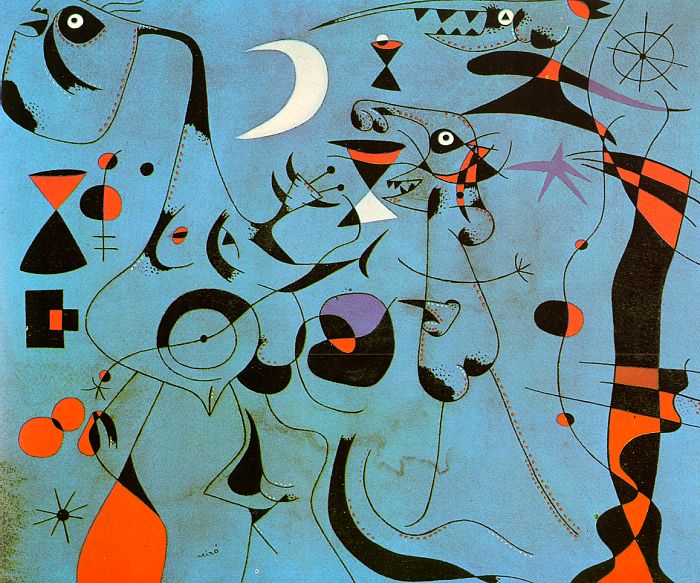

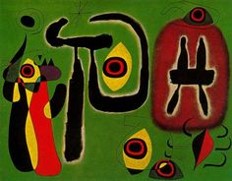

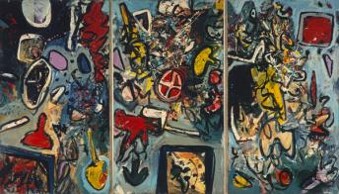

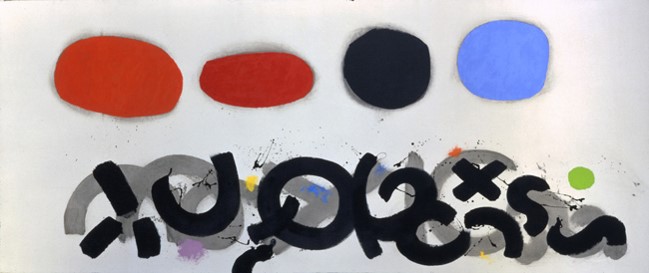

Joan Miro, “Painting”, 1953, Guggenheim NY, © 2018 Successió Miró Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York ADAGP, Paris

“First the Giants, then the pygmies.” Elie Faure

PART 2

Notes Synthetiques ca. 1888 by Paul Gauguin: “Art is an abstraction; derive this abstraction from nature whilst dreaming before it, and think more of the creation which will result than of nature”.

To Schuffeneker Aug. 1888: “Like music it acts on the soul through the intermediary of the senses. Harmonious colours respond to the harmonies of sounds”.

And in Diverse Choses 1898: “ The impressionists… heed only the eye and neglect the mysterious centres of thought”.

The sources of these ideas, which were to prove so fertile for the development of abstract painting, lay in the literature of early German Romanticism, Jean Paul, E T A Hoffmann, the synaesthesic imagery taken up by Baudelaire, Schopenhauer’s views on music as reinterpreted by Wagner, and the cult of Richard Wagner in France, which influenced even the young Cézanne, and the symbolist poets gathered around Mallarme (though some of these pronouncements of Gauguin antecede his friendship with the latter).

Wagner’s music, especially in The Ring, could be described as the triumph of bad literature over music, or the subjugation of music to the literary imagination. The idea that colour, like music, can express the “mysterious centres of thought” appeals to the literary minded, so it is not surprising to find it echoed in Baudelaire and Mallarme. (See the poem Les Phares by Baudelaire). It is for the most part foreign to the French line in painting stemming from Delacroix and finding its culmination in Matisse. Although Matisse echoes the Mallarmean aesthetic “to paint not the thing but the emotion that it arouses in the artist”, in practice his art remains wedded to the full lustre of the sensory world. The transpositions of colour, red for blue, black for azure, are less emotionally driven as arising from his discoveries in Luxe, Calme et Volupte, 1904/05, that degrees of saturation of hue can form the tonal structure, rather than oppositions of dark and light, just as simultaneous contrasts of colour create light rather than oppositions or gradations of warm and cool.

George Seurat and the theorist Charles Henry voiced similar ideas about the expressive role of line and colour in conveying emotion, on the analogy with music, independently of their function in representation. Chromoluminisme as practiced by Seurat and Divisionism as practiced by Paul Signac, endeavour to combine this emotive theory with the science of colour, a hyper-realism, the two sitting uneasily together, and with mixed results, Pissarro being one of the first to express disillusionment with both the pictorial outcome and the intellectual distancing inherent in the approach.

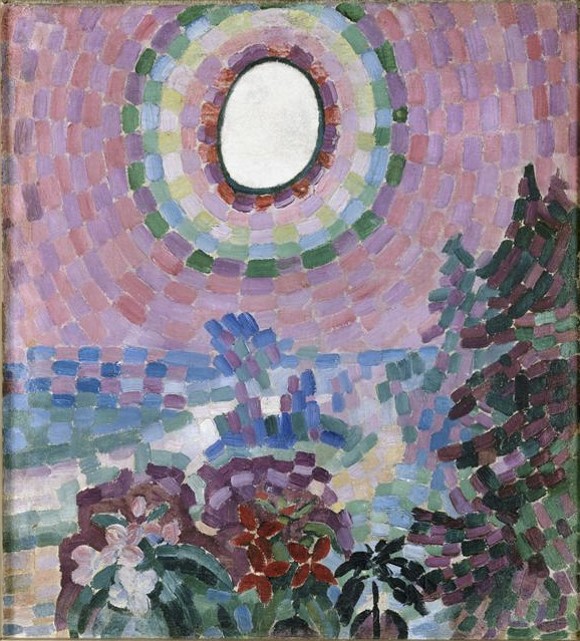

A digression on Robert and Sonia Delaunay:

Robert Delaunay seems to have been given to strident theorising full of abstruse rhetoric about colour and light, making extravagant claims for the revolutionary import of his art. It might be truer to say that Apollinaire was the main culprit, before a rancorous falling out between them. In this they echoed the Modernist proclivity for issuing manifestos – Marinetti and the Futurists, who influenced the hymning of the wonders of technology, Malevich, Wyndham Lewis, Stockhausen, Boulez, Beuys, and many another. (Best to let others do it for you, if you must.)

The first use of the term “pure Abstraction”, akin to music and without a source in nature, is owed to Apollinaire’s proselytising. (It was much in the air as an idea at the time, the 1910s, having been mooted by Frantisek Kupka, a Czech, even before his arrival in Paris.) I suspect that it was Apollinaire’s desire to place himself at the head of yet another revolutionary art movement, as he had done with the Salon cubists, with whom Braque and Picasso never actually exhibited, that led to the rift with Delaunay. The hymning of a vaulting modernity inspired by technology would hit the buffers during the course of the 1st World War, giving rise to the despair and nihilism which spawned Dadaism. Apollinaire received a head wound in battle in 1915, and never recovered, dying of influenza in 1918. Nothing dates a painting more than the worship of technology, since technological change is so rapid that old technology looks merely quaint in time.

The Delaunays seem not to have realised the full potential of their innovations in Abstraction until much later, when their ideas were taken up by others, notably the American Abstract Artists group, founded in the 1930s, and until after Mondrian’s arrival in America, where he began to experiment with colour himself, in Broadway Boogie Woogie, 1942 and Victory Boogie Woogie, 1944. Despite Apollinaire’s advocacy, after 1913-14 Delaunay and Kupka did not pursue the idea of a “pure Abstraction” with rigour, if at all, preferring to explore the expressive potential of simultaneity in colour relationships in a way which drew them back to figuration. A more rigorous engagement with “pure Abstraction” was left to Mondrian, but this involved the suppression of the space-making properties of colour, entrapping primary colour of minimal sensuosity within a prison of black bars, and a commitment to a radical “flatness”. And since colour is the main preoccupation of this Musée imaginaire, Mondrian will be less prominent than other painters who may be have been influenced by him.

Delaunay’s theorising is an intellectualised gloss on the colour discoveries of Matisse’s fauvism of a decade earlier, which had also grown out of a period of experiment with neo-Impressionism. But compared to the mature fauvism of Matisse, Delaunay’s colour is rather dowdy and unvibrant. Relating colour by simultaneous contrast of opposites does not in itself produce vibrancy. The tones need to be carefully adjusted to one another to dispel op-flicker which bleaches out contrasts (as in op-art). When Matisse said that a square metre of green is greener than a square centimetre of green, he was voicing an implicit criticism of divisionist practices, having absorbed and then rejected the style.

