Katherine Gili: Looking for the Physical was at Felix and Spear, Ealing, London, 10th November – 13th December 2016.

http://www.felixandspear.com/katherine-gili

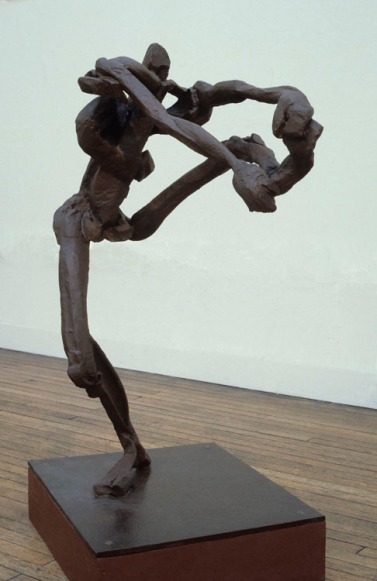

The sculptural power of Leonide, 1981-82, as it thrusts into space, to go no further back in Gili’s oeuvre, is clear affirmation that sculpture whose aim is to engage one immediately in a spatial way rather than having a predominant viewing point, does not need to do so equally from all points on the compass. Considered as an analogue for a structure, (with its figurative connotations in abeyance for the moment) its “stance” is forthright and unambiguous. It has remarkable physical presence from wherever it is viewed. It IS – it exists as an object in space, articulate and articulated, self-assertive and self-justifying (though that’s not all that it is). Each element is clearly defined in character and in its structural role. And it seems to say something about Gili herself, an enduring strength of character and artistic identity, proving that the unconscious reveals itself more through arduous realisation and reflection, than through perceptual self-trickery or doodling. It makes Giacometti for instance look very feeble indeed.

The fact that its structure is also a representation, if at some remove, of a body in movement allows one to accept without demur that it is anchored to a base and cantilevered from there.

When it comes to free-standing non-figurative sculpture, however, the question of “stance” becomes more problematic. And there is a danger that the pursuit of full three-dimensionality “in the round” can lead to the Giambologna syndrome – a spiralling contraposto that moves upward or around a centre and can only be terminated by some sort of top-knot or flourish. On first exposure to Gili’s Angouleme 2006-09, I felt that it suffered in this way, spiralling upwards from a tripodal connection to the ground, but on further acquaintance I became reconciled that this is not the case. What it does do structurally is to build upwards, twisting and turning in ways too complex to describe here, to establish a platform which serves as a launchpad to the next level, the next spiral movement. I found its complexity disarming and challenging, but it now seems abundantly clear, and still challenging, to one who is more au fait with the ambitions behind it than most viewers are likely to be.

Sculptures which aim for three-dimensionality with this degree of complexity on a large scale can threaten to become a kind of tangle. One somehow wants to see them broken open or pulled out into space more, as occurs in some of Gili’s earlier works, such as Sprite, 1989-91, and Serrata, 1994, so that there is not such a continuous flow and connection, part to part, throughout. Vervent III, with the range and variety of steel elements it uses, breaks the rhythm by introducing foreign elements into the structure ( I would love to see an expanded version of Vervent I and III); and yet to do so threatens to create potentially insurmountable structural problems on this larger scale, literally as well as sculpturally. And these problems are not hers alone, but are raised with varying degrees of success by all the sculptors who may be in pursuit of three-dimensional and spatial richness.

When a potentially free-standing sculpture is in a state of flux while under construction, it can be brought together to coalesce “up in the air”, by means of gantries, chains etc; it exists in open space. But there comes a point when these hanging parts are connected together, and it is then that junctions become crucial. The points of connection may be disguised by being spread or shared (this is how Angouleme works), but in the end it has to convince as a viable structure, however unlike other structures in the world it has become. And the old “magic glue” of welding will not convince, especially if a heavy weight of steel is made to cantilever improbably, putting undue strain on that weld, and in turn on other elements within the work. That is why Gili has evolved a complex web of connections spiralling up through the work.

It comes as something of a relief to be faced with these smaller and more modest works. They are part of a continuous chain of forged and torch-cut steel sculptures which began with Aspen, 1985-88, and includes such major successes as Volante, 1998; Vervent 1; 1998, Vervent II, 1999; Flow Free, 2005; Daedal, 2009; Vervent III, 2010; and Episodes, 2010.

Llobregat, in this exhibition, for me, distils the essence of sculpture. Its forged, hammered and torch-cut steel elements have assumed the permanence, the durability one meets in ancient artefacts in bronze or wrought iron. Each steel piece is taut, elastic or cursive, physically compelling, absolutely right in scale, the right note, the right length in the right place. Nothing is overstretched or over-torsioned (not always the case in Gili’s work). And one feels behind its cursive movements through space the weight of experience of how such movements are possible in the real world. And what I like so much in these small sculptures is the expressive force of the steel, as steel, with all the further associations that each formal element brings to the lyrical vitality of each sculpture. The modesty of scale in these small sculptures brings the steel factor even more fully to the fore.

It is as if the steel has become hardened through use and acquired the patina of long serving functional objects, functionless though they may be. Each element has a role in the structure of the sculpture which it fulfils with economy and expressive force. Of how many sculptures today can this be said?

It is perfectly possible to hold two contradictory views on the role of steel, or any material, and still to act – the one that it has unique properties that stimulate the imagination of the sculptor, whose sensibility is thus wedded to the material whose properties determine what is physically possible; and the other, that sculptural inspiration comes first, and steel is just a suitable vehicle for their expression. Both are no doubt in play here, but it seems to me that these small sculptures have the power that they have because the former persuasion is dominant, and without Gili getting inside the malleable properties of steel, as it were, in her way of working, they would not quite have the delicacy or the expressive range that they have.

It should go without saying that these properties of steel have to be projected into it, arising from the sculptor’s imagination, but there is no material more suited to the kind of plasticity sought here than steel, ductile, malleable, potentially tensile when tempered by the artist. It is like the issue of timbre, Klangfarbe in music; not just pitches and intervals, but the unique resonance of each instrument which colours the motif and projects it in the aural imagination of the listener.

But beside this hard, durable character in Gili’s art, there is a lyrical side. In the development of Gili’s sculpture since the late 1970s there is both a continuity and a dividing line between works which are clearly studies of anatomical movement, and works in which the sculpture has acquired an independent life, a sculptural plasticity, and the elements have been subsumed into this willed plasticity. There is a point at which the demands of the sculpture as sculpture have taken over, and the elements out of which it is built have begun to take on pressures which are to do with resolving the work as sculpture, and not to represent anything outside it. Although direct engagement with the body has receded since the 1980s, what has carried over into this independence from representation are ways of working the steel to draw out of it it’s full plastic potential – extruded elements which take on a three-dimensional life in relation to others in the work and contribute to its overall character as a sculpture, independently of naturalistic forms. There may be an inherent habitual tendency in perceivers to try to read figuration or representation into them, but there is nothing in the most achieved sculptures that would warrant such an interpretation.

However, this does not mean that they are totally non-representational. Plasticity implies that the “movement” represented through the matter of the sculpture as it turns through literal space is more than its literal movement. It implies greater movement, greater “force and counterforce” than is physically, and literally presented. There is therefore an element of illusionism present in all sculpture that is not just a technical demonstration or a mute object.

Quinary (shown at top of page), in this exhibition, a compressed version of the earlier Angouleme, is the sculpture that raises these issues the most. It is a companion piece to a number of other smaller sculptures of recent date, of varying success. The largest sculpture Gili presented at Flowers Central Gallery in 2015, Meril, 2014, seemed to me complex but successful. If I have a criticism of the works on this scale, such as Quaternary, shown at the R.A. last summer, it is that there can be an undue thickening out and twisting of some elements, which acquire a somewhat heavy character, which is answered by or echoed by counter torsions in an over-complex roundalay. Some elements with multiple twists along their length appear to have a load-bearing function that they seem ill-equipped to handle, and this can lead to doubts about the structural logic, or viability of the sculpture as a whole. There is a tension between the actual physical structure and the plastic and spatial structure, and it is not always clearly overcome. I’d like to see them break out of this in some way. This at least was my reaction in front of the sculpture, but the more I look at the photographs of it from different angles, the less these criticisms seem to hold up. I don’t know quite what that says about the sculpture, or about me.

