This isn’t going to be a review of the Tate’s Rauschenberg show. I’m more than a little disappointed that it includes so few of his “Combine” works from the fifties. I was hoping for many more in order to justify my long-held belief that Rauschenberg possessed a genuine visual talent, a “good eye”, which I had hoped seeing more of his best paintings would confirm. I think he had a natural gift for putting all sorts of stuff together that shouldn’t really go together, in a manner that challenged some of the orthodoxies of abstract painting, making things that looked good and worked in concert. Despite all the oddball stuff he got up to both before and after the “Combine” period, I’ve held on to this opinion for a long time, based upon things of his I’ve occasionally seen around, but also upon reproductions. And of course I was hoping that the Tate show would afford the opportunity to confirm my view in front of the real things. Some chance, and the fact that it doesn’t is indicative of the low priority all things visual get these days. Tate gives equal weighting to all the different phases of Rauschenberg’s career, which might be thought of as only reasonable and objective, were it not for the fact that most stuff before and after the “Combines” is poor, and mostly non-visual; so that, in fact, a more objective appraisal would necessarily have privileged the “Combines”. Obviously it would be out of the question for Tate curators to make such a call on their judgement.

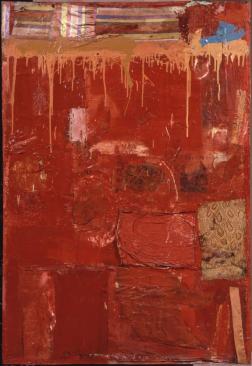

Here’s a selection of some Rauschenbergs from the fifties that are NOT in the show (click to enlarge):

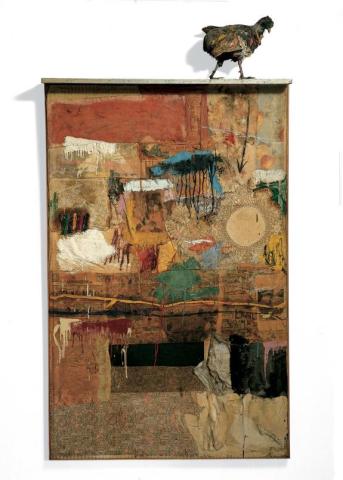

I like the look of all of these, in reproduction; but the only “Combine” that I like that is actually on view at Tate is “Charlene”:

Rather annoyingly, this work features an electric light that flashes on and off. If you get someone to stand in front of the light and mask it from sight, you can get a measure of how coherent this work is, despite its seeming incongruities. In my opinion, Rauschenberg successfully integrates all the “found” elements in this piece into the pictorial content of the work. Rauschenberg may possibly owe much to de Kooning’s work from this period, but it seems to me that the achievement of “Charlene”, in particular the large centre-left panel, is something well beyond the achievements of de Kooning, even at his best:

The problem I always have with de Kooning – which applies to all his works now in the RA show – is that no matter what mode he is in, figurative or semi-abstract, his work is dependent to a very large degree upon drawing. He’s forever slathering the paint about with a brush in a linear fashion (even in the big “abstract” landscapes it happens, albeit with a bigger brush). I’ve never really got on with this in any artist, figurative or abstract. Now look at “Charlene” again and note the complete absence of drawing, the total integration of spatiality of different kinds, as colour upon colour melds itself into form in a properly painterly and pictorial manner.

The one really interesting large painting in the show, “Ace”, 1962, makes for a good comparison (available now in London) with the large multi-panel Joan Mitchell at the RA Ab-Ex show, “Salut Tom”, 1979:

Whilst I think the Rauschenberg is eminently criticisable, not least for some of its rather unintegrated empty spaces, it seems to me more exciting, radical and whole than the Mitchell, which has a rather bloated and unconvincing look of acres of canvas being just barely filled, with compositionally over-calculated shapes (mainly rectangles), with the areas of paint and its handling dictated to by a rather vapid aesthetic (I’ve elsewhere on Abcrit already compared this Mitchell to the adjacent Hofmann, and criticised “her sloppy and supposedly ‘expressive’ brushwork”). I’d rather have “Ace” to look at because it opens out spaces in a much more diverse and uncalculated way – perhaps even a much more abstract way – than the Mitchell.

Beyond that, I can’t say too much more that is positive about the show. Rauschenberg’s sculpture is embarrassingly bad throughout, and his “eye” seems to work exclusively in pictorial mode. But that’s fine, and you can get glimpses of it still in operation right through to the end of the show – but by then the real involvement with the nitty-gritty of painting-making has gone. He becomes detached from the materiality of stuff and detached from the “shoot-from-the-hip” decision-making that he seemed to have excelled at when making the best of the “Combines”. With the Ab-Exes in town, what a good moment it would have been to see more of these works. I can only really speculatively suggest that they would have been quite a challenge to the stifling pompous formality of Newman, Still, Rothko et al. Perhaps even to Hofmann.

They might also have proved a lesson for the paramount artist de nos jours, Helen Marten. It seems to me her work is extremely indebted to Rauschenbergs “Combines”, though I haven’t seen it mentioned in any reviews. And though we can’t blame him for Marten’s extreme shortcomings in the sculpture department, that debt ought to be noted. It also needs to be said that she is completely without the visual talent that I see operating in Rauschenberg’s best work. Her work certainly has an aesthetic, but that’s never enough, and I’ve read too that it has complexity and meaning; but what makes it fall dead to my eyes is the lack of engagement that so typifies the “Combines”, wherein the decisions made “live” are seemingly embodied in the work, and simultaneously made to operate “all of a piece”. That may or may not be an illusion, but it seems to me vital to communicate a sense of human content and endeavour to the work. Without it, Marten looks like nothing more than an overcomplicated Surrealist, full of weird juxtapositions that don’t gel. Her decision-making is not visual.

Rauschenberg doesn’t escape criticism. Some of the few “Combines” that ARE at Tate don’t work for me at all; and then there is the big question of why he didn’t stick at it. He seems to have been a rather garrulous and eclectic sort of a chap, and I guess the fashions of the day took him away from where I think his real talent lay. Fashion in art makes for all sorts of anomalies. Here’s a Rauschenberg from 1959, “Summerstorm”, that I think looks terrific, perhaps one of his best. I would love to have seen this work for real. Incidentally, I haven’t mentioned colour hardly at all, but I think the colour in this painting is great:

Out of interest, I follow it with work by other artists from the same year, 1959, upon which I make no comment at this stage. Perhaps other commenters will feel some comparisons are called for…

Rauschenberg website: http://www.rauschenbergfoundation.org/art/series/combine

Rauschenberg at Tate Modern runs to 2 April 2017: http://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-modern/exhibition/robert-rauschenberg

Helen Marten gets a mention here: http://www.conceptualfinearts.com/cfa/2016/12/09/who-is-the-most-influential-visual-artist-of-the-late-twentieth-century/

LikeLike

I read the Guardian: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2016/nov/22/helen-marten-from-a-macclesfield-garage-to-artist-of-the-year?CMP=share_btn_tw No mention of Rauschenberg here.

LikeLike

Thank you Robin for posting some great images of Rauschenberg’s work, most of these I have never seen.

I can’t say that I was besotted by his work but I can say that when I began my foundation studies in Art in 2000, Rauschenberg’s work grabbed me immediately. His combines seemed raw, real and expansive. I think these works for me are important because they seemingly unknowingly or in a light and playful way combine so many layers of painterly ideas. Representation, flat picture plane, portrait, landscape, grid, still life and how we view a painting in the modern age. Bringing these works to my attention again has reignited this initial excitement I had when I first saw ‘Canyon’ or ‘Charlene’.

In what I have read and heard in interviews, Rauschenberg appeared to hold the Abstract Expressionist’s in high esteem. I think he once said that he wished that he could paint like De Kooning! I think this was in a late Charlie Rose interview regarding his retrospective at MOMA.

It seems he was a restless talent in exciting times, maybe he got swept along by this. You certainly couldn’t call him a one trick pony a la Clifford Still!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Rauschenberg’s retrospective was at Guggenheim not MOMA.

LikeLike

” … Like sodden cardboard packaging in a leaf laden park fountain that’s been turned off for the winter”.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Sounds like late Monet water lilies.

