The Shchukin Collection at Fondation Louis Vuitton, Paris has been extended to 5th March 2017.

http://www.fondationlouisvuitton.fr/en.html

This unmissable show is likely to be the highlight of this year and possibly of the decade. The flamboyant kite-like superstructure in Frank Gehry’s signature style apart, the main galleries display beautifully the visionary taste and judgement of this extraordinary Russian collector. What monstrosities may we expect when this show closes? Gerhard Richter? Cy Twombly? Bill Viola? Ai Wei Wei? God help us! So let us rejoice while we can that there once was a man of superlative judgement to take the true temperature of his times, a time before the psychopathology of art globalisation. This is an exhibition that normally would have gone to the Met. or the National Gallery. How many handbag sales have gone into this colossally expensive enterprise on the fringes of the Bois De Boulogne?

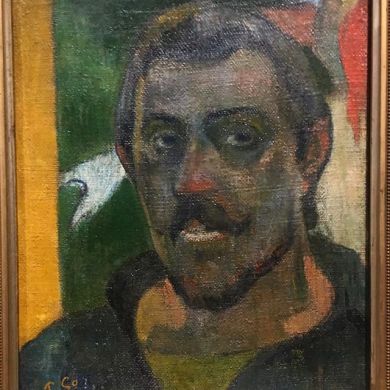

The first arresting picture is the little self-portrait by Gauguin on very coarse grained burlap, which holds its own beside a Cezanne self portrait. Due to the prominence of the tooth of the burlap Gauguin seems a ghostly eminence part pickled in aspic, but the conviction of his self-image shines out none-the-less, the Gauguin he wants us to believe in, and it is hard not to, despite all that we know of the reality.

Next is the marvellous small version of Monet’s Dejeuner Sur L’Herbe, the complete image of the much bigger original cut down fragment in the Musee D’Orsay. How startlingly fresh and unprecedentedly bold and direct is the firmness of the young Monet’s touch in delineating and placing of each element, dresses, clothing, tree-trunks, foliage, picnic, patches of light on the tablecloth, the dappling of light throughout, learning from Manet but at the same time surpassing him.

This is what was so apparent in the confrontations afforded here, however many times one may have seen some of these pictures in different contexts and settings; how solidly and succulently Monet, and Matisse (although justly lauded for the delicacy of his brushwork), apply their paint in the service of responding to the light-filled sensuousness of lived experience, besides which so many of the most vaunted masterpieces of modernism look like museum-bound pictures, already half tainted by art-out-of art fustiness, and a dingy minimalising of the full lustre of the sensory world. How over-rated in the end is cubism for instance, by which I mean the analytical cubism of Braque and Picasso, in comparison with the larger world of Matisse, and how uncomfortably slight are so many of Picasso’s early paintings, of the Blue and Pink periods, for instance, in comparison both with his models, Gauguin and Lautrec, and with Matisse over the same period, even allowing for the difference in their ages.

In my talk on the key paintings of the 20th century I said that it took ten years for Matisse to surpass the Demoiselles D’Avignon, with The Moroccans and Bathers by a River. But here is The Pink Studio of 1911, which already is a larger world, a larger conception of pictorial space, and a larger vision of the kinds of sensation that can be embraced in paint, and that painting can offer. It may seem perverse to describe Picasso’s world as smaller, in view of his profligacy and many-sidedness, but when it comes to pictorial architecture in which everything counts and nothing is superfluous or de trop, where “what to eliminate, what to amplify” is prime, I stand by this judgement. The picture is much bigger than one is led to expect, (71″ x 87″), looks even bigger, and it extrovertedly opens out to meet the space in front of it, despite the drawback of being heavily and unsuitably framed and under museum glass, in a way that Picasso never does. However inventive Picasso is in his greatest period, the proto-cubist years 1906-1908, and however powerfully plastic the representation of volumetric form in The Dryad (Nude in the Forest), which looms out hazardously, or Three Women, or the powerful presence of Woman with a Fan, 1908, (the first pre-cubist version), the figures seem to be enclosed in a veil of subterranean light, the light of a self-consciously murky gravitas. “Hermetic” is the correct word for the phase of analytical cubism represented here by Violin and Guitar, 1913. But who wants to live for long in the sensory deprivation of a dank cell.

Matisse’s early picture, The Bois de Boulogne, 1902 (he was then 32), irony of ironies, is indeed an impressive inaugural masterpiece, in dialogue with the Gauguin influenced The Luxembourg Gardens, 1901-02, hung near it. The Bois is highly original, without any obvious parentage, although more Manet than Monet. The colour is not impressionist; it is unique. Matisse as so often sees things afresh, whatever the influences may have been. It’s all “in the paint”, an arabesque of black linear pattern of tree branches and grey-green shading, with a contre-jour filtering of light through the trees, and just enough perspectival drawing to give modelled depth. How far it is from impressionist practices is revealed in the comparison with two superb late Pissarros of L’Avenue de L’Opera and Place Du Theatre, one fore-grounding two horse-drawn charabancs and trees, the other taking a view across the Place, and down the centred Boulevard Des Italiens.

Manet is the obvious precursor for Matisse’s Spanish Woman with Tambourine, 1909, though once again the influence is surpassed in the emboldened and simplified black line drawing which carves out the form of the head, hair and facial features, and on through the rest of the clothing. The paint is amazingly solid and glossy, especially the blacks, and on top of which the delicately shaded pink pattern on the bodice stands out as a master-stroke of improvised paint-wizardry. The whole painting is a meditation on Manet’s spontaneity of attack, which it rivals magnificently. Contrasted with Picasso’s 1909 cubist version of Woman with a Fan, the artful brittleness and clever complications of the Picasso, the play of light and shadow around the enclosure of the head, and on the cheeks, for instance, and the curiously effete twisting of the left hand, begin to reveal an artist more in thrall to artifice and ornamentation than to his former powerful dramatic directness.

The disarming frontality of The Pink Studio,1911, with its broad planes of lilac wall and pink floor, gives way to a more naturalistically naive space than its companions, The Red Studio, 1911, and Interior Still Life with Eggplants 1911-12 Grenoble, which seem to have evolved out of it. But it too contains a multitude of sly cross referencing between various aspects of his production, sculpture, drawing and painting. My guess is that it was in this version that he first saw and set down the possibilities of an interplay between a sculpture standing in for a physical human presence, and its reflection in drawings and paintings which ambiguously chart the fictive stages from object to illusion, or layers of illusion, and which he would then further complicate by introducing mirrors in which the image within is not rationally related to the objects mirrored.

The illusion of depth is created mostly by reducing the scale of the objects and pictures relative to one another, so that we imagine the paintings on the floor and back wall to be progressively further away from the plane of the picture itself.

Of the Cezanne’s, the Man Smoking Pipe (Leaning on a Table) is magnificent, and so too the Lady in Blue, 1900-04, which Matisse must surely have seen, if not on his visit to Shchukin in Russia, then sometime in Paris. But the late, heavily encrusted Mont St. Victoire takes the palm. Here Cezanne surely is creating a conscious chef d’oeuvre to stand through the ages as a monument to his vision and a lifetime of engagement with the mountain… Rock of ages! The lustrous paint seems to be inches thick (though it isn’t), more solid than glaze upon glaze, like some substance transcending paint, evoking mother of pearl or the inner coating of an oyster shell.

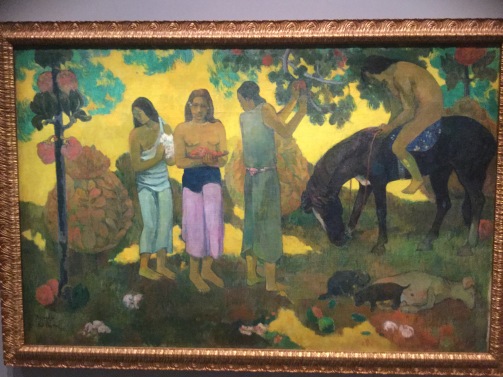

Matisse would also have seen the major Gauguins which Shchukin’s superlative eye had selected from his uneven production, and as John Golding has written: “It was Matisse more than any other artist who saw through to its ultimate conclusion the greatest lesson that Gauguin had to teach, that it was possible to be a decorative artist and still remain within the avant-garde, or more strongly and more appositely, that it was possible to be a decorative painter and still to be a high artist, even a revolutionary one”. (New York Review of Books, Jan. 1985).