Delaunay and his wife Sonia Terk ( it is difficult to separate their contributions to the paintings of the 1910s) attempted to dovetail neo-impressionist colour theory with cubist passage and facetting, leading to a prismatic fragmentation of form over a linear scaffold. It is best to ignore the theorising and just attend to the evidence of the paintings themselves, since the way colour is related in them owes little to the theory.

Coloured pigments do not behave the way spectral light does when fused together. Blue and red light combine to create violet, but blue and red pigments, even when overlaid in transparent layers, do not, but rather produce a murky brownish black. The Delaunays tend to avoid this by placing simultaneous contrasts side-by-side in accordance with classic neo-impressionist principles, or else interspaced with adjacent hues on the spectrum.

Simultaneity, or simultanism, became the watchword, and it has been very influential on later colourists. But it is not the colour contrasts themselves that induce the sensation of movement they sought, so much as the arcs and whorls of curvilinear drawing with which they disposed their colours.

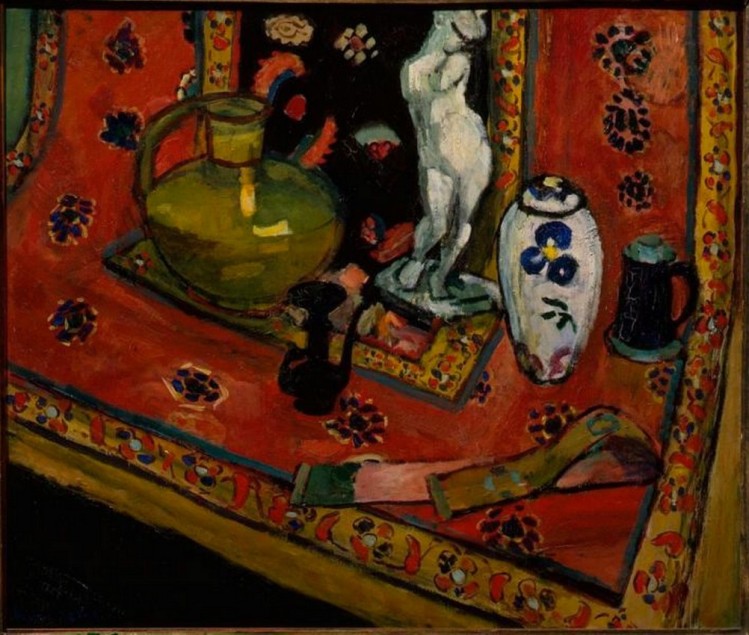

Simultaneity and transparency together influence the Windows and Prismes of 1912-13. The aim was to imitate the effect of light through stained glass, by rendering the paint semi-transparent, but this is a figurative conception. Transparency is all very well, but strongly saturated colour has more visual impact. Matisse does not depict effects of light in his still lifes of 1905-10. There is a close identification of coloured substances in objects or fabrics, surfaces, and the impregnating of the surface of the canvas itself. This was a purely intuitive discovery initially, and it leads to the greater vibrancy of colour and stronger form in these great still lifes. When colour is closely identified with the physical surface on which it is spread, that is the path to Abstraction, even though it was in these figurative paintings that the discovery was made. The task for abstract painting is to rival the formal and colouristically strength of the Matisses.

Of the two Delaunays, Sonia seems to have been the more gifted painter. Robert’s colour is vitiated by an unhappy blend of pseudo-science, mysticism emanating from Apollinaire’s flights of fancy, and naturalistic thinking, and a surfeit of ideas incapable of pictorial realisation. But his obsession with colour as the fount and origin of painting, and his preoccupation with the image of the sun, symmetrical, haloed, brightly pulsing, would lead to a reappraisal of his achievement in the 1940s and 1950s, resonating with the colour experimentation of Josef Albers at Black Mountain College, and through him on the young Kenneth Noland.

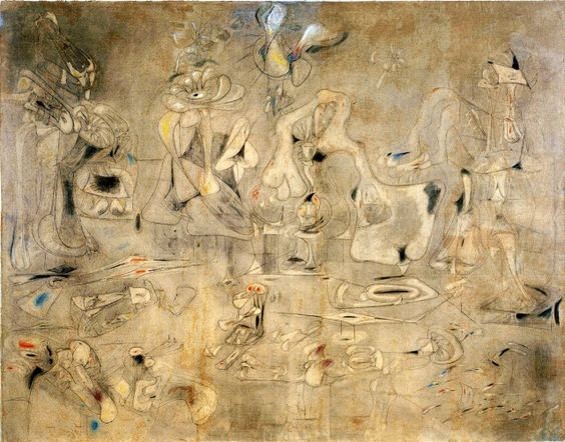

Clement Greenberg , in a throwaway remark, said that one day it will have to be explained how anti-Stalinism became art-for-art’s sake. He might equally well have asked how the anti-art subversive pranks of the Dadaists and Surrealists were transformed to become fertile material for the imaginations of true painters like Arshile Gorky. The most important influences to shape the art of both Gorky and Pollock were Picasso, during the phase of surrealist terribilita, leading to the Guernica studies, and Miro, whose innovations are also influenced by surrealist practices.

Joan Miro, “Painting”, 1953, Guggenheim NY, © 2018 Successió Miró Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York ADAGP, Paris

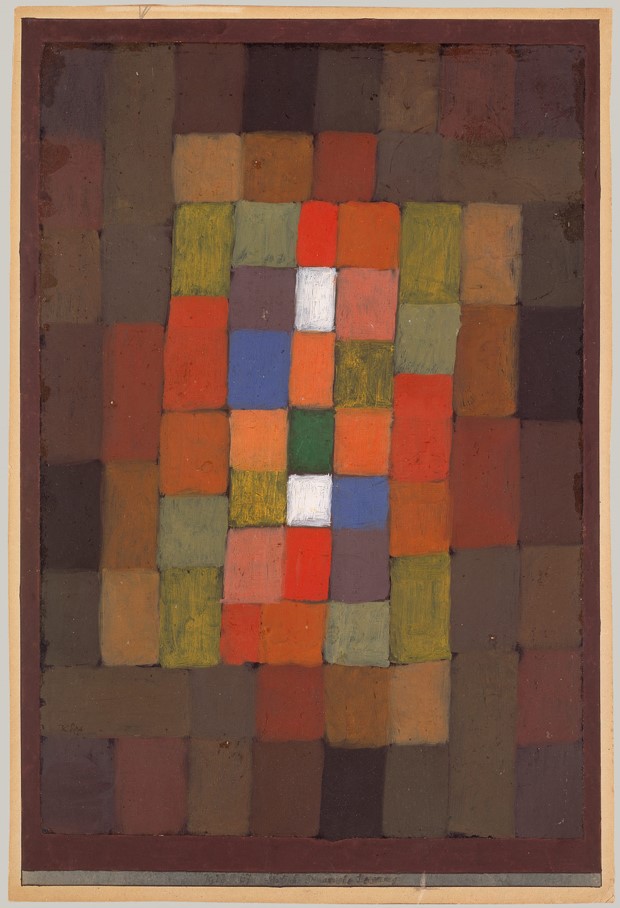

However, there is nothing essential in Miro that is not pre-figured in Paul Klee. If one wants to understand the origins and impulses which led to abstraction, one needs to look elsewhere than the relatively extravert orientation to the external world of Matisse, Braque and Picasso. One needs to engage with the visionary imagination, the inner world of German Romanticism as it emerges in the art of Paul Klee. The fact is one can’t really understand the origins of abstraction and it’s motivating impulses without realising that, contrary to the Greenbergian thesis, positivism and materialism are not the key characteristics of modernism. And the strain of modernism that issues from Klee, Kandinsky and Mondrian is opposed to these very tendencies in modern psychology, perhaps because they are the dominant modes of action and perception. Their art is visionary, inward, and a curious blend of spiritualism and science.

Klee and Miro open up a seam of imagination even further removed from the norms of Western European art than Matisse. Miro takes Klee’s calligraphy and broadens and enlarges the feeling with a greater impulsiveness of attack, and he follows him in experimenting with the expressive range of granular grounds, different media, types of paint quality, from transparent grainy washes to viscous pourings and droplets, opening up for the eye, as never before envisaged, the timbre and texture of paint and surfaces in themselves, with their fictive potential suppressed. (An equivalent of Schoenberg’s Klangfarbe.)

