculptures evoke “the timeless themes sounded in Homer’s account of the Trojan War”? Is it a case similar to the politically wishfull thinking behind Motherwell’s Elegies, only with far worse work?

More here: https://www.artforum.com/news/id=64547

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..

The Art Newspaper reports on an exhibition of American and Belgian painting, on only until 16th November, at Vanderborght and Cinéma Galeries/the Underground in Brussels, which is curated by Barbara Rose. Quoting from her essay: ‘Minimal reductiveness can now be seen for what it is: a transitional step in the history of art, one necessary in order for painting to gain new freedom in favour of the play of the imagination. This new kind of pictorial space is allusive and not literal. The picture plane is recognizably flat, but on it, or in it, float any number of individual visions of a space that is neither that of the academic illusionism of the past, nor that of painting as a strictly literal object. New interpretations of texture and space, with their connotations of both tactility and metaphor, obviously vary from artist to artist.’

So what’s new about “allusive”? Looks like “academic illusionism” to me (writes Ms. Ellen). There has been an interesting exchange on Twitter, again involving Carl K., debating the merits or otherwise of Larry Poons. Might be worth continuing here on Abcrit… and comments on the rest of the work in this show would be interesting.

Rose’s essay here: http://theartnewspaper.com/comment/reviews/exhibitions/many-strategies-for-survival-barbara-rose-on-painting-after-postmodernism/

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..

In anticipation of the Tate’s big Rauschenberg show starting 1st December, Blouin Art reports on Robert Rauschenberg at Salvage at Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac in Paris:

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..

UAL provides a report on the symposium at Camberwell, Imperfect Reverse, which involved Natalie Dower, Katrina Blannin and Charley Peters (amongst others) in a discussion on human values and their relationship to systems art:

http://blogs.arts.ac.uk/pgcommunity/2016/11/04/imperfect-reverse-a-postgraduate-student-review/

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..

Sculptor Peter Hide, once of Stockwell Depot, now in Edmonton, Canada, has an exhibition (in Canada) and a new book.

A statement from the website reads:

Peter Hide is one of Alberta’s most important artists. His work has been described by the art critic Ben Street as the “mutability of form meet[ing] the permanence of matter; somewhere between the two is a moral truth about the demise of the body and the desire to sustain it.”

Pics here: http://www.scottgallery.com/artists/peter-hide

And book: https://www.amazon.ca/Peter-Hide-Sculptors-Life/dp/1926710401

So what is this thing about the body in Peter’s work, and how abstract is that? Another erstwhile Stockwell Depot sculptor, Katherine Gili, has a show in Ealing, London, which also has strongly figurative tendencies: http://media.wix.com/ugd/e32d86_1e5d13822a6f488594fd4d3f187911a8.pdf

Maybe Mr. Gouk could comment on this one…

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..

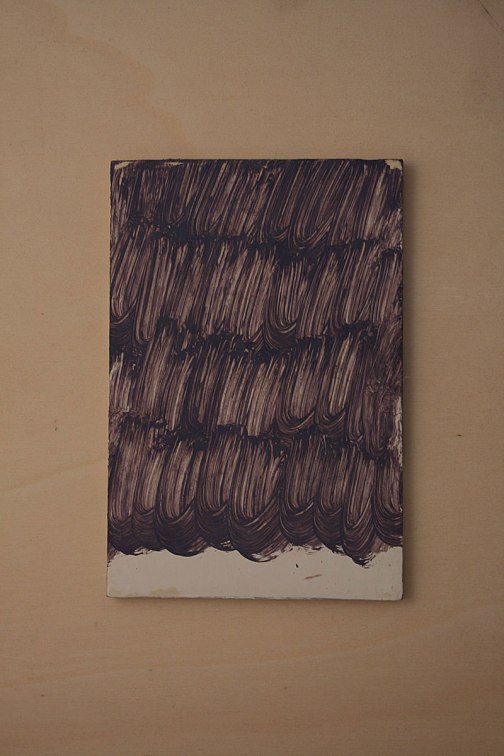

…and finally, Richard Ward writes a short commentary on a work by German painter Heribert Heindl:

‘Rows of thinly brushed, dark purple-brown ellipses on a creamy white ground.

Repetitive and regular enough to suggest some organising principle. Soft and uneven enough to exclude thoughts of a crystal or the graded perfection of a fish’s scales.

Perhaps the pattern on a tree’s bark? But these ellipses come to an end, abruptly, where the space runs out.

Something human then. Traces of another life. Like a little mosaic of shells on the beach or two stones balanced improbably on a rock.

An abstract and self-reflecting intelligence, delighting in pattern, aware of finitude.

And this, its record – concise and poignant like the outline of a hand, spat with red pigment onto a cave wall.’

Richard Ward.

Great to hear about the Peter Hide book—and the Katherine Gili show.

Very nice catalog online for the Gili show. Happy to see her drawings. They are NOT bad. They’re honest, intelligent—maybe too “intelligent”/brainy—and kind of naïve/uneducated at the same time. She seems to be clinging to some kind of idea about articulation that doesn’t allow her simply to put volumes in space—and an “idea” about drawing—an “idea” that seems to be shared by a lot of Abcritters, an “idea” I don’t understand—that drawing is all and only about literal representation: that’s not what drawing is for, say, de Kooning.

I saw Liz Gerring’s new dance “(T)here to (T)here” last week. I thought of Gili’s sculpture watching Gerring’s dance.

Alastair Macaulay says Gerring’s “mix of purity and athleticism is strong, clean, bold and exciting. It fluently combines modern technique with a postmodern and quasi-analytical scrutiny of pedestrians and athletes. But the mind that shapes the choreography is warmly modernist: scientific but also passionately and infectiously in love with movement.”

Apollinaire Scherr begins her review: “New Yorker Liz Gerring, aged 51, approaches choreography with an uncommon purity for her generation. As with her elders Trisha Brown and Merce Cunningham, neither story nor worldly reference intrudes on the parallel universe she creates from movement.

“And yet there are the dancers, who could not shrug off the drama of being human and in the world if they wanted to. The nearly hour-long “(T)here to (T)here” begins and ends with two of them, the former Cunningham trouper Brandon Collwes and Gerring stalwart Claire Westby, from whose distinct styles the dance’s lexicon seems to have emerged. Collwes offers a meticulous disassembly of the body into discrete moving parts, as well as a spacey detachment, despite the animal immediacy of abrupt starts and stops. The magnetic Westby’s joyous slashing of arms, buoyant leaps, swishy hips and coltish prances evince a childlike faith in movement as headlong freedom and fun.”

LikeLike

I’m going to say a few words about the Barbara Rose piece. There’s always something that irks me about assurances that painting is alive and well, and look, here are the painters who are doing it oh so well, responding to the manifold challenges of the digital age. It all sounds a little bit like… “Make Painting Great Again!”

And Rose’s evidences as to why these artists are making great paintings don’t seem to carry much weight. That they use texture? That they are spontaneous? That they want to expand the imagery of painting? That they do not see the plane as either a field of illusion or a literal object? These are all cliches that get thrown about quite a lot. They are so broad that they can be applied to just about any painting. Even with the post painterlies, thin stains of acrylic on raw cotton still leave a particular texture. I don’t necessarily disagree with these ideas or aims for a painting, but you have to be more specific.