LikeLike

Rauschenberg is a typical product of American academe — an exemplary student who has been to too many slide-shows by academics (like David Sweet), tracing the origins of cubism etc. He has all the cubist tricks, but without the organising principle, plastic or volumetric. Hence his collages are a compendium of every graphic, pictorial and painterly device, (very post-modern) culled from cubism and abstract expressionism, (of course he wishes he could paint like them, but lacks the gift to be simple, and the balls). His one contribution is spatial dislocation, a disorganising, breaking the total image up into unconnected cells, and abrupt changes in scale, and unconnected spatial illusionistic devices, ( I.e. The convex-concave hollowing out with black to white shading on the left of Ace)….. All very clever, but all that holds them together is a dingy, dirty brown tonality which I for one find viscerally repellent. I prefer the Joan Mitchell any day, with all its faults.

And Robin has fallen into the Penelope Curtis post-historic trap of curating works arbitrarily, all of the same date, obscuring the fact that Rauschenberg was plundering Hofmann, Rothko’s Multiforms of 1947-48, and much else besides.

LikeLike

When I experience in close proximity a DeKooning i.e face to face not in reproduction, that experience is often akin to watching a great pianist performing a Beethoven concerto.There is a tension in the gestures and facial expressions that indicate that the pianist is trying to hold all the parts together so that they add up to a metaphysical whole. That there are some DeKooning paintings that are a little flaccid only makes the great ones greater. Rauschenberg’s introduction of Duchampian objects seems to say that the visual object i.e. one that is experienced as Baxandall says of Caravaggio inside the eye/mind is no different than the real object. It is a nihilist trope to make us an object among objects. The clash of the two realities does result in some exciting visual events.But as Gouk says they are very clever. In another essay on this show Hande writes in what must be a typo that Rauschenberg “pre-empties” Hirst and Emins. That is in fact his goal: to empty out of painting all metaphysical meaning. He has given permission to the shake and bake, scratch and sniff painting that so permeates the world of contemporary abstraction. Here is a short essay on what DeKooning is doing in his work to hold all the parts together :http://martinmugar.blogspot.com/2012/02/starting-with-anthony-powell-and-ending.html

LikeLiked by 1 person

A show-off list of great pianists I’ve heard playing Beethoven live – Annie Fischer, Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli, Sviatoslav Richter, Claudio Arrau, Daniel Barenboim, Alfred Brendel, Ivo Pogorelich, Maurizio Pollini, Jorge Bolet, Murray Perahia, Martha Argerich, Shura Cherkassky, to name the ones that spring to mind. I can’t honestly recall being much interested in the faces or gestures of any these pianists, except in the case of Cherkassky, who seemed quite amusingly mad. If the tension is not to be heard in the music, and the wholeness is not also to be felt in the music, it has no bearing that I can understand. The fact that the music is being performed live is certainly important to that tension and resolution, but that’s not metaphysics.

That Rauschenberg clears out the metaphysics from paintings containing pictorially integrated objects is greatly to his credit. It makes the meaning available to the eye, and it makes Rauschenberg fundamentally different from an artist like, say, Joseph Cornell. And you can’t blame Rauschenberg or any artist for what comes after. He doesn’t “give permission” for anything. It seems to me that your charge of Nihilism and the link to Duchamp is a false reading, and that your own painting methodology owes more to Dada than Rauschenberg’s, at least as far as the “Combines” are concerned. I make no defence whatsoever of the rest of his output.

LikeLike

Oh heck! But “…Rauschenberg pre-emptied him” sounds great to me too. I have asked the CFA editor to correct this. By the way, your typo is Hande (should be Hands of course).

LikeLike

The principle of composition in a Rauschenberg picture is aggregation or combination (as opposed to, say, organic growth and development). Aggregation/combination/juxtaposition presupposes the prior existence of what is put together. Usually what is put together are something like “styles” of contemporary painting (abstract expressionist brush work, pop art images, grids, etc.). But if those things have prior existence, it is because they have become ossified, like manners or settled conventions. Rauschenberg is celebrated for his “eclecticism” in this way, and he was prescient of so-called post-modernist “appropriation and sampling” – but in my opinion it is better seen as a confession of weakness, a lack of commitment to the enterprise of painting. When a “style” is “appropriated” and combined with other “styles” in a single picture, it has become literal, like a tool to be utilized in certain way. (I think of the way Picasso was able to churn out an endless series of “Picassos” after about 1930. His very facility was a confession that he was finished as an artist.) I think the comparison of “Summerstorm” with the sublime “Saraband” says it all.

LikeLike

Strange logic – how is using, say, a bird’s wing in a painting an appropriation of style? And even if it was such, all artists appropriate. It doesn’t mean a lack of commitment to painting. As for the sublime, you can keep it, thanks.

And for the record, late Picasso – say 1965-72 – is one of his greatest periods.The show at Tate in 1988 of late works rivalled and possibly surpassed the Hofmann show of the same year and venue.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Rauschenberg’s aggregation of contemporary ways of making paintings reduces those ways to “styles”, that is, mannered techniques that exist not by virtue of individual paintings but by virtue of settled and accepted conventions. In that way, those styles have ceased to be artistic media and have become as literal as the bird wings, clocks, electric light bulbs and other non-painterly things that are inserted into his pictures. I find it almost impossible to believe that you seriously prefer Rauschenberg over Louis’s Saraband, which is a real masterpiece of 20th century painting.

LikeLike

In fact, I would say that the significance of Rauschenberg’s insertion of non-painterly objects into this pictures is exactly to signal and confirm his understanding that contemporary ways of making paintings had become mere techniques that could be used (like a set of literal tools lying on a work bench) to create objects that are interesting, as a commentary on painting can be interesting but never compelling as only a work of art can be compelling. This accounts for the smugness, the all-knowing attitude of “meta-painting” that Rauchenberg’s objects exude. A theory can never be as convincing as the reality that it purports to explain.

LikeLike

It is always going to be difficult to successfully integrate an everyday meaningful object like a tie or mangy bird into a visual work of art. But it is silly to say you never could. However, the bird or tie, in a sense, and at times, will need to disappear as it successfully integrates with the rest of the work. How different is that from how a distinct piece/passage of paint successfully integrates? There are at least similarities.

If we get stuck on seeing the tie, mangy birds or an area of paint, if any area just doesn’t work, the painting/combine/work fails. Or alternatively the viewer fails.

Perhaps Rauschenberg had a natural visual skill with which he probably wasn’t that bothered about focusing on and developing, much like de Kooning (and indeed others)?

Perhaps they both share an ability, or have interests, that distracts them from what something really looked like?

LikeLike

Carl

We may have been here before, but I´d like to hear your reasoning on this again.

To contend that artistic conventions can become “used up” seems to me to deny the uniqueness of individual artists. A good set of conventions is surely transparent to individual experience, allowing any number of artists to achieve non-objecthood / human content / grace within those conventions.

It may be that later generations detect a supposed method behind an innovative artist´s successful work, which is then regarded as a new convention, but unless he or she is deliberately looking to break with convention as an end in itself, their working “at the time” is within a received set of conventions and none the worse for that.

And it seems to me that the conscious attempt to break with convention is a poor strategy for making art, leading to intellectual “solutions” or the illustration thereof rather than a compelling vision of reality / expression of being.

I´ve not seen Saraband (or any of the Veils) and I´m not too keen on assemblages so this is only a theoretical judgement, but to my mind “Summerstorm”, on account of the density and particularity of the decision-making involved, has a much greater chance of escaping objecthood than skeins of poured colour.

LikeLike

I was fortunate enough to see both of these shows (just flicking through the Picasso catalogue that I keep in my studio, as I write this) and see evidence of an all consuming passion to paint. To invent, repeat and re-invent through the process of continuously painting/drawing. This is evidence of a “confession” of love for painting, for being alive and to push his own particular obsession with a visual manifestation of his lived experience. The images are provocative – not only the sexually explicit content – but the space entangling, indicative flatness of a particular kind of illusionism, and an explorative formation of forms within the compositions. These images are never exhausted. Take a look at ‘Reclining Nude’ (7 September 1971) (page 233 in the catalogue). Picasso’s works seem to oblige the viewer to add, but never complete, the experience of looking/living in the world – not abstractly, but in concrete terms.