To see how much more abstract Miro is than Picasso, see this installation shot of their two pictures side by side. Clement Greenberg, in perhaps his greatest piece of critical writing, described the difference between Picasso and Klee thus: “ The difference is that he (Picasso) sees the picture as a wall, while Klee sees it as a page”. Miro bridges that gap.

“L’espoir nous revient par la fuite des constellations” by Joan Miro (L) and “Femme assise dans un fauteuil” by Pablo Picasso

Paul Klee is less naturalistic in his thinking than the Delaunays. As early as 1903, at the very outset of his career, he wrote: “For visual art never begins with a poetic mood or idea but with building one of several figures, with harmonising a few colours and tones or with calculating spatial relationships etc. And whether an idea then, belonging to that other extraneous area, joins in or not, is completely irrelevant : It may do, but it doesn’t have to.” And later: “To paint well is simply this: to put the right colour in the right place”. Through the Bauhaus, Kandinsky introduced Klee to the Delaunays in 1912, and their Simultaneous Windows, or Prismes Electriques influenced Klee for an instant before his sojourn in Tunisia. Klee’s colour has greater luminosity even when employing browns and greys far from the contrasts available from the spectral wheel alone. His colour is richer, less naturalistic in implication, and more abstract (with reservations).

Robert Delaunay, “Windows Open Simultaneously 1st Part, 3rd Motif”, The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice, 1976

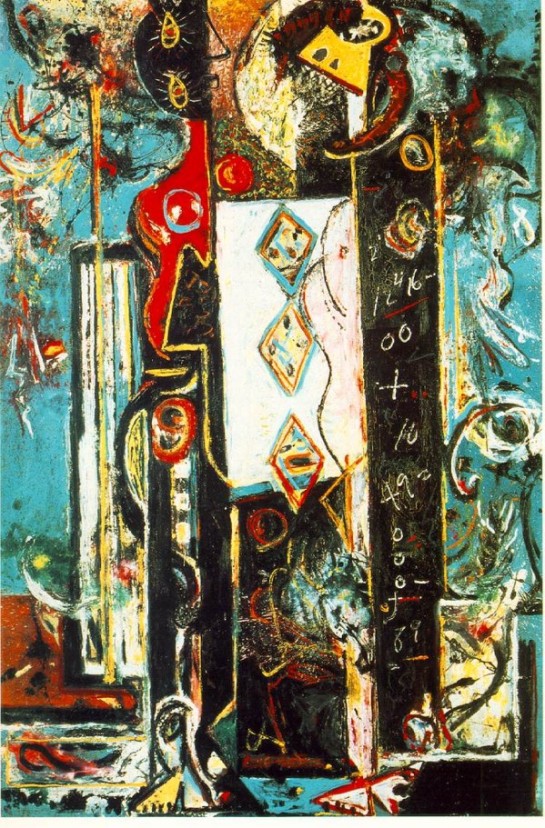

The one positive outcome of Marcel Duchamp’s otherwise poisonous legacy was the Love – Machine, diagrams of the human reproductive system at the point of coition seen as a metaphor for creative conception. This image which first appeared in some of Duchamp’s studies for the Large glass was taken up by others, Masson, Matta, and thence in the brilliant drawings of Gorky and in his paintings of the late 1940s, where it is combined with the opening up of the expressive potential of the surface itself we have seen in Miro. The Liver is the Cock’s Comb is his masterpiece. Eros, juissance, fertilisation, pollination, form a continuum, the life force of Gorky’s pictorial imagination, with its corollary, a movement towards the death instinct.

Although all the main elements of these stylisations can be traced to other artists, including early Kandinsky, (see Sketch for Composition II and Deluge Improvisation 1913), Roberto Matta chiefly (but Matta is a cartoonist compared to Gorky: see The Mirror of Memory , IVAM Valencia.), Gorky is not an illustrator. He does not project an image into fictive space as Matta does. He has learned from Miro that the surface is an expressive force in its own right, as are the varied properties of the medium itself, if used sensitively. And the brilliant suppleness and eloquence of his line drawing is in a different class from the flashy cartoonish art of Matta, (shades of Pixar). Lee Krasner was right to reject his art as insufficiently “plastic” in conception.

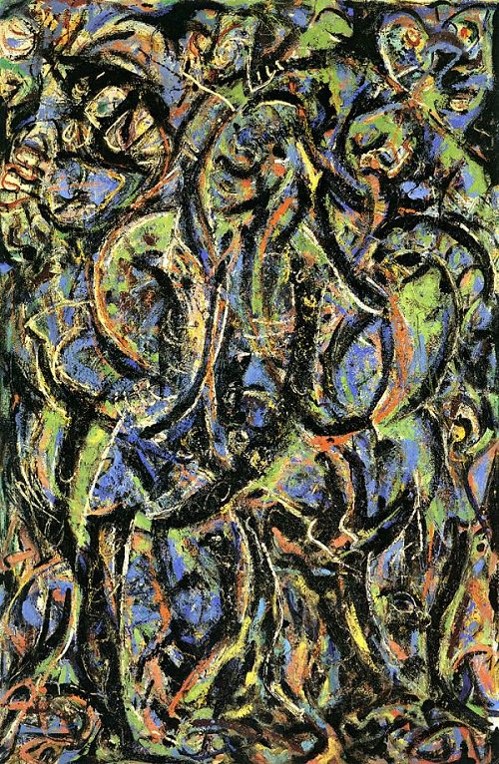

Jackson Pollock could never be satisfied with the belle peinture and the finesse of Gorky’s appropriations from Miro, nor Miro’s wit and humour. He was obsessed with the violence of expression in Picasso’s studies for Guernica, and The Dream and Lie of Franco, an art that seemed to answer to the violence of the times. Guernica was the most newsworthy public statement in purview. Pollock wanted to make a similar statement with that degree of historical import and currency, but his own obsessional imagery was too personal, too private and conflicted to form the basis of a public statement on such a scale. Although the level of ambition, the competitiveness, is generally a good thing, and raised Pollock above his peers, there is the corollary that bad art attempts to coerce, to twist our arm with its currency and relevance.

Mural, 1943, gave Pollock the opportunity for such a major statement, which had been rehearsed to some extent by collaborating on the murals of Orozco and the W.P.A. projects, but never with this degree of subjectivity. The myth that it was painted in one night of frenzied activity has been discounted by conservationists, who have shown that there is substantial revision carried out over a number of days, as one would expect. Its somewhat coarse and hurried attack is compensated by the breadth and vigour of its imagery.

The importance of this painting not only for Pollock’s development, but for American painting as a whole cannot be overemphasised. It’s daring, the courage to risk all to impulse, on the throw of the dice, and accept the consequences – not in every painting, but to have that potential within you, and the courage to go with it when the occasion demands – largeness of vision, generosity of spirit – this is what I mean – this is where I stand; art need not exhibit struggle, work, laborious integration, it can exult in the freedom to be simple, and to express that freedom in a bold statement. That is what painters since have taken from Pollock’s example, though he struggled to repeat the achievement until the great Lucifer 1947, One 1950 , and Autumn Rhythm 1950, paintings which are the envy of every ambitious painter since.

Of course, just like everything else in life, once realised, it can become a cliche, this freedom, a recipe; but none-the-less it still stands as lodestar of one aspect of great painting, and fired the imagination of many artists in its wake at a particular moment in history.

What is originality, and where does it spring from? How does it arise, since it is plain that technical expertise and knowledge of the past will not suffice? It is invariably the result of synthesis, but it doesn’t happen overnight without extensive rehearsal and preparation. And it is possible to be too knowledgeable, and about all the wrong things. The phoney avant-garde took off from a remark of Pollock’s – that “technics is a result of a need” – confusing the idea of technics with new technology, and in America with the tendency to think that artists are “inventors” rather than creators. (Cage, Harry Partch, Conlon Nancarrow etc). “Freedom” is no substitute for rhythmic vitality and compositional originality, using the full resources of the medium. But it cannot be forced or willed into existence. Freedom contained and controlled by a powerful plastic impulse, in other words a sense of form, issuing in abundance, abandon even – that is what reaps the biggest rewards. “Where there is no constraint there is no tension” (Stravinsky).

