Space in Sculpture.

I wish to return to Emyr Williams’ very interesting and thought-provoking article on ‘ Space in Painting and Sculpture’. Not being a practitioner in painting I will confine myself to comments on sculpture space.

To try to define what space in sculpture involves, it is reasonable to suppose that the primary fundamental observation to be made about all sculpture is volumetric displacement; the quantity of actual space occupied by the parts and whole of a sculpture(s); literal air translated into a physical entity. Sculpture shares this quality with all other three-dimensional objects, though we need here only be concerned with an art form such as architecture, or pottery, for example. Following assessment of the volumetric space occupied by a sculpture’s physical ‘thingness’, the means by which this displacement is effected, other than purely literally are pertinent. In pre-20th Century sculpture this was tied primarily to the physiology of the human (or animal) body; its limbs, its connections and junctions and their movements (in space). Even though sculpture is materially static (stone. wood, clay, metal etc.), if attached to this universal subject it energises variation of spatial occupation through implied movement (the liveness of the body), as against simply accepting the whole as a ‘lump’. Even the most monolithic sculptural traditions (Egyptian, Mexican, African) use implied bodily movement to suggest ‘freeing’ the monolith spatially, usually by means of cutting into or through the material. Monolithic sculpture also frequently attempts spatial extension through massing, on an ordered quasi or associational architectural basis (temples, palaces); Easter Island is a good example.

If sculptural form serves an underlying purpose as a recognisable arm or leg or back or foot or breast or buttock, it is simultaneously these things AND a piece of conceived form occupying space and displacing it in a singular fashion, deriving from the force and drive of a sculptural idea. Many old (historical) sculpture traditions were not so tied to recognition as an imperative as not to be able to depart from it when the power of plastic feeling dictated it. Within recent history Rodin, Degas, Matisse, Picasso and one or two others were heavily influenced to some degree by the discovery of these traditions. All four made significant sculpture within the roughly twenty-year period around the turn of the century when this knowledge became available, knowledge of artforms that, at least partially, abandoned the imitative character that Nature’s model would normally impose. ‘Abstraction’ (non-figuration), overturning the spatial expression of bodily gesture to replace it with an attenuated invented version involving the parts of a sculpture being shaped by ‘expressive’ plastic decisions, rather than mimetic ones, now begin to occupy the direction that sculptors in the early 20th Century were taking – penetrating and animating space in ways undirected, or only partially, by any bodily naturalistic model or norm. Rodin’s use of parts to make sculptural conglomerations serves as a pointer to the direction that progressive sculptors were taking.

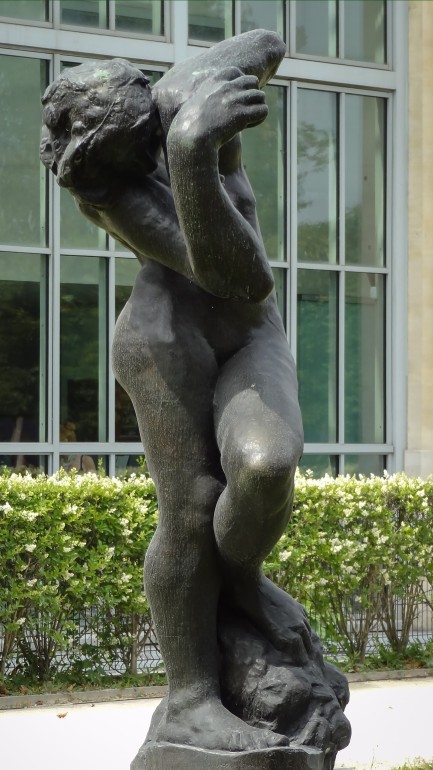

Awareness of space and expanding into and occupying it, as a ‘quantity’, enabled a sculptor to turn with relief from the burden of verisimilitude. If we take, for example, Rodin’s ‘Meditation (with arms)’ in the Musée Rodin, the base of the female figure is comparatively conventionally modelled in a contrapposto pose, whereas the top part from the breasts through to the neck and head and arms is wildly distorted to the point of total reinvention of any real structure; occupying and displacing space in an extraordinary fashion, turning the body into a sort of windmill or signal. This process of seizing space in an unconventional way with conventional form can be found throughout most of Rodin’s work and is followed by similar characteristics in much of Degas’ and Matisse’s sculpture. This vision of invented physical extension into space became the harbinger of much that was to follow; with Gonzalez’, Picasso’s, Chillida’s, David Smith’s work, in metal in particular, serving as chief protagonists. Picasso’s ‘Head of a Woman’ 1929-1930 (painted colander, springs, iron and sheet metal) serves as a good illustration of the new spatial freedom. The idea that material as such, devoid of any attachment to representation, or literal illustration (other than in a quasi-humorous, suggestive way), could substitute spatial activation that previously was only achieved through reproducing Nature’s artifices, opened up a new vision of creating sculptural space as a considered part of a sculptural whole, more powerful than had ever been available in the past. Space begins to be seen as a plastic additive to the composition of a sculpture’s ideated assembly. In addition, shaped material was now not only crafted by the sculptor’s hand, but could include ‘ready-made’ manufactured form in various industrially employed materials, thereby introducing into sculpture types of spatial organization and occupation only previously associated with functional or crafted objects that had no emotional poetic content.

But what of ‘interior’ space, of that created within a sculpture by the new freedoms as well as by occupation? Undoubtedly the main progenitor of this novel path for sculpture, historically concerned primarily with mass and volume, was the advent of ‘construction’, via painterly collage and the willed efforts of Picasso to ‘make’ from his observation of ‘things’. This observation of things became the transformation of things into otherness; a sculptural otherness, that immediately distanced the ‘new’ sculpture from the old, formalized it into ‘non-figuration’, eventually ‘abstraction’, as distinct from ‘figurative’ or representational. Construction permitted the widest use of material(s) as long as it was deemed necessary to the emotional building and plastic conception of the whole sculpture and its parts. This led to the generation of a ‘type’ of sculptural space, ‘interior space’, space entering and exiting the body of the sculpture as a willed necessity whilst at the same time being part of its space ‘occupation’ as mass.

The various experimental ‘schools’ of sculpture-making that developed from around the first world war period onward – Cubism, Constructivism, Surrealism, and so on – served to enlarge and expand on this constructed vocabulary. Picasso’s ‘Guitar’ 1912, Tatlin’s ‘Tower’ 1914(?), Giacometti’s ‘Palace at 4am.’ (193 ?) David Smith’s ‘Australia’ 1956 (?), Reg Butler’s “Unknown Political Prisoner’ 1956(?), illustrate the variety of approaches that were being explored, involving spatial direction and occupations conjoining with a sculpture’s built parts. These conjunctions remained, however, firmly conceived within a comparatively limited format that did not venture out of the bounds of an ‘image’, or accepted notion of ‘wholeness’. Eventually, sculpture began to be digested on much the same terms as any other object; and indeed, in more recent history, was often indistinguishable from one; or, alternatively, was to be confused with ‘architecture’ or ‘engineering’, ’machinery’ or some other three-dimensionally constructed ‘thing’.

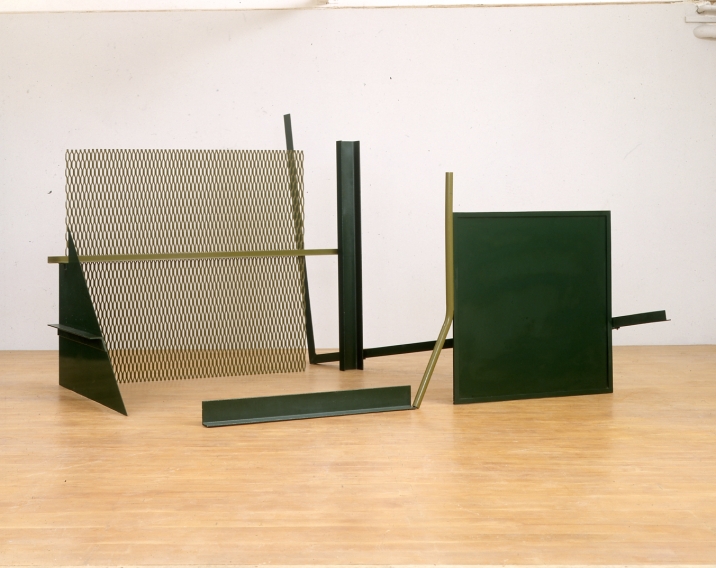

American painting’s example of extending the viewers field of vision beyond what was normally possible in peripheral vision, had a profound influence on sculptors (at least in the Anglo-Saxon world) who realised that they too could attempt to generate a ‘spatial environment’ beyond the field of vision immediately available from a static viewpoint. (Obviously, sculpture had always contained the ability to present multiple viewpoints to the peripatetic stance of the viewer; though, strangely, rarely taken advantage of). And so, we come to Caro’s abandoning of his fifties concerns of a sculpture of volume and mass and limited extensions into space, to attempt a sculpture that would create a context that would dramatically affect space beyond its ‘field of vision’.as had his friends the painters.