How different this is from the words that David Sylvester put into the voice of a female friend in introducing Patrick Heron’s Tate retrospective in 1998, not having the courage to say it himself: “‘Decoration’ –I suppose that’s about the most damning thing you could say about a piece of art!” How far off the mark are so many of the celebrated authorities and pundits of modern art in England, then and now!

Matisse would go on to make even further use of the decorative elements in Gauguin’s Gathering Fruit , 1899, and Are You Jealous?, 1892, freeing up and at the same time integrating arabesque pattern and cursive drawing more fully into the plastic shaping of the whole image, as in La Desserte. Harmony in Red 1908-09.

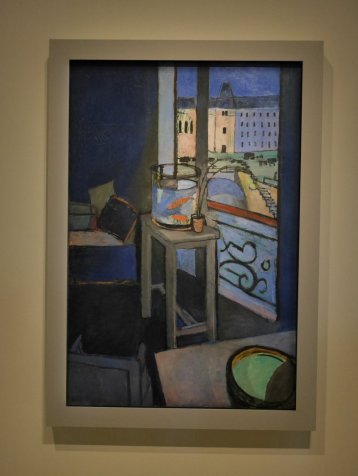

Interesting too to see an alternative version of Matisse’s Interior Quai St. Michel, with Goldfish Bowl 1914, remarkably similar to the one in the Musee D’Orsay.

One would still have to make the trip to St. Petersburg and Moscow to take in the full extent of Matisse’s amazing achievement in the years 1908 to 1912, even before the so-called Radical Years of 1913-1917, but there is enough here to confirm the judgement of so many true painters that he is the greatest painter of the 20th century by some margin.

Decorative as in not having a specific descriptive function which obeys acquired rules of construction (“compare European sculptures based upon the ‘muscle’ with African ones based upon the medium” Matisse paraphrased) Did Picasso ever escape this approach or rather moved to the extreme end of the same axis…? , not decorative as in not just a ‘streamlined’ arrangement of colour and pattern (Louis Valtat a minor example, though if you want to start a sword fight with anyone – compare with Derain?)- this is the notion of colours just existing in their own right with no “pressure” (witness recent discussions on Abcrit) , decorative as in a full synthesis of perceived – real, fluid- space translated into painted space -(absorbing and extending the lesson of Cézanne and NOT coming up with cubism which took his vernacular and returned it to point 1 – see above), not decorative as in a systematic synthetic formatting (which is where twentieth century modernism went). I think it’s such a complex word to explore and may well continue to be redefined. Matisse saw colour as a “force” and used colours which “collide” into one another, however his painting journey to get to the late 40s (for it was a wilfully investigative one) was delightfully meandering and lit up so many intriguing side roads (for so many others to wander down) Great article on a stupendous show.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I stand to be corrected by a proper art historian, but I believe The Matisse “Interior Quai St. Michel, with Goldfish Bowl” 1914, that Alan refers to is not a duplicated work, but the very same one that is normally in the Centre George Pompidou. I believe it was destined for Shchukin at the time of Lenin’s confiscation of the collection, having been specially commissioned by Shchukin. Matisse in the end reluctantly sold to someone else. It was eventually donated to the French state by non other than Baroness Gourgaud. Presumably it was lent for this Shchukin exhibition in some kind of belated accordance with Matisse’s intentions.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Good detective work, Robin. I couldn’t believe how similar they were, ( it was!).

LikeLike

However, the first Woman with a Fan that I mention is the African influenced brown one of 1908. The green one illustrated is 1909.

LikeLike

I’ve added that.

LikeLike

Great review. Makes me even more tempted to go into debt to raise the airfare from Australia to see this great show!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Good to see another Melbournian commenting on Abcrit. Hope you were somewhere dry today. Apparently it’s Summer here.

LikeLike

I appreciate Alan’s thoughts on this wonderful show which helps keep it alive. The work by Matisse was fascinating. Alan’s ‘Letter from New York’ ( https://abstractcritical.com/article/letter-from-new-york/index.html ) is worth reading in relation to looking at Matisse and enhanced my pleasure and understanding of looking at this collection.

LikeLike

During the height of the Cold War (1974-1975?) the PIerre Matisse gallery in NYC showed the work of Matisse from the Pushkin museum.I assume it was from the Shchukin collection.I assume also that Pierre being the son of Henri had the international connections that helped make the show happen.It was stunning and taught me things about painting that were not being taught in the art schools here .

LikeLike

Matisse never fails to knock me out. Add me to the list of artists who put him as the greatest painter of the 20th century.

LikeLike

Assuming that Cezanne is to be regarded as a 19th century artist (died 1906), then it is indeed hard to find any painter in the 20th century better than Matisse, though I for one would put him quite a long way down the all-time list; certainly below Cezanne, for starters.

Are too many assumptions made about Matisse? Does he get the benefit of the doubt too often? There is a lot of his work I find compellingly brilliant; but a lot too, that I find now increasingly undercooked… (sorry, Emyr). I’ve been thinking that Matisse needs a greater degree of scrutiny as both a progenitor of abstract painting and as a colourist (whatever that means for painting). I’m still thinking about the Shchukin exhibition, which, like the big Matisse show at the Pompidou in 1993, left me feeling that the big 1910-sh paintings lack focus – perhaps it’s just me, but they leave me perplexed.

I found myself pretty underwhelmed by the big Matisse paintings in the big room (the photo at the top of the post), once I’d gotten over being overwhelmed, if you see what I mean. I include in my general lack of enthusiasm not only the “Pink Studio” and its attendant paintings (the deckchair and the nasturtiums), but also the “holy of holies”, the “Interior Quai St. Michel, with Goldfish Bowl”. I think I’m going to say that, close up and personal, these works are rather dull (though everything is relative and they’d still knock spots off Diebenkorn). All these works look really great when concentrated and disembodied in reproduction, and it’s easy to allow them to become quite compelling in one’s mind’s-eye, without even seeing and examining them; but in the flesh, they dazzle not so much. I’m beginning to realise I like Matisse most when he’s still under the early influence of Cezanne, as in the “Bois de Boulogne”, say up to 1904-ish, or later in the Nice period. The “Cut-Outs” were pretty much written off for me by the Tate’s big show. And now the big 1910-ish paintings that are regarded as significant for abstract colourists, and that I have perhaps taken for granted as being important, are in my mind ready for questioning, big-time.

Is “The Pink Studio” spatial? Does it “extrovertedly open out to meet the space in front of it”, as Alan says. Maybe. What does that mean? Is that enough? Not sure. Is it just a case, as we have already touched upon, of the figurative prompts making the space? I’d say in my experience it lacks any space/depth when you are close up to it. Does that matter? I’m minded to think it does. I bang on about spatiality/three-dimensionality, in sculpture and in painting, to the annoyance of a few who think that I want a return to some kind of figuration. I don’t, and I think there are lots of ways to achieve spatiality in painting other than by depicting volume. In abstract painting, spatiality can be built into the way the painting is made/discovered, right from scratch. There is no sign of anything like that in the bigger Matisses, of them being built in that way, and I miss it. Maybe they are not the good precedent or example for abstract painters they have for so long been considered to be. What they did is open up the possibilities early on of big flat areas of colour. Great colour, maybe. But where did we get with that? I’d say big flat areas of colour are going nowhere at the moment.

I certainly didn’t think much of “The Red Studio” when I saw it in New York years ago, the painting that was so significant for Heron. And what is so good about “The Moroccans”? It’s a weird piece of semi-figuration. I know Alan loves it. Again, in the flesh, I was disappointed. It’s the “in the flesh” thing, ain’t it? It has little of what oozes from the pores of “Bois de Boulogne”. And in the end, Matisse doesn’t get near to the relentless greatness of Cezanne when the latter is on song, does he? (Or Tintoretto.)