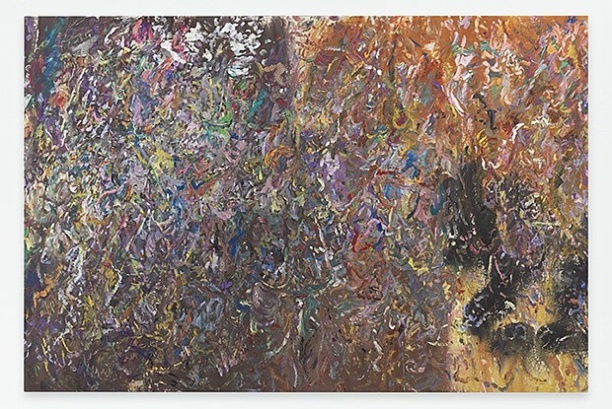

Of the three images provided, I found the Poons the most interesting. That said, I really did not think much of the Bannard and the Ghekiere, which looks like what I might have imagined the inside of a computer to look like when I was eight. But perhaps Carl and Robin would like to chip in here with some thoughts on Poons, for I am certainly no expert. I’m only somewhat familiar with three distinct phases of his work and it hasn’t ever been of much interest to me. The “mudslide” works seem very predetermined if that makes sense, and so perhaps “Cousin Durrell” felt more improvised. But the more you look at it the more repetitive and formulaic it seems to become. It just goes through the motions, this sort of curling patterning gesture recurring across the whole length of the work, the brown acting as a kind of backdrop, guaranteeing a sense of deeper and somewhat figurative space, particularly when it meets that brighter yellow section bottom right, which with that snaking black form, large by comparison to the plenitude of smaller marks, creates a shift in scale that supports the reading of a third dimension, though one that feels very familiar and for that reason reassuring.

The whole article and the exhibition it is about, seems to want to reassure us. Rose writes, “I have no idea whether in a hundred years their works will endure. This exhibition is a wager that they will.” Also, a lot of her apparent admiration for Poons seems to be very tied up in some idea that he stands in unique contrast to “Greenbergian dogma”, and this appears to be based on his refusal to participate in the show at LACMA, and on very thick paint application. I think we might need a little bit more to go on than that.

Other than that, I think Rose writes very openly and clearly, and I don’t want to scoff at her enthusiasm for these paintings and what she thinks they are achieving. I just happen to think that needing to justify the continuance of painting in the age of the digital has become one of those curatorial trappings.

On another note concerning Cy Twombly, I visited the Iliam galleries while at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Has there been a worse, more pretentious and more overrated artist than Cy Twombly. I mean, what the hell?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well, you’ve nailed “Cousin Durrell”. Despite being an attempt to make an all-inclusive, cover-all-the-bases, not-too-scarily-abstract, tip-your-hat-at-everything-but-especially-isn’t-impressionism-wonderful sort of painting, it is – and Poons remains, right from early doors – “repetitive and formulaic”. Always lessons to be learnt, though, aren’t there? Especially as we pick our way carefully towards a more abstract art. We know we don’t want to go THERE. From what I’ve seen of these recent Poons in the flesh (and Jacobson has shown them in London, as well as his older work occasionally), they are pretty weedy. They totally lack PRESSURE!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Just for the record, I liked and was influenced by Poons’ 1969-70 pictures, just before the “Elephant Skin” pictures (Fried’s coinage)– Polish Mix 1970 ( Museum of Fine Arts Boston) precisely because they were not formulaic, not dependent on “process”, and because though influenced by the gel wielding phase of Olitski, they were more painterly and improvisatory, slapdash and chancy. Poons can be seen in that 1971 film, Painters Painting tugging to release one from the floor of his very messy studio, where it had got stuck. He was only two years older than me, a new kid on the block. The Elephant skin pictures were more tidied up, with a lot of attention to cropping, avoiding “leaking” around the edges etc. They were shown at Kasmin’s gallery in March 1971. Howard Hodgkin said to me at the opening –” You don’t actually like these do you?” But I did, though not as much as the earlier ones.

Tony Caro brought Poons to my studio. I was painting on the stretcher, lifting the an as up to allow thin washes of fairly solid oil paint to run down in overlapping curtains , distantly related to Morris Louis. Poons got very excited, hopping around — ” there’s so much going on in them, maybe too much. I just love your blues and pinks,” Poons said. A month later my pictures were shown at the Museum of Modern Art, Oxford, where Michael Fried saw them, and again simultaneously at a Forum at St. Martins which Fried also attended. He said “they’re the best I’ve seen in London, but there’s too much simultaneous contrast in the colour. You must go to New York, where you’ll be forced to,become original. If you stay here you’ll be painting other people’s paintings for them.” Very ironic, in view of what happened.

When I first went to New York in April 1972, I met Poons again at a party in Clement Greenberg’s apartment in Central Park West. Poons gave a little start when he saw me. I wondered why, but found out soon after when I went to the opening of a show, curated by Kenworth Moffet at the Museum of Fine Arts Boston, a show of recent American Abstract colour painting, and there was Railroad Horse, just acquired by the museum, in which Poons was doing all the things, running thin paint vertically in overlapping curtains, that I had been doing in London, and on Fried’s advice had spent the rest of that year getting rid of in favour of a more harmonious and darker colour.. Fried was at the show. I tackled him about it, not knowing that he had written a very praising review of these new Poons pictures in Artforum. I said “he’s doing all the things I was doing last year.” ” Yes,” he said, “but his colour’s better”. And that’s all that seemed to matter.

Does any of this really matter now?. Poons got thoroughly stuck with what rapidly did become a formula, and by 1980 the “process” had degenerated into a thick solid wall of dull colour. Whereas , after a brief flirtation with the coal shovel pictures of 1978-79, which are not done by “process”, but adjusted and worked in the paint, Wild Orchid and In the Wake of the Plough for example, my style has developed in ways far beyond the all -over fixation which dogs so many American painters, following on from Pollock’s Lavender Mist, Eyes in the Heat, etc. but You’ld need to do a bit of research to find that out. So Poons is welcome to his little Pyrrhic victory.

LikeLiked by 1 person

P.S. Perhaps if you put up my recent Baltimore Oriole and Mandalaysian Orchid, and compared them with Poons’ recent efforts your readers would be able to judge for themselves their respective merits. Why is everyone going on about Poons in any case? Oh I see, it’s because some old has been of an American art critic is trying to create yet another false trail for painting in the technological age!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Regarding Cy Twombly.

A painting is a human utterance, as is a sculpture, a piece of music, a musical performance, a sentence, a gesture, a photograph, a wood carving, and so on.

To say that something is a human utterance is to say first that someone did made it, and that it makes sense. Making sense means having a point; an purported utterance that is pointless is also senseless, i.e., nonsense. Such is the difference between speaking and grunting, making noises. In other words, the meaning of an utterance is a matter of its being meant, and its being meant is a matter of it being worth saying. It follows that making sense involves accepting responsibility for meaning what one says and does. Modernism in the arts lays this condition bare; the convincingness of a modernist painting or sculpture depends on nothing more or less than the artist’s willingness to see it through, to take on the responsibility for meaning everything that is put into the work. (Post-modernism purports to be astonished at the fact that words in and of themselves, apart from being sensibly used by human beings, mean nothing – as if this were some sort of recent discovery rather than the meaning of King Lear’s tragedy in the play that William Shakespeare wrote in 1606 – concluding that this fact releases us from human responsibilities rather than forces them upon us.)

My objection to Twombly’s work is simple: I don’t see the point. I was introduced to his work by some academics who saw his scribble paintings as having something to do with Jacques Derrida’s theories about writing. Maybe they do, but that fact doesn’t alter my sense that Twombly’s work is pointless. A painting that illustrates a theory assumes that illustrating can take the place of expression, meaning for being meant. Timothy Rub’s evocation of “timeless themes sounded in Homer’s account of the Trojan War” provides an illustration of the way in which mock gravitus can be used to intimidate and stifle genuine attentiveness to the truth of one’s own experience.

So many themes and concepts are jammed into Barbara Rose’s essay that it’s hard to know if or where to intervene. Here are some quick observations.

The idea that photography threatened to or did kill off painting has become so entrenched as to acquire an aura of accepted historical fact. But it contains a huge assumption, namely, that one art with a medium unique and distinct to itself competes with an entirely different medium of expression. It would be more accurate to say that the invention of photography responded to the same crisis that result in modernist painting, namely the exhaustion of human attempts to recover the world by representing reality. (Abstraction would have become an aspiration for ambitious painting even if photography had never been invented.)