This idea of a different spatial context to sculpture than had been explored very much in the past, became known as ‘pictorial’, for its dependence on a planar two dimensional ‘field’ of viewing that eschewed much movement around the sculpture’s literal three-dimensionality, other than to discover similar ‘fields’ where one’s eye could rest. It is also noteworthy that this new form of sculpture embraced the use of colour, whether for purely practical constructional reasons, or something more profound, must be left open to debate and opinion (I myself took it seriously). The fact is that this emphatic ‘pictorial’ context for sculpture’s spatial occupation and manipulation greatly extended the power of the interior ‘space between’ to impress itself on an almost architectural scale. Indeed, the resulting works often more resembled architectural constructions than sculptural ones. Much of this ‘architectural-ness’ (architectonic?) was of course also due to the uninhibited use of industrial material, often unformed by anything other than the manufacturing process, and relying solely on the ‘new ‘context’, into which it had been placed by re-use, to carry the ‘idea’. As already mentioned, these elements carried with them their own form of ‘space’ in the manner in which they occupied it or the manner in which the given form would carry with it a given spatial ‘design’ (‘I’ beams for example). Another aspect of ‘pictorialism’ that tended to impact greatly on the way space was ‘used’ in sculpture was the dominance of the junctions, of part to part relationships as technical connections; only being conceived for practicality, the touch and consequent attachment of one part to another being without any considered three-dimensional effect on the material being used.at that point. This tended to emphasise the ‘graphic’ quality of the spatial decisions; making the forms of the sculpture look as if they were spread out on a flat plane (canvas?) separated only by a blank and non-physically functioning space – the antithesis of the new spatial awareness that was the aim and a conundrum that the very advances that enabled unparalleled spatial extension, broadness and expansion at the same time tended to annul three-dimensional authenticity.

I have frequently pondered on the fact that in the latter half of the 20th Century, with the ubiquitous advent of Duchamp-ism as a progenitor of the future of art, that there has been so little, if any, continuing discourse among most sculptors on what used to fondly be called ‘aesthetics’, It is as if, suddenly, there was no further use for a branch of knowledge that has been confined to the Middle Ages – quaint, but irrelevant to today’s minds. To continue to discuss ‘sculptural space’ within this context seems perverse. What space? What sculpture? All those old passé ideas have little or nothing to do with current concerns; wake up – join today!

“I hate Caro “, said a world-famous sculptor recently. Well, bully for him, but I would hazard a guess that when Mr. X’s efforts are confined to being an historical curiosity, serious sculptors will still be taking Caro seriously. In fact, I suspect that in the latter half of the century, it was less the shenanigans of those purporting to be ‘sculptors’ that diverted attention from the continuing analysis and rethinking of the mechanics of sculpture making, in theory and practice, than dealing with certain major concerns, in just those same practices, overwhelming attention. ‘Pictorialism’ and the example of Caro’s extended architectural space visibly countering the physicality and three-dimensionality of a sculptural construct in favour of its visual presentation (or viewpoint) from particular chosen ‘sides’, led involved sculptors to start to question the premises on which this development depended. By the mid seventies it was apparent that the initial sweep and excitement of the ‘new’ sculpture pioneered by Caro had run its course and was failing to offer a way forward. Sculptors began to question the assumptions of ‘pictorial’ space as a basis for sculptural conception; and its lack of ‘physicality; its lack of concern for the physical expression of forces dictating structure; or the physicality of connections in relation to their function and purpose; or the physicality of the actual material used in relation to its function and position in the sculpture; or the lack of concern for gravity and its governance of physical forces in a sculpture; or the seeming lack of concern for the physical form of the parts of a sculptural whole and the dependence on ‘given’ form; all of these aspects having a direct bearing on the modelling of space in sculpture.

Where the sculpture (its literal parts) ends in literal space, remains, crucially, open to doubt as to where it is going and what for. There is suddenly a visual disjunction between space as conditioned by its relationship with physical matter as a part of the directions and movements of the sculpture, and then not conditioned at all by any control at its extremities, as if falling off a visual precipice. This is not a new problem; in fact, I suspect that one reason underlying the old grouping of sculpture in architectural settings was precisely because the spatial impact of one lone piece could be transformed by repetition and multiplicity, dulling the finiteness of gesture ending in spatial limbo (Easter Island, Karnak).

A rethink of sculpture’s direction was due, involving many developments, taking place in the seventies, eighties, nineties and into the new century, attempting to address the factors mentioned above. It became clear that outstanding issues of the uses of space and its function in sculpture were of prime importance. Re-involving sculpture with its physicality, with the richness and succulence of material, what it does and how it does it, and why; what, indeed, constitutes a ‘sculptural’ structure as compared to any other; effected the realisation that space, both within and without the work, was as vital a ‘material’ as the actual chosen physical matter in use, rather than merely being ’emptiness’ between parts of a structure. A sort of reversal of priorities was necessary, in which space (as matter) was not only what resulted between one part and another, but was also an extension into and out of the physical material of the part(s). Space could act as actual matter, pushing, pulling, stretching, expanding and contracting in like manner, and having consequently as much influence on the shaping of form as plastic decisions in themselves did. Space is no longer to be conceived of as what happens OTHER than the physical forms of the sculpture, but becomes a living, breathing part of it.

With the dead end of “Duchamp-ist’ philosophy and vast quantities of ‘referential sculpture’ ignoring any sort of serious consideration of plastic values and thus going nowhere, progressive sculpture today can refer to a century of spatial development within the art, drawing conclusions accordingly as to what can be significantly developed into new norms, and what rejected as irrelevant. The uses of space in sculpture will undoubtedly be crucial to this pursuit.

Tim.

In my opinion the problem is that only the NEW sculpture can give us the ABSTRACT space that is required.

Because….THREE DIMENSIONALITY / MATERIALITY / CONSTRUCTION / SPACIALITY / CONTENT / PLASTICITY / etc. etc. etc. can be all thought of TOGETHER and in an ideal world at the same time.

In permeating with each other they could become a new truth with real meaning.

Those masters of sculpture ,to whom you refer, did not see the potential in being ABSTRACT as a state of being. That potential could one day possibly make the borrowings of Caro and the contortions of Rodin ridiculous.

LikeLike

Yes, alright Tony, I trust we are all attempting to push abstract sculpture in directions that it has never been before; but in order to do that you have to be aware of which directions it HAS been down before, and, hopefully, experienced a few of them first hand to really know them.

I also think that you have to BUILD on what has been before, even if it means totally rejecting it, which is often the case.

I was hoping you would add some comments on ‘space’ in sculpture as you see it and whether you agree, for example, ,that this is a crucial element in any new thinking.

LikeLike

Tim.

As best as I can I have expressed my view at this moment as to how things like space etc. could benefit by being ‘worked up ‘ together.

I am sure you will say that we are already working like this as it does sound obvious. Maybe it is deemed easier to talk about them as separate things but I do want to think about them and work with them together.

I have put out what I think is happening in what sounds like an idea when in fact it is something which is evolving not fixed.By bringing everything together as much as that may be possible the experience of sculpture may be looser, more fluid and more free. to be clearer we would need illustrations of pieces to talk about. [ as in the Brancaster Chronicles.]

I am sorry I can’t give what I think you want.