I quite like Hoffmann too…

LikeLiked by 2 people

Almost in total agreement with Carl’s analysis.

LikeLike

But check out Picasso’s Women at their Toilette 1938, and ask whether Rauschenberg has added anything at all.

LikeLike

And I can’t believe that you are, and know that you are not being serious in comparing a Nympheas to “sodden cardboard packaging,” cos if you are you’re as far off the mark as Bunker. Whereas Rauschenberg is very like, and literally too. If that’s what you mean by content, sticking dead birds , ties and bric-a-brac onto the surface and spattering them with paint,….Oh dear!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Compare Picasso’s Violin at a Cafe 1913. It’s all there, minus the dead bird.

LikeLike

That’s it! So glad you’ve finally understood abstract content. Stick a bird on it! What a relief you’ve finally twigged. I realise dead birds might be scarce up your way, but you surely have plenty of old ties. Get ’em on.

Which Rauschenberg are you comparing to “Violon au cafe, sans oiseau mort”? One thing Rauschenberg avoids rather well on the whole is the Cubist trope of sticking a figure/image thing right in the middle of the picture.

LikeLiked by 2 people

In all seriousness, I’m not much of a fan of late Monet, as you know. I’m not sure which Water Lilies you favour, but the ones in the Orangerie I really dislike. I recall the Reader’s Digest Collection years ago had a good one, but the little Cezanne they had shaded it..

LikeLike

Regarding Richard Ward’s comments:

“To contend that artistic conventions can become “used up” seems to me to deny the uniqueness of individual artists.”

On the contrary, it seems to me that when a set of conventions have become “used up” – meaning, they lose their naturalness and truthfulness, so that they have become “mere conventions” (and an artist who bows to them is understood as “conventional”) – it becomes absolutely crucial for an artist to insist on his or her uniqueness, because the task is then to discover for oneself a relationship to this history of his or her art (e.g., painting, sculpture) that is not longer provided or guaranteed by convention (aka tradition). Modernism means that art has lost its natural connection to its own history, so that the connection must be re-discovered or the art will die. It appears to me that Rauschenberg has no problem with his activities having lost their connection with the history of painting and that’s what his pictures are about. Equally, it appears to me that Morris Louis viewed such recovery of connection (in the absence of authoritative conventions) as a matter of life and death – not only for his art but for himself personally (i.e., his life had no meaning apart from painting).

“And it seems to me that the conscious attempt to break with convention is a poor strategy for making art, leading to intellectual “solutions” or the illustration thereof rather than a compelling vision of reality / expression of being.”

I agree with this entirely. An avant-gardist like Rauschenberg’s life work amounts to a conscious attempt to break with convention (i.e., with the history of painting), but for that very reason it manages not to actually break with convention as be irrelevant to it. I believe that the highest aspiration of a painter like Louis was to continue the art of painting, and to do that in the 1950s required that he had to invent new ways of making paintings – and in so doing, enable new ways of seeing those paintings made in the recent past (like Pollock’s and the Impressionists) that affected him most strongly.

“I´ve not seen Saraband (or any of the Veils) and I´m not too keen on assemblages so this is only a theoretical judgement, but to my mind “Summerstorm”, on account of the density and particularity of the decision-making involved, has a much greater chance of escaping objecthood than skeins of poured colour.”

It is I guess possible to see Saraband as an object featuring “skeins of poured color”, just as it is theoretically possible to see “Hamlet” as ink on paper but I think in that case, you wouldn’t actually be seeing it at all. On the other hand, it’s all but impossible NOT to see the necktie in Summerstorm as a necktie because that’s what it is.

LikeLike

“it’s all but impossible NOT to see the necktie in Summerstorm as a necktie because that’s what it is.”

But a line of poured paint is a line of poured paint.

Anyone can pour some paint or stick a necktie on a painting.

Neither of these comments are very helpful in judging whether something works and has value, or doesn’t.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Carl. I think our differences hang on what each of us sees as the meaning of “convention”.

I see a convention as a neutral and optional “rule of the game”, which might prove barren for a particular artist at a particular time so that if said artist continues with it, its use becomes a “mere convention” – a hollow appeal for recognition as art.

You seem to be using “convention” more specifically in this sense of “mere convention”.

LikeLike

Richard, I think of conventions as norms that as long as they are viable or active, provide us with a sense of what is normal, natural and appropriate. In other words, something much deeper than a contract or agreement. In this sense, conventions make possible not just our speaking with each other but our comprehensibility to one another. There is no logical necessity for instance in the ways in which we show sympathy for others by way of bodily language, eye contact and so on; therefore, these are conventions (but not agreements). But conventions can lose their force and so become “mere conventions” that may be rejected or become irrelevant or superfluous, etc., so that acceptance of them becomes conformity. I think the history of painting, sculpture and other arts shows how this happens.

LikeLike

This is once again fascinating reading! Are we going to get a rival to Turps banana Art School any time soon? Will there be a taxidermy course?

Joking aside. I am learning so much from abcrit, long may it continue!

LikeLike

LikeLiked by 3 people

Did you see what Geoff Hands wrote back there: “…the space entangling, indicative flatness of a particular kind of illusionism…”? How good a description is that of late Picasso? So much more involving than pure aesthetic beauty, don’t you think, Carl? I want engagement and dialogue with painting, not the distancing of the sublime.

By the way, Geoff, you may quite like Hofmann, but you need to learn how to spell his name. You and a million others.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I looked on my bookshelf for the Hof-person catalogue and it’s missing. I shall have to make do with my two Gouk publications for now! My typo on CFA (“pre-emptied” should be “pre-empted”) has been corrected.

LikeLike

I do not deny that Picasso did some good things after 1930; my comment was general and intended to make a point, namely, that when a way of making pictures has become facile, it ceases to be a medium of painting and becomes something like a technique or method, as a craftsman uses techniques and methods to create furniture and other objects. I think it is generally true that Picasso’s later work for the most part consisted of turning out “Picassos” as a craftsman turns out chairs. That observation does not deny his creativity, talent or passion for painting. It’s a point about the difference between literal objects and works of art. I do think the point is pertinent to understanding Rauschenberg’s objects.

I assume that your reference to “pure aesthetic beauty” is a reference to Morris Louis’s Veil pictures. Although they are ravishing to look at, I don’t think that this was Louis’s concern at all – it’s just that their sensuous look is so strong that it’s easy to miss what he was really try to accomplish, which had to do with using paint and canvas to provide a transformed experience of space in painting. In the veils, he tried (and succeeded in my view) to do this by using color alone, successive washes of pure color – without drawing, without lines – to achieve figuration and therefore open up space not so much in depth (which is the space of objects, because objects OCCUPY space) as in front of the picture plane – although our usual spatial concepts (‘in front of’, ‘behind’, ‘next to’ etc.) don’t really capture what it’s like to stand in front of one of Louis’s large veils (like Saraband, which I have seen many times, although not recently). I believe that for Louis, Pollock’s wandering, meandering lines, which do not describe or delimit objects, meant that traditional drawing was exhausted as a resource for painting, and that if the art of painting was to continue in his hands, the depth of feeling communicated in the representational pictures of the old masters would have to be resurrected by means of color alone. The unfurleds and stripes require a different analysis.

LikeLike

Late Picasso, “Large Heads”, 1969 – as posted on twitter by John P.

Don’t look too literal to me. It’s a challenge to just about everything in my Abcrit gallery, courtesy Emyr W.

https://pbs.twimg.com/media/Czlr9qPXgAESubV.jpg:large

LikeLike

Just picking up on the Richard/Carl dialogue – it seems to me that there are numberless shallow and dumb conventions in modernist painting, it’s full of them, so redundant that individuals wear them out almost immediately. Dripping, pouring, staining, striping… I could go on, they’ve all been mined out. There is, for example, nowhere to go with the dripping vertical runs of paint, as in the Poons. Likewise staining/pouring a big unprimed canvas. Nobody else can take that on and do anything with it (I know people do, but it’s pointless). In my opinion, the “Combines” avoid quite a lot of that conventionality. It’s true that even they don’t go on anywhere terribly new, but there is probably still more mileage in the way Rauschenberg painted than there is in the way Louis painted, because it’s a more open kind of content with which you can engage in a “conversation” of sorts.