And I think, in response to what Richard writes about “immanence” and plasticity, these big Matisses have none of it. To be honest, I don’t really care whether a painting goes back into space or comes out at the viewer, so long as it does a great deal of something – perhaps both things, plus side-to-side and up-and-down. Spatiality and plasticity are both about movement – but possibly more to do with the movement of the viewer through the material rather than any kind of depiction, and such movement may be close to what I mean by “content”, if I may be so bold as to suggest. Colour’s great, but it’s just a tool, isn’t it, for something else?

I think it’s important to have a look at this exchange again. Starting on Feb. 9th, Harry wrote:

To go back to Robin’s earlier comments on the two Matisse paintings, I was reminded of one of Richard’s comments way back on the thread of my Guston/Matisse essay. Richard wrote,

“Maybe this is a bit off topic, but I’m not sure how helpful Matisse can be for abstract painting as it seems to me that the space in his pictures is almost always created or at least structured by a combination of essentially figurative means, namely perspective and the overlapping of recognisable things.

You can see the two clearly working together in “L’Atelier Rouge” 1911.

Without the figurative interpretation of the central area of “La Conversation” 1911 as a window or picture with a man’s arm in front of the lower right hand corner it jumps out way in front of the blue wall. The light blue flowers in “La Fauteuil Rocaille” 1946 are only saved by figuration from sinking below the area of red wall behind. The coussin bleu in “Nu au Coussin Bleu” 1924 becomes a hole without some kind of figurative interpretation.”

It did get me thinking, because one of my criticisms of Guston was that the works are for the most part flat, and rely heavily on the imagery, whether it is figurative or a black blob, in order to set up any kind of distance between things. The space isn’t really built into or wrought out of the light or the handling of the paint. It’s just implied by plonking some ‘things’ in there. Matisse is no plonker, but it got me wondering if any of these criticisms were also applicable to him. If they are, it is in a completely different way.

I watched Alan’s recent talk at the Hampstead School of Art today, and his discussion of Matisse’s Moroccans, Still Life With Aubergines and the Piano Lesson was very much concerned with this issue. Sadly it cuts out during his discussion of The Moroccans and left me wanting more. To what degree do these incredible Matisses require legible figurative things to inform us of the space being presented? Alan talks about the little perspectival diagonals in the Piano Lesson, or the railing on what might be the balcony. Also the association of the colour green with the garden. Does the space remain plastic without these elements and associations, if I take plastic to mean something along the lines of visual and physical cohesion regardless of the subject depicted? None of this could stop me from adoring these paintings, it’s just something to consider if you want to make abstract painting that isn’t like Kenneth Noland’s “Homage to Matisse” 1991. As Richard said, is it ‘helpful’ for abstract painting? Perhaps, if abstract painting could unearth space and content as curious as the mirror in Aubergines, or as visually astute and humorous as the melons posing as Muslims at prayer or vice-versa in the Moroccans, though this seems quite impossible. Or has abstract painting achieved such a feat already but in a different currency, and we articulate this value in different ways, because these things don’t have such clear and intended figurative associations.

I don’t think that Diebenkorn can provoke the same level of curiosity about the role of imagery, spatially or otherwise, because for some reason his paintings often look more flat when he puts a figure in it, and so you wonder why it is there at all. It seems rather meaningless.

Richard replied:

“Or has abstract painting achieved such a feat already but in a different currency, and we articulate this value in different ways, because these things don’t have such clear and intended figurative associations.”

I think this is a very interesting question to which I have no answer, just the following thoughts…

Deep space in abstract painting always seems to have (and possibly arise from) figurative associations unless it crudely destroys the surface (Howard Hodgkins’ “framed” paintings), or is uncommunicatively atmospheric (and therefore possibly also figurative – sky, deep water, fog).

Maybe our spatial perception acts on a principle of maximum economy – deep space is only seen where it is absolutely necessary in order to make sense of the optical phenomena in conjunction with what we already know about the world (the physical size of things etc.) In an abstract painting it is hard to see where this absolute necessity might come from. The spatial effect of two adjoining colours both present on an intact surface would then be limited by this principle of economy to a shallow push and pull.

Can a meaningful wedge be driven between the ideas of plasticity and spatiality and could one “different currency” (see above) be plasticity? More plasticity wouldn’t necessarily imply deeper spatiality. A pronounced plasticity would be happy in shallow space. To me “plasticity” also has overtones of immanence that “spatiality” doesn’t have. The colours in a highly plastic painting could come back (optically) to the surface just as strongly as they recede, so the painting can seem to be advancing into the viewer’s space rather than just opening up a box of space in the wall. Abstract painting would have a huge advantage over figurative painting in this respect, since it has fewer problems with ingrained habits of figurative interpretation stopping the eye from bringing colour up to the surface.

Harry:

I think the potential for abstract painting to return serve with the colour could be an advantage over figurative art, if it wasn’t so comparatively limited in regard to how it travels back into the picture. It’s apparent that we get very strong sensations from this phenomenon in painting, and that these sensations are not equal either, meaning that there is huge sophistication involved in arranging colour to elicit such a response, and that it takes a good eye, depth of feeling and hard work to pull it off. In the wrong hands, it will just sag. And to be honest, I don’t think I’ve really seen (in the flesh) enough painting of serious ambition that attempts this, so my views have some limitations, based on experience.

So does the sensation of strong optical pressure from the colour match the intensity of sensation experienced when perceiving deep and coherent space? Is it possible to make the kind of painting you might be imagining, Richard, one that comes forward as strong as figurative painting can recede? This would be a kind of illusionistic “push”, and not a literal one, as in Stella. It’s intriguing, but I’m trying to imagine such a thing, and keep seeing myself looking at a painting while wearing 3D glasses.

On what might be a related note, John Pollard posted a short youtube video about Tintoretto on twitter the other day. It was about “The Miracle of St Mark Freeing the Slave” http://www.wga.hu/html_m/t/tintoret/3a/1mark.html , a painting that I’ve been fascinated by in reproduction for the last few years. Towards the end of the video, the speakers make a point of demonstrating how the structure is underpinned by strong recurring colours, namely these deep reds and orangey golds that burst forth yet also hold and ensconce the procession of characters, and by the looks of it, are somewhat undermining the insistence of the recessional perspective that the group of figures construct. The strong colours are part of this receding form, but they also break free from it (and I know this is different to what you alluded to, Richard, which would be a kind of painting where the colour re-asserts itself across the whole surface).

I’m not saying we should try using strong colour to hide spatial figurative devices in abstract painting. Also it would be a disservice to refer to anything in the Tintoretto as a ‘device’. Devices are for cheap semi-abstract paintings like Howard Hodgkins’. I’ll just say that the Tintoretto is both highly considered in it’s structure and design, yet tremendously free in paint application and spatial possibility via the inventiveness of forms like those terrific foreshortened bodies, one at the bottom facing up, the other at the top and upside down (remarkable). There’s so much going on in there, too much for him to have predetermined despite the strength of his design.

I might have gone off track a bit, but the problem I sometimes have with discussion about colour in abstract painting and what it can do spatially, is that the word ‘theory’ is always lurking, no matter how many times we acknowledge the fact that no-one knows what two colours will do when placed side by side. There seems to be an implication that if the colours are wrong, just change them until they ‘work’ (I’m aware that the reality is more complex than this). The fixedness of the format (in some cases) will support this solution by not diverting our attention from the colour relationship. The spirit of the Tintoretto bespeaks a freedom of activity, using a whole range of means to alter, invent, change course and uncover things that could not have been found if one had to strictly adhere to a figurative design or an ‘abstract’ format (contradiction in terms?). Maybe this freedom is the unrealised advantage of abstract art, but in all likelihood we were probably more free when to be figurative was not a sin, because space itself was not compromised. Tintoretto could move wherever he wanted to go.

Richard:

I see what you mean about the 3D glasses!

But I can imagine perceiving the reassertion of the surface not as a kind of mirage hovering in front of the canvas (some op-art does this and it is only annoying), but as a reinforced presence. Joan Mitchell springs to mind. I don’t suppose you got to see the RA exhibition, but I thought that “Mandres”, the smaller of her two works exhibited there (in spite of its characteristic lack of resolution) had a presence that was hardly equalled in the rest of the show. I think this had a lot to do with the fact that, when focussed upon, every patch of colour was totally there at the surface and even the “background” white came forward in a lot of places, where it overlapped the “figure”.