In the same paragraph Rose refers to “digital technology” which “appropriates, recombines, and recycles images in often surprising and novel visual combinations that create flashy, momentary, instantaneously consumed images that shock and awe.” I agree that something has happened in our culture that threatens the continued existence of painting and every other art; that this something is expressed in “digital technology”; and that its symptom is an apparent inability for anything to hold peoples’ attention, that not only have we all but lost the capacity for private experience (crucial to the continued viability of art as such) but the idea of privacy itself has become a commodity. But this phenomenon is not the result of photography and photography didn’t produce “digital technology.” By conflating the two, Rose betrays her academicism, her failure to put a finger on what it is she’s trying to discuss.

I feel that her essay sort of falls apart following the thumbnail history of modernism. Her discussion of Larry Poons, for example, is repetitive and not enlightening in that she fails over-emphasizes the importance of texture and relief and ignores Poons’ use of color. She therefore misses the way in which the tension between the literal and the abstract, which I believe lies at the heart of Poons’ efforts.

I feel that Rose’s academicism as displayed in this essay allows her a sense of optimism that I (while an outsider) don’t share.

LikeLiked by 1 person

One would only speculate, like Rose and many before her, that photography – or these days digital technology – might be in competition with painting if one confused the discipline of painting with the delivery of images. Photography and digital media get a large part of their meaning precisely from the fact that they ARE about delivery of an image – of something else in the world.

Painting, however, whilst being able to be projected in degraded form as an image by other media, gains the greater part of its meaning from the factors and values that make it far more than an image. These values start from the fact that all parts of a painting are made by a human hand, and continue all the way to asserting each individual painting’s quiddity as a real object that has its own, actual, specific place in the world. As we all know, and keep on repeating, seeing images of paintings, here or elsewhere, is a poor substitute for being in the presence of the real thing. Why? Because paintings are not images.

The irony about the work of Larry Poons and a number of his contemporaries, stuck at the arse-end of Greenbergian/Friedian conjecture as they were, and continuing in Poons case right up to his recent work, is that, unlike many artists, he and they absolutely did (and do) know the difference between painting and image, but their knowledge of that difference drove them down the path of attempting to find all of their content and all of their meaning in those processes (like sloshing paint about) and attributes (like flatness) that are unique to painting, in the belief that they would thus deliver all the content and all the meaning required of the discipline. Sadly (or perhaps gladly!), it’s not true.

LikeLike

To say that paintings like Railroad Horse or others of Poons’ work of the early 1970’s , or my Wild Orchid for instance are nothing more than “sloshing paint around” or about “flatness” is just plain blindness and obdurate denial. While Robin goes on finessing his hair splitting definitions of “spatial” and “depth”, he can’t see these very properties as they show themselves in the very paintings he traduces in this blanket dismissal. Poons’ paintings of the poured curtain period are actually quite varied in their spatial result. What seems to stick in Robin’s crop is that what space they have is created by colour, and not by thrusting shapes into recessional three dimensional illusion, as in representational painting. Meanwhile over on Brancaster the same issues that Poons and I faced 45 years ago are being revisited , as anyone who is committed to colour painting must.

LikeLike

Why don’t you do something useful and review the Katherine Gili show? You know you ought to. Might divert you from your favourite topic (you).

LikeLiked by 1 person

“Photography and digital media get a large part of their meaning precisely from the fact that they ARE about delivery of an image – of something else in the world.”

This sentence contains a misunderstanding of what a photograph is. The word “image” implies representation, one thing (the image) standing for another thing (“something else in the world”). Were that an accurate description of a photograph, then Barbara Rose and others would have a point because the photographic process could be said to provide a more accurate or complete image than paint on canvas. (This is basically the conventional wisdom: The invention of photography, by virtue of its superior capabilities relative to painting, forced painting to abandon representation.)

But a photograph does not provide an image of the thing; rather it provides the thing itself – but for the fact that it doesn’t exist. That’s why photography was never in competition with painting, which was driven to abstraction for reasons of its own.

“These values start from the fact that all parts of a painting are made by a human hand, and continue all the way to asserting each individual painting’s quiddity as a real object that has its own, actual, specific place in the world.”

I think this sentence also contains misunderstandings that are more difficult to describe. It’s true that the value of a painting exists by virtue of the fact that it is made by the human hand (i.e., it is what I called an “utterance” that must be meant in order not to be meaningless), but it is not true that a the value of a painting is based on its “quiddity as a real object” – unless you’re talking about buying and selling paintings, say, as an investment. The value of a painting (or any work of art) is rooted in its being different from other real objects (beds, chairs, skyscrapers, gold coins, etc.) and the difference is that other real objects are not meant in the way that paintings are (if they’re any good). Modernism happened in part because at some point in our history the difference between works of art and other things in the world collapsed for reasons that are obscure (at least to me), and it was at that point that painters sought to preserve the art of painting in the only way they could – by making abstract pictures.

“…but their [Poons’ and others’] knowledge of that difference drove them down the path of attempting to find all of their content and all of their meaning in those processes (like sloshing paint about) and attributes (like flatness) that are unique to painting, in the belief that they would thus deliver all the content and all the meaning required of the discipline.”

I don’t agree that Larry Poons pictures are about “process” any more than, say, Morris Louis’s pictures are. Nobody knows much about the processes used by Louis to make paintings and it doesn’t really matter. I believe that in modernism, the only thing that matters is the end result, regardless of the processes that produced it.

Finally, I think it’s about time Robin provided a real concrete example of “content” in an abstract painting or sculpture that doesn’t have to do with “attributes that are unique to painting.”

LikeLike

Should be fairly easy to provide an example of content in a sculpture that doesn’t have attributes that are unique to painting… (sorry). But seriously, it’s not that those attributes aren’t often in the mix. The modernist “narrowing down” of painting occurs when they are the only focus. If you want to see abstract content being talked around (it’s difficult to talk directly “about” it), just watch some Brancaster. Watch the tentative searching for human values over and above “process”, and in denial of flatness and other conceits.

Brancaster – which incidentally (Shaun) would quite happily continue without Abcrit, just doing what it’s doing, only better, year by year – does not, in my opinion, revisit very much of the stuff that happened in the sixties and seventies, and if it does occasionally touch down there, it’s off again with something new. For example, I don’t recall anything from back then touching upon anything like the careful and modulated balance between colour, tone, space, movement and light that is the hallmark (part of the content, even) of Hilde Skilton’s recent abstract work, and the focus of the discussion which attempted to get to grips with it.

And by the way, what would be the attributes and processes unique to sculpture?

LikeLike

In response to Robin and Carl. — yes indeed Impressionism is wonderful — suggested viewing this week — Monet’s Boulevard Des Capuchines, 1873, Pushkin Museum Moscow, Pissarro’s Cotes Des Boeufs National Gallery London, and Bonnard’s The Terrace 1918, Phillips Collection, Washington. I believe the air fares are favourable at the moment. And to Shaun — do your homework, do some research into my writing and painting before you start typing.

LikeLike

Should have gone to Specsavers! I’d suggest that Poons’ pictures –Needles 1972, Chrysler Museum of Art and Tantrum 2 1979, from the recent Barbara Rose exhibit in Belgium, are worth another look. This last one is the same proportions and almost exactly the same size as the pictures of mine he saw in 1971. There is no clogging up of the surface in these ones. But I’ll stick with the Pissarro.

LikeLike

Me too, but it’s amusing watching you squirm about Poons – kiss him or kill him?

How’s the Gili review coming on?

LikeLike

Shall we compare the great and wonderful Pissarro’s “Cotes Des Boeufs” with “Tantrum”?

LikeLike

Here’s a link to Tantrum 2 by Poons

http://pap.brussels/about-the-exhibition.html

LikeLike

Cotes des Boeufs: http://edge.shop.com/ccimg.shop.com/250000/254300/254300/products/lg_1389128253.jpg

LikeLike

I’ll be happy to review Kathy Gili’s show when I come to London in mid-December, but only if you put up Baltimore Oriole and Mandalaysian Orchid and compare with Cousin Durrell .

LikeLike

And how would I do that?

Tell you what: you review Kathy and I’ll personally review your forthcoming show at Hampstead School of Art in December (?) and post ever so many of your pics on Abcrit.

LikeLike

Haven’t you got the Dropbox images I sent you last week? And my show at HSOA is not until April.