LikeLike

I think seeing Rauschenberg as a postmodernist may be a bit anachronistic. In his day, amalgamating abstraction and figuration appeared to be a worthwhile rather than exhausted enterprise. He resembles de Kooning in that basic orientation. One way of holding on to figuration was to incorporate non-art objects in his work but, unlike Johns and Dine, in Rauschenberg such items are subject to dynamic formal processes. A necktie is a necktie, but its placement in the composition has been considered, and it makes a contribution to the variety of pictorial elements in the painting.

His main innovation was partition. He didn’t start with a rectangle, which he then divided. It’s rather that he put several unframed easel paintings together to create a larger work. He was then free to vary the contents of each picture. The objects start out bulky but are compelled, like the two fans and springs, to interact in terms of rhythm with the overtly painterly backdrop. By the mid-sixties however, they are replaced by other ‘extraneous’ components like lettering, signs and depleted photographic material, all of which are characteristically 2-dimensional. Because these are ‘images’, in other words figurative but surface-mounted, not ‘volumetric’, they are spatially neutral. They are then put to work in what appears much more like a pictorial environment associated with modernist abstraction, than the ‘flat-bed picture plane’, which allows heterogeneous elements to be fixed to the rigid base board of a faux relief.

Rauschenberg’s cynicism often comes up, his ironic attitude to the brushstroke. It’s true that he ‘performs’, but all the older generation of American painters ‘performed expressionism’. Expression has to be converted into a technique, or ceremony, if it is to be the basis of iterative practice.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Robin wrote: “It’s true that even they don’t go on anywhere terribly new, but there is probably still more mileage in the way Rauschenberg painted than there is in the way Louis painted, because it’s a more open kind of content with which you can engage in a “conversation” of sorts.”

Please describe the “content” of a Rauschenberg object. If it’s “content”, then describable in discursive terms, right?

Also, do you believe that Louis’s Saraband is more “conventional” than Rauschenberg’s Summerstorm (given the year they were both made, 1959)? Explain that, please.

LikeLike

Content is by no means necessarily or easily discursive. In fact it’s often difficult to discuss or describe, since it is bound up so completely in the visual values/relationships of a work, often of a very complex and/or subtle nature. In any case, if one were to undertake to describe the content, it would have to be of a specific work, not a generic “Rauschenberg”. But I don’t wish to undertake such a task. It’s best done with a few people stood in front of the actual work in order to make progress with that – as per Brancaster – and sometimes even that doesn’t work out. The better the work, and the more visual it really is, the harder it seems to be to discuss content. In the essay, I’ve said as much as I want to say about “Charlene”, the work I have seen and do like.

The point is that with a work of real visual content of quality and quantity, you would be able to return to the work again and again to slowly uncover different aspects of that content – though if you are doing it for yourself, you probably won’t be doing it in words at all. The words only come when you try to compare your own feelings about a work with someone else’s. And we have seen recently on this site how words can very easily obscure the content of a work, particularly if analogy and metaphor are used irresponsibly to describe abstract art.

Yes, I do believe “Saraband” is more conventional than “Summerstorm”, for two reasons. Firstly, the process Louis used to create the work is both repetitive and banal (I think you describe Rauschenberg’s methods thus, but I would reverse that. Rauschenberg’s work at least appears to be more spontaneously arrived at). As I’ve already said, Louis himself mined out this particular technique of the “Veils” and then moved on to another one. There just isn’t enough room or flexibility to the process to allow anything much to develop from it. It is part of a series which starts, based around one limited action – pouring in swathes – then stops, because there is nothing more to be done. You end up with perhaps a beautiful object, if you are lucky (an object of desire, indeed, for the rich, and part of a set of similar paintings – always reassuring for the punter), but even the artist himself cannot enter into anything other than the most minimal of dialogues with the work. Nothing can be changed or tweaked once the pouring is over, it either works first time or it doesn’t. You keep the good ones and chuck the duds.

Then, secondly, there is the fact that to my eyes “Saraband” is far more visually predictable and redundant than “Summerstorm”. There is not as much visual stimulation, variety, complexity or tension. The overt process of pouring is repeated again and again, is it not? Even its overtness becomes tiresome. I find it visually duller (though it’s one of the livelier “Veils”); therefore I find it more conventional to my eye. It has few surprises. Once I’ve got the idea, I’ve got the painting. OK, it’s nice to look at, a pleasing shape with good colour, but that’s it. I imagine I would be able to look at “Summerstorm” for a lot longer without getting bored.

The two reasons I give for conventionality are of course linked. What the artist does, in the end, is reflected in what the viewer gets. So now, it’s all about being ambitious for the actuality of the visual experience, its complexity and subtlety, its tensions in relation to its wholeness. “Saraband”, along with much minimalist abstract art of the period, has a simplistic notion of wholeness that has very little resonance. Abstract artists now cannot afford to get sucked into the aesthetics of an artist like Louis without being very wary of the seductions of such a process – the apparent ease of it (though I don’t doubt for a minute Louis struggled with his art). I think, therefore, that the high moral platform you build around high modernism, interesting though it is, and almost compelling in its reasoning, is a dangerous place for artists, should they be tempted; and they have to find ways to come back down to earth and restart abstract painting and sculpture in ways that are less rhetorical, more “open”. The “Combines” might just have more to offer in terms of “open-ness”, not necessarily in the inclusion of found elements, but in the dislocations of space that take place in some of the works, that upset the rather spurious “abstract” naturalism and dull rhythms of works like the large Mitchell; and much more importantly, in the intuitive adding and subtracting that appears to have gone into the process of their making (absent from the Louis), which seems to me to be intrinsic and fundamental to the activity of making progressive abstract art now.

LikeLiked by 1 person

“In any case, if one were to undertake to describe the content, it would have to be of a specific work, not a generic “Rauschenberg”. But I don’t wish to undertake such a task.”

When I asked the question, I knew the answer. The invitation still stands however with respect to “Summerstorm.”

“I think, therefore, that the high moral platform you build around high modernism, interesting though it is, and almost compelling in its reasoning, is a dangerous place for artists, should they be tempted; and they have to find ways to come back down to earth and restart abstract painting and sculpture in ways that are less rhetorical, more “open”.”

It’s hard to imagine painting more open and less rhetorical than Louis’s, at any stage of his career after 1954 – and Rauschenberg’s objects are at the opposite end of the spectrum in this regard.

I will try to do (very briefly) describe what I understand to be the “content” of a painting by Morris Louis.

Our ways of representing the world cannot now be seen as anything other than ways of making the world disappear from our presence, causing nature to withdraw. (Photography deals with this issue by restoring nature but at the price forcing our withdrawal from the world – this is the opposite of the attitude of modernist painters like Louis.) The reason is that our ways of representing the world have turned out to be ways of representing ourselves to the world – that is, rhetorical postures that manipulate, dominate, sentimentalize, distort, accuse, yell at, mock and so on. (For example, the methods used to establish perspective in representational painting has been revealed as a falsification of our relationship to reality, because perspective tends to cover up rather than reveal the nature of our distance from nature, our loss of naturalness. By covering up rather than revealing, perspective provides no way of reconnecting with what we have lost.)

Therefore, what is at stake in art like Louis’s is not to reproduce the appearance of nature, but something like nature itself, nature’s way of putting us in its presence – specifically, nature’s indifference to our rhetorical pleas and postures and its outlasting of us all. Viewing one of these pictures is like viewing a canyon or a cloud formation or a horizon or any other striking natural phenomenon. It makes me realize my scale and my place, the fact that if I’m not there (e.g., within the deep space of the a representational painting) it must be because I am here – in facing it as it faces me. This is what “openness” means. How does it face me? All at once, it is all there, every bit of it, every square centimeter of its surface, because it is all surface and nothing else. Louis’s pictures (together with Pollock’s) provide 20th and 21st century sensibilities with the closest thing to an experience of the sublime as we have discovered so far.