But there we are by figuration again…

Some of Hofmann’s (“In the Wake of the Hurricane “) and de Kooning’s (all I’ve ever seen from 1977) paintings have this quality in spades too.

Harry:

Didn’t see the RA show, Richard. The closest I got was a catalogue kindly lent to me. I did find “Mandres” very striking in the book’s reproduction, despite my finding Mitchell’s work quite unresolved and repetitive. But where there was activity in Mandres, I liked the look of it. Like you say, present and direct, not veiled and submerged.

But maybe submerged could be ok at times too, if it’s not being reverted to as a format or a device for making the painting seem to exist on a plane back a length from the surface.

Sorry about the 3D glasses remark by the way. Couldn’t resist.

John P:

For me an abstract painting can make use of its non figurative, i.e. recognizable pespectival, depth and space. I verge on calling this ambiguous space (I know Robin doesn’t like that word) as it is not straightforwardly recognizable. You can do this more or less simply, push and pulling with clearly defined simple colour areas, perhaps in repetition and pattern, or you can break it up.

As my bias is towards work that you can enter into an ongoing rich relationship (I hesitate to make an analogy with good human relationships, but I just have). This being the case work where explicit areas in a painting belong to more than one larger area fascinate me, where they play multiple roles. Of course complex diversity can become chaotic unstructured clutter when it doesn’t work (that should go without saying but I end up repeating this!).

And clearly although Tintoretto is a figurative painter he breaks up ‘normal’ perspectival space (through structure, through colour, both?) which seems to serve the painting’s value (I hesitate to call this its ‘abstract qualities’ but the term helps me).

Perhaps many great painters do this (breaking rules of recognizable space – Matisse comes to mind).

Harry again:

A while ago I had a conversation with a friend who had just visited the Prado, and so El Greco came up. Before too long, my mind drifted off towards Tintoretto, and I started to think about why El Greco didn’t do as much for me as he used to. I think it’s because El Greco, wonderful as he may be, obsesses over the unique forms he creates, running them into each other across the surface of the painting. Tintoretto on the other hand obsesses over space, and in some ways, despite his own uniqueness of form, seems to succeed in making the forms disappear, giving themselves up to the “air” of the world he was creating. Greco’s world is a flatter, more stylised one (obviously). He is Picasso to Tintoretto’s Matisse perhaps.

John P:

Picasso had different interests to Matisse which partly explains the overall structure of his paintings but I do like some of his work where there is less of a simple figure ground separation and his colour/shapes vibrate and weave throughout the work in a more interesting fashion.

Robin:

With regards to Tintoretto, who keeps cropping up in the conversation at the moment, he is without a Renaissance equal in his unique uses of spatiality, and hardly ever does he let compositional devices and mannerisms get in the way of imaginatively opening out the picture-space three-dimensionally, whenever and however he sees his chance to do so. It is for this reason that I personally value his work as a peerless example of relentless spatial ambition. A greater part of the real content of Tintoretto’s best painting involves exercising the most imaginative and spatially-projected interpretation of each theme or subject matter that he can possibly invent, often returning to the same space-theme again to crank it up another notch. Such focus acts to the exclusion of more conventional and two-dimensional Renaissance notions of compositional completeness (and also, I have to admit, acts sometimes to the detriment of surface, and all that is sensuous about paint and painting. That’s also the case, I noted today at the Dulwich Picture Gallery, with much of Poussin’s output). A study-in-depth of Tintoretto’s art will reinforce the idea that great art must be driven by content rather than superficial form. As Harry puts it: “The spirit of the Tintoretto bespeaks a freedom of activity, using a whole range of means to alter, invent, change course and uncover things that could not have been found if one had to strictly adhere to a figurative design or an ‘abstract’ format”…

LikeLiked by 2 people

I take your point, though no apologies necessary. I think you might be somewhat surprised to know how narrow my specific admiration is for Matisse. I take different things from each ‘epoch’. I would say the Vence interiors ( in the flesh ) are like nothing else on canvas – (for me), the early fauve ones important and at various times in between lots of envy inducing moments – this last point is shared by similar feelings to a lot of Picasso things. I feel slightly avaricious towards their work but that’s not enough in itself. I do not go overboard for the pink or red studio actually, the cubist riposte stuff either. (and was always surprised how revered they are) I find myself still in complete agreement with myself as a student. That was how I felt then and these feelings are still unchanged now. Having said that I don’t think that connecting with Art creates such static unflinching certainties; I may well change my mind at some point – I have not seen this show anyway in the flesh – though know a lot of the work from numerous other encounters – so couldn’t comment with an up to date take. Although I think Tintoretto is fantastic, I am not convinced (sorry) he is the way to go. He constructs – as you said – cranked up spatial offerings taking contraposto and spiralling to dizzying heights but … then (!) seems to “colourise” things – like a dyer. In his work: form leads, colour follows. Whereas Titian seems to drag his colours out of the forms as they are being made – they do not feel set up but discovered. Oh I know this was not the case – strategy was their watchword but Titian doesn’t let the air in, in the same way. I can envisage moving in to a Tintoretto painting and looking sideways at the bodies – it feels very “sculpture-fied”. Titian’s paintings exist completely synthetically for me as paintings and nothing else. Matisse spent a long time in the thirties drawing; the lines are so relevant – I do not see them as drawings per se but akin to his colours – “forces” . Those lines hit me with a different significance but still a cherished one none the less. I believe it is all colour anyway – you can call it other things but it comes back to how the colour is organised. Colour is as difficult and demanding as one wants it to be (or as unimportant too). Any artist I admire does not have all the answers ; its more about the existence and strength of their ‘echo’ as much as a specific example; and although I think it’s fine to listen to these echoes – it is more important to make our own noise….pardon me!

LikeLiked by 2 people

I’d like to get back to John Pettenuzzo’s comment in the same thread, the relevance of which to several of the themes being discussed on ab-crit I have only just appreciated.

Symbols are a key element in the writings of Susanne Langer. I have just discovered her “Feeling and Form” and find myself applauding nearly every page.

Some of this might be “old hat”, but I never see Langer mentioned anywhere (her books appear to be out of print) and she seems to me to be just as instructive as Fry, Greenberg, Fried and Co.

She starts with something like Clive Bell’s significant form, but rubbishes his “aesthetic emotion”.

Instead she proposes that successful artworks share their structure with “patterns of sentience” and can therefore symbolise our subjective experience in the sense that John Pettenuzzo has brought up: Symbols have an equivalence of structure that allows for a completely symmetrical relationship – each side can symbolise the other, though we generally take the more readily manageable of the two as the “symbol”. Signs by contrast are merely conventional stand-ins without any intrinsic similarity to their reference.

In Langer’s account the content of an artwork is not a meaning but an import (or significance), this being its potential as a symbol for some part of our subjective experience.

For Langer, symbols are an essential ingredient for the ordering of experience. The artist learns as much from making an artwork as its recipient can learn from seeing or hearing it. And the symbols of an artwork are non-specific – they can be used by different people at different times for completely different areas of experience. This is why it is misleading to speak of the language of an artwork; language being in its nature more specific.

Seen like this, a simply structured artwork can only serve as a symbol for simply structured feelings/patterns of sentience. A complex artwork is both richer and more versatile because it contains many overlapping patterns, each of which can in turn be used to symbolise (and therefore to help grasp/understand/share/come to terms with) a wider range of subjective experience.

For me, Langer’s ideas go some way to explaining that feeling of “rightness” that good art conveys and the sense of delight and discovery that it can give us.

They would also seem to provide a plausible account of at least one kind of artistic content and a convincing argument for more rather than less complexity.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think I see what you mean. Not read Langer.

It would be good to hear more from John Pettenuzzo on the “atonement of form and content”.

LikeLike

Complexity does not equate to form. More complexity does not equate to more content. To explain why one artist is richer in expression and formal strength than another, you have to bring in other factors — breadth of vision, expansive form, subtlety, emotional depth and probity, grasp of the essential disciplines of the art-form, relevance to the central concerns of the era in which they find themselves, a sense of history, relevance again.