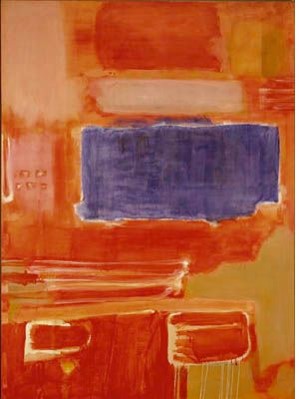

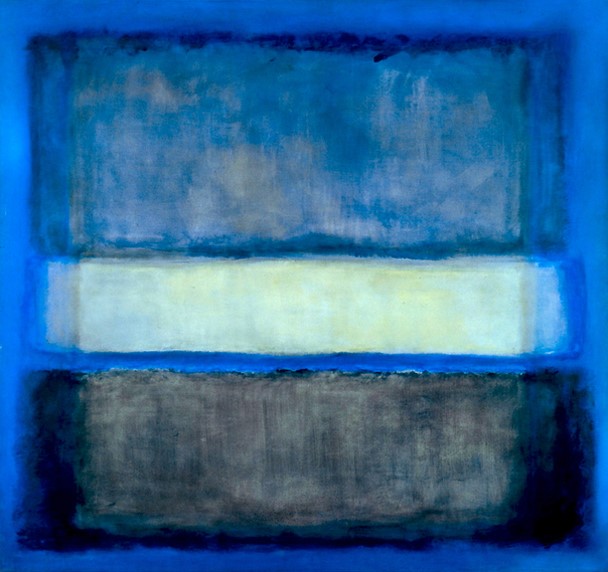

This sequence traces Rothko’s progress from semi-figurative surrealist imagery to abstraction. I have said elsewhere that the influence of Milton Avery can be detected in these pictures, but it is clear also that the sensibility at work has affinity with the “inspired timidity” of Bonnard. It just goes to show how far timidity can take you when it comes to the orchestration of colour. Rothko’s colour is rare, in that acute psychological distress is conveyed through colour contrasts normally associated with hedonism. Pink in the context of red can be searing in the right hands, just as Picasso can place pinks and violets in a context which renders them nightmarish. It is the way Rothko works up his surfaces and edges, with fuzzy nuanced transitions minimising the physicality of surface and paint that creates a fusion of gravitas with delicacy of feeling. Giving a zone of colour an aureole or halo of lighter colour at its perimeter, tends to suggest a numinous dimension to its feeling, as in a Russian icon. This would seem to be the world of feeling in which Rothko lived and moved, in his art at least, however incongruously it sits with his lived environment. And that this is the way he wished his art to be seen is signalled within the paintings as well as by many comments he made about them, before going silent about his intentions in later life. Gottlieb employed similar devices to quite different effect. I set aside T.J.Clark’s attribution of “gaudy” to Rothko’s colour, as simply the usual scurrilous philistine attempt to diminish abstraction’s power to move, by associating it with its opposite.

Patrick Heron’s seminal review of the first showing of the Abstract Expressionists in London in 1956 at the Tate Gallery singles out Rothko for especial praise, while raising doubts about the others, and there is no doubt, despite his protestations to the contrary, that this show marked a decisive shift in his art towards abstraction, and Rothko in particular, though he rapidly turned the influence in the direction of a more European sensibility, less nuanced, a more immediate and direct attack, and an asymmetric compositional style more akin to the early Multiforms , which Heron insists he had not seen. Soon he was able to say –” there is one continent left for painting to explore, in the direction of colour, and in no other direction” (paraphrasing).

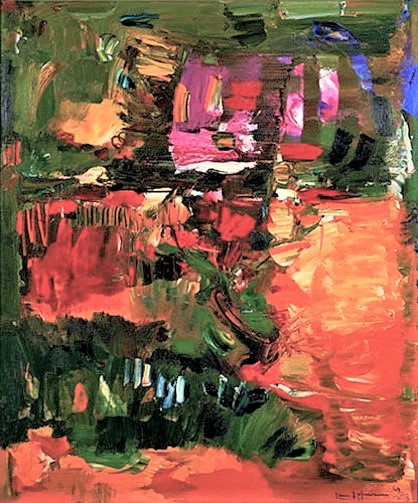

But Heron’s painting in the “utter directness” of its fauvism (and on the cusp of abstraction, but with a representational edge) has marked similarities with the fulsome attack of Hofmann in the mid-fifties – Radiant Space, for example.

Hofmann’s art is an actualisation of the Germanic tradition of painterly painting as defined by Heinrich Wolfflin. “An impulse into the depth is answered by an equal echo out of the depth…. Impulse and echo establish two-dimensionality with an added dimension of created breathing depth”. (Hofmann)

The American critic and painter Darby Bannard has coined the designation “the trampoline effect” of the sort of space generated in those Hofmanns which bounce blocks of colour off transparent washes – the brilliant colour play where some blocks sink in, while others project, as seen at the maximum in the great Goliath, and also in In Sober Ecstasy, shown recently at the R.A.

But I remember talking to Heron after the Hofmann retrospective at the Tate in 1988; these were precisely the qualities that Heron found offensive – the sudden abrupt jumping from “background” to “foreground”, and the sharp edges and corners of the blocks which stuck out like sore thumbs.

Heron favoured a more continuous surface, equally present in all its parts “…of equal intensity, clear, demarcated, out there, resistant to the eye” (Adrian Stokes). He abhorred background, figure-ground painting. The trampoline effect is a speciality of Hofmann, an extreme instance of his “push and pull” dynamic. But there are other, gentler ways of achieving “depth” in abstract painting.

Although the trajectory of his style is from a fauve/cubist hybrid figuration to an expressive Abstraction which exploits the fundamental pictorial elements akin to that of Klee and Miro, Hofmann, with his training as a scientist and his intellectual acuity, is well aware that Abstraction is a relative condition, forever subject to mediation by the visionary imagination of painterly inspiration, and a give-and-take with the sensory world outside painting. A strict or severe abstraction that is subject to prohibitions on the free use of colour as the agent of space, as in the line of descent from Mondrian of the 1930s, and geometric Abstraction in general, will inevitably result in an impoverished art in some direction or another. Hence the wide range of Hofmann’s exploring of painterly means (always subject to the disciplines of the picture plane), and what some regard as the profligacy of his multi-styled approach. But this is precisely why his art has been so influential on a younger group of painters in this country. He closes down nothing, and opens up possibilities for others.

Hofmann is a synthesiser, born a year earlier than Picasso. Through the power of his fauvist colour he transforms the schematic rudiments of geometry in the earlier pioneers of Abstraction, Malevich and Van Doesburg, into something more dynamic and spatially active, at times monumental in its architecture. His paintings have an objective presence which far exceeds his predecessors in that genre.

To the extent that a painting evinces a coherent formal structure, it will tend toward a rhyming correspondence with structures outside painting, more than mere analogy, and much more than metaphor, but always falling short of coaxing the viewer into a naturalistic reading of pictorial space. In the end the painting should “ stand intact as a created independent object,” a work of plastic art. Simultaneity, transparency of colour, and “push and pull”, the reciprocal pressure of saturated hues, employing the full range of contrast of which the means is capable, all of this is in play in Hofmann’s oeuvre.

The De Stael problem.

The De Stael problem concerns the distribution of dark and light, and the way these are organised to depict the fall of light striking the surface of planes inflected towards and away from the eye; planes stacked so as to induce a sense of volumetric recession, as if a sculpture of a body is bathed in light. In De Stael the light is depicted as striking these surfaces from a source outside the painting, and so his pictures are not truly “abstract”. And this depicted volume of the figure, since it is flattened to adjust to the plane of the picture in broad planes which do not, or almost do not, attempt trompe l’oeil, cannot cohere into a convincing whole. But it is a matter of structural vision and of degree, of emphasis, not an absolute barrier to formal coherence. However it is not often realised that this problem, and this same lack of formal coherence occurs whether the areas of colour are defined by definite edges, i.e. whether their character as planes is explicit or not. Diffuse zones of colour, with ill-defined edges, move towards the same result, especially if they are conceived as representing a kind of natural light striking the surface of the painting, rather than a kind of light that is struck between the colour relationships themselves, as occurs in the mature Matisse, for example. (With reservations.)

It is clear that when De Stael first began to exhibit in New York in 1950(?) he became aware of the large-scale simplifications of the Abstract Expressionists, and especially Rothko, and his own paintings began to undergo a similar simplification and largeness of scale, but this exposure also confirmed him in his rejection of abstraction, and impelled him further along the path of trying to relate his art to the sun-bathed brilliance of light in the south of France, and to the coup d’oeil of direct sensation from sea and sky. This put him at odds with the Ecole de Paris decorative abstraction, and the Tachism of his peers, Manessier, Hartung etc.