But Rauschenberg has some cool neckties and blinking light bulbs, tires and dead goats in his stuff.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Is the difference between these two maybe that Louis is trying (and by all accounts succeeding) to produce an effect in the viewer, a change in their spatial / perceptual / existential awareness, whereas Rauschenberg is trying to communicate something more particular and intimate of what it’s like to be alive?

Saraband would then be comparable to Anthony Gormley’s “Blind Light” or Eliasson’s “New York City Waterfalls” – providing a potentially mind-changing experience, but in an impersonal way. (At the time I described “Blind Light” to a friend as ” fairground stuff, but BRILLIANT fairground stuff”.)

That impersonality would explain why such works are also immune to further development, since they lack any purchase for individuality. As viewer, one is moved by them (one’s mind is blown) but cannot identify with them.

The response to the other, more intimate, kind of artwork is not so much a jolt to one’s perceptions as an indefinable sense of recognition – “yes, that’s exactly how it is!”

I think most artworks have a share of both of these qualities – Pollock’s drip paintings tending to the impersonal / awareness changing end of the spectrum and his earlier abstract-surreal paintings tending to the intimate /communicative side, for instance.

And maybe painting has had to hand on the torch when it comes to purely awareness-changing art, because the immersive technological possibilities of other media are so powerful.

That would be one sense in which (irrespective of quality) Rauschenberg rather than Louis might be more important to the future of painting.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Carl,

What you describe is not “content”, uplifting though it might be (for you). It’s a romantic metaphor for something approaching what one might better call “subject matter”.

I have no wish to do down your experience of Louis, but surely you can see how ruinous such an attitude would be for an abstract artist now. There are lots of artists who would agree with your reading of modernism, who think therefore that by minimal means they can achieve maximum returns by “bolting on” such a deep subject matter to their shallow activity. They are for the most part rank amateurs whose wishful thinking will achieve nothing original or significant (though none of us has any guarantee on that score). For an artist to presume to know all about the high-minded effect on the viewer of their work, such as you yourself experience in front of a Louis, would be conceited in the extreme – and we have plenty of that already, exemplified by artists such as James Turrell, Bill Viola and Marina Abramovic, who have by and large done away with the object altogether and just gone after the “sublime” thing.

Speaking personally, I like looking at art that has got something a little bit more to it than the sight of a striking natural phenomenon – good though that might be. I want to feel a communication from another human mind, but felt entirely through the quality and scope of their visual decision-making, entirely embodied in what is happening in front of your eyes. For that, you have to have plenty of “open” decision-making happening in the first place, so you can look at it, examine it, turn it over… And I want to feel it’s very definitely NOT about me.

And by the way, the “content” of the best figurative artists was certainly not to “reproduce the appearance of nature”. When figurative artists attempted “the sublime” they got in just as much of a mess as abstract artists. Compare this John Martin with Constable and feel the difference:

http://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/martin-the-great-day-of-his-wrath-n05613

http://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/constable-salisbury-cathedral-from-the-meadows-t13896

[Having written this, I see that it largely concurs with Richard’s latest comment.]

LikeLiked by 1 person

I don’t see how anyone can look at that wall of pictures created by Emyr ( how done? But brilliant) and say that the Rauschenberg has more to offer than the Louis, or the Hofmann. It looks like a running spool of cinematic stills jumped together. Jerky and irritating. Whereas the Louis is a commanding presence of spatial colour moulded by a simple unifying purpose. It’s only if one were to bring into the equasion a Monet Nympheas, such as the one in Oregon 1914-17, or the one in the Met., with the White strokes on blue violet etc, that the Louis would show its limitations. And of course Hofmann’s The Gate makes the Rauschenberg look as described in my first comment above. Thanks Emyr. Short of having all the pictures together in the same room, that’s the next best thing. So all this talk about content, interesting enough in its way, boils down to whether you can see the obvious differences in quality between these works, or whether you are deceiving yourself. On the whole Carl has it more right than wrong on this.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pat says the Louis is “gorgeous” and “velvety”. (My wife). Always listen to your wife.

LikeLike

I do. Mine says late Monet is crap.

A Constable six-footer would see ’em all off. How about, Emyr?

LikeLike

Well, my wife worships Monet. I worship Constable’s 6 footers!

LikeLike

LikeLiked by 2 people

Fascinating debate,

Funny that John Martin should come into this. When I saw “The Assuaging of the Waters” ( https://art.famsf.org/john-martin/assuaging-waters-198973 ) in San Francisco I thought, there you have it folks, the worst thing ever made by a human hand. Quite an achievement. But at least he puts it all on the table, and goes hell for leather in his corny pursuit of nature and humanity’s precarious relationship to it. At least we can get a legitimate laugh out of it. With Louis, Newman, Rothko etc. we’re supposed to treat this high minded existentialism so seriously, but I don’t think there is enough there to back it up.

I think what Richard wrote was really interesting, about the impersonal effect inducing experience of more minimal all encompassing work, and the personal communication of observed experience, that “Yes, that’s exactly how it is” feeling. My preference is for the latter. I find it more real and more lived in. I find the former very declarative, in that it presupposes the chosen technique (drips or pours) to in and of itself contain and reveal some kind of truth, possibly before it has even been done. This is one of the problems with the Veils or Pollock’s seminal works. You could easily explain what these works look like to someone who has not seen them. A giant spider tried to cast a web with motor oil. No shortage of insulting descriptions out there, mostly by Australians after the Blue Poles purchase. You could use hand gestures and give a pretty basic idea. Now try to say what is happening in Côte des Bœufs or Salisbury Cathedral, but without using the words landscape, rainbow or trees. It can be done but it takes more effort. Or try the Picasso without saying “Large Heads”. Can be done, but just not so simply.

Much of the discussion about Rauschenberg seems a touch prejudiced, because he’s one of the baddies who supposedly ruined everything. But when I look at the Untitled work from 1954 that Robin posted (the reddish square one with bits of mesh or whatever), I find it quite compelling. All these little overlaps of material and depth, nuanced surface and activity right out to the edges. It looks a serious painting/collage made by a serious artist/person. And if he does do some really atrociously bad stuff, like his eagle in the Met, well, I got a laugh out of it. Other more “discrete” elements, like the necktie or wing could perhaps be more thoroughly integrated, but I have to say I don’t notice them much in reproduction, though this could be because it’s all flattened out. I think they would very likely stand out much more in the flesh. But to just dismiss them for their identity as literal objects seems a bit unfair. Duchamp’s Fountain is a bad work of art because it is infallible. As a work of art it cannot be subject to criticism. The necktie in Summerstorm on the other hand is part of some larger conception filtered through the human mind, hand and the resistance of materials. It can fail, dramatically. But this also makes it more open. It is more open to criticism than a reduced gesture, a pretty pour, a seductive stain. These sorts of techniques have an anonymity about them that remove the risk of screwing everything up with personal intervention. No subjective weirdness, but not a lot of imagination either. Rauschenberg is also guilty of making annoying art that avoids serious contemplation and interrogation, when he makes something that is neither here nor there as a painting or sculpture, which is very often the case.

LikeLike

Bravo!

LikeLike

Carl just tweeted this image of a Louis:

So what striking natural phenomenon does this remind you of? How about applying one of your loquacious descriptions, Alan? What’s the content of this one?

LikeLike

Better ask Pat – she might remember the Napisan.

LikeLike

It brings to mind a striking natural phenomenon, but one that we have never encountered in the world. It reproduces not the look of nature (which is via the appearance of existing objects) but the way in which nature presents itself to us – frontally, immersively, inscrutably.

LikeLike

Sorry, Rauschenberg’s Eagle in MoMa, not the Met. Bloody “M”

LikeLike

Thanks Emyr. That’s brilliant. The Louis holds up pretty well actually, but it’s the substance of surface and physicality of the paint, all ” in the paint, ” , plus superb colour, colour and surface tangibly together that counts in the Monet. Sandwiching the Constable between them just reveals how far painting has come since the early 19th century, and that it is futile to look for aids to progress from there, except in the most general of ways, I.e. As to quality and depth of engagement ,which we all aspire to, but not formally. We simply are not led into the illusionistic depth of a painting the way we were in the 19th century. And we do not organise a painting in emulation of naturalistic light and dark in the old way. Is that loquacious enough for you.