JS Bach synthesised and built upon the most “progressive” elements in Italian, French, Flemish and German music of his predecessors, to such an extent that he appeared a giant anachronism to his immediate successors. Today’s anachronism is tomorrow’s vanguard (if we lived in an honest world).

“I love all images and hate all symbols” — P. Heron.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes Alan, all those things, but none of them rule out complexity. Complexity may make some things more difficult – clarity and resolution spring to mind – but I see no extra problem combining it with breadth of vision, expansive form, subtlety, emotional depth, probity etc.

Langer doesn’t equate complexity with content. For her the content is the artwork’s potential as a symbol, and this in turn depends on all those factors that you mention.

I don’t think there’s so much difference between an artwork functioning as a potential symbol (in Langer’s sense) for subjective feeling and an artwork communicating directly from subconscious to subconscious, which I think was your way of putting it.

Maybe Langer’s account puts a special emphasis on the equivalence of structure (in its broadest sense) between artwork and subjective experience; hence the equation of complexity (but also of clarity, subtlety etc.) between artwork and experience.

At the end of the day, I don’t think any theory of art can ever be “correct”, but I do think that they can embody intuitions and perspectives which, set against one’s methods and results in the studio, can prompt a useful questioning (which might then be a route to more depth and probity).

Patrick Heron is surely using “symbol” in the sense of “sign”.

LikeLike

And I’d add — clarity of thought. The knowledge of “what to eliminate, what to magnify”. It seems the world is full of people who know far, far more than they need to know, and it stands in the way of their making successful paintings. ” These terribly conscious birds want to turn it all into talk, into knowing, and so life, which will not be known, leaves them” (D H Lawrence).

LikeLiked by 1 person

Of course, clarity is all, but you are stating the obvious, What is less obvious is the consideration that a complete lack of complexity in the input of “content”, or whatever you want to call it, will give you too little to work on, too little to clarify, too little to “synthesise” etc. I’m sure you don’t want the fake clarity of Minimalism any more than I do, Alan, but that’s what you get in 90% of abstract art – minimalism with a small “m”, and it’s because a lot of abstract artists get it into their heads they can start with next to nothing in the pot. Minimalism is NOT clarity of form.

The more complex the content that gets sythesised, the greater the art, in my opinion. So I would say that – all else being equal – more complexity DOES equate to more content, and more content DOES in the end equate to more purposeful and clear form.

Yes, we want the clarity of this:

where the very first glance (even in black and white and low res!) tells you that you are in the presence of greatness, of visual form of the utmost clarity; but you also know Cezanne backs that up with a sophistication and complexity of content that will keep you sustained well beyond that initial hit, and the paintings will withstand continued and close scrutiny and keep on giving – more, more, more! You just cannot get that if you start from a simplistic position regarding the content of the work.

LikeLiked by 2 people

And P.S. it cannot be all subconscious spontaneity!

LikeLike

P.P.S. for clarity without any content, and format without any form, see McKeever…

LikeLike

“And I’d add — clarity of thought. The knowledge of “what to eliminate, what to magnify”. It seems the world is full of people who know far, far more than they need to know, and it stands in the way of their making successful paintings. ” These terribly conscious birds want to turn it all into talk, into knowing, and so life, which will not be known, leaves them” (D H Lawrence).”

Good quote. If our fundamental, most basic relationship to the world were a relationship of knowing, making and experiencing art would not hold the interest (and therefore the value) that it does and always has. Modernity (AKA the “age of science” and skepticism) can be characterized as (among other things) an over-valuing of knowledge, an over-intellectualizing of the world and of ourselves. Hence the pressure on modernist artists to find ways to assert the autonomy of their particular kind of activity in a world that is in effect reduced to a vast collection of objects. I think this pressure has never been greater than it is now.

LikeLike

I also think that words like “complexity” and “content” are so general and therefore vague that relying on them to sustain a debate is not likely to lead to resolution. If a work of art strikes me as effective and convincing, it is unlikely that its complexity or its content are going to illuminate why and how. (For example, the phrases “more content” or “less content” don’t mean anything to me.)

LikeLike

Maybe that’s because you are an end-user rather than a producer of art. It’s obvious to me that those phrases do mean something to some artists. But this is where we disagree, I suppose. Your experience of art may bear no relation at all to the experience of the artists who made it. Artists have to think about what they are doing, even if what they are doing is/looks spontaneous. To suggest anything else is irresponsible. But all you may see is the spontaneity.

I think there is an open-ended discussion to be had about whether the conditions of clarity and “wholeness” are essentially changed in some way in abstract art, from those seen in successful figurative art such as the Cezanne. Will those end conditions be achieved in a different way from figurative art?

In conditions of more complexity than has been normally the case in abstract art to date, it seems to me (from experience, not theory) that the notion of “wholeness” is stretched in some way, or extended, or redefined slightly. The nature of clarity might change too… and I think this is linked to what I have said about the nature of how those large Matisses are made, how they have a certain clarity from a distance or in reproduction, and how they feel to me far less defined or specific when close-up and personal, and you take on board how they are made as a part of one’s perception of them.

In abstract sculpture, such issues seem yet more compounded, having the potential for greater complexity in the infinite possible viewpoints of something really three-dimensional; plus what is perhaps a greater involvement with exactly how the work is built. All very exciting and not to be gone back on.

And by the way, it’s worth noting that even clarity of thought doesn’t guarantee anything.

Too many words? Too much intellectualising? I don’t think so. Not enough, and not of a high enough calibre. We are in strage times in art, everything is broken, and we have a lot to sort out. We do make a little progress, it seems to me. Going back to the high modernism of Carl (and Alan?) is not an option. We are into something else, perhaps.

LikeLike

If I am stating the obvious, why the difficulty of taking it on board. You are still tub thumping away at the same old mistakes that were debated at length in the dialogue between Tim Scott and Robin Greenwood. Still talking about content being “put in” to a work, as if the more you put in the more “content” there will be. If I knew how to put up an image on abcrit I could show you a thousand examples of paintings where this is obviously not the case, but one example I have offered you before is Kandinsky’s 1917 abstract pictures. Just to say that they are bad paintings says nothing at all about why. I’d say that what they lack is any sense of the sorts of broad architectural conception that registers spatially in the context of pictorial and abstract art.

And I repeat again –” The content of painting is our response to the painting’s qualitative character, as made apprehendable by its form. This content is the feeling ‘body and mind’. (Robert Motherwell). For there’s the rub. That great imponderable “quality” is never answered by “putting in” more and more stuff and heaving it around. Cezanne, for instance, is the most subtle and nuanced, astringent and ascetic of sensualists.

LikeLike

Or Kandinsky Composition VII 1913 .

LikeLike

LikeLike

With regard to Composition VII I think that if it is failing, for the reasons that Alan mentions, in the context of pictorial and abstract art then it could well be worth taking a good look at. Could it be that that perceived failure (I am presuming bad equates to failure) is because it doesn’t conform to the viewer’s pre-conceptions and expectations. I accept that the ascribed difficulties of this work could in fact be greatly increased when standing in front of it as it is approx. 200 X 300cms but is that really a criticism of the painting or is it just that it takes the viewer out of a comfort zone that is perhaps strongly related to taste and an expectation embedded in established criteria. Whatever we choose to call it, content or whatever, there is plenty of visual stuff in there to try and take in and one would hope that the intensely graphic nature of the small image would be highly mitigated if standing in front of the real thing. It seems to me that this is a challenging work that is grappling with a great number of elements that can be used to make a painting, shape, colour, line mark etc. without a recognizable ‘architectural’ plan or use of graphic devices to pull it harmoniously together. I rather like that.

LikeLike

Here’s a nice example of the work of another of “the most subtle and nuanced, astringent and ascetic of sensualists”… the expert on abstract painting you so love to quote:

LikeLike

I’m not sure what I meant by the phrase ” the atonement of form and content. ” It came into my head as I was writing my short comment, musing on abstraction,the symbol and faith. On second reading, it sounds to me for all the world like a classic piece of pretentiousness. But it was an aspiration too, I think. The desire for an alliance with the symbol. Maybe a bit like the way the deeper physicists delve into matter, the more metaphysical their researches become; persuading them into the arms poetry and its metaphors or even back to God.