We seem to be in a place now that demands being more specific. Can I add to that…..In terms of sculpture making the “elements’ of sculpture seem to be demanding more inter-dependancy.

LikeLike

“Spatiality” sounds like a neologism or a bit of jargon, but it’s much more useful than talking or thinking about generic “space” in or around a sculpture. It applies to the very specific, abstract, three-dimensional and illusionistic properties that are emergent in sculpture right now, when the material and the space are profoundly engaged together in an expressive whole. It’s not a word I feel I can apply to any figurative sculpture that I can think of, past or present – of course they occupy space, but so does a washing machine. In the Rodin, expression is not really spatial; whereas in the new abstract sculpture, spatiality must be engaged with in at least equal measure with the physicality of the material. What is crucial is the freeing of sculptural structure from the literal or metaphorical, and we are only just beginning to really understand that and put all of these things together at once. It’s very much a live project.

Caro’s sculpture seems to me to fall into two camps – the pictorial or the architectural. We can dismiss the former as unspatial without any further explanation, but in the latter, the engagement with architectural space seemed at first to offer something new. I’m sure a good architect will argue (correctly) that in great architecture, space is illusionistic and poetic; but in an “architectural” Caro space seems to me to be passive and almost entirely literal. The whole business of repeating/echoing the walls, floors, doors, whatever, of architecture, and all the associated bodily relations to human scale and physical size etc., as well as the division of space by drawing (as in a Smith) are all literal/semi-figurative/dated ways of working. They were interesting attempts to free abstract sculpture from the figure, but now look like they failed to do exactly that.

“Spatiality” has to go far beyond the occupation, delineation or primitive engagement of space. How the particular spatiality of each individual new sculpture is generated by the articulation of material is fundamental to moving sculpture forward, but it might turn out to be the very thing that truly makes a break, utterly and irrevocably, with all sculpture from the past.

LikeLike

Tony – I would not for one moment wish to, or seem to wish to in my article, diminish the importance of any of the ‘categories’ you mention; I agree that they should all be worked together. I singled our ‘spatiality’ (R).as of specific import as an ingredient of sculpture that has has minimum thought.

Robin – I was a little bit surprised that though I would agree that space both architectural and sculptural must be ‘”poetic” (to succeed expressively), you say that sculptural space (Caro) is literal as against architectural space. I would say that it is the opposite: that sculptural space (good or bad or indifferent sculpture) is by definition illusion i.e. non literal, and that architectural space, whether poetic or not, is by definition literal, i.e. you use it (movement) to define it as well as see it.

.In my article I tried to further the idea that sculptural space can and must become more ‘physical’ and ‘plastic’ in its role in new sculpture, but it will remain the ‘idea’ of those things depending on the intensity of the idea to turn the ‘illusion’ into a sculptural reality.

LikeLike

Robin’s post is a good example of someone using a lot of words, all divorced from their ordinary (and therefore meaningful) usage. Example: “Spatiality” has to go far beyond the occupation, delineation or primitive engagement of space.” This sort of nonsense isn’t new; it’s always been used by those who wish to announce in manifesto-like proclamations “a break, utterly and irrevocably, with all sculpture from the past.”

LikeLike

What is this “ordinary usage” which is meaningful rather than, well, what?

I get the criticism relating to believing one is breaking completely from the past but I see value in ambition and progress whether or not you agree a particular artist is ambitious, progressive, or not. Thinking through the notions of time and temporality is helpful here.

LikeLike

As far as I’m aware, Carl, the use of “spatiality” in discussing sculpture is new, and it has no ordinary usage. When did you last use it in conversation? In fact, my spellcheck continues to question it every time I write it.

As for having a manifesto, my aim is really to just chivvy things along a bit in how we think and talk about sculpture, and to explore the means by which we can address issues. Whether you like it or not (and it appears not) there are some new aspects to progressive sculpture that we are trying to discuss that are looking more pertinent than the stuff Fried put out fifty years ago.

Unlike yourself, my ideas are not fixed; also unlike you, I don’t subscribe to a manifesto written by someone else.

Tim; I’ll stick with my assertion about the space around a Caro being on the whole rather literal, but maybe you should give us an example of expressive space at work in one of his sculptures?

LikeLike

Let’s stick to the one we have ‘The Window 1966 -67’; (I am assuming we have all seen it in the flesh). I would call its space ‘referential’ rather than ‘literal’. I am not apportioning ‘good’ or ‘bad’ to this, merely stating it as a fact (in my eyes). It refers to going in, coming out, going behind etc., rather than actually enabling these things as in architecture. Which is why I say that it is still ‘illusory’ space and not ‘real’ as in architecture (literal) and I would have thought that any sculptural use of space will remain ‘illusory’ in this sense. But, of course, what I wish to see in sculpture now is that ‘unreality” being challenged by new ideas about space. .

LikeLike

Caro’s sculpture “The Window” is not difficult to read as a photograph, as a series of elements standing, leaning, being held, weighting, fixed at strategic points , combining to form a structure that any one who has lived a life out there will understand. It’s proportions are the beautiful thing about it.As a structure and expressed as a structure it is literal, the space of the floor [ not the actual bits which the sculpture sits on but the floor described by the bits ] and the space above the sculpture are ambiguous. The drama of the work or the excitement ,and this will be felt less today than in 1966 but is still significant, is the surprise that this is in an art gallery and is a sculpture, to the viewer .But ,as a structure, this is perfectly understandable and comes in a form that is also understandable.So that brings me to the question Caro asked , “Could this be sculpture ?”

I am happy with “The Window” but I don’t understand what it is going to do for us today.

Space could be seen as a facilitator. It first allows you to have the material seen at all and then it facilitates a judgement of what the material is doing. It then can allow multiple judgements, multiple assessments , multiple feelings of multiple activity in and throughout. It is vital in allowing your eye to know where these activities are as you focus and re-focus. It is an enormous facilitator which you would not want to pin down. It is brilliant and is being explored and expanded in the new sculpture.

In my own sculpture I have brought the activity of material ever closer to its neighbours allowing a greater opportunity to control this material in this ever increasingly rich and demanding space.

LikeLike

“The Window” is surely not spatial, and therefore not using space expressively, because it is not even really three-dimensional, beyond the literal space of the floor that it occupies. It’s frontal too, perhaps derived from Matisse’s “Piano Lesson”, and as much an example of Caro’s pictorialism as his architecturalism. Worst of all worlds: no three-dimensionality, no plastic engagement of the space and the material, nothing really very abstract happening. I have no particular wish to criticise this work, other than to flag up the big difference with the new sculpture, but I would note in passing that a window, along with many other architectural elements, is not a particularly three-dimensional object to reference.

To press the point – and you were asking for a discussion on how spatiality is crucial to the new sculpture – I would say that the spatial illusions in new sculpture are beginning to address the imagination in exciting and real ways WITHOUT resort to metaphor. So, in an imaginative sense, the “going in, coming out, going behind etc.”, to use your example, is (seen to be) happening in the material/space of the work itself, rather than suggestions of literal actions of the viewer’s body to be projected onto the inert space and material of the sculpture.

LikeLike

“I would say that the spatial illusions in new sculpture are beginning to address the imagination in exciting and real ways WITHOUT resort to metaphor…”

Exactly so; I could not have phrased it better.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Tim

What a load of waffle ! My response to art is emotional. I don’t want it explained.

Mae

LikeLike

Yesterday morning I found an email from Love Swans and one from eHarmony (promising me a perfect partner) in my inbox. No doubt they were from the “ideal,” “abstract” world Tony dreams about. I didn’t open them, but I did, of course, open the one from Abcrit linking to Tim’s essay.

I don’t want to make a big deal about Tony’s “ideal world”—but it might be useful to note that The Authorities in New York, while being enthusiastic about “Brancaster sculpture,” do object to a kind of evenness in the work: “THREE DIMENSIONALITY / MATERIALITY / CONSTRUCTION / SPACIALITY / CONTENT / PLASTICITY / etc. etc. etc.” ARE all thought of together, all evenly balanced: nothing is out of line: nothing says, Boo!