LikeLike

Let’s wait till April then, got to see the real thing.

LikeLike

Shaun — I have tried to explain what I am looking for in painting so many times that I am blue in the face. And none of it will either justify my paintings or convince anyone of their worth. I don’t know what paintings of mine you have seen, or where you could have seen them. They are hard to locate at the best of times. I suspect you have taken umbrage at something I said in that video. Beginning by quoting Matisse does not in the least mean that I have nothing of my own to say or paint. And similarly because I am a fan of Hofmann does not mean that my paintings are derivative of Hofmann if you take a broad look at them over a span of years. He is only one of my influences. But enough about me. Since Robin seems determined not to let you see what I am doing, why I can only guess, I suggest looking on Facebook and Google. If you still think I am nothing but a follower of Hofmann there is nothing I can do for you. But please don’t use your difficulty with my writing as an excuse for rejecting the paintings. (Again I don’t know what writing you are thinking of ), but might I suggest a reading of Alan Davie – The Phenomenon of Expanding Form on Abstractcritical as an antidote to some of my perhaps more arduous pieces. By the way I do not write as an art historian, but as a painter engaged with the current problems in painting. Are you saying that a love of Cezanne, Monet, Matisse, Pollock etc is not of any help when trying to do something personal, and reaching for the depths that are within you, just as they did?

LikeLike

Hi Shaun, I have just been looking at some of your engaging, questioning comments on Tony Smart’s Brancaster Chronicle and was struck by your point that you felt there are two areas you find interesting when considering abstract art which are not covered by the Brancaster discussions. What are the areas you feel are not being addressed? And could they be applied to discussions on AbCrit ? Apologies if you have already stated your case and I have missed it.

LikeLike

I hope we can have a proper look at Alan’s work here on Abcrit in April. Meantime here are a couple of his new works:

For a shedload of recent Poons: http://www.danesecorey.com/exhibitions/larry-poons4?view=slider

LikeLike

I haven’t seen these (yet), so can’t comment, but hopefully Alan will stop moaning and get on with the Gili review.

LikeLike

This is from another website on Poons:

“the artist tacks a long roll of canvas twill to the wall…and begins to paint in scattered energetic bouts working near-feverishly along the unfurled roll. Inventing and finding coves of foci, massing strokes about freshly-made gestures or suddenly-discovered past ones, Poons instrumentalizes chance (the very hallmark of Abstract Expressionist painting) as he moves along the canvas causeway.”

Well, they all say that, don’t they. Sounds a bit like ebb and flow, surge and undertow…

Actually, the Poons remind me a lot of the way Gary Wragg paints… but that’s another story.

LikeLike

The reason why Poons’ pictures, Needles 1972 and Tantrum 2 1979 suggest an affinity with Impressionism, even if superficially, is not just because of their warm/cool high-keyed colour, but because their broad zones ( or “hedges”) are at one and the same time physically present (Fried’s presentness) but spatially operative and ambiguously located relative to one another. — that is how colour works if given room to do so. And the speckled, spattering detail adds to that outcome. Railroad Horse is perhaps the freshest and earliest of these pictures — fresh from my studio that is. I know, because I’ve actually seen it. It is about seven metres long by the way. If ever there were pictures that infringed the etiquette of the Greenbergian canon, it is these Poons’ of the early 70’s.

His elephant skin, or custard pie pictures of the year before were near monochromatic, (he seems to have suppressed them as none appear on the net) centralised puddles cropped to focus on the spread of what colour there was, agonising over where the picture ended, or “leaked”. So why he got excited at mine was because they showed a way to get beyond the all-over picture by breaking open the curtains and to allow stronger colour to hold larger zones. The phrase extrapolated from Matisse that seems to bug Shaun (from that video) is that colour needs surface area to operate at full strength. The more room is given to colour, and especially modelled colour, the more the surface of the picture is emphasised, while its spatial potential is enhanced. But it requires subtlety to bring off.

You can see these issues even as early as in the Pissarro Cote Des Boeufs, 1870’s and in Monet’s Boulevard Des Capuchines1873,. The elaboration of volumes, tree branches, bushes by tiny touches of coloured strokes creates incipient relief at odds with the homologous continuum of surface which the picture as whole is moving towards. Tree trunks stand out in relief against the spatial implication of the whole image. Pissarro later rejected divisionism for much the same reasons, plus the greying effect, in favour of a more full blooded acceptance of “depth” depiction and definite colour in the Late Boulevards. And so,on through to Matisse’s Fauvism.

The beauty of Fauvism is in its “utter directness” — the painter is allowed to make a clear statement –put the colour down and let it be , without elaboration or equivocation –let it make its mark without fuss or second thoughts. —Enter Heron’s Azalea Garden 1956 and on into abstraction. There are of course alternative voices. — Bonnard for instance. His “inspired timidity”, a counterweight to Matisse’s directness.

By the way, it is not critics, curators or collectors or the market who will decide the fate of paintings like these. It will be painters who will decide. The tragedy is that today’s Young painters have lost not only their moral compass but their aesthetic compass as well ( the art theory industry has them in thrall). They no longer know which way is up. No algorithm will ever produce anything as exciting as Pollock’s Lucifer 1947.

LikeLike

“The elaboration of volumes, tree branches, bushes by tiny touches of coloured strokes creates incipient relief at odds with the homologous continuum of surface which the picture as whole is moving towards.”

There’s a whole world in that “at odds”; that duality, if you like, that tension. And where does it go? Is it a world that is now lost to painting?

LikeLike

A question if I may Robin (indeed also to Carl and Alan).. You refer to the tension that Alan Gouk pinpoints in Pissaro’s Cotes des Boeufs. I’m wondering if you recognise any comparison (at least in principle if not quality of achievement) between the tension described in that particular Pissaro and the ‘tension between the literal and the abstract’ that Carl Kandutsch believes lies at the heart of larry Poons’ work. Has that Cotes des Boeufs’ tension possibly re-surfaced so to speak in Poons or any other abstract painters, prominent or otherwise

Between the literal and the abstract would seem to be an impossible but rather enticing place..

LikeLike

I’m going to answer this at the bottom so we can continue easier…

LikeLike

Early Gouks: https://pbs.twimg.com/media/CxYo1kDXUAAe0wa.jpg

Early Poons, “Mover” 1972: https://pbs.twimg.com/media/CxYo2-9WQAASVxM.jpg

This last is “Railroad Horse”, 1971

LikeLike

So how does Hoyland fit in to this? He was doing this kind of thing in 1970:

LikeLike

And this in 1971:

https://abcrit.files.wordpress.com/2015/10/john-hoyland_28-2-71-c2a9-the-john-hoyland-estate-photo-prudence-cuming-associates.jpg?w=598&h=349

LikeLike

Hoyland was in New York in the early seventies wasn’t he. Was that one really done in 1970.? But the fact remains that it was the visit to my studio that triggered the change in Poons’ methods from painting on the floor to up vertically. I know cos I was there. Mine are definitely 1970. Of course the official version of Poons’ change is attributed to Greenberg’s suggestion, obviously!

LikeLike

Hofmann says that Renoir understood the depth problem (which is a colour problem) to,a high degree by instinct. How much more is this true of Bonnard? . Take a look at his a – ma- zing La Palma, also in the Phillips Collection, Washington. Bonnard tends to be forgotten in all this cerebral stuff about abstraction etc..I wish had the air fare and the time. Maybe next year, send in the clowns!

LikeLike

Though not just a colour problem. There is also the tension question and the “pressure”. But enough from me. au Revoir.

LikeLike

Hermann Nitsch 1962

http://edit.nitschmuseum.at/nitschmuseum/de/veranstaltungen/8-deep-space-live-hermann-nitsch/brot-und-wein-150-x-150-1962-foto-manfred-thumberger/view

Is precedence so important? I would have thought it only starts to matter when the technique or process lacks “transparency” or “carrying power” for individual experience, making the resulting works barely distinguishable from artist to artist.

LikeLike

Wait till it happens to you.Then you’ll know whether it matters or not. I’ve already said it doesn’t matter in the long run because Poons got stuck with it. Don’t be so far fetched.