Tachism simply means the expressive potential of the stain, the splash, the pouring of paint, and the surface itself raised to a higher degree of visibility, as pioneered by Klee and Miro.

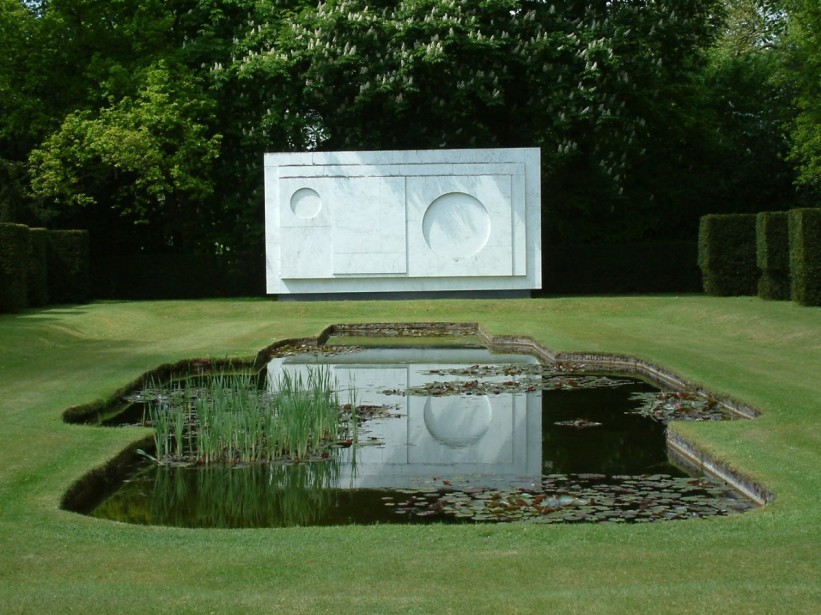

Nicholson is a deeply puzzling and paradoxical artist, at least to me. In many ways his carving conception of space, which he owes in part to Adrian Stokes, is the antithesis of my modelling conception of space in painting. His planar conception is absolutely front on to the picture plane, but in his paintings at least he dislocates, and one has to say subverts his planes’ location relative to one another and to the surface of the panel by subtly overlapping one layer on another, or the illusion of such, and by tilting their edges in an illogical sequence of perspectives allows a counterpoint of lines to contradict, or weave in and out of, the spaces implied by these tilting planes. His line does not cut into depth so much as skate or slide over the fictive spaces afforded. He further complicates things by filling in this jig-saw of interlocking shapes with colour and tone, seemingly, at least to a rational eye, arbitrarily, without any discernible plastic logic.

There is clearly a debt to Braque in this counterpoint of line and plane, but where, in Braque, there seems to lie behind this decorative play an attempt to grasp concrete spatial experience out there in the real world, this grasp on spatial experience is more tenuous in Nicholson, and experienced by the artist at a further remove. Whereas the carving conception of physical contact with the board by way of incisive line takes precedence. Nicholson is in some ways the more abstract, and the more “optical”, but at a price in palpable experience.

The complicated cubist inspired games of 1952 June 4 (table form) Albright Knox Gallery, 1953, Feb. 28th (Vertical Seconds) Tate Gallery , and 1959 August (Argolis) P.C., have a good deal in common with Hofmann’s cubist still lifes of the 1940s, but the push and pull, such as it is, is much more timid and achieved by tonal gradation rather than by colour.

However, August (Argolis) paradoxically seems more coherent as an overall form than De Stael’s Parc Des Prince Grand Footballeurs, – or does it?

But in the spirit of Carl Jung’s philosophy that the integration of the personality requires one to assimilate the suppressed areas of one’s personality, Nicholson continues to exert a certain fascination, at least to me. And without any deliberate attempt to do so, a painting like my Helmsman to Odysseus 2 could be seen as some kind of rapprochement with Nicholson’s art, although it is doubtful if this would have been recognised had I not pointed it out.

Alan Davie is the one artist who found a way to develop out of the biomorphic Picassoidal surrealism of the 1940’s Jackson Pollock, with its prioritising of drawing over colour modelling. You cannot draw nothing. You have to draw something, whether it be biomorphic, anatomical or spatial indicators. But as contour drawing became separated from the delineation of volume in the later work of Klee (another influence on Davie) and in late Matisse, it became the invention of signs for things, calligraphic hieroglyphs, alphabets, even letters, taking primitivism further into the pagan prehistoric origins of iconography.

Across the broad spectrum of modernist pursuits, there are the extremes. On the one hand the impetus towards an unvisualisable and unsayable future, epitomised by Schoenberg’s ” I breathe the air of an unknown planet”, and carried to ludicrous extremes by the maniacal phase of the later Stockhausen. On the other, there is the atavistic attempt to revisit the ancient past, to recreate the sound-world of the pagan pre-Christian origins of ancient religion, even as they survive in the earliest liturgical music, of the Orthodox Russian Church, for instance; a ritualised timeless stasis, as attempted by the post-serial Stravinsky.

The abstract expressionists partook of this latter phenomenon in their “Subjects of the Artists” phase, taking primitivism all the way to an imaginary year zero, the first sign alphabet of visual communication, at the furthest possible remove from the Western European tradition of volumetric representation, accommodated to the flatness of the panel, stemming from Giotto, Masaccio, Fra Fillipo Lippi , Mantegna and Giovanni Bellini.

For a moment Pollock had attenuated line almost to the point of its being free of representation, but this was an extreme moment of style, with which he was deeply troubled, as it cut him off from his earlier inspirations, and from which he returned to allow abstract line to morph into figurative signs in the black paintings of 1952.

But Alan Davie chose instead to follow the implications of the 1942/43 Pollock.

Davie seems to delight in confounding the law-givers of painting and the taste makers. He positively wallows in a profusion of calligraphic signs and modes of representation which defy logic, which should not go together and yet somehow do. No-one is more profligate and libertine with imagery than Davie, perhaps not even late Picasso. Just look at your Persian or Anatolian carpets on your living room floor to see how all embracing are the cultural references and sign worlds that Davie has managed to transform with his mutational writing-drawing. Davie claims to have been influenced by Carl Jung’s Psychology and alchemy. The alchemy fizzes in the paint, and fizzles out when the paint is applied flatly, in his 1970s work and beyond.

Davie’s drawing in Red Parrot Joy No 2 and Insignias of the Gannet People does not cut cursively into depth, or model volumetrically. Instead it maps out broad graffiti-like planes, a kind of simultaneity of shading cum modelling, modelling by overlap, that one can see through, to further planes behind, in echo of Pollock’s all-over dripping, but more muscular/physical. “Brushwork is Spatial”, said Patrick Heron, and even here in calligraphic form, it works to that end.

Heron had made his remark that “there was a continent left to explore, in the direction of colour, and in no other direction” in 1962, following his conversion to abstraction in 1957/58. And he was not alone in being of this persuasion. Following out the implications of Rothko’s simplifications and the dismissal of drawing as an agent of space, a younger group of American painters were following a similar path. Clement Greenberg had essayed a tenuous connection with the staining techniques of Pollock, via the intermediary of Helen Frankenthaler’s Mountains and Sea, leading to Morris Louis’s Veil paintings. But the real progenitor of this out and out colourism was Rothko. So Heron, whatever his protestations to the contrary, was part of a similar chain of influence.

Clement Greenberg remarked that Adolph Gottlieb was pants-presser to the Abstract Expressionists, implying that he tidied up the big painterly gestures of his colleagues in favour of a cleaner, neater image. And he added: if you can’t see Gottlieb, you can’t see the sixties.”

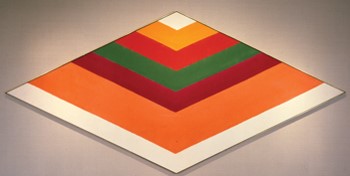

What Kenneth Noland did was to drop one of Gottlieb’s “orbs” down to centre on one of his “splashes”, to create a centralised image, whilst retaining the surrounding areas of unpainted cotton-duck canvas, which has the effect of emphasising the literalness of the painting as object, within which an optical phenomenon is set.