I’m not an abstract artist,but what happens to abstraction concerns me too, somehow. Without some kind of alliance ( ?? ), I fear it becoming a niche genre.

LikeLike

I mentioned the symbol when discussing Rothko’s paintings. What I had in mind was C.S. Peirce’s description of types of sign, his triad of ‘index-icon-symbol’. Abstract Expressionism employs these three types; gestures are ‘indexical’, some images are ‘iconic’, in that they resemble their referent, and some are ‘symbols’, related to their referent by cultural convention. To function, signs have to be legible. They require a space and order. This is a non-figurative space, not subject to the laws of gravity, acting more like a grid that separates each sign to avoid confusion. It’s also a space that most people, anyone who has read a newspaper for example, can understand and navigate.

Rothko makes deliberate use of this space to make his paintings legible. The elements are separated so each part can occupy an allocated domain, without competing with other elements. As the structure takes on the characteristics of a symbolic order the planes are credited with the cultural value symbols have. They don’t have to mean anything. It’s their inclusion in a symbolic system that makes them seem to be bearers of significance.

What matters as much is that Rothko figured this out from looking at European painting, combining the symbol and the plane to increase the level of abstraction. For good measure the planes are constructed from gesturally applied paint, adding another level of potential significance to the work. Again, the indexical gesture doesn’t have to ‘mean’ anything.

Rothko’s work varies in quality but his ambitious abstraction deserves recognition. His painting is often misunderstood, and praised for what maybe the wrong reasons. To be fully appreciated he is an artist who needs to be rescued from his admirers.

LikeLike

I see what Robin has done there — take the worst example you can find of an artist’s work and use it against them, thereby sidetracking the import of what they have said. You know what they say about sarcasm, don’t you.

LikeLike

Not sarcasm, mate. I can do sarcasm better than that. No, just tit for tat. You put up a crap Kandinsky to rubbish my argument, I put up a crap Motherwell to rubbish yours. But my example is the more telling because it’s closer to home, to what people do now. Its abstract painting at the apotheosis of boringness. It’s within a gnat’s chuff of conceptual art. Talk about over-intellectualising…

I’m not sure if I’ve seen either of these paintings, but going on other examples I have seen, I’d say they both suffer from being almost totally concerned with banal compositional decisions. Kandinsky is a great painter up until 1910 when he becomes abstract, then he starts designing his paintings AND over-intellectualising them.

Not sure Motherwell could be called great at any time in his career. Maybe he is quite a good writer and collager, but as a painter, no. He even repeats his really boring paintings again and again. I’ve yet to see a really good painting from him. No doubt you can put me right.

LikeLike

Two Motherwells I have seen in recent years that I liked were Western Air 1946-47 MOMA.NY. Personage with Yellow ochre and White 1948 MOMA.NY. Black and White 1961 Houston Museum of Fine Art (not the print) is a brave impulsive statement which few would dare for, or dare to leave unadorned, and Chi Ama, Crede 1962 Phillips Coll. Washington has “the gift to be simple.” It originally had dark borders at either end, rightly removed.

LikeLike

Heres some of your pics:

https://www.moma.org/collection/works/78691?locale=en

https://www.moma.org/collection/works/78450?locale=en

https://www.1000museums.com/art_works/robert-motherwell-black-on-white

No future in that lot, is there?

Here’s an example of a work that proves my argument:

Mark Skilton, 2016. Had Mark not gone out of his way to invent lots and lots of varied and exciting “content” at an early stage in this work, he could never have then gone on to synthesise it all into something as plasticaly and spatially and three-dimensionally coherent as this. That takes conscious effort as well as intuitive spontaneity. This work is stuffed with content, stuff doing stuff, most of which was made early doors, after which the sculpture made itself without the necessity for an overarching architecture or idea. In my opinion.

I could have picked quite a few works by quite a few people out of Brancaster… particularly from last year.

LikeLiked by 1 person

These latter two are not “worked up”, laboured, the worst of sins in painting. There should be a continuous libidinous flow of feeling from first to last, whether the work is complex or not. Even such sustained effort as obviously went into Moroccans or Bathers by a River can’t be described as laboured or worked up. Or that Cezanne Mont St.Victoire reproduced above either. And you still haven’t really said why that Kandinsky is bad. I see little evidence of either design or intellectualising. But I do see muddle instead of music.

LikeLike

Yes well we agree about the Kandinsky! I hate it! It’s muddled! OK! It’s a muddled, over-thought, over-designed, graphic mess of a thing. I have disowned it from the start. That proves nothing other than a mess is a mess.

And I still think Motherwell is real boring.

LikeLike

And, unless you are Geoff Rigden, God rest his soul, you can’t paint like Motherwell now, it’s pointless. It was rather vintage retro even when Geoff did it.

LikeLike

One more thing about the Motherwells – they are all three as near as damn it figurative. (All the “Open” series are, are they not?) Does it matter? Yep.

LikeLike

Look, here’s Motherwell:

Karl Bielik, “Swerve” 2014

It’s ‘not “worked up”, laboured, the worst of sins in painting’.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Robin, please elaborate this statement: “This work is stuffed with content, stuff doing stuff, most of which was made early doors, after which the sculpture made itself without the necessity for an overarching architecture or idea.”

LikeLike

(jumping in sorry) The crux of making art lies in the attitude to spontaneity and having a skill set to tackle problems as they arise. Problems that arise when things are being made – the friction of creativity. When you see strategies which are opaque the ‘content’ is stifled. Mark puts bit of steel together. When he is doing so he is clearly not looking for a predetermined outcome which these pieces are going to fit into. He seems to be looking at the pressure points of how one piece of steel (which in itself offers up a momentum to work with) meets another – and how these points accumulate in complexity as more is made. The work starts and each new piece of steel has a consequence. After a time I would bet that certain ‘phrases’ exist and when new ones are created, adjustments could be made to earlier ones. He keeps on moving the stuff, checking, offering, finding specific ways to connect everything – perhaps adding a forged piece which adds a different ‘note’ to the work as opposed to plate pieces. It’s all about handling the steel to generate energy in the work. All the time working the air with the steel. Moving things, moving yourself. Bringing it back into painting – sight is fluid, we move, scan, scrutinise. This why Cézanne is so relevant. He is looking really hard, moving his eyes, checking, synthesising. This is the antithesis of plonk and display work in which the air is inert. You have to get the electricity into the work somehow. It can end up simple , but not simplistic, or it can be complex but not complicated. Ultimately this all takes an “humility” (there is no other way to explain it for me) Either you serve the work or it serves you – hence careerists will have less of a regard for the inquiry and more for the enquiries. Alan’s quote from Lawrence is excellent too.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Carl, Emyr has answered your question and I 100% agree.

LikeLike

This all sounds really helpful Emyr.

However, I do think a succesful complex work will always give me much more of a rewarding experience and relationship than a successful simple work. Note a succesful work. Is that just a matter of taste?

And I would also emphasise the artist’s critical judgement and ambition as being of paramount importance. You can have all the skill in the world but if your judgement and ambition is off it will lead to very uneven work, at best.

LikeLike

… But what is interesting to me is that you could argue that the Karl Bielik is spontaneously arrived at too. So what makes the difference – the gulf – between Mark’s and Karl’s work? It’s lots of things, but for me, most fundamental of all, is that Mark’s instincts are to keep loading the thing with content because he trusts himself to sort it out, and he knows in the end if he can do that (no guarantees) he’ll have a richer, more profound piece of work that will stand a great deal of looking at.

LikeLike

…and why would you NOT want to make things that stand a great deal of looking at? Well, only if you have some cockamamie idea about abstract=simplistic.

LikeLike

The other thing to say here, Carl, is that Mark’s way of making a sculpture (along with probably all the other Brancaster artists) consigns your ideas about “intentions of the artist” to the bin. Yet it by no means precludes “intentionality” in the work itself, in how it works and looks.