LikeLike

I don’t much like paintings with drips in, no matter how old or who did them first; and these days they’ve got much worse: http://www.waddingtoncustot.com/artists/28-ian-davenport/

(To be honest, I dislike that Bonnard “La Palma” too. Eek!)

LikeLike

Carl’s point on Twitter is interesting – that all of these poured paintings “are attempts to come to terms with the greatness of Louis’s Veils”.

Maybe, if the Veils are “great”. They were certainly thought of as great by lots of artists back then, and still are by many. I would maintain that these follow-on paintings are (also) mostly attempts to retreat into “process”, in an avoidance of having to discover or invent more interesting and engaging abstract content of a less literal kind. But then I would say that.

LikeLike

In my relatively uninformed amateurish opinion, Louis’s Veils (together with Pollock’s paintings of the late 1940s and early 50s) represent the height of accomplishment in 20th century American painting. My most powerful experiences with visual art have been in the presence of those overwhelming pictures (both those from 1954 and the later ones from ’58-59), and in fact seeing them was what led to my being interested in art in the first place. These pictures pretty much define what “abstract” means to me. I wish I had the courage to write about them.

Thank you for posting those very strong pictures by Gouk. I have never seen one in person. I have seen some paintings by Larry Poons, and without knowing much about the man, it seems to me as if the vertical orientation of the “thrown” or “poured” pictures represent a response to the “lightness” of Louis’s vertically oriented Veils, which weightlessness has to do with staining and the illusiveness of large expanses of color, especially when colors are layered AND stained as they are in the Veils. It looks like Poons was striving for a similar lateral expansiveness by way of color, but also countering that with physicality and weight, which is brought to bear by throwing paint at the tacked up canvas and letting gravity do the rest. That’s the tension – the illusiveness of color (which is not so much layered as in Louis as it is thrown together, often in a single strand of the cascading gooey pigment), and the physical implications and associations of weight and falling.

I think Louis’s decision to abandon the Veil format, without really exploring the options it opened up, and move on to different formats shows the kind of artist he was – deathly afraid of becoming mannered (like certain “Abstract Expressionist” painters), and totally committed to his life’s project, which was so sadly cut short.

Finally, I suspect (thinking about Pissarro) that Louis was probably very interested in Impressionism and it would be fascinating to try to understand how he used impressionist effects to make his pictures.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Terry,

That’s a really interesting question. I don’t think I know the answer as regards painting, and I doubt that I would agree with Carl about such a tension existing in Poons, because I think on the whole he feels like a pretty flaccid painter. Maybe Alan or another painter can say more on tension in painting, of whatever sort.

But I do think that exactly that tension exists for me in abstract sculpture, between the literal and the abstract, and I’m both for it and against it. There is a sort of literal-ish tension of metaphorical physicality, which I think certain semi-abstract sculptures might use, which might be more or less analogous to the body, but I can’t get along with that very happily. For me the tension in abstract sculpture lies somewhere in the spatiality of the work, rather than the physicality; in how the illusionistic space of the sculpture, as its pulled about and distorted by the non-structure or anti-structure of the sculpture (because I can’t any longer think of abstract sculpture as a material structure) resolves itself (or not) with the actual, literal space in which I and the viewer exist – and of course, in which it literally exists too. But that space, if you follow me, is NOT where it exists sculpturally.

I have to say too that this condition of tension is by no means something that abstract sculpture naturally falls into without a lot of effort and much failure. What it invariably wants to fall back into at every moment is the slack old literalness of objecthood.

But this is on the edge of my thinking. I don’t yet see – though I’d like to – how it can apply to abstract painting, and yet it appears to be a natural condition of good figurative painting, between spatial depth and surface, three-dimensionality and its resolution in two, which we have discussed before. There does seem to me to be a sort of similarity to how the tension might operate in both figurative painting and abstract sculpture, though that might be going too far, and a pointless analogy.

But quite where and how that duality and tension and its resolution is located in abstract painting continues to confound me, I have to admit. Maybe it is an issue really worth having out on Abcrit? Maybe it would help to think of examples of abstract paintings that people do think of as having some kind of tension from a resolved duality of some sort… Colour and shape don’t seem to have the makings of it, so it’s got to be more than that…?

Good question.

LikeLike

Thanks for this Robin. A lot to digest in your reply and I will try and come back on it. I certainly have been at that place that you describe as”the slack old literalness of objecthood’ in relation to making sculpture but perhaps still feel that some sense of what an abstract sculpture ultimately is will lie at least partly in our perception of what it imparts as an object above and beyond its physical ‘made’ qualities. To achieve sculpture that doesn’t have allusions to or suggestions of literal objects such as machinery and structures or the human figure and so on is of course where it gets tricky for the maker and also for anyone attempting to connect with it..

LikeLike

The only way you can do that is having the sculpture/anti-structure float in the air, because otherwise if it is free standing it will remain and have to come to terms with its physical, material structure, whether you like it or not. And viewers will sense that there’s something amiss otherwise. No wonder you’re in such a pickle. The dodo only has a stance because it is held up by hidden wires, otherwise it is just a pile of bones. Hidden wires, magic glue, bolts?. Get real. Sculptural,structure is not consonant with physical structure, but it has to convince on that level too, otherwise it is just a chimaera. Or a failed sculpture.

LikeLike

hence the tension…

LikeLike

There are two possibilities here. Either what I’ve written in my short response to Robin is just gobbledegook and I should be thanking you for your response for throwing some revelatory light onto my dark sea of unreal existence as some sort of item floating in an ocean of vinegar or you have misinterpreted what I have written with your conclusion that what I have said can only lead to some sort of ludicrous floating end-game for abstract sculpture. I completely agree with your view that free-standing sculpture has to come to terms with its physical, material structure but, with respect, that is so dazzlingly obvious that it’s almost not worth saying. As I said (and I accept that I didn’t fully expand this point) I believe that it is also important to understand that over and above but yes also, through those considerations sculpture has to achieve some sort of identity as an object (perhaps Robin’s content’ ?)’and not just be a concoction of material, physical stuff that succeeds only in the sense of fulfillingg pre-determined ‘literal’ criteria.

LikeLike

Sorry, I obviously got in a bit of a pickle there with fulfilling!-thinking of eggs probably.

LikeLike

“But I do think that exactly that tension exists for me in abstract sculpture, between the literal and the abstract, and I’m both for it and against it.”

As a general philosophical point, I think we need to be careful about the dichotomy “literal” vs. “abstract”.

In the so-called “age of science”, everything that exists exists literally, as an thing in the world. There is not another category of objects that exist in some other way (“abstractly”).

This phenomenological fact of modern experience produced the conditions out of which modernism was born (in painting, those conditions are called “realism” – Courbet leads to Manet).

In my understanding, modernism represented an aspiration to salvage a kind of human experience (once provided by religion) in which certain things in the world could be seen and valued other than as objects (of commerce, as scientific evidence, etc.). The abstract never really overcomes once and for all the literal, but the term does indicate a kind of experience that CAN happen with works of art. (The religious connotations of this logic are alluded to in Fried’s formulation, “Presentness is grace.”) But when it does occur, it is always in tension with the literal – hence the importance of the idea of “conviction” in the experience of modernist painting and sculpture. Even the best abstract works can suddenly (when conviction – or, from the artist’s viewpoint, inspiration, lapses) strike us as mere objects, no different from any other. In other words, the tension between literal and abstract is never really resolved, so it’s a matter of keeping faith (notwithstanding passing fashions like post-modernism, etc.).

LikeLike

Interesting that sculpture comes into this debate now.

This is what I think at the moment which may be relevant.

There seems to be a problem between something literal and something abstract. If one takes the view that abstract in its most talked about meaning is something to do with non-representational and more saw abstract as a condition to do with freedom for other conditions say space and three dimensionality etc. to work together and ultimately come together leave one looking around for the glue so to speak in a non-literal form.

Abstract requires that the new sculpture be non-literal non-representational and not in relying on outside forces to hold the experience together.So we are talking of a non-literal structure i.e. no cross referencing to the known structures of the world and I would suggest that I know that to exist already in the new sculpture of today. That would be illusion in that nothing that the sculpture does is actual or literal.