To juxtapose Alan Davie’s Romance for Moon and Stars with Noland’s Bend Sinister is to make the Davie seem very old fashioned, a gulf in the conception of what paintings should give as wide as the Atlantic Ocean itself, and this is precisely what happened to the “middle generation” of painters in England who had come to fruition after the Second World War. Suddenly, and as if from nowhere, there came a radical shift in aesthetic to a cooler, blander and simpler statement of pictorial priority, appearing in the same galleries that had formerly promoted them. Concept was everything, essentially a design concept, and execution carried out using methods that had formerly been the territory of designers and graphic artists, minimising brushwork and individual touch. The St. Ives artists were most affected, to unsettling effect, and many were side-lined in favour of the new aesthetic. Although from another point of view, the Davie may seem a lot richer and more adventurous, this was not the conclusion drawn by the art-world at the time, however.

Noland championed the notion of “making” a painting, rather than painting one, an emphasis on the literal, the canvas, the support, decisions as to where the literal spreading of paint began and ended in the shape of the support; design decisions, in short. This literalism of facture was combined with “opticality”, the suppression of tactility in favour of an optical buzz, pure visual sensation without physical overtones, but differing markedly from Op-art, in that the relationships of colour remained harmonious and did not blur and confuse the eye with flickering effects and hazy mirages.

But as the gamut of design decisions began to be exhausted, Noland reached an impasse in the mid 1970s, and the limitations of his conception began to be exposed as he tried to revivify his earlier successes with gestural “handling” within his signature images, the target, the chevron, and the horizontal banding of narrow masking taped “stripes”.

This kind of heraldic simplicity, the “one shot” instantaneous image, seems to answer to a need in modern psychology, for something final, absolute, “morally decisive and calming”, like a flag, or insignia like that of ribbons on a medal, while at the same time providing a brand image for the artist, a signature style that is his and his alone. And its disavowal of relational complexities, trouble and strife, problems of “resolving”, poses little stress on the capacities of the observer. (There are parallels in contemporary music – Morton Feldman, for example, recently favoured with a six hour long minimalist event at Tate Modern.)

It is worth considering just what is absent from such an approach. We are presented with a stasis, without animation, rhythmic movement, or old-fashioned development, as in musical parlance. However the target format, perhaps Noland’s greatest success, does contain a surprising degree of movement within it as one looks longer. It revolves, like a Catherine wheel, pulses optically,

There is also the thorny question of the claims made for this episode in painting, of the creation of “non-referential” colour, i.e. colour that does not suggest a source in the natural world.

A digression on colour:

To return to “brushwork is spatial” – If the means of application of colour is so impersonal, with all tactility suppressed, with no room for the enlivening effect of the artist’s “touch”, colour becomes so identified with the fabric in which it is soaked (in Post-painterly abstraction), that it becomes just another material surface with no spatial implication, given that “space” in painting is always an illusion.

Working against this literalism is the fact that whatever the “actual” colour, perceived colour is the result of the influence of those colours that lie adjacent to it. In the case of chevrons, the inner colours are sandwiched between neighbours from which they take their colour to the eye, their perceived optical colour. (Just as in music, the sound of any one note or interval is conditioned by its context within the chord in which it is encountered. The same note will sound different when part of a different chord, enharmonically speaking.)

This is as near as one can get to “non-referential” colour – quasi-abstract inter-relational colour. But as oppositions of hue tend to create light between them, there is always the tendency for this “light” to evoke the light falling on the surface of objects in natural sunlight (despite all efforts that may be made to suppress the phenomenon). Paintings in which colour on colour, or colour in colour, is the primary agent of the creation of spatial illusion, however minimally, will simultaneously suggest naturalistic phenomena of colour/light, as we experience it outside of painting, even if it is only fabrics, clothing, flowers, tropical bird plumage, sunsets etc. etc.

Heron engaged in a lengthy and acrimonious argument with Greenberg about the stilted, preconceived design mentality behind the work of the post-painterly faction Greenberg championed, and the focus on symmetry, or near symmetry, which he considered the most boring way to organise a picture, and the lack of discovery through the act of painting which Heron considered essential for true invention in painting. He advocated a ” re-complication” of the picture surface, and the act of painting – “a more considered mode of action, that emphasised the fundamentally static, architectural aspects, at the same time as it involves the fluent and spontaneous” (paraphrasing). “A pre-planned design is always a dead design” (paraphrasing).

To an extent, consensus taste is still albeit unconsciously dominated by the promotional tropes of post-painterly Abstraction, even though the works themselves are denied current agency. There is an inbuilt bias in favour of that smoothly immaculate suppression of the evidence of human agency, the suppression of brushwork that shapes and models surfaces in a spatial way so eloquently described by Patrick Heron in “From Late Matisse” – for fear that it might suggest a figurative space.

For my own part, though I have no theoretical bias against them, when I have encountered Noland’s horizontal bands and shaped canvases in recent years I have been curiously unengaged by them, and when I have studied their surfaces close up, repelled by their fastidious blandness and minuscule textural shifts, masking taped pearlescence perfumed tweaking at the edges. Although intellectually I understand the logic of their empty-centred formats and edge-hugging attempt to activate a pictorial space out of their literal surfaces, I get no excitement at all from their presence.

Similar issues surrounding literalism and spatial illusion through colour are posed by the paintings of Morris Louis and Jules Olitski. Olitski’s remark that he wanted to “hang the weather” does convey the vaporous spatial illusionism he induced by overlaying sprayed colour on colour.

The work of all of these painters is characterised by a glamorous immaculateness and a softness deriving from the inescapable prevalence of the feel of staining into exposed cotton duck canvas, which affected even those paintings in which the canvas was fully covered. We had to learn to like it, so at odds is it with the European sense of tactility of surface of the French/Spanish masters. All during the 60s and 1970s we were in thrall to this glamorous reduction, and the absolute finality of image presented by the post-painterlies, and the formidable critical support they received from Greenberg, Michael Fried and others of that circle. But we found that we simply couldn’t paint that way, even if we wanted to, and we did try. But the gulf in pictorial culture was too great. Our hearts were not fully in it, and little by little the spell was broken, and we began to see these painters for what they really were.

Olitski did try to break out of the immaculateness and the cloudy illusions his spray technique created, with a swing to the opposite pole of brute physicality of surface, exposing in the process the lush hyper-romanticism of colour that was always there underneath; but it was too late. His late work is like Gottlieb all over again, but with exaggeratedly physical surfaces, complete with cracking, as in dried up mudflats in a hot summer.

What can I say?

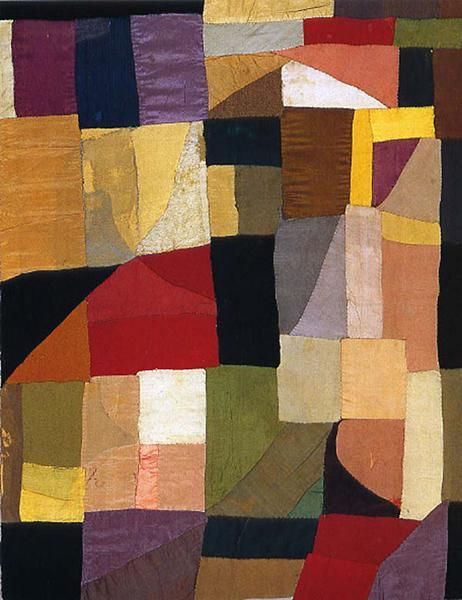

As if to confirm this European antipathy to the stained, immaculately smooth, velvety surface of the cotton duck artists, (which she had flirted with herself during the late 60s,) Gillian Ayres recoiled with a series of heavily orchestrated, tapestry-like, richly adumbrated oil paintings, deeply harmonious in dark and brooding colour, (a rare moment of poise in her far from even work). It took no little nerve and courage to go against prevailing fashion, and to reintroduce a robust layered and scumbled surface in which adjustment and touch played such an important part, qualities that had been all but disallowed by the processes favoured by the post-painterlies.

There has almost always been a conflict in Ayres’s work between painterly fusion of this kind, and decorative pattern. But for a few years from around 1978 to 1982 this conflict was resolved in favour of a kind of all-over unity of sombre rich colour harmony and a fully integrated surface.

However, from the early 80’s onwards, Ayres began to load her canvases with a proliferation of “shapes”, and big gestural drawn arcs and zigzags as if in an attempt to outdo Alan Davie in an assault on taste, and in emulation of her advertised identification with the Venetian masters. Her painting process was, and had been, cumulative, accretional, layered, but the sombre harmony of paintings like Ultima Thule, Bellona and Sabrina became sacrificed to a welter of jostling lozenges, ovoids, spangled with droplets and dolly mixtures, bounded by harsh contours in a compartmentalised space, sewn or tied together by aggressive thrusting of the arm. The delicate balance between surface unity and decorative pattern became once more problematical in her art.