However Quinary does not raise such doubts to anything like the same degree. It arises more as a problem in larger sculptures which approach waist or head-height. Again I repeat, these are problems that are not confined to Gili’s sculptures alone, but are common to the work of others who broadly share her concerns, with allowance for all due differences.

In Quinary there is no feeling that the structural weight is being carried by welds, for instance, or that it is borne hazardously in ways that cast doubt on its credibility as a total “organism”, so successfully is the integration of multi-directional sculptural forms which carry upwards through the piece. Without describing it in detail, a mammoth task, consider one element in the lower centre of the work, the bent wishbone-like form which seguays into a quite different mini-structural element at an oblique angle to it, which in turn supports an upper movement convincingly, i.e. sculpturally, not literally. That “wishbone” form is itself supported by two pincer movements from elements of quite different character, and so on. That I refer to it as wishbone-like does not imply that it is derived from organic form, but just that it is necessary to use some form of simile in order to identify it from other forms in the work. And the simile is much less evident in front of the work than it is in photographs.

This transformation of material in the service of plasticity has become increasingly sophisticated in Gili’s art, from the likes of Llobregat, Bold, 1988, and Sprite, 1989-91. It has become an evolved language of form. However on a larger scale the tendency for the working of the steel to invoke naturalistic form can be distracting. But it is easy, though misconceived, for detractors to characterise this work as “figurative”. The problem for many viewers is that they are not used, and not prepared, to invest enough time to really examine what is going on in these highly concentrated and complex works, which require a certain empathy from the observer if they are to be grasped at all. Quaternary, shown at the Royal Academy last summer, was difficult, though rewarding. The question of the accessibility and visibility of all movement within the sculpture is answered in the affirmative by Quinary.

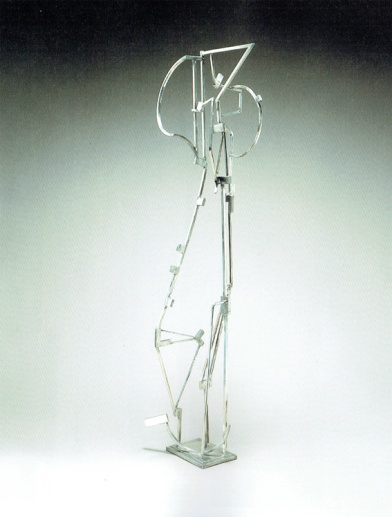

Naiant is reminiscent of some of Tim Scott’s small sculptures and should be compared with them in some future exhibition, or in the Musee Imaginaire we are all obliged to live in due to the desuetude of contemporary curatorial attitudes and gallery fixations. It equals them in the variety of its worked steel components and the fluid “language” created from them. Scott’s Moment of Rhythm, 1989, or Feminine for Structure I, 1986, would make interesting comparisons, though I am not for a moment implying that the one derives from the other. Gili is on a trajectory of her own, and has been for a long time. (A Musee Imaginaire that would include Rodin’s Crouching Woman, Leonide , Anthony Smart’s First Figure 1981-82, Tim Scott’s Adele VIII, 1994, and go on to include the more recent and more “abstract” works of these and other sculptors of the same persuasion.)

Tim Scott, “Feminine for Structure I”, 1986, steel, H.41cm. © Tim Scott, photo courtesy Galerie von Wentzel, ColognePotsdam

Tim Scott, “Moment of Rhythm”, 1989, steel, H.55cm. © Tim Scott, photo courtesy Galerie von Wentzel, ColognePotsdam

There is no need to analyse the smaller sculptures shown here. They are the felicitous, relaxed and playful offspring of harder won works like Llobregat and Flow Free. Mulled, Quicksap, and Turnsole are simply pure sculpture of a very high order, ampler volumetrically and spatially than they look in reproduction. Each one is a little gem of pure sculptural invention. Mulled is closest in feeling to some of Scott’s smallest table works. And analysing or describing them would not make them any more amenable to the insensitive. It would be like trying to explain a melody, albeit a complex one with many feints and turns.

Naiant beats Caro’s table pieces on their own ground, being terser and less decorative, less to do with placement, more interactive in the physical pressure of part on part, and exploiting the expressive properties of steel, as moulded in the artist’s sensibility through her direct making.

Anyone who sees figuration in Quicksap deserves a slap on the wrist. After all, to eliminate all reference to things or structures in the world of the senses, even if it were possible, would leave one with something very arid indeed from a sculptural point of view, like a model of some scientific postulate (behind appearances), or a systems diagram.

This is where a sculpture like David Smith’s Tower Eight, 1957, shown recently at the R.A., scores, albeit with a minimal “physicality”. Although it resembles nothing in nature, its structure is transparent, lucid, if crazy, fully available to sight. We know that it is literally held together by welds, but its structure as sculpture seems entirely plausible, self justifying. One does not question its means of support, so dispersed throughout the work are its points of junction. Irrational, yet amenable to reason, one does not need to use the word “pictorial ” to define it. Within its very narrow range of physicality and three-dimensionality, it none-the-less points the way to a possible resolution of the issues faced by the ambitious among today’s sculptors. Blackburn, Song of an Irish Blacksmith, 1949-50, in the same exhibition, has a richer plasticity and inventiveness with steel. How “pictorial” is it, and by what means is its pictorialism established? – by distancing of parts and abrupt changes of scale relative to one another, establishing a greater visual distance than the literal space between them. Welded to a base these sculptures may be, but this gives them a freedom to operate that totally free-standing sculpture struggles with. Which brings us back to Leonide again. Although one has to say that the eloquent and rich plasticity of the likes of Llobregat, Vervent III, Mulled, Quicksap and Turnsole, and the range of formal elements they employ, are of a physicality and three-dimensionality beyond anything achieved by Smith, or Caro, for that matter – really sculptural, in short.

And there are other sculptures from the past careers of Scott, Smart and Gili herself, pre-Leonide, that are worth another look in this context, but that would be to take one too far away from this modest but intriguing exhibition.

Postscript: it should be said that as well as the sculptors already mentioned, Robert Persey, Mark Skilton and Robin Greenwood, to name only the steel sculptors, are engaged with many of these and related issues right now. Who knows what the future will hold? Skilton in particular seems to have evolved a bold and expansive style out of the way of building employed by Gili in her early Towards Aspen, 1984, though it is doubtful that there is a conscious link there.

Good that Abcrit has published Alan’s serious, lucid, and analytical critical appraisal of SCULPTURE(s); (Katharine Gili’s show). But why only Alan ? Are there not other commentators out there who love sculpture and appreciate the complexities and battles that ambitious sculptors have to deal with; and what about sculptors themselves ? there cannot only be the ex St Martin’s group who have something to say; the ‘Brancaster’ type of discussions have of course been amply covered; but they are of a type, spontaneous opinion and value judgement that cannot have been, by their nature, considered and mulled over in time; what one goes to Abcrit for, in fact.

Let us have some commentary on some of the issues in sculpture that Alan raises (and has raised before); not that I am remotely suggesting that they can be predicted or resolved on paper; only the actual sculpture can do that; (we know that anyway), but it IS possible for insights in art to come directly from the mind (and eyes)

LikeLike

I agree, Tim. Hope there will be more comments. Gili’s work isn’t easy to talk about–though it’s great, and Alan has opened a bunch of doors. I’m struggling to say something. Takes a while to get at least some of the idiocy out of my writing. Will “post” shortly. Running off to class now.

LikeLike

Considered as an analogue for a structure…” There’s the rub.

“Each element is clearly defined in character and in its structural role.” There’s another one.

“…sculpture whose aim is to engage one immediately in a spatial way rather than having a predominant viewing point, does not need to do so equally from all points on the compass.”