Further to this I would like to suggest that one could at least consider to start to think of the word abstract in two ways one being the standard hook of painting and sculpture which purports to be non-representational and another more interesting use of abstract when rid of the dependencies of representational art and brought into dialogue with physicality three dimensionality etc. a new role emerges of abstract as a force for building new experiences.

LikeLike

Thanks for the reply Shaun, I think it is very acceptable to discuss what is in front of everyone during a Brancaster Chronicle and to voice approval or not. I don’t feel abstract art is being ‘conquered into submission’ during the discussions , I wonder what made you feel that. The last point in Tony Smart’s post encapsulates the impetus for making abstract work, namely as a ‘force for building new experiences’. Would you find it more relevant if the physical process of working was explained in greater depth? It is really helpful when people react to what has been created and as Robin has said , sorry for repeating it again but, ‘one person’s problem is someone else’s solution’.

As for drippy paintings, there can be a real attraction , I do like the rich colour in the Hoyland especially, but it feels like a way of working than can perhaps be indulged for a while but then moved on from.

LikeLike

Just say that you cannot point to a post-modernist work that stands comparison with acknowledged masterpieces of modernism. Because therw aren’t any.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Just a question: can we bracket the labels ‘modernism’ and ‘post-modernism’ but keep the importance of history and cultural change? Perhaps, in a way, art works transcend these categories we attempt to place them in?

LikeLike

Well, context is relevant as our own philosophies, ideas, values, will influence what, how, we see: and this is Abcrit not Brancaster.

As far as I am aware there are many modernist views. I’m no expert but aren’t there ideas within modernism that challenge prevailing views, realities, etc? Isn’t there, in modernism, an element of what post-modernism is all about? So, it gets complicated to define and compartmentalise eras, works, theories, etc.

My interest is how issues of context might help how we make and judge art. Simple compartmentalising or categorising is not that helpful, although we all fall into it.

LikeLike

First you said you had never seen one of my paintings. Then you reeled off a list of other painters they reminded you of. Now you think I have something of the post-modernist in me. Let’s face it, the post-modern eye is as lazy as yours, and like you, has the attention span of a gnat. Too lazy to finish an article, too lazy to see what’s original in a painting. And you want a verbal précis of what I’m about. Descartes and Kant my arse. Frog off!

LikeLike

I’d be quite happy to be labelled a “post-modernist” were it not for then being associated with a pile of absolute crap art and architecture. Sam Cornish keeps telling me I’m a modernist whether I like it or not, and that I can’t do anything about it, world without end. Better do as John P. suggests; ditch the labels and talk about the work.

I’d quite like to get back to talking about the sculpture issue, because although we mostly talk about painting on Abcrit, I think abstract sculpture is a more interesting and possibly more enlightening topic (for me, at least).

The business of how a sculpture stands in the world, which Alan (quite rightly, in a way) takes me to task for, is something I think about a great deal, and Tony and I often discuss it privately, as well as directly tackling the subject often over the past few years on Brancaster. Despite me now suggesting that an abstract sculpture is not a material structure, I have over the years probably over-obsessed about sculpture’s relations with the floor. What I now propose (and I think it concurs to some extent with what Tony says?) is that, yes, of course you have to make sculpture stand up in the world without smoke and mirrors, it has to convince; but if you make that consideration the “raison d’être” or main content of the work, you will end up with something that is mainly concerned with its “configurational” aspects, i.e. a structure that is, in essence, some kind of figuration (in an association with something else in the world, albeit figure or object). The content of the work needs, in my opinion, to be about more, much more, than the proposition of how it stands. The latter needs to be dealt with, but I personally would prefer that it was dealt with “naturally” (which might need a lot of consideration), and not in any way privileged as content.

As a good example, Mark’s best work of the two sculptures he made for Brancaster this year was generally considered a great success by all, including Mark (and Alan too, online), and perhaps in contrast to his previous works, which focussed so much on how they held themselves up in the battle against gravity (engaging though that battle was), did not have much to say about how it stood, but was just naturally “up”. This is what Mark had to say on the Brancaster site back in August:

“The instability that Tony refers to is visual instability, not physical or structural instability. This is also linked to Anne’s comment about the lack of any obvious construction or support. In turn this is all summed up very succinctly by Robin’s phrase “predetermined functionality” or the lack of it in this case. For me, the crux of this talk is that abstraction can be freed up by getting rid of functionality in all of its manifestations, not just structural but also compositional, cause and effect, which Tony refers to as storyline at the end of the talk.”

I’d say the “tension” in this piece had nothing to do with configuration or material structure. I’d say it was Mark’s most abstract piece. And I’d agree with Tony that “abstract” is the key to sculptural freedom.

There is an analogy with modernist painting here, which I’ve partly made already; over-consideration of the essential properties of painting (flatness etc.) lead to a dead-end. So painting is flat – so what! What else is it too? And similarly, so abstract sculpture stands in the world – so what! What else does it do? Lots, I hope. Things we haven’t yet dreamt of, and that don’t yet exist.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It is annoying and confusing that the comments are coming up out of their correct time sequence. For instance my comment about “stance” was not a reply to Terry Ryall, as he seemed to take umbrage at, but to Robin. And to Shaun — it’s odd that you should use two Idealist/ rationalist/ Enlightenmentish philosophers to shore up the chic cynicism, slick technocracy and “parlour despair” (William J Curtis) of post-modernism’s nihilist trashing of all values. Descartes and Kant are a lot more subtle than your undergraduate gloss. Didn’t bother to finish them either, did you!

LikeLike

I did wonder, apologies for that Alan.

LikeLike

Robin perhaps it would be better to preserve the integrity of this thread (and ease some of my embarrassment!) if you erased my two replies (the rant and the typo apology) to Alan’s comment given that it was not in fact addressed to me.Aoolgies to you as well. I”ll just get my coat.

LikeLike

Hey, listen to her speech, this must be good for sculpture! http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/entertainment-arts-38014384

LikeLike

Yes , give David Medalla ten grand. He’s running out of Daz.

LikeLike

Yes, give him a retrospective. The world needs more foam. I remember being sent time and again to Signals gallery in 1964/65 from the British Council by its Director Lilian Somerville , because she couldn’t bear the man, to see the foam sculptures and all that kinetic art from Latin America, the stuff that Guy Brett used to champion. The Tate probably have a shed load of it somewhere. For some reason the young bloods out of Cambridge seemed to think it was cutting edge, the way so many now think of the technological flux. And then there was old Harald Szeemann’s “When Attitude becomes Form”. Medalla was probably in that for all I know. The British Council is a very different place now of course. Yes indeed . Give him a retrospective at the British Pavilion in Venice. Long standing service medal,to “conceptual art”.

LikeLike

“We should not be asserting a hierarchy in saying, this person is a winner above and beyond anybody else,” she told BBC Radio 5 live’s Colin Paterson.

“The context of the world’s political landscape is changing so drastically,” she went on.

“Amidst that, the art world has a responsibility to uphold an umbrella of egalitarianism and democracy and openness.”

The art world has a responsibility to follow changes in the political landscape, such as the draining of any and all integrity, meaning and hope from public discourse, election of reality TV stars to run the world, and so on. But of course, everyone’s a winner and even those who lose get a nice prize in the form of a pat on the back and some hollow talk about egalitarianism and openness and other bromides.

LikeLike

Harald Szeemann’s is the man credited with launching the idea of curatorship as an art form in its own right, with consequences we are still living with. Unfortunately artists seem only too willing to comply, and offer up on demand.

There’s the “post-truth” politics of Breitbart — the “post-medium specific” art of the curatorial consensus. It’s all linked. It’s all a wind up, (as Cathy Newman elicited on Channel 4 news) , all a tease to the serious minded. Only sheep fall for it. Don’t rise to it.

By the way, there is an amusing refutation, if refutation is needed, of the idea that time and space are subjective, in that little mix-up between Terry’s and my comments, he assuming that mine referred to an earlier one of his, when in fact his one actually appeared later. Unless that is we all exist in a parallel universe inside Robin’s head. Hard to think of a Shaun Collins emanating there. But enough of this tom-foolery. I’m off.