LikeLike

And I simply don’t believe Sarah thinks late Monet is crap. She has too good an eye for that.

LikeLiked by 1 person

“I think what Richard wrote was really interesting, about the impersonal effect inducing experience of more minimal all encompassing work, and the personal communication of observed experience, that “Yes, that’s exactly how it is” feeling. My preference is for the latter. I find it more real and more lived in. I find the former very declarative, in that it presupposes the chosen technique (drips or pours) to in and of itself contain and reveal some kind of truth, possibly before it has even been done. This is one of the problems with the Veils or Pollock’s seminal works.”

I will have to re-read Richard’s comment. Regarding “more real and lived in” applied to Rauschenberg, that is exactly what I am missing but what I find in a work by Louis or Pollock for example. With Rauschenberg, I am a subject looking at an object. It may be an interesting object with lots of details that catch my attention (like a necktie, some “examples” or illustrations of AE brushwork, an image of JFK or some text, all combined), but it’s still an object like other objects I encounter in the world. It’s like looking at a fancy sports car with lots of gadgets on it. It doesn’t alter or make me question or challenge the kind of experience I have with objects every day.

But the problem is that we (or at least I because I can only speak for myself here) don’t live in reality. Perhaps people did in the past (when finding food to stay alive was real) but they don’t know. Today we live in irreality, or private fantasy, a world that “represented” and recycled on so many levels in so many ways that we’ve lost touch not only with reality but with ourselves. That is the fact that modernist painting and sculpture addresses and why it’s worth looking at. Another way to put it is: our relation to nature, to what is, has been distorted now we accept this as our world, and art, to the extent it can still be made, restores the connection. But it can only do so to the extent it dispenses with rhetorical terms – especially the sense of irony upon which Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns depends. Everything today is cynicism and irony and smugness; why produce more of it in art as post-modern art does? An artist must declare his or her relationship to what he or she experiences and stand by that declaration. To simply reflect it is to evade the entire problem. If that’s sufficient why do we need art at all? Duchamp and his followers (perhaps including Rauschenberg) thought we don’t need art. Speaking for myself, I disagree, and I’m not even an artist.

Perhaps this is why Louis’s and Pollock’s paintings strike you as too impersonal and as depending too much on a “chosen technique” like dripping or pouring. Could it be that these pictures require too much of you as a viewer whereas Rauschenberg’s demands are rather easily met? Also, remember that Pollock and Louis did not see their way of making paintings as mere “techniques”. It’s not as if just dripping or pouring paint on canvas can produce a Pollock or a Louis.

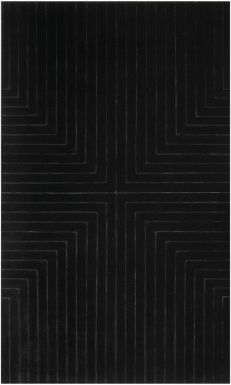

Finally, I believe that even the Frank Stella picture reproduced in Robin’s article is more valuable than any of the Rauschenbergs and will try to say why when I have more time.

LikeLike

The sentence in my post should say: “Another way to put it is: our relation to nature, to what is, has been so distorted that now we accept this [piles upon piles and feeds and broadcasts of representations and slogans and clichés] as our world, and art, to the extent it can still be made, restores the connection.”

LikeLike

“Sandwiching the Constable between them just reveals how far painting has come since the early 19th century”. Yeah right. You muppet!

LikeLike

Now let’s see, which Century were these done in?

Come a long way, have we?

LikeLike

Recognise the third one down, Alan? It was the one that knocked out the Monet in the Reader’s Digest Collection. Why, these are all nearly as good as Constable!

Late Monet and Louis are going nowhere.

LikeLike

“Late Monet and Louis are going nowhere.”

–Unlike Rauschenberg, who shows how easy it is to be an “artist.”

LikeLike

Cezanne is reputed to have wanted to do Poussin again ” after nature”. You seem to want us to do Cezanne again but not after nature. Take the nature out of Cezanne and you’re left with academic abstraction or neo -cubism. No-one admires Cezanne more than me, but I don’t want that. Just as with Monet, it is so obvious when someone is working out of them. There’s a lot of French art mid 20th century that does that, but I’m not going to mention it for fear of starting more copyists off. Just one — the early near monochromatic De Stael of the 1940s tries to bend cubist practices towards abstraction . There’s one in the collection of the National Galleries of Scotland. I used to quite like it in1962. But as De Stael became more “figurative” and at the same time “flatter” he arrived at Parc Des Prince (Les Grand Footballeurs) 1952. This exposed the perils of sitting in the in-between world. Cezanne’s paintings have the virtue of logic, and illogic , on their side. But they are not and never will be abstract. He is one of the most supreme painters that have ever lived, a colossus of painting. But you can’t force yourself into greatness with big intent. Either it’s in you or it isn’t. Be who you are, not what you wish you were.

LikeLike

Who knows the limits of what they can be? Only those without ambition.

It’s obviously futile to build a career as a copyist of another artist – Cézanne, Monet or anyone else – but that’s not the issue. The issue is whether the plastic and spatial values we see happening in the best figurative paintings are transferable to genuinely and unequivocally abstract art that has nothing whatsoever to do with abstractions from nature.

It’s worth speculating about what Cézanne meant when he said he wanted to “do” Poussin, but after nature, because he certainly didn’t show any signs of actually wanting to paint like him, and as far as I know never copied him.

I imagine that what Cézanne saw in Poussin was clarity and organisation of form of a kind that he wanted for himself, in which nothing is included that is arbitrary or contingent, where all the parts of the painting are locked together, yet in a way that keeps them alive to each other. In the paintings of both artists, both form and space are treated as truly plastic elements, to be reinvented and redefined at will, according to certain common visual imperatives, but insuppressibly under the sway of each artist’s sensibility. In Cézanne and Poussin (and for that matter Constable), all that we see in their paintings is plastic invention; and figurative though they may be, the imperatives are no less visual, in any sense that we can now comprehend, than those we might strive for in abstract art.

Is this then no longer relevant? Do our thoughts as abstract artists diverge eternally from this ambition? Are we now somewhere else? Perhaps so, and I just don’t get it. Is colour the thing that makes the difference? But those Cézannes are great colour. And anyway, I’m a sculptor.

By the way, now we have got to this rarefied altitude in the discussion, I’m no longer going to defend anything more about Rauschenberg – I’ve done my bit.

LikeLike

Carl,

I’ll have to be brief, I’m also a bit stuck for time. That the attitude of today is pervaded by smugness and cynicism is true, and I am certainly not a fan of Rauschenberg and Johns. But what I am able to do in regards to some of these particular Rauschenbergs that Robin has posted, is put whatever intentions R may have had out of my mind, and the context of the majority of his output for that matter, and simply see something of worth there. Whether or not he wanted to destroy art makes no difference to me in that moment.

So if I’m going to also put aside his intentions (what they might have been I’ve no idea), I also have to put aside the intentions of Louis and Pollock, who by the way I am not dismissing. Perhaps my lack of enthusiasm towards them is a failure on my part, and yet I feel that Pissarro and Cezanne provide far more of a challenge to my understanding of art and nature, and do reconnect me with the world. I look at them and say “Yes, that’s how it is”, and then my experience of their pictures informs and enriches my experience of sights and encounters within nature. With Pollock or Louis I feel more as though I am looking at an object. I feel more distanced from art and life. I become more detached and less enthusiastic about possibility in art, not as a rule but sometimes.

I’ll be interested to read what you say about the Stella, because that to me epitomises absolute death in art.

P.S. I read your take on Trump’s election and found it very compelling, so I see where you are coming from with the ‘irreality’ idea. I can very much see how such a state of affairs exists and has contributed to Trump’s victory, but I am struggling to understand just how Pollock, Louis, Stella even, stand in opposition to this. Or perhaps, why do they stand in more opposition to ‘irreality’ than any other great work of art from any period, today even. I am also unsure as to what extent it is art’s role to restore our connection to nature. Shouldn’t it firstly restore our connection to art, and offer possibility and the chance of continuance. “Die Fahne Hoch!” leaves us nothing to work with.