Needless to say, you can’t legitimately apply any of these phrases to abstract sculpture, in my opinion. OK, so here they are applied to the overtly figurative “Leonide”, a sculpture I like a good deal – in fact it was my favourite work in the show by Gili at Poussin Gallery in 2011. It’s one of the most spatial figurative sculptures by anyone, but the problems of making figurative sculpture even more spatial are one of the contributing factors in my desire, and that of others, to make sculpture more abstract, because it’s so difficult to get out of the continuous return to the torso/pelvis centre, and escape the symmetry/frontality of the body, no matter how far you stretch out. “Leonide” certainly does get out a long way for a figure, but in the end not far enough, not spatial enough, not free enough of constraints, which are, by the way, far, far more confining in figurative sculpture than they are in figurative painting.

And also by the way, “…sculpture whose aim is to engage one immediately in a spatial way” is very similar to my Madrid show (with Gili, Persey and Smart) catalogue commentary, 1988, writing of Degas’ “Dancer looking at the sole of her right foot”, (Rewald XLV): “This object engages you immediately in a spacial [sic] way, it is intrinsically interesting because of the spaces it generates.” As I’ve stated before on Abcrit, Degas best sculpture seems to me to be really striving for and achieving not only physicality, but also a significant degree of spatiality, as in proper three-dimensional articulation, NOT totally obsessed with HOW it stands, but getting away from the ground in order to engage with some other sculptural content in space – albeit with very little room to manoeuvre within and around the figure/body. Degas contribution to this is greater than any previous figurative sculpture, Rodin very much included. I think that’s why, for me, Degas still counts in a way Rodin does not. But even Degas is really peripheral now to ways of advancing abstract sculpture. It’s a whole other thing from his thing. But at least he had the wherewithal to see that sculpture must be as fully three-dimensional as it can be, unlike Smith.

The constraints which Degas was compelled to work within because of the subject of the figure are absolutely on a continuum with the constraints of working three-dimensionally “from all points of the compass”. If you are going to move from body-based sculpture towards genuinely abstract sculpture, as a number of sculptors who were involved with “Sculpture from the Body” in the eighties now have (and continue on that path, without end in sight), then I don’t think you can countenance a part-measure of either spatiality, physicality, or full-on, all-points, top-to-bottom three-dimensionality. Any compromise or falling away on any of those three counts, such as the thing only being three-dimensional in one orientation (which, if you think about it, makes no sense anyway), or being physical without being spatial (if that is possible), or vice-versa, will likely be the result of some kind of figurative idea, or alternatively, will result in such an outcome. The question, as it has been for a while with Gili’s work, is: is it figurative? If so, does Gili then accept the limitations of sculptural figuration? “Leonide” is undoubtedly figurative. I personally think all the sculpture illustrated in this essay, with the possible exception of “Naiant”, but including the work by David Smith (not sure about the Tim Scotts), are, by degrees, figurative, though they differ in the way in which they are figurative.

At the risk of getting my wrist slapped, and indeed to risk this comment being seen as an attack on one particular individual, Gili’s sculptures seem to fall into two kinds of figuration, both of which have their particular limitations. I’d better get out of the way here that, yes, of course, my own work has limitations too, etc. etc… But that’s for another day. The first kind of figuration of Gili’s work reminds me a lot of the “feet” sculptures that students of “Sculpture from the Body” did in the early eighties:

“Mulled”, “Quicksap”, Turnsole”, “Episodes” and “Vervent III” all fall into this category of small works that have three contacts with the ground, each of which behaves slightly differently, in a manner analogous to how the three (somewhat diagrammatic) points of contact of a foot assume different roles as they absorb different movements of the body they support, and so demonstrate different physical tensions or other properties. All well and good. And then there is an upward-moving part that approximates to the lower leg. So within that “set-up” you can have all the differing expressive variations, and how those four or so parts interact with each other as they stand together on a surface; but what you can never do is actually address very much else, in terms of the content of the work. Therein is the limitation – the sculpture can only really speak of its very own particular and very limited responses to being an object under the influence of gravity, albeit a reactive or organic object. As I have written extensively before on Abcrit in an argument with Alan about Tim’s “Song for Chile” about why I think structural determinism in sculpture is in itself a completely figurative idea, and therefore limiting and intolerable in the pursuit of abstract sculpture, I don’t propose to set it all out again unless I have to. Obviously, comments like “Each element is clearly defined in character and in its structural role” and “Considered as an analogue for a structure…” apply to “Leonide” without question, but if they still apply to this further group of works, Alan is outside his rights to describe them as abstract. That may or may not matter to Gili, I don’t know. It matters to me.

The second category of work is also reminiscent of early work from “Sculpture from the Body”, but this time reminding me of works which dealt with the “core” of the body rather than an extremity.

Into this category I would put “Quinary”, “Meril” and “Quarternary” and others. This group of works has more scope – there are more things going on, with a little more room for them to happen. At the same time, it seems much less clear what they are up to. Less clear, even, than these early torsos and pelvises, where the parts more directly followed the comings and goings of muscular and skeletal organisations. So we are left with a kind of musing or mulling around or riffing on semi-bodily structures, using the very physical language of forging, a speculative creativity that at least appears to have a degree of freedom to come and go in different ways, over and above the first group of work. It’s not without its pleasures, and Gili does it well, but it never goes far out of its own orbit. These sculptures are not, and perhaps don’t aspire to be, spatial. And paradoxically, compared to the other group, they have something of a problem with how they stand, or rather “sit”, on the ground – as indeed did the early torsos/pelvises. The interrelated but fragmentary nature of their content, characterised by a singular “knot” of activity, a “roundalay”, to use Alan’s word, from which parts attempt to escape, but then return (as per figurative sculpture), means that they do not easily “address” the space around them, or the floor… or the viewer.

“…these problems are not hers alone, but are raised with varying degrees of success by all the sculptors who may be in pursuit of three-dimensional and spatial richness.” Yes indeed, but the title of the show is “Looking for the Physical”. That to me is a particular but partial answer, just as the sculptures themselves seem to be particular but partial – on the one hand you have work that deals, almost to the exclusion of anything else, with how it stands – and indeed, without putting that “stance” under any great stress or tension by extension, cantilever, off-balance elements, etc., so that in effect the variations on this theme are somewhat aesthetic. On the other hand is work that engages in some internal comings and goings, but really struggles to stand in the world, and to my way of seeing, certainly does not “engage one immediately in a spatial way”.

The other thing to say about my comparisons is that the “Body” stuff is 35 years old. Things have to move on. Things have moved on. I think Alan acknowledges the problems in the work to some degree, particularly with Gili’s larger works. Fair enough, but I have to say I never thought I’d see Alan write this kind of thing:

“Llobregat, in this exhibition, for me, distils the essence of sculpture. Its forged, hammered and torch-cut steel elements have assumed the permanence, the durability one meets in ancient artefacts in bronze or wrought iron.” … “The modesty of scale in these small sculptures brings the steel factor even more fully to the fore. It is as if the steel has become hardened through use and acquired the patina of long serving functional objects.”

All of which is to be resisted by abstract sculptors now, I would have thought. And nobody, not even Alan Gouk, knows what the hell the “essence of sculpture” is.

Forging has its own problems for abstract sculpture-making. It’s all very well to imbue steel with plasticity, but if you are assembling a sculpture out of forged parts, that plasticity does not necessarily or easily transfer to the sculpture itself and how it is organised. If you are then going to slot into a configuration of some sort (there we go again, back to figuration) a string or group of heavily forged parts, already loaded with very specific but small-scale pushes and pulls, then it becomes very difficult to manage the plastic properties of the whole sculpture and be able to freely and spontaneously push and pull the whole thing around. It is, I would suggest, well nigh impossible to make such a construction properly spatial or three-dimensional. Such is my contention, though I would be the first to admit that simply stopping forging (as I did in the late eighties) does not solve these problems of getting to grips with the totality of the work as a plastic, spatial, three-dimensional, fully abstract sculpture.