Here “abundance” is taken literally, and to an extreme, akin to the best work of Davie in the early 60s, but without the quality of molten fusion which he attained at his best.

There is a continuity here, running all the way from the homologous ever present surface of late Monet to Jackson Pollock’s all over fractured continuum, to Davie’s “intuitive romantic” plastic physicality, to Ayres’ rich Christmas pudding surfaces, a simultaneity of surface unity that ultimately is owed to the impressionists’ vision.

From here on the story becomes more personal, intertwined with my own developing convictions of taste, rivalries and influences. The 1970s were wilderness years, as my friends and I struggled to discover a way round the influence of the Americans, both the Abstract Expressionists and the post-painterlies. After my first visit to New York in 1972, I tried out some of the ways of painting I had seen first hand there at the studios of Noland, Olitski and Poons, (with Poons especially – he is just two years older than me – I had a phase of mutual influencing when he visited my studio in March 1971). We were continually being pulled back to these influences with every visit Greenberg made to see our work, right through to 1977-78. But in 1980-81 I finally sloughed off the last vestiges of influence from the post-painterly approach in favour of the direct hands on adjustment of colour and surface with a more physical touch, having much in common with Ayres’s work as I see it now in retrospect, though at the time I was scarcely aware of what she was doing, neither of us having much opportunity to show our work in London.

After a period when Heron’s disputational wrangling with the Greenbergian aesthetic seemed to have a deleterious effect on his own painting, he returned to form in 1982-85 with a new impetus of originality with the Garden Paintings, shown in a retrospective grouping at the Barbican Gallery in 1985. He followed this with a sequel of equally original garden paintings in which drawing played an increasingly important part, at the Camden Art Centre in 1994.

To be continued as PART 3: “Contemporary Trends.”

Alan Gouk, November 28th 2016.

This essay appears by kind permission of Hampstead School of Art, where it is to be given as a lecture.

You can’t say everything at once, otherwise Part 2 would have been twice as long as it is. When I deliver it as a talk at Hampstead School of Art I intend to ignore the text and just respond to the images, which tell their own story.

Delaunay’s Premier Disc is perhaps the best “target” ever. It has no colour theory, bears no relation to the spectral wheel. It is pure invention in colour of a very high order, and the light that is generated through the juxtapositions and adjustments of colour and tone is as unnaturalistic as the best Klees.

It makes Frank Stella look devoid of any artistic purpose, just pointless decoration.

LikeLike

Smashing !

LikeLike

maybe Alan is going to write all the comments?

anyway here is one from me and its not about the text.

the best thing here for me is the image of Alan’s painting “Wichita Lineman”.2017

If you have a few minutes click on it and get the full monty and try not to think of where it has been squashed into.

It has been painted only last year,

I don’t know but its probably acrylic paint.

It does not matter to me nor how big it is.

In his “A word from the artist” from the HSOA catalogue of his “Mandalay” series last year he says he hopes for a “cavalier boldness of attack”.

This painting has that no doubt. It has a stand up for itself attitude which has no need for add on explanation. To say the paint flows is an understatement . The colour and the fluidity merge together and describe that ineffable quality that paint can have when it is both relaxed and controlled.

It is something to look and learn from if you are an Abstract painter today.

I found it a it disconcerting that Alan puts his painting in direct comparison to Hofmann’s “In the Wake of the Hurricane” 1960…….For what its worth I think “Wichita ..” is better…The greens and oranges are more heavy handed in “…..Hurricane” and the whole thing is more laboured…..I don’t need to see that comparison …maybe Alan’s painting is only a reality because Hofmann painted his first but in isolation I am not bothered about Hofmann .I love the Gouk for what I have said already and for its subtle strength.

The Hofmann relies on a strong format. Whether I call it format or configuration I think “Wichita….” falls down a little because all of its great qualities do “hang ” on a bit to a hidden structure which I keep discovering…and maybe that is not quite Abstract?

But brilliant….

Bring on 2017 and 2018 and on and on and on and on………

LikeLike

In haste: great comment, Anne. A friend here in New York and I were kind of talking about the same thing. We were talking about a distinction between “historical determinism” and “personal determinism.” We give Alan “points” for looking outside of himself for “justification” of his work—but we kind of question that too. We have doubts about the “squashing in” business. (We also give Alan “points” for his erudition, great writing, etc., etc.)

I still just don’t understand what you mean when you, Anne, talk about being “abstract.” I can understand Abstract Art as an historical thing that began at the beginning of the 20th century. I can understand there being an abstract “dimension” to all drawing/painting/sculpture: form, space, etc.

But I just don’t understand what you mean when you talk about hanging on to a hidden structure not being “quite Abstract.” It doesn’t really bother me. There’s plenty I don’t understand. But I’ve been reading this essay by Joseph McElroy: http://www.electronicbookreview.com/thread/technocapitalism/censorious. I think MAYBE it’s “quite Abstract.” There’s kind of no “format/configuration” “hidden” inside/under it.

And, of course, it’s fun/natural to think about abstraction and censorship, “historical determinism” and censorship, etc., etc. What’s “in”—what’s “out”. . .

No mention of de Kooning—or the great Studio Schooler Esteban Vicente—in Alan’s text—and Alan has questions about de Stael’s “light”/value structure. MAYBE that’s what’s “missing” in Wichita Lineman—what makes you feel Alan’s “hanging onto” a kind of artificial/intellectual/not completely integrated/“hidden” structure.

Got to go. But: thanks, Anne—thanks, Alan. . .

LikeLike

I too find “Wichita Lineman” to be a very good painting. May I query your stricture on structure? I suggest that if you dispense with structure you will tend to homogeneity. I would prefer to see you slip up and reveal yourself; only then would we know the person behind the brush and obtain insight into a unique object that may turn out to be painting. I dare even suggest a landscape manifests itself a la Hitchens in “Wichita”, though Alan’s painting is far better than Ivon’s. I for one don’t really care if it can be categorised as “fully abstract”. I might add that musical progress is (as analogy) not always as straight as an arrow; follow Prokofiev after Webern.

LikeLike

My comment above is in reply to Anne.

LikeLike

There is nothing at all wrong with structure, Pete, and the more the better, provided it is discovered and embedded in the content of the work and does not belong elsewhere, i.e. in a landscape or piece of graphic design (it’s ironic that a really good landscape painting does not adhere to a “landscape” format). Structure in an abstract painting is not derived from anything external.

It’s instructive to see just how much of the history of abstract painting is contrived as semi-figurative, or has a crude and clunking format (all those bloody suns!), and when it doesn’t have that it becomes literal – what a poor painter Noland is.

What a great and unexpected comment from Anne, and I’m fascinated to see how Alan responds. As I tried – perhaps rather too subtly – to hint at in his HSOA catalogue introduction, the way that Alan now rather violently but fluidly warps and bends space is adding up to something rather original. I don’t like all his new paintings, but something is afoot in some of his work that is indeed more real and exciting than pretty much any of the other illustrations in this text. Cheeky to say so, but I can’t help but think it is actually Alan’s intellectual link to history that holds him back a little. Maybe getting all this off his chest will be a good thing.

LikeLike

to Pete…

…”only then would we know the person behind the brush and obtain insight into a unique object that may turn out to be a painting”

It is that word “unique” that makes me feel you are answering your own question…follow up with …”it may turn out to be a painting”..well what a wonderful dream !!! and it sounds like you are telling us something you already know about Abstract.To me if it is “unique” it will not carry any associates.

to Jock..

You have made me do what I said what I did not want to do. ..to comment in a comparative way in respect of the Hofmann and the Gouk.

The ‘little’ problem I refer to is present in both of these works.

It is where the paint IS on the canvas. Not the colour of the paint and not what the paint does. Seeing that in them both I sense something external.

The Gouk for me remains terrific.

LikeLike

Reading Alan Gouk’s essays is a pleasure and a real learning experience for me. It helps me to really see the paintings as I haven’t seen them before. If I can make time, I’d like to add some comments on his view of Kenneth Noland’s pictures, and I wish he’d devote more space to Morris Louis.

LikeLike

Noland a poor painter — I don’t think so. The fact that I said I have been unengaged by them in recent years — The fault is no doubt mine. I wouldn’t have reproduced so many if I thought he was not a major painter. I tried to show only paintings I actively like, although one or two have crept in for historic reasons. There are over a hundred, so whilst flattered at the attention, I am puzzled as to why only my picture has been singled out. Even I can see that it is not the most impressive on display.