I do want to pick up on Tony’s suggestion that the “contortions” of Rodin might one day seem ridiculous. Back in the ‘70s, when I was in Sidney Geist’s sculpture class at the Studio School, I told Sidney that Michelangelo’s figures were a joke: ridiculously muscle-bound, ridiculously contorted. Sidney gently replied that he’d never thought of Michelangelo as a joke. (I was a student.) When I brought up Bill Tucker’s book, and Tucker’s suggestion that Rodin’s The Kiss was a “monster,” Sidney was less gentle. Sidney said he thought Tucker was a monster.

When we look at Rodin’s The Meditation (with arms) in the JPEGs in Tim’s piece, seeing contortion is understandable. A photograph of Rodin’s The Kiss can be “too much.” But what are we missing when we look at photographs? We’re missing SPACE! Just space: (not spatiality). We can’t walk around the sculptures. We can’t move our heads/eyes. A photograph (even the two photographs of The Meditation that Tim generously includes in his piece) cuts off so, so much.

I’m sure Tony has walked around plenty of actual Rodins, but I wonder about whether some of you Brits can look at figure sculpture “abstractly.” Tim doesn’t seem to have any problem with figures. And Robin can, on a good day, look at paintings of figures without fainting. But, Tony, when you walk around The Meditation, do you really see contortion? Doesn’t the contortion you might see in one view somehow dissolve as you walk around the figure, as you experience the whole design? When we talk about a sculpture being “resolved”—beautifully/completely resolved—aren’t we talking about an absence of contortion, an absence of excess? Yet how different The Meditation is from The Kiss. They “say” different things even though they’re both beautifully/completely resolved.

Well, 5 paragraphs and I haven’t said much about Tim’s wonderful, joyful recapitulation of space in modern/contemporary sculpture. Reading the piece, I kept thinking about Tim’s Cathedral and ancient Egyptian relief sculpture. Tim’s Cathedral is kind of horizontal, kind of architectural—and very “simple,” very clear. Maybe to some extent ancient Egyptian relief sculpture shares these characteristics—though of course there are a couple of things different about it too. Ancient Egyptian relief sculpture is “old” (NOT “new”) for one thing. And there’s a sense in which you can think of there being constraints on the Egyptians’ engagement with space—but I wonder: were they not just as (if not more) wild and crazy (and abstract) about space us “modern”/“contemporary” folks?

I remember reading an essay of Alan Gouk’s in which he said relief sculpture is NOT something in between “3-dimensional”/in-the-round sculpture and “2-dimensional” drawing or painting. He said that was a misunderstanding of relief sculpture, but he didn’t say what was a proper way to understand it.

I was interested in Tim’s mention of Easter Island in his essay. Am hoping he might develop these thoughts. The great American novelist Joseph McElroy visited Easter Island recently. He Tweeted this (with a picture of some big Easter Island heads): “Easter Island. Seas ever leveling. Planet imagination rising. Water Book final section.” (Joe’s written a book about water. Hasn’t been published yet. Great excerpts can be found on the internet though.)

LikeLike

Where is the window in The Window?

LikeLike

Perhaps it’s the window of opportunity to see it only from the front? What does it look like from the side/back?

LikeLike

Tony – “Space could be seen as a facilitator…” is spot on; an inspired use of the word ! It is comments like these that make these discussions worthwhile.

Jock – As it happens, I have actually been to Easter Island. It is an extraordinary place; extraordinary because it is 5000 miles in ANY direction before landfall, and extraordinary because it is the only place I have ever experienced where sculpture was the most important thing in people’s lives. Quite why they were so obsessed is still a mystery (among many others), mostly to do with the logistics of making and moving huge sculptures around the island. The island was once fully forested and there exists along with the well known volcanic rock sculptures a tradition of small carved wood sculpture rather Melanesian like.

I was rather surprised to learn that Sydney Geist was rude about Bill Tucker; as I recall. Bill thought a great deal of Geist

One of the tests that I have always thought exposes really good sculpture from the rest is that it is impossible to photograph. We are all too familiar with dinky photographic ‘views’ of sculpture being taken for the real thing, thus losing any sense of the REALITY (and all that that implies) of sculpture.

LikeLike

Tim.

Not sure about your take on photography re.sculpture.

Loads of sculpture gives us structure, form and space well within the range of our experience.[You only see what you know !]

Sculptures of the figure would be the obvious start point, a field day for the camera but not necessarily promoting the meaning of the sculpture.The hidden figurative associations of Caro’s sculpture slots into this for me ,and is also very at home in the cleared gallery space, inside, not outside, echoing the space of the gallery.The sculpture and the gallery are now in a self supporting relationship. In fact you are made to feel that the architecture of ‘the white cube’ is incomplete without the sculpture.So what I am suggesting is this is a big ‘assist’ to any meaning the sculpture may have.

By comparison today’s sculpture can go anywhere because it lives in its own world, in its own space.

LikeLike

Tony – Yes I accept your point about the bits we KNOW in a photograph being available thereby as real sculptural experience; but what about the bits we don’t know ? A photograph presents them as an image; as a two dimensional silhouette. not being capable of giving any sort of three dimensional plastic experience. I would perhaps qualify this a little by saying that it applies more the more complex the piece is; and that very simple pieces come out best in photography which automatically selects a viewpoint. (Caros are particularly prone to this). It is an interesting point as to whether figurative sculpture suffers more or less than non figurative works from photography’s presentation.?

I also think your suggestion that presentation space (galleries) can and does affect.the ‘meaning’ of a sculpture, (though I think we are into dangerous Conceptualist ground

here ?); .and I assume you do not think it is at all desirable as an aim. My own view about my aims in my own work is that photography will render them almost impossible to ‘get’, sadly..

LikeLike

Tony,

As far as I am concerned, your last sentence – “today’s sculpture can go anywhere because it lives in its own world, in its own space” – applies to just about any good art: paintings, sculpture, novels, music. If it’s good, the content will convince as a total and believable world of its own, transcending any context. And indeed, as I’ve said many times on Abcrit, poor art relies on contextualising to gain significance and a literal or literary meaning, whether it be physical (the gallery), cultural (the interpretation) or historical.

With the advent of late modernism and Post-modernism, context has come to play a greater and greater part in the minds of both the artist and their public. An early example is installation art or site-specific art, where the context is a prime necessity. And Caro is on record as saying he was one of the first installation artists.

LikeLike

Tim, many thanks for your notes on Easter Island!

About Sidney and Bill. I’m sure Bill still does think highly of Sidney. Sidney had plenty of respect for Bill. BUT Bill was “rude” about Rodin (than which there is no greater sin!)—and Sidney had a very sharp tongue. I’ve heard Bill has almost completely rewritten his Language of Sculpture book for a Chinese translation. I bet the bit about The Kiss being monstrous is gone. What’s interesting to me is that I still remember that class with Sidney vividly. When I was 25, I knew EVERYTHING there was to know about sculpture. Then I went to the Studio School, to Sidney’s sculpture class. In so many ways I’ve (very happily) never left the Studio School. I first heard Tony’s quip (“You only see what you know”) in one of Garth Evans’s sculpture classes. Garth is still working hard to maintain some coherence in sculpture at the Studio School. In a crit a few months back Garth admitted he knew nothing about sculpture. What do we know about sculpture? How do we get past what we know? How do we learn? Is rudeness the only way? (I just looked up the word “rude.” It means impolite/ill-mannered, but also primitive, crude, rudimentary, rough, simple, basic.) These are questions only Carl Kandutsch can answer.

LikeLike

How do we get past what we know? Make abstract sculpture, mate!

LikeLike

Every time you start a new sculpture you have to TRY ti get past what you know already;; difficult, usually fails, but necessary.

LikeLike

This is what I think at the moment [ I think ]

It used to be easy to talk about sculpture with a strong ‘storyline’ ‘Window’ being a good example.

The sculpture we are now trying to talk about that desires three dimensionality and fluidity with no prescribed views, can only be worked on ‘imaginatively’. To put it all together as a whole may be beyond traditional ideas of comprehension. You do not walk around a piece to learn about the whole in quite the same way. The space is in a way everything else put together. On its own the Material is, incident. Movements come and go, rhythms evolve. The space may be the constant that gives the whole as ever changing and only ever seen as a variable in time, but imaginatively as that whole.The things that you know not being of this moment would block and disrupt this imaginative juggling.