LikeLike

Blimey!! does that mean that I knew what you were going to write before you did??

LikeLike

The above is a reply to Alan’s comment timed at 11.58 am on the 19th.

LikeLike

When someone says that painting or sculpture “must” reflect the post-modern “reality” of our time, they are telling me that I MUST submit , MUST conform, to something that strikes me as unreal, that fills me with the nausea of disorientation in a world where NOTHING is true, where people like President Obama wins a Nobel Peace prize for public speaking, where countries are destroyed and millions of people are made into refugees in the name of “human rights” and “democracy” and “freedom”, where wisdom consists of the “appropriation” (i.e., recycling) of worn out slogans and clichés that have long since lost any meaning, where I am under a moral imperative to NOT resist the pervasiveness of compulsive consumption and commodification of experience, where meaning and significance is “always already” deferred and out of reach, where the difference between the authentic and the disingenuous is “undecidable”, where striving is pointless and hope and faith are considered naïve and outré. As all of these things become more pervasive, more universal, and harder to resist, art and seriousness become that much MORE important as perhaps the only way to maintain attentiveness to the value of my own experience in the limited number of days I have left on earth.

LikeLike

Poons v Gouk brought up to date for the AbCriterati: Ms Knee seems to have snuck into Mr Greenwood’s writing room and made free with his style

LikeLike

Who wants absolutes?

Do you think perhaps that the difference that you refer to in the Post-everything world of art, compared with even the most limited phases of the recent past of modernism, is that artists don’t any longer work to any kind of visual imperative whatsoever – in fact, they (and you?) wouldn’t even understand what was meant by the term – but work instead to the fulfilment of their own subjective and nuanced interpretations of fashionable conceptual and philosophical criteria, which in fact have no real connection with the long and wonderful history of real visual art.

We are Post-visual. Well, I’m not, but perhaps you are?

LikeLike

Carl has said it better than anyone could! Kindred spirits of the world unite. I even share his taste in Jazz.

LikeLike

Shaun,

“Visual imperative” I suppose means something along these lines: despite taking decisions and making adjustments in painting and sculpture for all sorts of different reasons, serious visual artists are driven to make the work come together, make sense, and work as a whole by criteria that are arrived at by looking (how it looks/works) rather than by conceptual preordination. These criteria are felt to be compulsive and inescapable; they are what drive the direction of the artists’ work. Yet these criteria can be wildly different in different artists – for example, the seemingly relaxed and loose assembling of parts in some Manet paintings compared to the obsessive finessing of every last fitting together of detail in certain Cezanne still lives – but both examples exist in the same world of visual sensation and judgement. They are related, no matter how apparently different, by an endeavour to make something that “looks good” (which is a weak way of putting it, and something we can argue over endlessly, and is certainly not concerned with absolutes), and which connects them with, and makes them comparable to, the whole of the history of visual art.

By contrast, conceptual art and much Post-modernist art, e.g. work such as Helen Marten’s, are not connected to the history of visual art in quite this way, other than historically, and there is not really any point in trying to make a visual link or a comparison. Marten’s criteria are only very marginally visual, if at all, even though she is described as someone obsessed with the craftsmanship of beautifully made objects. Such works as hers, with no visual ambitions other than to “Surreally” collage together anomalous and weird literal objects and materials, are in themselves anomalies in the history of art; such anomalies have happened before, though perhaps not so universally. Such things will pass, hopefully, and a reconnection (or continuation) with all things visual will be made. I think maybe “continuation” is a better, more realistic word than “improvement”.

LikeLike

Sure things are different from 1950s New York. You may have noticed I’m quite critical of a lot of that stuff. I want to move on with abstract art, but not at the expense of what is visual. That’s my thing, you have to suit yourself. I’ve said enough.

LikeLike

“It’s almost impossible to be specific, and this really gets up the noses of people who want absolutes in life.”

I would like to seize on Shaun’s use of the word “specific” here. I think that the importance that art has in our lives – it’s value, why it’s worth doing and taking an interest in – has everything to do with specificity. (And no definition of art that fails to account for its importance and value to us humans can be a definition of ART.) It seems to me that no other kind of thing in the world is specific in the way that a work of art is specific because our interest in it is in just THIS thing, right here and now, why it is EXACTLY as it is to a specific person, namely me or you or whoever is experiencing it. (The experience of art, to its maker or to its audience, has to do with selfhood and its achievement.) About a work of art, we ask, “why is it, in every detail, the way that it is?”

Try describing your interest in a sculpture by Michelangelo or Rodin, or a painting by any great artist without being specific in your description. Impossible.

I have no idea if Jeff Koons (for example) is considered “post-modernist”, but I can describe a Koons sculpture without being specific. Similarly, I can describe an art work that is meant to illustrate some theory or other without specificity because I’m really describing the theory and all theories are general or they aren’t theories at all. I can describe a Duchamp without specificity for instance.

This leads to the thought that if it can be described without specificity, it’s probably not a work of art – meaning, it doesn’t elicit the kind of interest or have the kind of value that has always been associated with great works of art. Art has to do with experience (making or viewing) and experience is always specific.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think I agree with most of that, though I think it is impossible/pointless to say what is and what is not art, only what you think is good or bad painting or sculpture, and perhaps why.

Not sure either that all theories are general, but perhaps it’s right to say that all art that illustrates rather than embodies a theory, or anything else, will lack specificness.

LikeLike

Do you not think it possible that Michelangelo and Rodin had, as fellow human beings and artists something in common with us that is more fundamental than either their or our contexts? And that that something more fundamental will still be there in artists of the future whatever their contexts will be? In my view those who value context above all else in their creative pursuits should understand that the dynamic of context alters and fast in our modern age. Fashion and novelty become kings, the things that have to be kept pace with in the pursuit of vain, shifting relevance. .

LikeLike

Robin, I agree with your first sentence entirely. Saying why an art work is good would be to say why and how it is art at all. (I should have written: “a theory [not ‘definition’] of art that fails to account for its importance FOR US… is not a theory of ART…”).

LikeLike

Discussing this Pissarro on Twitter

LikeLike

I don’t think abstract painting can compete with a truly fine landscape, but the process of working (in the abstract) is so different and points to a freer, expansive improvisation and engagement that can make the pursuit very compelling.

LikeLike

I don’t agree with this Noela. I think that some abstract paintings (like some impressionist landscapes, including a good portion of Pissarro’s) are overwhelmingly beautiful. I have no reason to believe that abstract art cannot compete with any art of any time and any genre, although I suspect that “compete” is not a very useful term in understanding the power of which art is capable through the ages. I wonder why it is that most discussions of impressionism tend to marginalize Pissarro in favor of a few more prestigious names. Could it be that Pissarro’s paintings are so incredibly effective at portraying deep space while at the same time gathering their effects at the surface, and this runs counter to the standard story of modernist painting?

LikeLike

Carl I feel a landscape offers something so different from an abstract painting that it cannot ‘compete’ with it, so I am not really disagreeing with you. I also think I am approaching the whole thing from the ‘doing’ rather than the ‘viewing’ point . However, I can probably bring to mind more beautiful landscapes than abstract paintings, but of course a lot of good abstract paintings aren’t about looking beautiful.

LikeLike

Perhaps beauty isn’t a particularly good criteria, and it certainly isn’t the only one. Then again, pressure, tension, intentionality can all be “beautiful”, though not necessarily in a conventionally “aesthetic” way.

Carl rails at “competing” with figurative painting, but it’s a spur to up the game. Maybe that’s just for artists, but in my mind, abstract sculpture has already sidelined figurative sculpture by doing more spatially than it ever could do. Maybe it’s true for abstract painting too and I just don’t see it yet. But you look at that Pissarro and it’s such a rich, complex, coherent thing…

LikeLike

A quick comment or two.