And then we have: “After all, to eliminate all reference to things or structures in the world of the senses, even if it were possible, would leave one with something very arid indeed from a sculptural point of view, like a model of some scientific postulate (behind appearances), or a systems diagram.” No way is that true. And then, bizarrely, Alan has the temerity to postulate that a very boring and feeble diagrammatic symbolic figurative piece by Smith (Tower Eight) is “a possible resolution of the issues faced by the ambitious among today’s sculptors”. This is a bit fatuous, to say the least. How would Alan feel, I wonder, if I suggested that the problems he and other abstract painters have (and yes, even Alan has problems, like we all do) might be solved by paying attention to (let’s say, for example, plucked from the air) how “The Seer”, 1950, by Adolph Gottlieb, is organised: (http://www.phillipscollection.org/research/american_art/artwork/Gottlieb-The_Seer+.htm).

After all, “…its structure is transparent, lucid, if crazy, fully available to sight…”. Why not go down that route, Alan, and stop all this crashing about with big paint-laden gestures, getting yourself all in a mess?

Apart from the detail in some of his early work, this is possibly Smith’s best effort at full-scale three-dimensionality:

And it’s a shocker. There is nothing in Smith to be taken forward.

Gili is quite within her rights to pursue figurative or semi-figurative sculpture. Alan is not within his rights to claim it is abstract, or that it has bearing upon the sculptural pursuits of those attempting to make such work, or that it makes any kind of new contribution to those issues. It doesn’t. There is the suggestion sneaked into this essay, perhaps with a view to justifying Gili’s disguised figuration, that “illusionism” is inherently, happily and unavoidably figurative:

“However, this does not mean that they are totally non-representational. Plasticity implies that the “movement” represented through the matter of the sculpture as it turns through literal space is more than its literal movement. It implies greater movement, greater “force and counterforce” than is physically, and literally presented. There is therefore an element of illusionism present in all sculpture that is not just a technical demonstration or a mute object.”

Illusion is in fact the meat and drink of completely abstract sculpture. Happy New Year.

LikeLike

As I probably have said before, I have yet to see any sculpture that is not ” a configuration of some sort”. And I have suggested that the word configuration therefore best be dropped as a redundant way of characterising sculpture. Even so, configuration simply semantically does not imply “figurative” as used in art parlance or in fact. Throughout Robin’s comment there is this tendency to think that “structure” ie the way a construction exists and resists gravity, is “figurative” inevitably, whereas it is simply, as Shaun, to my great surprise, points out, a fact of physics. If abstract sculpture is to disobey the facts of physics, then it is a puzzle as to how it can “stand” at all. By trying to tie Gili’s work back to the early experiments “from the body”, and imply that she has not ” moved on”, Robin is simply showing prejudice against a sculpture with markedly different aims from his own.

It was the same with the discussion about Tim Scott’s Song for Chile II. Because it stretches out across space from point A to point B, ( sort of) this does not give it a ” configuration”, and because Tim has described Rodin’s Torso of Adele as a kind of arch, it does not follow that Song has the configuration of an arch, and even if it did, this would not make it therefore ” figurative”.

In parenthesis ….. When I introduced working “from the body” into projects for the Advanced course at St Martins in 1978, it was certainly not to revive figuration in sculpture. It was because so many of the students coming to the school in those years had no experience of making anything, besides strings of plastic bottles or piles of feathers. It was to give them a sense of the physical reality of things in the world. It came as a great surprise to me when these body experiments were taken up by members of staff, chiefly Tony Smart, Kathy Gili, Robin Greenwood, and Mark Skilton, amongst others. An even greater surprise followed when Smart wanted to introduce working from the skeleton. The subsequent sculptures developed far away from anything I could have envisaged. I have not always been happy with the outcomes, and this continues to this day, but I have supported the ambitions throughout. I too want an abstract sculpture, and a plastic and spatial sculpture that ” engages you immediately in a spatial way”, (R. Greenwood). But I do not want a monopoly on the ways and means of achieving it.

And I have not ” sneaked in ” any such suggestion that illusion in sculpture is inevitably ” figurative”. Illusionism simply means that something is being created that is more than the physical components of its constituent parts. That is all.

LikeLike

And by the way, Smith’s Tower Eight , and other of his “crazier ” works come near to disobeying the logic of “ordinary ponderable things”, ( that was left to Caro, allegedly) but they do not disobey the laws of physics. Being attached to a base and employing “magic glue” (even in silver) does give them a certain freedom and a certain illusionism which free -standing sculpture must surely envy, but you wouldn’t want to go back to that, would you? There is indeed the rub. To read figuration into it is an option, but unnecessary. Not always the case in his work, obviously, but that gives it an open ended quality that I for one see as a positive, even now.

LikeLike

The interesting thing about Gili’s development is that Towards Aspen 1984 did not turn into the sorts of thing Mark Skilton is doing, but into Aspen 1985-88, which shows the sort of condensation of sensation that she is after, and which Llobregat so magisterially demonstrates. (as described above).

LikeLike

A work of art is always a representation of something, even if it is only the confused state of mind of the person who conceived it, or in rare cases, the serenity of complete command of the resources of the medium and of the artists feeling.

Even such supposedly “abstract” works as Bach’s The Art of Fugue are built on the mastery of rhythms and harmonic tensions that have their origins in mimetic rhythms, word paintings, symbolic statements of liturgical meanings, depictions of evil, the fall, murky Lutheran stuff, such as repeatedly occur in the Cantatas, tumbling rhythms, representings of a sea of emotion, tension and relaxation, heart beats, regular and irregular. Not so much “figurative” as physically enacted.

When the last unfinished fugue comes to an abrupt end (whatever the reason for the missing page) we are left hanging, mentally confused as the build up and flow of the musical argument is cut off, coitus interruptus ; we are unable to complete it (no-one is) because what we have experienced is not just an edifice of logic, but a logic of feeling the outcome of which only Bach can supply. So a work of art can be representational without being “figurative” in any sense of that word. And the same is true of sculpture.

LikeLike

I think you’re rather stretching a point beyond endurance there. I know of nothing more abstract than Bach’s Toccatas.

As too, with the business about the Physics. Whilst it’s true that everything in the known universe obeys those Laws (barring the odd black hole; and assuming we are in the world of Einsteinian, or even Newtonian Physics, perhaps), well so what? My sculpture, your painting, a chair obeys those Laws. (My sculpture stands up just fine, despite being made of tinsel and fairy lights.)That does not mean that the content of the sculpture must be anything to do with a demonstration of those Laws. And what I have repeatedly said is that sculpture needs to address other things, over and above the literalness of how it stands up. I’m sure you agree with this really.

So too with the business of configuration – yes, every sculpture can be said to have a configuration, depending upon how you define that word. But again, if the content is about the “stance”, the configuration will be to the fore. Think about those Degas sculptures again and you’ll see. It may be a matter of degree, but the more abstract a sculpture can be, the more it will sideline or mask its configuration in favour of something else.

In any case, the search to make things more abstract is a bit of a challenge to the orthodoxies of common sense, rather along the lines of what is happening at the cutting edge of High Energy Physics. Or so my wife says.

LikeLike

Walls,bridges,legs,tripods,platforms,barley twists,clusters,boundedness,horizontality,pictoriality,

objectness ,architecture,reliefs, literalness,organic, gesture, figuration, and figure/body referencing etc etc.

These are just some of the long list of things that have been the bane of the new sculpture over the last 40 years.All the sculptors I know know all this.

The world of the new sculpture has turned and commentators shuffling these negatives will get us nowhere useful.

The door forward is wide open. New exciting things are happening though not always easy to spot. The things on the list will never be settled they can surely though now be left to the individual and the commentators will have the choice as they always have had to look back check the “list” damn the work without proper explanation or step over the line baggage at the door and see what they see without others eyes and prejudice .A new unstuffy and non academic approach is needed now which asks questions of which the answers are not so obvious but that could play the part for this to keep moving forward.

OK so less words will be written. Good.

LikeLike

Why have the photos of the “feet” and the paper studies “from the body” been removed?

LikeLike

It is an amusing coincidence that while this discussion is going on, all this week Radio 3 has been featuring the work of the Second Viennese school, with many parallels with the question of how abstract is abstract. It would appear that Schoenberg’s most successful works, by his own admission were those in which events from his own biographical fate formed the emotional core and even the dramatic content of the work. In the String Trio, for instance, he dramatises in sound the experience of a heart attack and the injection straight into his heart which saved his life. Similarly his Violin Concerto is biographical in character.(his favourite composition). The sustained anger of the Three Satires is fuelled by the critical abuse he had been receiving, and fury at the fashionable propagandising of the other neo-classicists.