So, because of the desire for three dimensionality, you feel the need to forget what you know, as Tim says,and replace it with invention of some kind of new continuity in time.

LikeLike

To give Caro his due, you did get an extemporised way of working, which perhaps was some kind of seed for this spontaneous way of looking and thinking about the totality of sculpture as being of a different order of things from ordinary objects. By contrast, some of the New Generation stuff like the Annesleys that Sam writes about are restricted to being two-dimensional designs for manufactured objects.

LikeLike

“Caro’s sculpture seems to me to fall into two camps – the pictorial or the architectural. We can dismiss the former as unspatial without any further explanation, but in the latter, the engagement with architectural space seemed at first to offer something new. I’m sure a good architect will argue (correctly) that in great architecture, space is illusionistic and poetic; but in an “architectural” Caro space seems to me to be passive and almost entirely literal. The whole business of repeating/echoing the walls, floors, doors, whatever, of architecture, and all the associated bodily relations to human scale and physical size etc., as well as the division of space by drawing (as in a Smith) are all literal/semi-figurative/dated ways of working. They were interesting attempts to free abstract sculpture from the figure, but now look like they failed to do exactly that.”

This entire paragraph is complete nonsense, mostly because it mistakenly assumes that “spatial” is somehow a property of objects in the world, like size or color or shape or mass, whereas in fact, spatiality refers to one component of what allows human beings to exist in a world that includes objects (that have certain properties like size, color, shape, mass, etc.) For this reason, the concept of space can never be divorced from “associated bodily relations to human scale and physical size” – unless we’re talking about physics or scientific measurement or some other realm of human activity that has nothing to do with making art.

Caro’s Deep Body Blue, for example, is a sculpture that engages with space in a most profound way, and it does so by claiming space in an abstract rather than a literal way. The sculpture does not “repeat/echo” (whatever that might mean, I have no idea) doors, but rather makes the viewer aware of his or her own spatiality, or more accurately, the spatiality of the world in which we actually live – which is a world in which we – because we are embodied beings rather than pure spirits – approach things that are near or far, bump into things (like walls and barriers), avoid things, withdraw from things, pass through things (like doors and other entrances), run away from things, encounter things, and so on, all of those being modes of being in the world that are, always have been and always will be (for as long as there are human beings) addressed in art.

To say that Deep Body Blue (an arbitrary example, since there are literally hundreds of other works by the astoundingly prolific genius Caro that illustrate the same approach) uses space in a way that is “passive and almost entirely literal” is just not to see the sculpture at all. A sculpted door, a representation of a door in sculpture, would presumably occupy space in a passive and literal way as does an ordinary door, which we can find at the home décor store. But, of course, that’s exactly what Caro did NOT do. Instead he made a work that invites the viewer to contemplate (and contemplation of art always involves feeling at least as much as intellection) human spatiality, which is the only spatiality there is, phenomenologically speaking. This required that the sculpture overcome, by suspending, our tendency to treat objects like doors as literal objects; it required him to make a sculpture that is radically unlike anything we actually encounter in the world, which is why Deep Body Blue is an exemplary abstract sculpture and a masterpiece that by its mere existence mocks puerile put-downs like this one: “They were interesting attempts to free abstract sculpture from the figure, but now look like they failed to do exactly that.”

LikeLike

We are obviously never going to agree on this, Carl; but the reason I proposed the word “spatiality” in the first place is to distinguish an illusionistic and imaginative property that a sculpture may aspire to which transcends the normal conditions of literal space as it engages with being properly “abstract” – which for me is a condition of three-dimensional visual wholeness and relatedness rather than a metaphysical state. It is an aspiration that I stand or fall by, just as I stand by my opinion that Caro seldom if ever got beyond first base in terms of spatial articulation of material. And whilst his jump from lumpen figuration into open “architectural” mode was startlingly fresh in the sixties, it is pretty certain that he never in his long career was able to engage his material in a close conjunction with space in a way that – rightly or wrongly – progressive sculptors are now attempting and succeeding to do. Time will be the judge of our efforts. Your strong support and love of Caro’s work and Fried’s interpretation of it is something that to some degree I can respect, even though I think it is outrageously excessive and skewed; but in any case, as things stand going forward, it is irrelevant.

LikeLike

“We are obviously never going to agree on this, Carl; but the reason I proposed the word “spatiality” in the first place is to distinguish an illusionistic and imaginative property that a sculpture may aspire to which transcends the normal conditions of literal space as it engages with being properly “abstract” – which for me is a condition of three-dimensional visual wholeness and relatedness rather than a metaphysical state. It is an aspiration that I stand or fall by, just as I stand by my opinion that Caro seldom if ever got beyond first base in terms of spatial articulation of material. And whilst his jump from lumpen figuration into open “architectural” mode was startlingly fresh in the sixties, it is pretty certain that he never in his long career was able to engage his material in a close conjunction with space in a way that – rightly or wrongly – progressive sculptors are now attempting and succeeding to do. Time will be the judge of our efforts. Your strong support and love of Caro’s work and Fried’s interpretation of it is something that to some degree I can respect, even though I think it is outrageously excessive and skewed; but in any case, as things stand going forward, it is irrelevant.”

The word “spatiality” has been widely and profoundly (to use spatial metaphors) explored in modern philosophy for 260 years, since Kant wrote the Critique of Pure Reason. He was the first to notice that “space” and “spatiality” are not qualities that can be attribute to objects, but rather ways (along with temporality) in which human experience is necessarily organized in order that there can be such a thing as a “world” that “contains” objects. Since Kant’s time, phenomenology has continued this exploration. In light of all this history, talk about “new spatiality” seems bizarre to me, like “new humanity”, etc. I always distrust this sort of rhetoric, and it seems to me that your idea of a work of art being “spatial” or “not spatial” is hopelessly retrograde and basically meaningless.

Anthony Caro’s work demonstrates a deep intuitive understanding of our contemporary understanding of space as a constituent of the human world in which we exist. To describe those works as “figurative” on the ground that they implicitly address concerns that are native to human beings (as opposed to, say, aliens from another galaxy) is just absurd. For example, to say that a sculpture that deals with “verticality” as “figurative” is idiotic. Human beings stand erect; a human being stands or walks or lies on a horizontal plane and rises up, but not very far; when a human being uses his or her eyes, he or she can survey a horizon; the horizon is distant, or it may be obstructed by barriers; we encounter things that are proximate or far away or recede or approach; we pass through entrances and we are inside or outside of enclosed spaces like rooms. If you think that the “new spatiality” can somehow “transcend” these limitations – which are also ways in which the world is revealed to and discovered by human beings – you’re deluded, and more importantly, pointlessly deluded. Would you prefer to live in a “new” kind of space that is not relevant to human beings? Feel free to do that, but it won’t be a space that is pertinent to art or life, because art that doesn’t deal with what it’s like to be a human being existing for an indescribably short instant in a limitless universe of nothingness – isn’t art at all.

LikeLike

This is a response to your comments on Kant further on in comment section on primordial spatiality. I wrote this piece about the famous Davos encounter between Cassirer and Heidegger in 1929. I gathered from the several books on that meeting Heidegger was trying understand the a priori of the human experience in Kant whether it is finitude or the kind of primordial space that is more important than any new kind of space based on scientific and mathematical notions of space.http://martinmugar.blogspot.com/2017/12/ideas-matter-1929-davos-debate-and.html

Some commenters who were there at the meeting of the minds felt that there was no possibility of communication between the two as they used incompatible vocabularies. Maybe that is what is going on here in this discussion.

LikeLike

The Caro window piece seems to be a pure expression of the Humpty Dumpty effect,where once things are taken apart they can’t be put back together again.It is a modernist trope and fits in nicely with everything modern. It has no space and is just parts that don’t work as a whole. Seems to be a period piece. http://martinmugar.blogspot.com/2012/01/humpty-dumpty-effectonce-veneer-of.html

LikeLike

Carl – good to have you commenting on sculpture rather than semantics !