LikeLike

“I am also unsure as to what extent it is art’s role to restore our connection to nature. Shouldn’t it firstly restore our connection to art, and offer possibility and the chance of continuance.”

It seems to me that the role of art (whether it’s painting, sculpture, theater, poetry, etc.) has always been to forge and enable a connection to nature or what is considered real at any time in history. Otherwise, there’s no difference between art and decoration or entertainment. (In Northrop Frye’s book on Shakespeare called A Natural Perspective, I read that the Bard was only ever interested in entertaining his audience (and making money) and that meant writing good plays; but in writing good, entertaining plays, he somehow, almost miraculously, managed to create art works that, although obviously artificial (full of magic, witches, soothsayers, clowns, dreams), provide a connection to reality that allows the reader to feel that his or her life is being lived in illusion. When we watch Othello murder Desdemona or Lear cause his daughter’s death, we see some aspect of our own life – our failure to trust others, to communicate our feelings to people who matter and so on. We see the way the world works. So I would say the role of art in restoring our connection to nature is the same as its role in establishing its connection to art.

I also agree that one measure of the value of art consists in its capacity to inspire or spawn more art. But I suspect that this measure of value becomes at least problematic in the conditions under which modernism was born, mainly because concepts like “style” and even “influence” are problematic as they were not problematic in the past. I sort of know what it means for a painter to be influenced by the style of, say, Courbet or Ingres or Cezanne. But then something happens. What would it mean to be “influenced” by the “style” of Jackson Pollock, other than to create lousy copies or parodies of paintings by Pollock? Why is that? I am not sure what it means but one thing it DOES NOT mean is that Pollock’s pictures lack value. (The same can be said of Louis and pretty much any modernist master.) Does it not have something to do with the fact that Pollock’s way of making paintings cannot be considered a “style” at all? The idea of Style seems to assume that there is a way of doing something and different possible styles of getting it done. But in modernism there is no established “way of doing something” – no authoritative tradition or set of conventions that tell us what makes a painting or a piece of sculpture. Thus, Pollock was forced to make a new way – e.g., by using drawing in ways that did not outline three dimensional objects in an illusory deep space. The overall line in Pollock’s paintings of the ’40s and ’50s does not establish a style, but rather a medium of painting. And it seems like the idea of “influence” goes down the drain along with “style”. It’s not so much a method or technique that inspires as it is a conception or vision, so that using Pollock’s methods would be to create copies of Pollock paintings. Does this get at the idea that Louis and Pollock are not useful for painters following them in history?

LikeLiked by 1 person

“In Northrop Frye’s book on Shakespeare called A Natural Perspective, I read that the Bard was only ever interested in entertaining his audience (and making money) and that meant writing good plays; but in writing good, entertaining plays, he somehow, almost miraculously, managed to create art works that, although obviously artificial (full of magic, witches, soothsayers, clowns, dreams), provide a connection to reality that allows the reader to feel that his or her life is being lived in illusion.”

Well put Carl. I was in a bit of a rush before and what I said about the need or otherwise to re-establish our connection to nature came out rather wrong. I think what I really meant is somewhat contained in the above quotation from your comment. Obviously a connection to nature is what I would want to feel, and what I think I do get from so much art that fascinates me. Perhaps what I was getting at was that this might come about by way of something not incidental, but almost ‘miraculous’, as a result of trying to resolve tensions between all sorts of nitty gritty stuff right there in front of you, be it paint and canvas, neckties and bird wings, witches and soothsayers, and perhaps with all sorts of motivations fighting for attention, sometimes financial, sometimes personal and modest, maybe sometimes quite grand. The reality in Cezanne, or Shakespeare or Moby Dick, comes about through this collection and resolving of details. The story of a hunt for a whale means nothing to me without the clam chowder or sleeping with a cannibal who sells heads on a Sunday.

So yes, fill art full of nature, and then the art will enrich life. But what I am wary of is when that ambition is given too much primacy over the form and the resolving of details within it. That is when you end up with overblown junk like John Martin. And I DO NOT think that Pollock or Louis made overblown junk. I think the pictures DO have value. But sometimes I detect, in the absence of detail, a rush to declare their pictures representative of some deeper phenomenon within nature and ourselves. This is why I admire Alan’s writing. He has a genuine talent for communicating thoughts on what is occurring within the form itself and why that might be revelatory or of some consequence for art. It is very helpful. As is your last paragraph on what is happening in Pollock, and why that might be a dead-end for painters who attempt to follow that. I will think more on it.

LikeLike

I can’t see that Pollock ( or Louis) is working outside of convention.

There is paint, there is canvas, there is an oblong frame, there is harmonious colour, there is rhythm, there is mostly an exquisitely balanced composition – some of Pollock’s smaller works at the RA reminded me of nothing so much as of William Morris.

I cannot agree with Carl’s narrative of there suddenly being no conventions left in art. I see a loosening of conventions, a questioning of conventions, an experimenting with new ways of interpreting conventions, but nowhere do I see the wholesale abandonment of conventions, nor even the abandonment of a majority of conventions.

To my mind the success of Pollock’s large drip paintings has much to do with his being an exceptionally good painter in a very conventional sense. If convention-breaking in itself was such a big deal we would all be standing open-mouthed in front of Lucio Fontana.

Again, I don’t think it is the convention-breaking, revolutionary quality of Pollock or Louis that makes them stand alone without influence. It is because their processes (relatively speaking) exclude any individuality that style and influence are sent “down the drain”. Even they themselves had to move on rather quickly, having optimized the stupendous but unvarying effect that these processes

could achieve.

There’s nothing to speak against art whose effect is “like viewing a striking natural phenomenon”. But art can do more.

What was Hofmann’s reply to Pollock’s “I am nature!”?

“Then you will be doomed to repeat yourself”.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Without wanting to score debating points , I agree almost entirely with Robin’s last comment,of 16th, and very well put , but you can’t just slide off Rauschenberg at that point. Does he manifest any of the sterling qualities you describe of great painting, or even half decent painting? No he doesn’t . He does the old dark and light thing, but scatters it arbitrarily in unrelated patches across the panels to no organising purpose, in emulation of the William Burroughs trick of cutting up a narrative and reassembling it to provoke accidents of meaning.

LikeLike

OK, one more comment about Rauschenberg. Compared to Cézanne, Poussin, even Monet, he’s a total chancer. I’d still rather look at his “Combines” than quite a lot of stuff by some of the Ab-Exers and post-painterlies etc.

I await justification from Carl of his Twitter claim that the totally brown-all-over Louis is a masterpiece. Surely, Alan, you find that one “viscerally repellent”?

AND, my wife likes the “Combines” even more than I do.

LikeLike

And in terms of comparisons, why not put up Picasso’s Women at their Toilette(cartoon for a tapestry) 1938 Musee Picasso Paris, and compare it with Ace.

LikeLike

https://twitter.com/Emyr_Williams/status/810151090490671104

LikeLiked by 1 person

ACE!

LikeLike

The Cezanne is looking a bit squidged. And Alan is just a mark on the floor. A shadow of his former self. Probably because the Picasso looks like a bad wallpaper job.

LikeLike

How do you post pictures in Abcrit comments?

LikeLike

First you have to wire me $1000.

Then, the way I’m doing it is tweeting a pic, then right clicking on the pic, copy image location, paste into comment. Seems to work best for low res stuff.

LikeLike

…but it may work just by pasting in the location of the original image. Dunno really. Try something.

LikeLike

Check’s in the mail, Robin.

LikeLike

Well Emyr has used an enhanced image of Ace, brightening up the white areas, and the colour , while using a weak image of the Picasso. Good fun though.

LikeLike

Emyr is of course part of a fiendish plot, bankroled by the CIA, to prove you wrong on all occasions. This dastardly scheme will stop at nothing, even photoshopping weaknesses into Picassos that are not really there. You might think it’s fun at the moment, but just you wait…

LikeLiked by 2 people

[just to explain – Tim is still having trouble getting Abcrit in Sri Lanka and i’m relaying articles and comments to him by email, so he’s a bit off the pace, but very keen to participate. The following is two comments – Robin]

Re Rauchenberg :

I have always thought Rauchenberg an incredibly ‘arty’ artist. Along with JasperJohns and a few others in America in the fifties, he manged to do for American art exactly what the Europeans were trying so hard to escape from; a sort of superficial glamour that was if not trivial, at most artificial.