Anton Webern would on the face of it appear to be the most “abstract” of the group, and yet his Variations for Piano sounds (if I may be mischievous) not unlike a table-tennis match between unevenly matched partners, and in one movement by two players attempting the game for the first time, unable quite to keep the ball on the table.

So, I repeat, to make something that has no structural connection to anything in the perceivable world is indeed a rather arid prospect. And these composers do not even have the issue of gravity to contend with, as they “breathe the air of another planet”.

LikeLike

Presently speaking it is not wether the piece of work references to the perceivable world but that the piece create a perceivable world of its own wherein the structural relationships are perceivable on their own terms without outside reference.

It is real.

LikeLike

The thing about the “feet” is …… Would we know or guess that they were feet if we hadn’t been alerted to the fact that they were so based ?.

LikeLike

The reason the Toccatas, the Art of Fugue and the Cello Suites have such an appeal for sculptors (and painters) is because the dancing, climbing and tumbling rhythms are physically enacted, simultaneously physical and auditory, as the physical/structural in sculpture is simultaneously visual, hopefully. The velocity of attack and the strongly accented structural element is as near to a physical enactment, ( literally for the performer) as music can give. How important are these qualities in the more physical world of abstract sculpture (and painting)? Very, I’d say.

At the opening of Contrapunctus 9 the attack is propelled like a bullet from a gun, and the propulsive motor rhythm is maintained throughout, which is why jazzers love Bach.

At the closing pages of Contrapunctus 11, there is a pile up of harmonic clashes and crescendos that is almost visceral in effect. No 13 has danceable pizzicato dotted rhythms, foot tappers.

Vyacheslav Gryazonov on YouTube has had a go at completing the last one, unconvincingly. It’s really a coda rather than a culmination, but at least it’s better than a computer would come up with.

But enough from me!!

LikeLike

I have tried, unsuccessfully, to write about my sense that these jazz performances by the second Miles Davis quintet strike me as, on the one hand, highly abstract, and on the other, very visual, corresponding to modernist painting and sculpture at around the same time (mid-60s). To my ear, they provide some intuitive support for your remarks on Bach (“…the dancing, climbing and tumbling rhythms are physically enacted, simultaneously physical and auditory, as the physical/structural in sculpture is simultaneously visual…”) –

All composed by Wayne Shorter

LikeLike

Yes, it is semantics again. My own reading of ‘configuration’. (at any rate as far as sculpture is concerned), would be a collection of parts organised to make a whole and the effect that produces. I agree with Alan that this has nothing to do with ‘figuration’ despite the word root. I would be perfectly happy to abandon its use for sculpture.

Coming to ‘structure’, yes of course its physical role (obeying the laws of physics) is cardinal and immutable.I too cannot see that any structure could be (in this world at any rate) without these facts (scientific) of existence. However, I do use the word loosely in sculpture to also mean a creative ‘AIM’ as well as literal support, connection, elevation against gravity etc. For sculpture to succeed it has to enter a world of made intentions that are more than what is ‘known’, from previous experience or practical laws.A sculptural structure has to be as much the outcome of intuitive feeling, invention and (let’s face it) inspiration, as the handling and construction of materials in space and ‘subject to gravity’. None of this implies or supposes ‘figuration’.In fact I would say that there is no difference applying the above to either figurative or abstract sculpture; the only qualification being how ‘good’ it ends up being ultimately.

Not having been able to see Gili’s show it would be invidious of me to enter into the discussion of individual pieces; but I would like to bring up a quotation from Alan’s original essay (as it happens Robin picked out the same paragraph). “….Plasticity implies that the ” movement” represented through the matter of the sculpture as it turns through literal space is more than its literal movement. It implies greater movement, greater “force and counterforce” than is physically and literally presented. There is therefore an element of illusionism present in all sculpture….”

This is precisely what I mean by ‘sculptural’ structure; it IMPLIES more than it presents in its actual form. I hesitate to use the word ‘illusion’ which smacks of trickery; but I see what Alan means Sculptural structure has to be ‘developed’ from actual structure; it has to simulate the liveness of an inspired underlying idea about physical form as well as exist in its literal construction; to become a ‘poem’ in the actuality of its physical decisions. Yes, it ‘represents’ something, usually many things (in the mind of the artist), Spectators have to arrive at heir own conclusions Incidentally, I wonder what J.S. Bach would have to say about being called ‘abstract’ ? Or Degas for that matter?

I agree that orthodoxy is the death knell of advancing the scope and nature of what abstract sculpture can attempt to do. I have seen some small Inca clay sculptures (Jaime Coaque) that knock the spots off us for ‘abstraction’ !

LikeLike

So great to have Giacometti welcomed to Abcrit!

I bet there were times of the day when Giacometti might have agreed that beside Katherine Gili’s sculpture his looked feeble. I expect more often than not, though, he would have been incensed by the suggestion. I’ve heard at least some of Picasso’s sculpture pissed Giacometti off. At an opening for one of Picasso’s shows Giacometti told Picasso that a specific piece simply wasn’t sculpture—one of Picasso’s still life sculptures I think it was. (Didn’t Caro early on make some Picasso-esque still life sculptures? I seem to remember a vase of flowers in bronze.) (Back in the ‘70s George Spaventa, a great, Giacometti-esque, Studio School sculptor/teacher, told Lee Tribe that what Lee was doing simply wasn’t sculpture.) Giacometti left Picasso’s opening disgusted, and went to some brothel or other. When Giacometti got back to his studio/home at 5 in the morning, Picasso was there waiting for him. Picasso wanted to know why his sculpture wasn’t sculpture—and he thought Giacometti could tell him.

Giacometti’s sculptures (many anyway) are physically/literally fragile/feeble. Bruce Gagnier’s are by and large more robust (more robust than Giacometti’s, more robust than Gili’s), but Bruce has made very, very fragile/flimsy sculptures. People sometimes respond to Bruce’s figure paintings and drawings by saying Bruce can’t do arms: Bruce’s arms are often, in his drawings and paintings, fragile/feeble (in his sculpture his arms are often as far from feeble as you can get)—but at the same time they have a kind of steely strength. Giacometti’s “line” in his drawings—in his sculptures and paintings too—is often very steely.

Where am I going with this? I’m not sure, but maybe this is an opportunity to open things up some, to get out of the good guys vs bad guys box, the figure sculpture vs “abstract” sculpture trap.

Also it’s an opportunity to suggest that to be “feeble” is not all bad. Yves Bonnefoy, the late, great, French poet (and author of a 10,000 page book on Giacometti (I’ve read it cover to cover at least twice)), talks about his “desire to confront our world in those aspects that are most fleeting, that seem least charged with being, and to give sacred meaning to them so that I might be saved with them.” Xmas decorations, “tinsel and fairy lights” might be taken seriously, Bonnefoy seems to suggest.

I should and shall say I think Katherine Gili’s sculpture is great—and Alan’s writing about it is great too. I should also say I’ve never seen Gili’s sculpture except in reproductions. And I don’t really know (or care too much) what “great” means. I just have lots of questions—I guess because I find the sculpture—and the writing—so exciting. I have questions: I don’t have answers.

Besides Giacometti, isn’t there, in a strange kind of way, a lot of Ancient Greece in Gili’s sculpture—and in the sculpture of many of the other sculptors Alan refers to—even in Alan’s writing?

It would be silly to suggest that Plato—not Roger Fry, not Clement Greenberg—invented Formalism. But what is physicality? What is spatiality? Ideas? Platonic “forms”? What is the essence of sculpture? There is some kind of “philosophy” behind this kind of “thinking.” And it’s something more than just NOT—decisively or hopelessly vaguely—“Existentialism.”