“…the CONCEPT of space can never be divorced from…”

I was trying, in my essay, to comment on the USE of space (in sculpture) rather than its coincept..My point was to show that, in the past, especially in ‘modern’ sculpture, it has rather been taken for granted (as a physical attribute of sculpture), or ignored, or treated in an architectural or pictorial, rather than any specifically sculptural manner, and that this has changed in the minds of progressive sculptors) to being seen as something that can be used, be manipulated, just as material is manipulated.

Existing examples of the putting into practice of these ideas may well be thin on the ground at the moment, but undoubtedly the will is there.

Re: Caro; I would state firmly that none of us would be where we are if it was not for his example.

.

LikeLike

Thank you Tim for responding to the my article on Space. I enjoyed reading the article and agree with all your points – the references are part of my own understanding of Art so were familiar to me. I do not have the same debt to Caro being a painter, however I can acknowledge his significant contribution to the development of sculpture. He did at times lapse into making eye candy works but so what? I didn’t know him as well as you, but he was generous and encouraging about my work on a number of occasions. I wonder if the architectural element of his work – for me!- has something to do with the horizontal of the floor – only ; the sheets, flats, openings I am not that concerned with as “architectural / architectonic” – it’s just that horizontal plane and its consistency throughout a lot of the work that I ‘muse” over to myself from time to time.

I think movement is pivotal in how space works. How our eyes move. Often just the handling of a surface for me makes my eyes work, how a colour “breathes” is a form of movement-sensation. Space can occur in a painting through simple colour relationships. Though this space can be compromised or maximised dependent on how these relationships are seen. The same colours – in the same place can be totally different dependent on how they got there and their respective facture appearance. Some people can deliver a line ( no pun intended), swing a golf club, ride a horse and so on and it just looks different to the same thing done by another. Simple but incredibly complex.

In certain Japanese swimming pools there is a chemical added to the water which reacts with urine to produce a red cloud around the offending – highly shamed and embarrassed – swimmer. I wonder if there was a gas that could be added to the air around a sculpture which did the same sort of thing for the “active” space. This way we could see which work was good and which work was..piss poor!

LikeLike

Glad you got something from it Emyr.

Re movement in sculprure, I have often quoted the Rilke / Rodin statement on the camera lying because it only captures one moment in,time; whereas sculptural invention can through infinite changes of form suggest the reality (truth) of actual movement.

Re your point about Caro’s horizonral bias, could it be that horizontality has a more ‘abstract’ feel to it; verticality auromatically sounding echos of figuration? David Smith’s work is often a good example of this tendancy. The flat plane of the floor is less ‘suggestive’ of anything; less referential than vertical stance.

Your Japanese swimming pool is highly amusing. Given the amount of cretinous ‘sculpture’ around, I certainly wish a ‘quality’ gas was available !

LikeLike

“Re your point about Caro’s horizonral bias, could it be that horizontality has a more ‘abstract’ feel to it; verticality auromatically sounding echos of figuration? David Smith’s work is often a good example of this tendancy. The flat plane of the floor is less ‘suggestive’ of anything; less referential than vertical stance.”

In ordinary experience, we think of the human figure as standing up vertically or lying down on the floor or some other horizontal surface. We take that for granted, it’s an assumption that we don’t question – and that’s why the floor has the character of literalness. In a traditional figurative sculpture, the floor has no sculptural significance, which is why the pedestal was necessary, to separate the sculpture from the ordinary world in which we live.

In eliminating the pedestal, Caro challenged our assumptions about the floor. Although he wasn’t the first sculptor to dispense with the pedestal, he was the first to give sculptural significance to the horizontal plane on which the sculpture rests, most clearly and beautifully in works made in Bennington, VT, and then in works like “Prairie” and many others around that time, which deploy not only the vertical and the horizontal but the diagonal, which is both and neither. In those works, the floor loses its literal character as the ground from which everything rises, and becomes virtually incorporated into the sculpture itself, as a plane that does not itself require grounding in something else. In other words, the ground is experienced abstractly rather than literally.

I have noticed that in the tendency to disparage Caro’s work (e.g., as either “pictorial” or “architectural” – carefully and tendentiously omitting “sculptural”, as if only the “new abstract sculpture”, having cast Caro’s influence aside as retrograde, is capable of achieving the “sculptural”, or true “spatiality” and “three dimensionality”) doesn’t address his early table sculptures, where Caro’s innovations with sculptural space are almost impossible to miss (although I’m sure some here will manage to miss it as well, because for them, judgment is not based on actual experience but rather the requirements of doctrine).

In the table sculptures, Caro’s task (per Fried’s discussion) was to make sculptures that secure their scale abstractly rather than by way of their literal size (as objects). He did this primarily by incorporating handles or hand implements into the work, and by running part of the sculpture below the plane of the table on which the sculpture rests – which precluded the possibility of imaginatively transposing the sculpture to the ground. By precluding that option, precluded the possibility of seeing the sculpture’s smallness as a contingent or literal fact (e.g., as a small version of something larger, like a model), so that the scale (like the tabletop) is experienced as an essential component of the work, a qualitative rather than a quantitative fact. In so doing, the table sculptures render the idea of scale itself abstract, so that the work is seen neither as big nor as small according to our ordinary criteria, which are grounded in the human figure (being approximately 6 feet tall, etc.).

LikeLike

I am mindful in this debate about Space of the relationship of sculpture to the conditions of horizontal and vertical.

Both Moore and Caro tended towards horizontality. This ‘ state of being ‘ tends towards looking down on something or, at best, across it . A large part of the action is hugging the floor and often a large part of the sculpture shielded from view. So, put simply, the spatiality of the sculpture is shared with the floor. Could’ shared’ be extended as a condition to being absorbed by the floor ?

Surely the origins of the horizontal and vertical are figurative and the reclining figure has always had to battle with its structural energy being lost to the floor. The vertical on the other hand, whilst avoiding this when translated into abstract sculpture,becomes flat and veers towards the pictorial in Smith and Caro , either as something tantamount to a figure , or spreading out as flatness. In either form spatiality is diminished.

The obvious contradiction to this for me is found in David Sweet’s brilliant description of ‘ Early One Morning ” making a case for its seven floor contacts and their variety of influence on the whole.I mention this because I had previously seen ‘Early One Morning ‘ being an architectural space.

The driver to find an alternative to these conditions of horizontality and verticality is this unsatisfying spatiality which hangs around them both.

I have been wondering why Tim bringing this up a has been so difficult for me to comment on when most of the conditions of sculpture can quickly be seen as having a too dominant and restrictive hold on spatiality almost solving sculptures and bringing them to solutions too early. So which comes first, spatiality or three dimensionality ?

Recently sculpture has been referred to as a ‘ lump ‘, a suitably hideous term for a transient condition whilst reaching for a new condition and not an amalgam of horizontal and vertical.

Whist I do not have an answer for my question I think it has been a long held view that the condition of horizontal and vertical is too involved in solving `Abstract sculptures.

That then begs another question ,how Abstract are these the conditions ?

LikeLike

where is David Sweet’s piece on Early One Morning?

LikeLike

Speaking as someone who was obsessed with horizontality for quite a few years, thinking that it was the more abstract way to deal with the “spreading out” of space in sculpture, the idea is bound up in my mind with having to find literal ways to structure the work, including using the floor as structure – which is what many Caros, by necessity, do (Carl’s ideas on this notwithstanding).

It seems to me that the new kind of spatiality is now imaginatively detached from the ‘representation’ by the material of both human horizontality and verticality. It’s as though the sculptural material can now, so to speak, think for itself about what it does, and as such has no necessity to privilege references to human physicality, including our stance (vertical) and our movement in the world (horizontal). Once these kind-of-figurative pre-conditions fall away, the sculptural material can engage with space any-which-way it chooses.

I would further suggest that though spatial issues now seem axiomatic to our thinking about abstract sculpture, there will be within this new spatiality potentially a whole variety of approaches. I note with interest Tony’s previous reference to space as a ‘facilitator’, giving ‘room’ to the material to do its stuff of extreme articulation in three-dimensions. That is EXACTLY what I see happening in his new work. At the moment, in my new work, I feel I am coming at the thing from the other direction – using material to enable the organisation or ‘orchestration’ of the space. I’m sure Tim has his own take on this. Suddenly the debate about space becomes really interesting and complex, way beyond the scope of ‘architectural’ notions.