There’s more space between the shoulders of one of Bruce Gagnier’s figure sculptures than there is in all England. Artists ARE competitive—just like politicians, just like everybody—but they’re a little different too: the “game” they’re playing lasts a long time, and maybe there are no sidelines, at least not for the important players. Spatiality is important. Specificity is important too. I sent Carl’s comment about the word “specific” to Bruce. Here’s the reply I got:

“This is very original and powerful . Very much to the point and an entirely new way to describe the problem. sometimes perhaps when people are in difficult positions in Art , take on problems that are not wafted in the wings of success, they must think harder than the smooth ones and often as in this come up with important answers. Bravo to whoever wrote it! We want to be specific, absolutely so and the problem is made even more difficult when the content around which the forms must wrap themselves is evanescent. Thanks for sending it. I think my large figures are becoming more specific but the specificity can not be explained in a simple sound bite. This kind of writing with is singular focus is rare also rare is the daring it takes to bite into the problem so directly.”

There are one or two people in the world who might not know Bruce. Here’s a link to a nice introduction: http://www.arteidolia.com/interview-bruce-gagnier-christine-hughes-donald-martineaw-vega/#sthash.lZwdxaVD.dpbs.

Lots of great stuff in this “thread”—“competition” between abstract and figurative, between abstract and literal, between painting and sculpture—getting closer to the “competition”/”tension” between form and content too. . .

LikeLike

Keep em coming. Only eighty odd to go to equal Bunker on the A.E.s. Pity it’s all so “abstract” though. Some of the worst painting in the world is highly “specific” and in its spatial depth, without having any emotional “depth” or formal strength. All,of this talk is mere speculation unless you point to examples. I agree about that Pissarro , of course I would, but you have yet to account for how that depth is compatible with abstraction in painting, a question I have been wrestling with for many years, but in paint, not in words.

LikeLiked by 2 people

But you have suggested, have you not, that abstract painting can work spatially “outward”, into the room, rather than back into illusionistic space.

Seems to me in that great Pissarro that we physically understand the lie of the land and the space/distance involved and believe in all that simultaneously with believing in the coherent visual organisation of the painting’s two-dimensionally. So in effect the physicality of the landscape is made visual, and the duality/tension is (almost) resolved.

And in most abstract painting that goes for deep space/holes, it just rankles…

LikeLike

…and bringing the rising path up the right-hand side to a near-vertical position – just how genius is that?

LikeLike

Only in America would Marcel Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase have been considered radical or avant-grade — an academicised misreading of the genuinely plastic art of Braque and Picasso’s cubism, combined with a trompe l’oeil rendering of stop motion photography. (See his early academic portraits in Philadelphia). Duchamp was one of the few “painters” to be influenced by the science of optics, which he discovered can only be represented diagramatically on a flat surface, I.e. Illustrated. Hence his last 2D work, gifted to Walter Arensburg, housed in the Philadelphia Museum is just a compendium of graphic devices, so much like the post-modern , post-pop idiom of Polke, Oehlen and co. The only solution was to stand aside from seriously engaged painting and sculpture, and pose as a superior intellect, pipe and slippers, with the banality that anything in the world can be viewed aesthetically, which every painter already knew, but which the great public seemed and still seems to regard as a revelation. Hence Turner-prize art!

LikeLike

A letter in this weekend’s Guardian from James Hall linked Duchamp and his crappy last work “Etant Donnes” with the worst of the Pre-Raphaelites (Duchamp apparently identified with Holman Hunt’s “Light of the World”). The crap goes round and round.

LikeLike

“Her refined craft and intellectual precision address our relationship to objects and materials in a digital age,” said Simon Wallis, Director of the Hepworth Wakefield, speaking of Helen Martin’s winning work.

Perhaps the wrong kind of specificness?

LikeLike

There is a clear demonstration of the mechanics of how spatial illusionism/cum/ rich surface tapestry of Monet’s Nympheas is created — in a ridiculously heightened colour detail of the central portion (squarish) of one of the Orangerie paintings (a dark one) available on Google. At the same time it shows its kinship with the perspective of his early Boulevard Des Capuchines 1873 (Pushkin Museum), and Pissarro’s late recapitulation on that theme in his own late Boulevards.

The whole right hand zone of this detail has a subtly disguised perspectival recession accentuated by the gradually enlarging of the wonderfully animated brush-strokes from its inward most projection to its “nearer” areas, (just as occurs in Matisse’s Baroness Gourgaud and Interior with Phonograph). Then the left hand zones pull away and out from this recession in broad swathes of atmospheric colour in aerial perspective. And all this achieved without breaking the rich tapestry. The surface is thus claimed as physically real, present, palpable and stamped with the unique touch of the artist. This is where “presentness” originates. And without a hint of literalness.

But to do this now would be to imitate the inimitable, and immediately to be sensed as pastiche. This is the dilemma for abstraction, has been for quite a while.

LikeLike

Going back to Côtes des Boefs (there´s an incredibly detailed version at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_C%C3%B4te_des_B%C5%93ufs_at_L%E2%80%99Hermitage – keep clicking on the image… ), it seems to me that most of what Pissarro is doing in a painterly (and perhaps therefore abstract) sense is working AGAINST the figurative space.

The warm white of the almond blossoms (?) at the lower right helps to bring them forward compared to the cold white of the building directly behind. Here Pissarro is working WITH and accentuating the figurative space.

But there are loads of instances that go in the other direction:

Look at the green patch in front of the almonds – it is distinctly cooler than the green visible through the stems. Here, I imagine, he is getting the bottom of the painting to recede slightly in order to preserve the flatness of the picture plane.

The strong verticals of the trees would normally push whatever is behind far into the distance, but here they are disrupted everywhere by tiny incursions of the background. This is particularly noticeable in the sky, where white and blue are forever overlapping the browns and yellows of the branches. (Soutine does this very obviously in his tree paintings.) Wherever this is not enough, traces of warm Naples yellow and pink are worked into the sky to bring it forward.

The two saplings in the foreground establish an important part of the figurative space but are held back by little overlaps in a similar way. And following the left-most branch of the first sapling, see how it is almost savagely pegged back by a part of the house wall above the blue door. So effectively that the trunk of the tree alongside needs a reddish brushstroke at this height to preserve the space between house and tree.

The distant trees on the far right actually run over the branches of the foreground saplings in places.

There are lots of other examples, but I´ll stop there. It seems to me that it is this “painting against the figuration” that creates the tension and duality between space and surface. With the figurative image pulling strongly into the picture´s depths, it is straightforward (though not easy) to create a painterly resistance to preserve the surface.

In abstract painting, this overall pull is missing and in order to create the same kind of tension between surface and depth the artist has to use very similar painterly devices in BOTH directions. This can very quickly become confusing and/or incoherent. I think this may be the main problem when it comes to abstract painting and spatiality, and maybe also the reason why many give up and resort to chasing only flatness or only space.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Amazed that you can see all this from a reproduction on the screen, but I expect you have it pretty much right. I never look that closely at paintings –prefer just to go with them as a whole. I think what you are talking about is what Pissarro calls “passage”, the colour definition of areas taking on some of the lustre from adjacent areas. If ever I was asked to do an Artist’s Eye selection at the Nat.Gallery, this would be one of my centre pieces, and then I might have a chance to scrutinise it the way you have. Or have you been to see it recently?

LikeLike

No, not recently, and I’m sure there’s lots more going on with surface texture etc. but I think you can see the things I mention when the resolution is large enough on a screen.

Thanks for calling attention to Pissarro and this picture. I wouldn’t have looked otherwise.

LikeLike

If I’m understanding Richard’s post correctly he is suggesting closer inspection of small areas of the painting (what you refer to as ‘the exercise’?) in order that we might get a better understanding of how Pissaro is manipulating the illusion of space through the use of colour. It is not difficult to understand why and how (the latter being the point of the exercise) this would be of interest to abstract painters who don’t want to directly exploit what you refer to as our normal day to day perception of space but who also see insistence on flatness as either a dead-end or just boring. I’m not an experienced painter but what Richard is describing so illuminatingly seems pretty much to equate to the ‘push pull, spacial feel but it is just so enriched by virtue of the fact that it is a figurative painting. .

LikeLike