Here’s Yves Bonnefoy again, this time writing about a Byzantine church, but touching on Ancient Greece (his (Bonnefoy’s) Ancient Greece anyway) too:

“But nothing can replace the most majestic of the paintings (The Dormition of the Virgin, c. 1260. Church of the Trinity, Sopocani, Serbia). And when one turns toward it, in the October light, it is the true speech, so long sought after, that all at once resounds. How close he is to us, the man-god offered in this room that hereafter will remain empty! And in how pure a way he brings together, following the deepest wishes of our hearts, the two discordant intuitions of Western thought: what perishes—and is our fate—and what is eternal! There is the beautiful and pensive face, grave as though wounded in the light of the nimbus, and yet all around him the army of this conqueror of the world is deployed—weapons, clouds, the clarified powers of what is human—and thus are effaced those excessive simplifications in which the dialectical ambitions of the Western mind have so often come close to ruin. The god of Sopocani does not mutilate. He is not that Apollo of the Hellenistic sixth century who, in all the brilliance of his force, remains like the unswerving trunk of a tree, like some pure and blind form of plant life, so strongly did Greece want to identify humanity with life, with its impersonal forms and with its harmonies, unaware of that other realm which is the finite existence of the human person who is conscious of himself.”

In Tony Smart’s most recent Brancaster, Helga Joergens-Lendrum suggested there was something “organic” (I think that was her word) about Tony’s new sculptures. Helga was immediately dismissed from the Brancaster, tortured, and then shot. I think Helga was taken to be asking does the sculpture look like this or that kind of plant—but maybe she was sensing a plant-like “life”/vitality, a plant-like lack of awareness of death in Tony’s sculpture. Maybe there’s an animal-like lack of awareness of death in some of Mark Skilton’s sculptures. Alan seems to have picked up his infectious enthusiasm for “ancient artefacts [often based on animals] in bronze and wrought iron” from David Smith.

But what about Gili’s sculpture? The title of her show was “Looking for the Physical.” Bonnefoy: “Accordingly, the finest statues of the Hellenic period seem steeped in the flow of nature: the eyes half-open, half-closed like those of animals, the mind, free of all aims, worries, or concern for the future, free to participate in an unbroken inner communion with the eternal. Who of us is not fascinated by this physical time in which the pulse of the timeless seems perceptible in human gestures, like sap universally present in each plant? Death seems dissolved in nature; and the human image, which is elsewhere scattered or incomplete or inaccessible, seems mysteriously whole. This is the secret need of great anthropomorphic art.”

Bonnefoy goes on: “If the true nature of the human being is to be encompassed in an image of physical presence and find complete expression within the limits of this form, and in spatial terms, it is a precondition that our inner sense of the human should be experienced as an essence; it must be free from that inner abyss, that sense of division and fracture which accompanies the aberrant and troubled temporality, aspiring to transcend its limits but incapable of reaching outside itself, to which the early centuries of Christianity made a decisive contribution.”

Gili’s work is very “physical.” Alan is great at describing this “physicality”—but he doesn’t really ask what it means. The “physicality” is anti-Giacometti, anti-“spiritual”—maybe anti-“modern” in different ways. Gili’s work is unsettled. It’s challenging, as Alan says, very challenging.

If Tim Scott’s sculpture had eyes, they’d be “half-open, half-closed like those of animals”—Classical animals! Gili’s a Romantic. The eyes of her sculptures are wide open.

Alan writes very intelligently about stance and movement and gravity in Gili’s work. He helpfully spots a “wishbone-like form” in Quinary—and then is very careful about underlining that all he’s saying is the form is just wishbone-like—it’s not derived from organic form, etc. I’m very comfortable saying I see a lot of Paul Taylor, the great American choreographer, in Gili’s work. I have no idea whether or not Gili has ever seen the Taylor company dance. I do know she’s had some serious contact with dancers though. A modern dancer has a very different sense of gravity from a ballet dancer. I can’t describe the differences with any real authority. I can say I’ve seen modern dancers walk into a studio and just joyfully slap their bare feet on the floor. Everybody knows ballet dancers never touch the ground. And this little bit of knowledge adds to my experience of Gili’s work. It doesn’t violate its “abstract” purity. And I can go a little further and say there’s a sense of strain in Taylor’s lifts that’s close to the sense of strain in Gili’s Angouleme or her Serrata. Again, Gili’s work—and Taylor’s work—and my life, my experience—it’s all richer because of this association.

Merce Cunningham is another great American choreographer. He’s thought to be a super “abstract” guy—but he wasn’t “abstract” enough to make dances without dancers, without “figures.” And he kind of never said, No. He did once that I know of. He’d asked Richard Serra to design a set for a dance. A tilted floor was part of Serra’s set. The dancers would have ended up either crippled or dead after performing. Merce said, No. But otherwise he let just about everything into his work. There’s a lot to learn from choreographers.

“Isn’t that right?—what you’re really imitating in human bodies is the frame drawn up or down, compressed and expanded by their posture, by the tensed and relaxed parts, and that is how you edge closer and more believably toward their reality.” That was Xenophon, not Bonnefoy. Bonnefoy’s isn’t the only take there is on Ancient Greek sculpture. Gertrud Kantorowicz had her own take. She quotes Xenophon at the beginning of her wonderful little book, The Inner Nature of Greek Art. The book is kind of all about contrapposto, Alan’s favorite topic. I should quote the whole book now, but I’ll just mention there’s lots of talk about “in-the-body movement,” “in-the-body laws,” etc. in her book—lots to interest “Body” sculptors. Xenophon wrote his Memorabila about 2,500 years ago. Things have NOT moved on.

Alan didn’t mention the drawings in Gili’s show—in the online catalog anyway. I get the feeling drawing was never a thing at St. Martins. I think the drawings are terrific. I think it’s great that Gili showed them. I don’t know why she showed them, but I kind of see them as a special challenge for Robin. Not long ago Robin stuck some great hands and fists in his sculpture. Gili might be trying to get Robin to take his hands seriously.

Gili’s work is full of challenges. I don’t think the Museum of Modern Art is up for her challenges, but maybe one day they’ll put Angouleme out in their sculpture garden. It’d look great beside Rodin’s Balzac. We’d be able to ask, which is more feeble? And we’d ask what’s the other side, the “contrapposto,” of feebleness? We’d learn something about life—good students that we are.

LikeLike

I wrote this in 2010:

“…looking back into history, figurative painters… only had to open the door and step outside their studios to see a whole world of particular and varied possibilities – to say nothing of all the human stories and dramas with which to populate their worlds. What do abstract artists have? It looks dolefully meagre by comparison, and initially discouraging of any aspirations to match in abstract art the plastic and spatial achievements of the greatest figurative painting. Yet, though it may be difficult to see how such ambitious desires can be fulfilled, it is only in the deepest darkest mystery of such difficulty that one might find the freedom to invent something truly original. It is in that very void that the promise lies, the outrageous possibility of working towards an abstract painting [or sculpture] without an idea or a conceit or any other kind of false agency, free from all constraining configuration. I know it invites ridicule in the current climate of literalism to suggest that the artist might work without ideas or concepts of what the work will be “about”, might shed all pre-conceived formats or images (even “abstract” ones) for the finished work – but I stand by it. This freedom, this openness, this desire for discovery, is the key to unlocking the big, wide-open spaces of new abstract art…”

And from a slightly earlier essay:

“The business of making complex abstract painting or sculpture now… is a long way removed from the spontaneous abandon and carefree self-expression which constituted the popular myth about being an abstract artist in the second half of the 20th century. That idea still has romantic appeal, but it will no longer suffice to produce progressive results. Having tip-toed all around the edges of abstract art, we now have to plumb its depths. Our modern abyss which we must face up to is the amorphous and vast complexity of possibilities, the endless potential, of empty abstract space… We must enter the abyss…”

As I said to Emyr the other day, if you know what you are doing, you’re not making abstract art. If you are not engaging with the black hole that is in front of you all the time, then you are probably “representing” something or other. I recall a rather telling moment in my studio, perhaps six or seven years ago, when in the rather dark despair of being unable for a long time to finish work or be satisfied with anything that was happening (which seemed to last years), I chanced upon a part in a sculpture that stood out from the rest; it looked strong and clear and very physical. For an hour or so I was elated, only to soon realise that the power of the form resided in its resemblance to a human arm and hand. Once I’d seen that, I was completely flummoxed – and back facing the black hole. Was it true, I wondered, (and I wondered for a long time) that content in sculpture just HAD to be some kind of figurative metaphor from the literal world in order to gain any kind of reality?