LikeLike

I keep on meaning to put up a proper response to Tim’s piece. For now could I point out that your hanging sculptures, which seem to me to be much freer than the floor pieces, involve a vertical – the chain – which is as straight as anything in Caro. They also spread horizontally against this vertical, and even if they don’t do this so simply and clearly, perhaps their freedom to move, and the visual strength with which they do, draws on the vertical. This is not meant as a ‘gotcha’, but I do think things are not as clear as this comment suggests.

LikeLike

“It seems to me that the new kind of spatiality is now imaginatively detached from the ‘representation’ by the material of both human horizontality and verticality. It’s as though the sculptural material can now, so to speak, think for itself about what it does, and as such has no necessity to privilege references to human physicality, including our stance (vertical) and our movement in the world (horizontal). Once these kind-of-figurative pre-conditions fall away, the sculptural material can engage with space any-which-way it chooses.”

This reads like a description of an animated cartoon show on TV, with cute little animals flying around, finally free of “references to human physicality, including our stance (vertical) and our movement in the world (horizontal)”, with “kind of figurative pre-conditions” like gravity “falling away” so that the little animal “can engage with space any-which-way it chooses.” (But even Wiley Coyote, after running past the edge of the cliff in pursuit of Road Runner, eventually loses his forward motion and plummets earthward, just a few seconds before he’s crushed by the boulder in a small cloud of dust.)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks to Tim Scott for this essay which gives a clear and concise view of the story of modern sculpture, how its character was transformed by the injection of exotic influences that would differentiate it from the sculpture of the past and how a cycle of change and rejection has brought it to an exciting point where it can be argued that sculpture has demonstrably entered territory that is not reliant on the triggering of figurative or metaphorical reading of its content.

The historical problem for abstract sculptors was that unlike their figurative counterparts they had no recognisable vehicle for expressive intent. It should therefore hardly be surprising that the work of even the most highly regarded and influential of sculptors such as Caro and Smith which had radical abstract intent (at least in the context of their time), can be seen to have fallen short of 21st century abstract goals. However, in relation to Caro Tony Smart makes the really significant point that the showing of works such as ‘Early One Morning’ and ‘Window’ in the 1960’s offered a new vision for the character of sculpture as an object, a vision of clean-lined, open, imaginative structure.

Moving to the present day, the ‘use’ of space is seen as a key consideration for a new, more fully three-dimensional and abstract sculptural experience but I share Carl’s misgivings about seeing space as a commodity that can be manipulated and used as one might use tangible material. Use/manipulation suggests (at least to me) a pro-active exploitation or designing of space rather than having an intuitive and flexible response as to how the sculpture might be developed as an object that can both incorporate space and exist with strong presence IN space.

LikeLike

Marisse said (in relation to his drawing) that he was always conscious of the vertical and horizontal ( of the paper).

ii is a priori a condition of life that we should be thus conscious, as it is a fundamental part of our being,which, initially, is created by the force of gravity on Earth.

In (Tony’s / Robin’s) descriptions of a ‘new’ spatiality it is implied that gravitational force will no longer have any paramount role. I cannot see that this is possible since whatever physical form a spatally conditioned sculpture takes, it will be subject to this force as its physicality, three dimensionality, movement and so on, are conditioned by it unequivocally.As Matisse implies you cannot escape it and its effects.

Sculpture can only escape trom REFERENCE to those things it gets lumbered with; architecturalness, ,pictorialness, two dimensionality, figurativeness, etc., etc.but not gravity.which is inherent in its being.

Is this what we call abstract ?

To come to Terry’s point concerning his misgivings about space seen as a ‘commodity’; I would only say that it cannot of course be a literal commodity, but its EFFECTS, through imaginative illusion, on material, can be FELT with the eyes..

LikeLike

The issue of gravity is something that has been raised numerous times before and I agree with Tim’s take on it. We can see the reaction to and against the vertical and horizontal that other forces / spaces have. The relation to one things defines another. I come to movement as being the important driver of spaces. Our eyes constant shifting (and being shifted) from one thing to another – be it a form or a colour or any change of condition. This movement is where the expression lies. How it gets there is a moot point- as Terry remarks. Even with the most ambitious of intentions this will not guarantee that the result will provide a greater visual experience than works made with very different ambitions. However you set your stall out, you have to maximise your way of doing things first. Someone’s work may not be any influence at all on you yourself, but you must take on board the level of expressiveness that is being garnered in it. I still think abstract painting – for me -is the biggest challenge but I still respect and feel challenged by figurative art when it is really good or for that matter, abstract art that is massively different to my own. Everyone wants to make good art, I feel there is more to it that this as I said but that in itself is meaningless until the work shows it in the strongest possible terms. David Smith and Caro are often chided for their pictoriality but their work still arrests my attention for sure. What, specifically, I am getting out of their work, for example will ultimately remain a personal issue that feeds my own work – as will any number of other artworks through time. There is no need to throw the baby out with the bath water (even if the water is pink at times…)

LikeLike

Tim,

The thing about drawing makes sense if you are working inside the rectangle of a piece of paper. But why should sculpture be thought of as operating inside a rectangle? Unless, that is, you take floors walls and ceilings as its context. Well, I think we have dealt with that already.

And as for gravity – yes, of course, everything we make is subject to gravity in a literal sense (including all sculpture, hanging or floor-based, and even including paintings!), but there is absolutely no need to make gravity a central focus to the imaginative content of the work. Not only does the pursuit of full three-dimensionality rule out thinking orthogonally, in verticals and horizontals, but the search for a properly abstract and sculptural structure, as against literal structure OR ITS METAPHORS, means that an emphasis on how the work makes reference to its condition under gravity might well be sidelined.

Regarding Sam’s comment – I agree, things are never clear cut, and I would concur that hanging a sculpture has its own limiting factors. Nevertheless, the direction of travel in these works is towards a freer three-dimensional content than has been attempted in sculpture before. I would maintain it is a more three-dimensional and more abstract approach than Caro. Whether it ends up being better or worse as art is not something I can answer.

LikeLike

I don’t see it as a limiting factor – apart from in sense that all art has limiting factors (or is that just wooly?)

LikeLike

“It”, the hanging, is not a limiting factor in itself, and was embarked upon to get round some of the limiting factors inherent in standing on the floor. But hanging gives rise to some limitations of its own – for example, the sculpture HAS to find a (literal) balance on the end of the hook. The important thing is thinking about sculpture differently. I’m working now back on the floor, having changed the way I think because of making hanging sculptures.

LikeLike

What is absolutely fundamental to me – more fundamental than gravity! – is attempting to work out what sculptural structure might be AS OPPOSED TO literal structure.

I think it is a mistake to try to hold all sculpture to account by invoking the laws of physics – or for that matter, the conditions of architecture. For a start, to say that “…whatever physical form a spatially conditioned sculpture takes, it will be subject to this force as its physicality, three dimensionality, movement and so on, are conditioned by it unequivocally” does not deal with the nature of the sculpture’s content, only (again) its literal context. It’s a bit like saying (random example) that Fra Bartolommeo cannot invoke the effects of light on an Italian hillside using pen and ink, due to his drawing consisting literally of black marks on white paper. And as surely as Bartolommeo DOES invoke those specific effects of light (without, I might rather gratuitously add, referencing the vertical and horizontal in the drawing I have in mind), surely it is right and proper that the content of sculpture has the freedom to transcend those impositions of literal gravity that attempt to limit it. Why not? If artists want to deal with gravity, fine. But if not, why not? I don’t see my work becoming esoteric and unphysical just because the content does not address gravity directly. I do see it moving into unexplored sculptural territory.

And in any case, the laws of physics are not what they were. They are no longer based upon Newtonian ideas about billiard balls bouncing off each other. New thinking in physics is wildly counter-intuitive. All is up in the air.

LikeLike

Carl,

Re your last comment above:

No-one is going back to making stuff like Caro, not now, not ever. Despite the fact that you think he made several thousand masterpieces. Now THAT IS deluded.