LikeLike

Nothing “consigns my ideas to the bin” automatically, as it were; consigning my (or anyone else’s) ideas to the bin requires a lot more than the making of objects that are not consistent with these ideas.

LikeLike

“The work starts and each new piece of steel has a consequence.” What kind of consequence? There are physical consequences in the sense that another piece can be attached to it due to its position, and the size and shape and angle of the attached piece is limited and constrained by the physical qualities of the first piece. This is what I think of as an additive mode of composition, and its risk (artistically) is that of arbitrariness, one piece being attached to another in ways that don’t really represent decisions as much as physical options opened up by the literal characteristics of the pieces. Then there are consequences that may be thought of as implications. The following-through of implications requires decision-making and is motivated and governed by intentionality, the desire to create significance. Consequences are like conclusions to be drawn in a sentence or a sequence of sentences; one thing follows from another according to the logic of revelation, illumination, enlightenment, subject of course to the rules of grammar. This kind of consequentiality is to be distinguished from that of cause and effect, which governs events in the world of objects.

LikeLike

‘Composition’ is for amateurs. Simple works can be complex.

LikeLike

The first sentence is not true. As for the second sentence, simplicity per se is no more indicative of artistic value that is complexity. You’re putting too much stock in my use of the word “composition”. My reference to an “additive mode of composition” is a mere observation concerning the way in which way it appears to have been made. My point has to do with the way in which, at least to my eye based solely on a photograph, “consequences” (your word) are generated in the sculpture. It’s the difference between a collection of words and a sentence with discernible syntax.

LikeLike

I’m an amateur, so that’s fine: I’m happy to question what composition means but I wouldn’t throw out the idea entirely.

Does a simple work that is complex rely on the complexity of the viewer and their interprtations though? Does the complexity reside at all in the actual simple work?

LikeLike

Emyr – I know it was just an offhand remark, but I am an amateur too, and I wonder at your apparently derogatory use of the word. Do you really think that amateurism is an obstacle to ambitious art? I´d have thought that in today´s art market, it might even be an advantage. There seem to be enough professional artists who are cynically producing whatever sells.

I´m also not sure what you mean by “composition”. If it´s the same as “resolution” then I´d say it was very important and belongs to the artistic integrity and humility that you so well describe in your previous comment.

LikeLike

No it’s not meant in any way derogatory. I’m not that bothered how one classifies oneself either. You are right to point this out. Composition tends to concern itself with ‘procedures’, established values, rule of thirds, golden section, all the usual checks and balances of easel painting, etc etc – things that arrive where you think they will. Too many people work with this in mind and it inhibits them. Resolution is something different. Composition can be covert too – you need to guard against it. Velasquez paints a Pope – a guy on a chair, pretty simple, but it’s very complex. Bacon does it and its complicated not complex, doesn’t really do much and ends up looking like a bit of a skidmark of a painting – literally – though possibly intentional – maybe it’s too composed? (not being derogatory again)

LikeLike

OK, Thanks.

I see what you mean.

LikeLike

“The following-through of implications requires decision-making and is motivated and governed by intentionality, the desire to create significance.”

Barring the odd Provisional Painter, there are no artists who don’t in some vague sense want to create significance. But vague it is, and I’m going to repeat your own mantra, and say that is meaningless. And useless as well, to the artist trying to make something new. And it’s going to at the very least get in the way, and at worst lead to a downright disaster, if it’s anywhere near to being their conscious intention whilst making work.

As for “the difference between a collection of words and a sentence with discernible syntax.”, I’d say the Skilton is well on its way to being at least a good short story, if not a full blown novel. That in itself might be something new – abstract sculpture that is a lot more than just a one-sided image.

LikeLike

Kandinsky’s ‘Composition VII’ is pretty good; it’s OK to like it. If you value complexity -lots of stuff happening – you should think it a remarkable painting. It consists of an overload of signs, (symbols) without a symbolic order. It’s illegible, like a palimpsest, which makes it interesting. But it is also devoid of that frozen, illusionistic space that dominates Kandinsky’s later works.

It does have an internal organising structure. The diagonal ‘fold’ that bisects the rectangle creates two fields that play off against each other, influencing the polarity of the elements that they respectively accommodate. The colour is refreshingly unnatural and advanced.

If Pollock’s ‘Blue Poles’ is ok, which it is, then so is ‘Composition VII’.

LikeLike

You can no more ” put in ” content than you can put in profundity. Content is character, an aspect of your character. It is an expression of who and what you are, like it or not. As the bible says — what man by taking thought can add one cubit to his stature. Try to find out who you are, which means more of an unveiling or revealing than an exertion of will or a pitting yourself against other’s complexities. Complexity will grow organically if it must but not all the time in every work. I think Mark was lucky in that one, as he readily admits if you revisit the video.

LikeLike

Seems to me we are using the same word to mean entirely different things. I’m sticking with “abstract content” as something you can put in at the beginning of a work, because to do so is useful. Whereas, as you admit, there is nothing you can do about your “content” as an aspect of your character. Pointless to talk it up, I agree. So that particular argument about content is over (though I happen to think ones character is more mutable than you suggest).

But its really annoying for you to say Mark is just lucky. Every artists needs a bit of luck, but that sculpture was also the product of a whole lot of other things, including the conscious input of not only Mark himself, but the whole of the debate on Brancaster from Mark and other people, and traceable in the debate about sculpture (and painting) going back for 4 or 5 years previously. I would be so bold as to say that that particular sculpture would not have happened as it did without Brancaster – and there is absolutely no luck in that. But of course you couldn’t possibly acknowledge such a notion.

And, I repeat, as an example to back up my argument I could have picked quite a few works by quite a few people out of Brancaster. You can stick with unveiling yourself if you want, and I’ll stick with the unveiling of something much more interesting, happening year on year in the Chronicles – the opening out of our knowledge about the advancement of abstract painting and sculpture.

LikeLike

Bruce Gagnier often talked about changing your work and changing your life in his classes at the Studio School. I exerpted this exchange between Alan and Robin, and sent it to Bruce. Got this nice elaboration back:

“I think Greenwood’ s point about character as mutable is to the point. Gouk should pay attention. The direction of the mutability of character is determined by content…, the desire for meaning. It mutates according to the strength of that desire and that is the source of content fir a life in work. That is why Dekooning and Mondriann could in the end distill the content of their desire the formation of their inner lives to a given content. It takes effort and is not as Gouk suggests …. already there. Change your work to change your life and vice versa.”

LikeLike

Ah, that Bruce! He’ll not be unveiling himself any time soon then.

By the way, Alan, (pay attention there, Gouk!) I’m not sure about Montrose, but down here in London you can get arrested for it.

LikeLike

Actually, I think Brucie might have yet another very different definition of content from me, by the sound of it.

LikeLike

Questioning and reflection and awareness of uncertainty in one’s work helps keep one on one’s toes, not get complacent, and be open to discoveries. While agreeing that character and both personal and art heritage is really important it can’t ‘determine’ what you do.

While overwhelming anxiety and over thinking will be destructive a certain amount of worry and anxiety is fine, even necessary, and I would say can add to one’s ‘stature’.

LikeLike

Why only going back four or five years? Oh, I see, it’s because art starts from scratch with Brancaster, as we all know by now so often have we been told. What about the debate about sculpture and painting that has been going on all during the 1970s, 1980,s and 1990,s where you and your colleagues were formed and on which you rely for most of your values. No one said character is immutable. Of course character grows in tandem with engagement with a discipline. That is too obvious to need stating, is it not?. But only Brancaster makes that possible? All I can say is you better be right, or you’re in for a hell of a roasting. Here we are again — we begin by talking about Matisse’s greatest paintings and end with the claim that Brancastrians have surpassed all of that, and are doing something radically new. And in comes Tintoretto’s Grand old Oprey again. For gawd’s sake — get with the “advancement of abstract painting and sculpture” that has been going on since 1900 and have the humility to recognise that you are a small cog in a much bigger wheel.

LikeLike

I’m definitely right.

LikeLike

Chances are, you’re wrong.

LikeLike

I’ll take my chances, thanks, and not play safe.