A very similar occasion arose a couple of years back in Mark Skilton’s studio when we were discussing a supporting part that held up a large weight under compression and all sorts of other forces. Did it look like the hind leg of an animal? Is that how it worked? Was it a metaphorical leg, an analogous physical structure, an artful and abstracted demonstration of the laws of physics?

It’s real easy to fall away from what is real, to fall back into figuration in all its guises; making properly abstract work is really hard, and it’s a work in progress, but it is possible. Take a look now at the best of last year’s sculpture in Brancaster – say Tony Smart’s “Sidney Series No.9,”, Mark Skilton’s “Brian the Boa Constrictor” and my “Habia Rubica”. See if you can identify in any of them a metaphorical content based upon a structure from the literal world (Jock, you’re not allowed to do this, you can see anything in anything!). I think you would be hard pressed also to identify a configuration, at least in terms of how I define the word. This is more than semantics. There has been over the last few years a sea-change in sculpture and how it operates. For example, Tony has described his work as a “spatial continuum”. That’s an excellent approach. That is progress. It’s not the only way, of course, but there is no analogy involved, no relation to literal structure, no identifiable structure from the real world at all, and most definitely no metaphors. Not even a poetic one. Lots of abstract illusion, though. In abstract art, nothing is “represented”. Tim, Alan and of course Jock do not seem able to recognise this.

By the way, I think Alan’s description of “Llobregat” is pretty good, and I agree with it (apart from the “essence of sculpture” thing), more or less, and I quite like the sculpture, always did – but it is a work that is very reliant on figurative allusion and suggestion, not to mention its shared properties with figurative sculpture of the past. Comments suggest that the differentiation between abstract and figurative is not too important. I think otherwise. It really is.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Another view of Llobregat and Angouleme

LikeLike

I’m sure it is very hard to make abstract sculpture—but, Robin, you must admit: it’s 10 times harder to write about it. It’s essentially impossible for me. I sincerely apologize for the pain and suffering my “sentences” must cause.

Katherine Gili seems to be quite relaxed about words, specifically the words “abstract” and “no.” Maybe that’s why I like her work so much. There’s a kind of fullness to her work that’s not constrained by words/ideas—or, it seems to me, “the subject of the figure.” Robin, you see old classroom assignments—the “feet” sculptures, the “core” sculptures—limiting Gili’s work. I think I understand what you’re talking about. I see that kind of thing happening at the Studio School a lot when students are given “assignments.” Students complete assignments—they do what the teacher tells them to do—but they don’t begin to make sculpture, to project “themselves” (or some “other,” or space between themselves and an other) into the work. What seems to me to be the marvelous thing about the Sculpture from the Body project is that that kind of thing (the “assignment” thing) seems (to me (from reproductions)) NOT to have happened at all.

I’ve been looking at one of the drawings of Achille Emperaire that Cezanne made as studies for that great early portrait of Emperaire. The drawing’s great—especially great for a guy we’re told couldn’t draw. You might say the drawing’s “figurative”—limited by what Emperaire looked like, even by what Cezanne thought a drawing should look like (at the time maybe he thought drawings should look like drawings made by Rubens). I might agree that the drawing’s “figurative” (I’m trying to be as relaxed about words as Katherine Gili is)—but I’d say there’s an “abstract” dimension to the drawing (the way the “form” is handled, the way the “space” is handled) that is FULL of Cezanne. How crazy am I to see some of Cezanne’s drawing in Gili’s sculpture?

LikeLike

I certainly don’t want to imply that Gili is doing basic classroom exercises, because hers are in many ways very sophisticated sculptures. In fact, I don’t imply any criticism, other than to note the similarity to certain things done in the past, which is why, I think, that Alan is able to write about them in the way that he does – somewhat conventionally.

As I recall, there are two very contrasting drawings by Cezanne of Achille Emperaire, both brilliant in very different ways. Cezanne is undoubtedly a master of drawing as well as painting, and he does, like all great artists, point the way forward to the inevitability of an art that is wholly abstract. That might make you even more crazy than you are.

LikeLike

Musical analysts are forever talking about the “structure” of say a sonata first movement by Beethoven, without in the least suggesting that it is based on a structure from the literal world. The very notion of “structure” in this context is an acknowledgement of the abstract nature of the music, (even allowing for the representational connotations I’ve mentioned in Bach). And this is the way Tim is correctly using and defining the word in relation to sculpture. Sculptural structure and literal physical structure are not co-terminus. I think we all agree on that. But this does not mean that a sculpture can convince by stretching its physical structure to the point of total implausibility, because this will be detected by observers even if they are unable to pinpoint why they are uneasy.

Tower Eight by Smith, and Tower 1 is an even better example, meets all your criteria for a structure that has no metaphorical content and is not a literal demonstration of the laws of physics. Indeed these works are crazily free of all that, and yet you seem to be unable to grant them the property of opening up possibilities for the sort of abstraction you require, (allowing for their minimal three-Dimensionality of course). Marry them up with John Panting’s surviving sculpture in New Zealand, and further possibilities open up, perhaps. But this is taking us far away from Gili’s sculpture.

I would also take issue with your use of “metaphorical” liberally applied to any work in which the steel parts lose their literal identity as pieces . Does a spanner become metaphorical because it suggests the possibility of torsion? Does a forged bow shape become “metaphorical” because it implies forces not literally present?

LikeLike

Again I’d say — would we think that those “feet” we’re figurative if we hadn’t been alerted to the fact that they were based on feet?

LikeLike

Also, there’s an anomaly here with your views on painting. When I say that figurative painting and abstraction are on a continuum but with a clear dividing line which cannot be crossed with impunity, and give reasons and examples (Matisse’s Moroccans being borderline, Hofmann’s Pre-Dawn just making it over to abstraction), you read figuration into it and yet still refer us to Cezanne and Constable for the missing ingredient.

Whereas in sculpture you say that they can have no truck with one another, are on totally divergent paths, never the twain shall meet, “figuration” tainting the very possibility of abstraction, even though you all got to where you presently are by way of an engagement with the structural element in key figurative sculptures of the past. Can someone please square that circle for us?

LikeLike

Which is not to say that I don’t admire the ambition for a radical abstraction such as you seek.

LikeLike

Ah! Well, there’s bound to be a few contradictions knocking about, but I would say, confirmed by a few mutual friends, that, good though they are, your articles and comments on the whole contain more than mine, not to mention the odd volte-face.

I don’t look to Cezanne and Constable etc. for any “ingredients”, but as examples of high visual ambition achieved. Like we all do. I don’t look to Smith for that. There is absolutely no getting around the fact, no matter what you say, that Smith is not three-dimensional. Nor, in fact, is he spatial. Why would I want to be influenced by him? Allow for his minimal three-dimensionality? No way. Give. Him. Up.

I do think – perhaps we agree on this – that painting appears to be more of a continuum, but there are big differences in sculpture. Spatiality is one very big difference, as I have comprehensively explained above. I’d also say I’m not at all sure that painting should be quite the continuum that it is. When’s the revolution?

I don’t think Tim does use the term “structure” correctly, because both you and he relate it closely with “standing” in the world, albeit a “poetic” interpretation of that standing. Whereas, I don’t think we know that much about abstract sculpture to really say. We have yet to find out what “structure” really means in abstract sculpture, if it is indeed even relevant in the terms we currently understand it. For me, the jury is out on that. Like I say, we are staring into a hole, and we don’t know the answers. We’re all about asking the questions at the moment, and if as a sculptor you are not doing that, you’re probably out of it. Sculpture from the Body solved nothing, that just asked questions too. I think that the way both you and Tim write about sculpture sounds rather like you do know the answers.