I am not surprised that he admired De Kooning, He (De Kooning) was the most ‘European’ of the American school, wirh a patness that was often uninspired.

Not being a painter I am unqualified to comment on the technicalities of paint application and so on, but I venture to suggest that Rauchenberg ‘moved’ into ‘object making’ to be a part of his ‘originality’ as a result of not really knowing what to do with his paint, or, rather, knowing far too well. A wheeze previously infamous as a Duchamp original.

Whatever the faults of American Abstract Expressionist art and its various practitioner’s styles and methods; it must be said that the ‘art informel’ typified by Rauchenberg did not lead the way forward into a new visual world and no amount of ‘sculptural’ bits and pieces will amend that.

Carl Kandutsch makes a good point, “…it’s a point about the difference between literal objects and works of art…” and David Sweet raises the hoary old fifties debates on ‘objets trouves’ (and their use in art):

“…such items are subject to dynamic formal processes. A necktie is a necktie, but its placement in the composition has been considered,and it makes a contribution to the variety of elements in the painting…”

But does it, however much “cosideration” there is ? Picasso and Braque had the advantage of huge talent and originality (in their use of’ ‘collage’), Picasso going on to actually ‘invent’ a constructional mode for, and in, his sculpture. It is interesting that, at the time, Matisse steered well clear of any such involvement in HIS sculpture. There is certainly no inkling of interest in the idea that the real world of ‘literal’ things could add anything to the compositional or expressive whole (let alone in his painting).

The trouble is that, on the whole, with very rare exceptions, a ‘necktie’ remains a ‘necktie; our perceptions and familiarity with the real world are so intense that it is extremely hard for an artist to alter them; on the whole they don’t.

This, of course, in my view, is the trouble with the Rauchenbergs; however much we may WANT to be convinced by the oddity of the inclusions of ‘things’ into his compositions, you are always left with the feeling that “well….so what, would there really be that much difference without them ?” Indeed, why not add a few more and we could expand the ‘space’ of the picture ad infinitum. (and of course that is exactly what ‘Conceptualism’ has achieved (if that is the right word !); in fact it has gone further than Rauchenberg and dispensed with the painting part altogether and left us with a world of totally banal and totally uninspired ‘objects’. As for the comment concerning the use of multiple canvases to create a ‘wall’ of pictorial space,; is that so original in terms of the huge numbers of historical triptychs and other mutli scenic pictorial ensembles /

For myself I find that the whole issue of ‘objects’ inclusion or otherwise in painting becomes a far more serious problem for sculptors. They have to battle constantly with the ‘reality’ of what they do; of the facts of existence in a real world of real things; of the business of isolating and making apparent the differences between ‘sculpture’ (as thing) and the physical world and all that that includes. Sculpture only ‘speaks’ to us (other than through mimetic representation) if it challenges our ability to recognise it as an ‘other’ ‘thing’; in its structural differentiation, in the differentiation of its spatial characteristics, in the differentiation of its physicality.

Incorporating recognition as a deliberate aesthetic device, as is inevitable with the inclusion of ‘real’ things, thus only exacerbates an existing fraught situation. The attempt by Duchamp and what follows to annul this fact by totally confusing the issue in kind, only serves to make it more apparent and starkly obvious.

To return to Rauchenberg, it is clear, in terms of the above analysis, that ‘devises’ are no substitute for a genuine rethink of painterly structural purpose, spatial purpose and that of colour, So I , for one. cannot agree with Carl that there is “still more mileage in the way Rauchenberg painted than in the way Morris Louis painted” .Louis, whatever the debate over methods and techniques, in my view introduced a whole new visual world which I had not previously experienced. What more can you ask for ?

LikeLike

“So I , for one. cannot agree with Carl that there is “still more mileage in the way Rauchenberg painted than in the way Morris Louis painted””

For the record, that was Robin’s comment, not mine. I believe exactly the opposite.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hilarious how an artist that not one contributor here has sworn any particular allegiance to (several works at most), can generate this much dispute.

LikeLiked by 2 people

From Tim Scott’s comment: ” in fact it has gone further than Rauchenberg and dispensed with the painting part altogether and left us with a world of totally banal and totally uninspired ‘objects’.”

This sentence describes how I felt viewing a small show of Andy Warhol’s pictures about a year ago. When I decide to go and look at art, I always try to prepare myself mentally beforehand by psychologically detaching myself from the ordinary experience of objects. (I try to see a coffee cup as something other than a thing used to sip coffee, for example.) Viewing the pictures actually managed to bring me back to earth so to speak rather than the opposite. With a few exceptions (silkscreens of electric chairs, which at least seem to communicate something), they seemed more not less like ordinary things I encounter in daily life. I left feeling deflated and depressed rather than exhilarated. Theories can say whatever they wish, but the experience of art remains what it always was.

LikeLike

I admire you commitment to looking at abstract art, and the seriousness of your approach. Each to his own, when it comes down to the experience of it. I guess trying to make it is a very different matter.

LikeLike

Here is a tweaked version. (please remove the other one?) Hope it’s an improvement. I think I’ve started something, but its making me anxious. Anyway, Rauschenburg’s work does seem to have a streak of nihilism running through it and much of the work still has a ‘student’ level mannered irreverant quality. As critics have seldom if ever ‘gone through the motions’ in a studio, they are not fully geared to get under the skin of art in my opinion (worse still they would resent any real artists telling them otherwise) – many can be quite rabid in their unshakeable regard of the visual… hence this show is a smash.

It’s funny how bravado dissipates to chic melancholy with the passing of time. It could have been the fact it was a lovely mild December evening, the hour was late and the gallery sparse, for I actually quite enjoyed wandering around the show and just let it wash over me. The late works in the last room had some pleasing passages of colour in them too – here he was finally taking on board the challenge of dealing with the transtions between sections (albeit on the same single expanse), decisions of whether to let an image bleed in or butt up to another in direct matter of fact ways, without any recourse to gimmick- I enjoyed seeing these. The light bulb combine does have a really good middle with terrific ‘in the moment’ paint handling. There’s a Frank Bowling in the ‘Recent Aquisitions’ room which puts things firmly in their place though; it’s a lesson in how to build pressure in the layering of dense closely hued and toned colours , from one of our finest artists. This work exposes Rauschenburg’s lack of real commitment to the problems of painting. He seemed happier to eschew these problems in favour of a more sugar-rush insouciant approach – a ‘naughtiness’ if you will. Art is bigger than the individual, though not here – which tells you the level of art achieved.

There is an early latex white multi-panelled work which was part of the collaboration with Cage and Cunningham. It set up the rest of the show (not by design) as it is a backdrop to something. That was what dawned on me in these über-trendy spaces. The work feels like a backdrop. Indeed a lot of work I see has that vibe – a museum readiness. It dissolves into the fabric of these kinds of spaces, in much the same way as one of Rauschenberg’s transfer prints – lovely little bits of nothingness – fade into the solvent stained paper. Alan makes a really intriguing comparison with the Picasso whose big fractured work still has an inventive coherence to it that is not there in the Rauschenburg. Working on big scales is very demanding (he would know more than most and clearly can spot it when things are not really happening). The visual stamina needed is exposed as lacking in “Ace”. It needed to be taken around the block a few times, rather than down to the diner and back. Many of the other works with the signature screen prints are immediate, slick and sexy with Popish references: a spaceman, weightlifters , JFK…”blown away, what else do I have to say”. Where they once jumped , now it’s more of a trip (probably literally to some) Picasso is much more athletic. Cézanne is positively Olympian and still hugely important for me and getting more so. The forces in Cézanne tumble dry you. Everything is visceral, visual and you feel every coloured brushstroke, building outwards. Work in this show closes inwards. Objects have a tendency to age badly, coloured cardboard and graphic design as art seems jaded now – if you remember seeing it back in the day, you couldn’t have seen it… back in the day.