Tell me Carl, as regards the fabulous “Deep Body Blue” (for example), just what am I supposed to look at in order to discover something interesting or exciting or involving or moving or “human” In this work? Point it out to me. What did Caro really put into this work? Where does the material engage with space? Where does the sculpture engage with the eye? Where does the content engage with the intelligence? I’ll tell you – nowhere at all. Describe what is happening in the sculpture – actually IN THE SCULPTURE – not literally, but as a sculpture. I know you can’t because it’s a banal arrangement of boring bits of steel. Only context, physical and cultural, can make anything out of this, because basically it is a content-free piece of vacuous minimalism. You can’t say anything real about it, and what’s more even Fried can’t say anything real about it (I’ve just re-read his paragraph on it in your Abcrit essay and it’s eyewash). You and he can only frantically contextualise and philosophise about it, nothing else – apart perhaps from the ridiculous and contradictory notion of an “abstract door”. Not so much an example of “deep intuitive understanding”, more a bit of a sad laugh.

LikeLike

I did not for one minute, Robin, imagine that the Matisse quote should be taken at face value for sculptors. It is interesting that a painter (not subject to gravity !?) should feel it in his blood nonetheless. Maybe it was because he was a sculptor too ?

I was wondering when the dreaded word ‘content’ would crop up again in the discussion. The problem is that we all ‘know ‘ what it means, but are unable to describe it. Of course in these discussions we are only attempting to describe the mechanics of sculpture; how this or that might or might not succeed in doing something which in our minds has been forecast, but not yet put into practice.to the point where , yes, its content blows the senses.

You don’t have to ‘deal’ with gravity – it deals with you.

Where I am

LikeLike

Where I am completely of like mind with your comment is on the subject of a sculptural structure. I agree, and have said many times in the recent past, that a rethink on this is absolutely crucial to the evolution of a new sculpture; All the other factors that have come up for discussion are party to this aim in my view; and by structure I mean differentiating clearly from other known structures.of the world. The theme of my essay was primarily that the use of space (your spatiality) would be crucial to this aim.

LikeLike

Yes, well, the word “content” is not dreaded to me, though, because in such a discussion as this it becomes a necessity to distinguish what goes on in a sculpture intrinsically, and what is extrinsic. Or, to put it another way, to distinguish between what the artist puts in (consciously or not, it doesn’t matter) and what culture, circumstances or commentators apply to it after the fact. We can have goes at describing it specifically, as we do sometimes in Brancaster, but yes it’s difficult – quite rightly, because it’s visual not literal or literary. In fact, talking about “sculptural structure” is probably the same thing as content.

So what do we mean? Can abstract content be free-form and free of metaphor, but still have human significance? It’s such a great ambition…

LikeLike

Tim

You say”…. you do not have to deal with gravity it deals with you”. “Gravity is inherent in sculpture’s being”.

Hilde in Brancaster Chronicle 2 says that it is important how energy coming into a sculpture resists gravity.

There have been long discussions over the five years of the Chronicles about the space of the sculpture being part of your space, for and against.

ILLUSION. Sculpture does not do anything or it would not were it not for illusion.

Sculpture that sits in our space and shares its activity with us in the same space, takes on that literalness of that space where things really happen, perhaps becoming figurative

To be Abstract somehow the sculpture must be in its own space. So the illusion of the sculpture is freed from the literalness of real space leaving the sculpture free to explore its “Own-ness’.

Its reality is not competing with the viewer, the ‘actual’ of the body is separated from the illusion of the sculpture.

Does Painting, figurative and abstract, achieves a similar condition via the picture plane?

The free standing figurative sculpture standing in our space begins to look very weird, because the illusion and the known-ness of the body facing our body are in contradiction.

Without its own space the illusion contradicts its aim for the Abstract and returns it to the real world….

I think there may be something in this.

LikeLike

When you have to resort to quantum mechanics you have lost the argument.

On the one hand you are exaggerating the extent to which Caro’s 1962-72 works are “pictorial”. (For a more objective assessment see my Steel Sculpture 1 on Abstractcritical). On the other you are underestimating the extent to which these works engage with and articulate spatial experience. The fact that we have legs and bodies and need to walk around these sculptures to fully take them in and “grasp” their “syntax” does not make their engagement with space “literal”.

And as long as we do have legs and bodies we will remain subject to gravity, and so will Sculpture.

The idea that sculpture is cocooned in its own illusionistic space takes it back close to the despised opticality of yore. Illusionistic elements are consonant with physicality and engendered through physical means.

Sculptural structure is indeed synonymous with content, but it is not antithetical to physical structure, but realised through it. There is a dialogue there which finally resolves itself in the constructed work.

This prejudice against Caro, and the attempt to separate yourselves from his achievement, (even allowing for his many faults in his post 1972 works) only goes to show how great an influence he once exerted on your development. But the critique has become a blindness. Deep Body Blue is easy to dismiss, but I would never single it out as an example of Caro at his best. (See Steel Sculpture 1.)

LikeLike

And as I have tried to show on previous occasions, even in music the articulation of sound structures has a physical dimension, is a physical reality, (See Daniel Barenboim’s masterclasses on the Beethoven piano sonatas no’s 109 And 110 on YouTube), such that its relations to structures in the real world outside music is more than mere analogy, and certainly much more than metaphorical. So if structures in music are physically real, how much more so are the articulated structures of sculpture, and painting. Three dimensionality as an aim cannot be made to override all other considerations, not least the feeling that the work has a conVincing physicality.

LikeLike

Yes but you miss the point. What are the “articulated structures of sculpture”? You don’t know, so don’t pretend you do. A “convincing physicality” of what, exactly?

I have no wish to make unphysical sculpture – and I am not – but the quest for greater and greater elucidation of three-dimensionality and spatiality will be the things, above all else, that will, in my opinion, unlock new ways of making such structures. Really, Alan, what other path is open to us?

I can recall for years and years, certainly with Sculpture from the Body and before, and continuing up until the first years of Brancaster, discussing the concept of “set-up” or “configuration” and how it manifests itself in specific sculptural arrangements. That sort of discussion has pretty much died out in recent Brancaster talks, as the sculpture works its way past literal or metaphoric structure and starts to really challenge what we know about objects and how sculpture might find a very different place in the world. There are still problems – and the polemic against Caro is a symptom of that difficulty – in making and in discussing it, but we ain’t going back.

“And as long as we do have legs and bodies we will remain subject to gravity, and so will Sculpture.” you say. But the body is not the whole person (nor is it abstract), and our imaginations are not subject to gravity.

LikeLike

Robin

An excellent response.

I would add that nothing is off limits for discussion. I know of no document that can replace these open debates.

LikeLike

Thanks.

I have a suggestion – let’s stop talking about Caro altogether. Whatever dues were owed, if any were, let’s assume they are paid. Let’s move on. He is now undoubtedly irrelevant to what is happening, and it is unquestionable that something new is afoot in sculpture. No doubt at all.

How about it, Tim? Can we leave TC behind?

LikeLike

I’m not being asked, but: No, Robin, you can’t leave TC behind. You can stop “talking” about him. You can declare him “irrelevant”—but you’re stuck with him. You’re stuck with gravity too. Why run away from who you are? There’s a nice “profile” of an American sculptor named Sanford Biggers in the current New Yorker. Maybe Caro is “irrelevant” to Biggers—but maybe not: maybe Biggers is saying a lot about Caro.

LikeLike

Well it’s Tim’s article, that’s why I’m asking him.

Biggers has nothing to do with anything. Why not say why we should stick with Caro if you want to make that point. Stop bullshitting, Jock. I’m not running from anything. Look at my work, look at my commitment, look at how I’m facing up full on to the new problems of making abstract sculpture without Caroesque cliches. Then look at your own work and tell me whose running away. Cheeky bugger.

LikeLike

Why do you say Biggers has nothing to do with anything? I guess because you don’t see him as an abstract sculptor facing the “new” problems. But doesn’t that to some extent call into question the “new” problems—even the idea of abstract sculpture? I’m not trying to say Biggers has this special insight that makes the “new” problems/abstract sculpture ridiculous/not worth facing/whatever. Just that Biggers/a quick read of that profile does make me look at things a little differently. Small things CAN—don’t always/don’t often, but can—make big “differences.”