LikeLike

Don’t be silly. How could I , non-sculptor, possibly know the answers to your questions as a practicing sculptor. All I do is respond to what I see in front of me as best I can. But I do not take the messianic revolutionary tone, and I think you are greatly exaggerating the “abyss” that confronts the abstract sculptor. I bring in musical analogies only to try to show that ” total abstraction” is something of a myth. As Tim says — how do you think Bach would respond to his music being designated abstract? And how do you think Cezanne would have responded to the comment that ” his painting …. points the way to the inevitability of total abstraction”. I hear shades of Clement Greenberg in that, or am I just being mischievous again?

LikeLike

“How could I, non-sculptor, possibly know the answers to your questions as a practicing sculptor.”

Indeed, but if you think you know what is the “essence of sculpture”, there is no telling what you are capable of writing. Or was it just the essence of figurative sculpture?

I never, ever talk about “total abstraction” – what would that mean? Starting from a figurative source, but getting rid of it completely? Hmm. I only talk about making things more abstract. I’m sure Bach would agree.

LikeLike

Plus you’ve told us twice now that we should be looking at Smith’s “Towers” for a way forward.

LikeLike

Just glanced through my book of paintings. I don’t think there is a single one that could be termed totally abstract. It has never been a priority of mine, for good or ill. Whenever any kind of animation, implied movement, optical or physical, creeps into a work of art, as it inevitably must if one is after a vibrant and substantial art, there occurs a rhyming with happenings in the real world, like it or not, and there’s no need to call this metaphorical. It is a physical fact of human activity. Get -over-it!

LikeLike

So, when is the revolution?

LikeLike

Actually, I can’t let you off that easily. Are you saying that any kind of movement is figurative? What is this rhyming thing? Creeping in? Blimey.

(And this, note, shortly after: “Which is not to say that I don’t admire the ambition for a radical abstraction such as you seek.”)

LikeLike

Tony Smart’s “Sidney Series No.9,”, Mark Skilton’s “Brian the Boa Constrictor” and my “Habia Rubica”. Lots and lots of movement. Figurative? Semi-figurative? Just a bit figurative? Content based upon a structure from the literal world?

LikeLike

Here another contradiction: “Musical analysts are forever talking about the “structure” of say a sonata first movement by Beethoven, without in the least suggesting that it is based on a structure from the literal world.” So it’s abstract? When they talk about the structure in music, that is surely talking about movement… and it’s abstract. Yes? No?

LikeLike

“Whenever any kind of animation, implied movement, optical or physical, creeps into a work of art, as it inevitably must if one is after a vibrant and substantial art, there occurs a rhyming with happenings in the real world, like it or not, and there’s no need to call this metaphorical. It is a physical fact of human activity.”

Perhaps it would help to pin down the meaning of “animation” and “implied movement” by specifying that a painting (in order to amount to a painting in lieu of an object of some kind) must make sense; it must say something, and to say something, it must have a point. The “rhyming with happenings in the real world” would then consist in the fact that making a painting is a human action – something that a human being DOES. (If I ask a question, I am doing something – something other than making some noises or some marks on a piece of paper or computer screen; if I point out to you the road to Boston, I am doing more than raising my arm and extending my index finger, etc.)

The fact that a painting (like any other human action, including other kinds of human utterance) must make sense doesn’t mean that the painting is “figurative” or “metaphorical” in any way, although a non-abstract painting is (i.e., it makes sense by way of figuration or metaphor).

Abstract painting or sculpture is required when certain inherited ways of making sense (e.g., using physical materials like paint and canvas to represent things in the world) no longer produce things that are more than trivially paintings; they are no longer capable of satisfying the kind of intimate relationship to reality and to self that we crave from art. So then the artist is forced to explore – or more accurately, to discover for him- or herself – what it is that makes something a painting. But that is a personal and not a scientific question, as all human expression is personal rather than scientific.

LikeLike

I think we’ve done that point to death. So everything obeys the laws of physics. So do Alan’s paintings. They have to hang on a wall. Does he have to think about that?

How do you know, why should you care, and what is the point, of knowing what is the “first and foremost consideration in the sculptors mind.” Mind your own business – tell us specifically what you think of the three sculptures, given that you are only forming opinions from photographs.

LikeLike

No — when musical analysts point out , say, motivic relationships in a work , they are “abstracting” salient features from the matrix and tracing connections. This does not make the work itself abstract. I’ve tried to show that even the most apparently “abstract” of Bach’s works have a grounding in physical, bodily rhythms, dance rhythms, amongst other sources , and require an athleticism on the part of the performer that reflects these origins. And movement is only one of the elements separated out for analysis, and I’d say that rhythmic movement, ie sequential movement in time, is the least abstract element in music. Structural relationships could be described as a kind of movement at a stretch, but that is a different kind of movement.

When it comes to sculpture, movement has to be conjured out of stasis, by the constructed transition from one nexus of parts to another, and is therefore inherently illusionistic, in that these parts remain static in themselves. In a sense the perception of movement has to be projected into the work by observers. But this does not make the transition “figurative”. I repeat that I have never said that movement in any of these senses is inevitably “figurative”, in the sense that we use it in visual art.

LikeLike

I used to tend to think that paintings could be “wholly abstract” , ( although not an absolutist myself in practice) until one day Hans Keller the music analyst and critic, champion of Schoenberg and the 2nd Viennese School came into St. Martins and said that all art is a representation of something. He was using the word representation with its German connotation, ( as in Shopenhauer’s “The World as Will and Representation) I.e. A vision forming in the artist’s mind and projected, as if on a stage, into reality. Just as Schoenberg said that what mattered was the “musical idea”, and Rothko said that his paintings were a ” portrait of an idea”. ( the only quarrel with that is that the idea is something being groped towards rather than pre- existing). With that reservation, the sculptures under discussion are classically representational, in that what is being represented is the idea of a plastic and spatial three-dimensionality.

On the other hand what I for one abhor is a painting which begs to be seen as figurative by playing up illusionistic effects which encourage the viewer to “see things “in it, and talking about the epiphanal moments that sparked it, (Supply your own examples), when to all intents and purposes it is just a bumbling attempt at an ” abstract” picture.

LikeLike

Those are big reservations, no? We can’t make use of horrid things like “portrait of an idea” now, can we? And these semantic rigmaroles only have a point if they are useful.

As far as I am concerned, plastic and spatial three-dimensionality are the things being looked for, to be discovered. How would I represent them? For a start, I don’t know what they are until I make something that I might recognise has those qualities.

If I am not representing an idea or anything else, and it doesn’t by chance end up looking like something else, then as far as I am concerned, what I’m making is abstract. I don’t think that is a difficult definition, and all the stuff about rhyming and chiming are natural consequences of being human, and so imbuing the work with humanity. I don’t think we need to split any more hairs over this.

I have always railed against the idea of “pure” abstraction, which is anathema to my desire for abstract art of richness and complexity. And although the business of making something “wholly abstract” may well be an aim that is never quite fully realised, and may even be somewhat intellectually simplistic, it is a useful and coherent ambition which will (and is) resulting in original work.

LikeLike

We’re out of time sequence again. My “No–” was a reply to a question of Robin’s, not to Carl!

LikeLike

Wholly abstract –” pure” abstraction , totally abstract ? — if only these they were only semantic questions I say again. As so often on Abcrit we have moved ineluctably from the concrete to the theoretical/semantic, and when attempts are made to clarify , we have now moved to a utilitarian definition of theory, — only if it is useful?

On David Smith’s Towers, — if instead of being a vertical 23 feet high narrowly 3D work, Tower 1, (which I wouldn’t like to see in a high wind either) were turned horizontally, stretched out three dimensionally, and married to the sort of structuring in Panting’s space frame sculpture in New Zealand, it would satisfy all your requirements for a plastic and spatial three Dimensionality, would it not ? Or would it? But would it satisfy the Brancastrians? Probably not, because there are unspoken prohibitions in the Brancastrian mind-set that Gili seems to have fallen foul of.

LikeLike

There is no “Brancastrian mind-set”, evidenced by the many serious disagreements between individuals during the discussions. Indeed the fact that there is no single mind-set is one of its attractions.

LikeLike

Nonsense – the “Brancastrians” are an open-minded and mixed bunch.

LikeLike