LikeLike

Robin, without wishing to sound preachy ‘I’ll take my chances’ strikes a better, more confident yet at the same time more humble note than ‘I’m definitely right’

This thought from Sister Julienne of ‘Call The Midwife’ ( A British TV fictional series ) ‘Certainty is fleeting, that is why we must have faith’

LikeLike

And when my article The Key Paintings of the 20th Century is finally published, you may systematically try to contradict it line by line, but you won’t contradict it in paint on canvas, nor will any of your Brancaster cohorts. They will just be adding a few footnotes to an ongoing development that began before them and will continue after them. Geoff Rigden for instance merits much more than a sidelong glance and a dismissive quip. He represents the opposite pole to the one being pushed at Brancaster, and his work has an authority and a conviction that demands respect and will endure. If it relates to Motherwell in any way, it is to the best of Motherwell.

LikeLike

How are you getting on with your own personal Key Paintings of the Twenty-First Century?

LikeLike

What happened to that Robin Greenwood, the one that promoted Geoff Rigden at the Poussin Gallery and commissioned a sprightly and intelligent essay from Cuillin Bantock. Before the messianic phase. Or perhaps you are saying that John Bunker has superseded Geoff. Why did John not take up the opportunity to review Geoff’s retrospective at APT last year. Collage is right up his street isn’t it. And why were none of the other Brancastrians there? Why were they not at the opening of the Stockwell Show at Greenwich either. Presumably it’s because they think they have superseded all that old stuff. I’ve news for them. They haven’t.

LikeLike

I’m definitely saying Mark Skilton has superceded David Smith. Definitely. Pay attention!

LikeLike

“The second aspect of the real is authenticity of spirit: that’s a sine qua non of any art that really matters. It’s not quite the same as ‘character’. You can have it and lose it, but you can’t lose your character, good or bad.” Alan Gouk 2009. OK — “I contradict myself — so, I contradict myself ” Walt Whitman. Let’s have a heated debate about that one! Actually, I think I was probably right the first time.

LikeLike

Oh please, not the “authenticity” thing…

You know what, you’re right ever time, you are a God. Let’s go sing some Bruce Springsteen.

LikeLike

The concept of “authenticity” is essential to modernism because the question raised by a modernist work is the question of fraudulence. The existence of a tradition is the existence of media that generate instances of the medium, automatically so to speak. A work that obeys the rules of the medium IS an instance of that medium. However, the absence of a coherent tradition is the basic historical fact that created modernism, and its consequence is that we cannot determine a priori what will count as an instance – as a continuation of the art – and therefore the question of authenticity comes to the fore. (Another way to put it is: there is no audience for a modernist work.) And authenticity is a matter of character. In this circumstance, the question of whether the artist’s “character” is unchanging or evolving I think misses the point, which is: in the creation of modernist works, the artist’s credibility is always on the line, because in creating a work that is false or unfelt, the work fails not relatively (e.g., it’s a painting but not a successful one) but absolutely. Why not say that the artist’s character is always to be discovered and manifested in each new work?

LikeLike

Why not just say I’m not creating modernist works? What then?

Where and when did this authenticity/modernism thing start? Cezanne?

How do I know when I’m being “authentic”?

How do you know when I’m being “authentic”?

LikeLike

“Well, this morning I ain’t fighting, tell her I give up

Tell her she wins if she’ll just shut up

But it’s the last time that she’s gonna be riding with me”

The Boss on Abcrit

LikeLiked by 1 person

I hope I am not misreading Alan Gouk again but I do see his point about ‘character’ . I feel that as I am trying to ‘find’ something while working on a painting, I sort of end up finding myself all the time and need to make a conscious effort to change direction in order to bring something new into the work.

The thing is we are all just footnotes now because so much has gone before us, but I can’t understand why Alan Gouk has to be so scathing about the Brancasters.

LikeLike

Well said, Noela, though I think you are underlining my point rather than his – that ones character is mutable, and you have to work at it to get beyond habitual shortcomings and cliched delivery. Key for me is how to get beyond known formats, which, if you are relying on working just quickly and spontaneously, you will fall back upon.

All this highfalutin talk of inner life and unveiling of character is as much use as a chocolate teapot. I’m saying get in the studio and (consciously!) actually make some interesting and down to earth new things happen, and lots of them, and then you stand a chance of getting beyond both yourself and the mannerisms so deeply engrained in much abstract art, as well as all the ideas and limitations in your own head about what abstract art is. You need to get over yourself.

Brancaster Chronicles may well be the continuation of something started long ago, but it undoubtedly also brings something new to the table, in its incredible focus on what is working, and how, in abstract painting and sculpture. OK, it stumbles along in quite a long-winded way to the outsider who can only watch the rather extended films; but for the participants, things are moving fast. The proof is in the pudding, and ALL of the best abstract sculpture and a great deal of the best abstract painting is being made by Brancaster artists today. And it will get even better. Just look at the progress individuals have made.

That’s why, from talking about Matisse’s greatest (?) paintings, and why they might be not so great, and why they might actually slip down the tables of the KEY PAINTINGS OF THE TWENTIETH CENTURY, we go to talking about Brancaster.

LikeLike

I’m generally supportive of Brancaster but the shift from a supportive discussion group to this type of hugely over the top promotional machine is not good.

LikeLike

What I find not good, Sam, is your death-by-trivial-twitterdom of the whole abstract art thing. Each to his own, eh.

LikeLike

To return to the “composition” thing…

I recall a conversation with Alan years ago in his studio, talking about the occasional diagonal that appeared in his work, as opposed to the more frequent “racks” of semi-rectilinear shapes or broadly horizontal stripes. When it came to diagonals, Alan disliked the fact that they left “corners” in the work, to be solved “compositionally”. In other words, the return over and again to some kind of loose “format” allowed Alan to bypass compositional decisions to an extent. And broadly speaking, I can go along with that – except that I think there are possibly better ways to get around the idea of “composing” an abstract painting. These ways might well involve getting inside of how the work is built from absolute scratch, rather than resorting to a known way out. “Composing” implies to me that you know a way or method to an end result. Back to discovered content again – or my version of it.

LikeLike

To answer Robin’s four questions : 1 You can say it, but you’ll be wrong, or else you don’t really mean it.

2 More or less yes.

3 You don’t and can’t

4 That’s the key faculty that observers of modern painting must try to cultivate, and which appears to be in short supply. Carl is right about that. It’s the acid test.

But with Sam, I can’t stomach any more of this grand standing. I’m out.

LikeLike

PS. The disparagement of authenticity is a post-modernist lie. But you “can have it and lose it”.

LikeLike

Excuse me, I’m not disparaging it. But let’s leave it to history (and not your history) to judge who has it and who doesn’t. You cannot judge yourself.

LikeLike

Well, obviously you can, Alan, because you’re above us all. Talk about grandstanding…

LikeLike

I don’t think Brancaster Chronicles has become this ‘over the top promotional machine’ as Sam suggests, it’s just that Robin is very supportive of the concept and the artists involved, what’s wrong with that. Not that many people have heard about the Chronicles even.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think the “objecthood” of bad artworks might be an older phenomenon than Modernism and Michael Fried.

“Get thee hence, and take thy daubèd cloth, and make thereof a housyng for thy swine!” As Shakespeare (might have) said.

Works with no life, no authentic human content, no “magic”, whatever one might want to call it, have surely always been many steps closer to the ultimate objecthood of a place in the dustbin (or the role of historic decor in a country house) than the works that possess these qualities and are therefore retained and cared for and restored over generations.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, but “objecthood” only became an issue or concern internal to art-making when the continued existence of art-making became threatened, that is: when it certain kinds of things were no long NATURALLY accepted as artworks. Another way to put it: objecthood became an issue internal to art-making when judgments of artistic quality seemed to lose their relevance and application, so that the distinction between art and non-art seemed to supplant the distinction between good art and bad art. Duchamp’s read-mades made this phenomenon absolutely explicit. At some point, something was lost in the way Western people experience the world and what was long was not just something but the very sense that something was missing. (By the way, Greenberg’s evaluative (not theoretical) writing contained references to objecthood long before Fried made it a theme.)