LikeLike

Well, it’s a matter of opinion, but I don’t see what is so very good about paintings that are identical for every inch along their ten foot length. The last Nolands I looked at were at Pace London a while ago, and I though they were anonymous and unfelt. I did go and see a big Noland show in Tate Liverpool quite a few years back, but that too was disapponting, mostly due to the repetition, but also by the total reliance on somewhat uninspiring and flat colour to do everything. Compared to the Delaunay “Disque”, the Noland targets look perfunctory. But for me even the dazzling Delauney colour, though beautiful and intuitive, is not enough to make a wholly satisfying painting.

As for “Wichita Lineman”, well, I haven’t seen it, and I look forward to doing so, but from reproduction I wouldn’t necessarily have singled it out myself (though I think Anne’s comment is excellent). I would, though, go so far as to say that “Mandalaysian Orchid” from your HSOA show would give anything here a good run for it’s money. (But I did have the advantage over most viewers at that exhibition of seeing it in Isabel’s back garden, where you could get more than two feet away from it, and in daylight too.)

I also think the three big Heron “Garden” paintings look good in this company, whilst what I had always considered his best work – late fifties, early sixties – looks a little predictable now. Hofmann and Pollock are the really big artists in this batch, for me, and the two painters that somehow have to be seriously reckoned with.

LikeLike

I have been imbibing Alan’s analyses of painting ever since he first started them; indeed, I have a whole collection in my library. The ineffable quality of his writing continues to persuade and instruct. He once told me that he had ” the gift of the gab”. Well, what gift, what gab !

Inevitably, on reading his ‘musee imaginaire’, I was led to wonder what the equivalent sculpture ‘musee’ would be like by comparison and whether it too could be taken as a route to the present. One thought struck me, of the comparative amount of dedication to abstraction (even if loaded with figurative and clunking references) in XXth C. painting history.as chosen for this ‘musee’. The ease with which [painters have moved into abstraction compared to the sculptors.

The answer to a question as to why this should be the case, I suggest, lies in the subject matter germaine to painting; not only the figure, but landscape. skyscape, still life, architecture, environment, etc., etc. in short the world; a far greater range than sculpture’s dogged but fundamental representation of the figure, which dominated even the most valiant abstract attempts with few exceptions.

If Impressionism is the fount of modern painting and all that has followed, where is sculpture’s Impressionism ? Certainly not Rosso, far too insignificant. We only have Rodin, and he can hardly be called an Impressionist (despite all the guff about his modelled ‘surfaces), leading to a continuous stream of development as in painting.

Perhaps, right now, sculpture has a better chance of acquiring a truly abstract means of expression in its soul by dint of its previous lack, but will its nature allow ?

LikeLike

Tim

…this resonates a lot for me..fantastic..

Structure is part of Abstract sculpture because it is a reality together with the actuality of the material.

Paint comes out of a tin. It involves brush work and a myriad of decisions to get an Abstract actuality.There can be an uneasy coalition between applying the paint to a surface and making form which sometimes results in a false structure.

That is the fundamental difference for me.

I envy the clarity that sculptors are gaining for themselves today.

LikeLike

What the pioneers of Abstraction feared most was that in leaving representation behind, what would be left would be meaningless decoration, or “merely” formal abstraction ( whatever that means). They did want to express the “mysterious centres of thought”, and though their attempts at a theoretical justification border on the incomprehensible or nonsensical ( to a Logical Positivist), it does not follow that the resultant paintings are meaningless. That would be to think that only what can be coherently articulated in words has meaning.

All visual art involves “Vorstellung” — the representation of an imaginative idea projected into pictorial space (or sculptural space). The subtext of Part 2, which only revealed itself in the course of the writing, and the more I looked at the images, is that hardly any of the painters who have made up this rich panoply would have achieved what they did if their vision had been blighted by a strict view of Abstraction, or if they had tried to define it doctrinally. The exception is probably the austere Mondrian. (I’ll have more to say about him in Part 3). But one can see that in New York City 1941 and the other pictures of 1943-44 Mondrian is moving to a much more exploratory approach to colour, a counterpoint of interlocking grids, a veritable pin-ball machine for the eye as it ricochets from one overlap to another. As in so called absolute music, all manner of kinaesthetic sensations are evoked. Call it Abstraction if you must.

LikeLike

But now that we know for sure that “abstract” is not about “purity” (how I hate that correlation!), and now that we know that, of itself, in the fullness of its visibility, “abstract” can carry independent and free meaning, can we not, now, at last, fearlessly leave all representation behind, along with everything that comes with it. I just don’t think that the alternative to semi-abstraction or semi-figuration lies in austerity, and whilst I think you are right that to date most abstract painting and sculpture has relied upon it, I think we can now do without “Vorstellung”.

Discovery, not representation is the key to “abstract”, as you start to hint at even with late Mondrian, and in sculpture at least, my experience is that “abstract” is rapidly becoming its own discipline, with its own strictures to weigh against the freedoms won, and quite different from what has gone before under the catch-all of “abstraction”. (Which is just one of the reasons why I think new abstract sculpture really is “new”.)

LikeLike

Regarding Alan Gouk’s remarks on Kenneth Noland:

Of course, what I have to say is hopelessly stuck in the past. Not being an artist myself, I don’t have much choice in the matter.

“What Kenneth Noland did was to drop one of Gottlieb’s “orbs” down to centre on one of his “splashes”, to create a centralised image, whilst retaining the surrounding areas of unpainted cotton-duck canvas, which has the effect of emphasising the literalness of the painting as object, within which an optical phenomenon is set.”

1. Dropping one of Gottlieb’s orbs down to the center alters not just the location of the orb but also its function and its significance. (The fact that this alteration is not relative but absolute suggests something about the kind of “influence” one artist has on another in modernism.) One of its functions in Noland’s pictures is that of “centering”, which means it is not so much an image within the space of the picture as a way of establishing a connection between the depicted discs and the support itself – the size and shape of the canvas of which it is the center. Is this accurately described as “emphasizing” the literalness of the painting as object?

“Noland championed the notion of “making” a painting, rather than painting one, an emphasis on the literal, the canvas, the support, decisions as to where the literal spreading of paint began and ended in the shape of the support; design decisions, in short.”

2. Noland “makes” a painting as opposed to “painting it.” What does this mean?

In a subsequent comment, Alan says this: “What the pioneers of Abstraction feared most was that in leaving representation behind, what would be left would be meaningless decoration, or “merely” formal abstraction ( whatever that means).”

All paintings are, after all, objects existing in time and space, and as such may be viewed as meaningless decorations or formal designs. With the abandonment of representation (and therefore of illusion), this brute fact became a threat to the continued viability of the art of painting generally and Noland’s desire to make paintings in particular. If so, then Noland’s decision to center his pictures by means of the disc may be described as finding a way of claiming (without denying) the support’s literal qualities (size and shape) for art. The same may be said of his decision to anchor or hand his colored wedges from the upper corners of the picture. “Claiming” the support’s literal qualities for art (when those qualities could no longer be simply ignored in favor of illusion) was a way of “suspending” (temporarily, so to speak, for as long as the experience endures) the painting’s literalness as an object in the only way it could be suspended – by making the painting “abstract”.

3. You say that Noland championed the “making” – as opposed to the painting of – a painting, and that this meant that his decisions were ultimately “design decisions”. The assumption seems to be that that in order to escape being seen as mere design, or as decoration, the painter’s decisions must be expressed or manifested as movements traditionally associated with painting pictures – for example, movements of the hand and wrist. (I hope I’m not misinterpreting.)

Noland may have felt that movements of the hand and wrist were no longer capable (as far as he was concerned) of making things that mattered as paintings. I think that by the late 1940s, Jackson Pollack felt something similar; his overall paintings of that time also avoid the traditional actions of painting, and they don’t manifest movements of the hand and wrist in anything like a traditional way. But nobody who appreciates his work would say that Pollack’s paintings amounted design or decoration.

To say that a painting by Noland is “made” (as opposed to “painted”) is to say that (1) the concept of style has no clear application to what he was doing, and (2) the way Noland’s pictures were made refers to the technical procedures he used. To refer to “technical procedures” (in lieu of style or manner for example) implies that there is no longer any established (e.g., by convention or tradition) connection between those procedures and the results they produce. Nothing is permitted to come between the idea and its realization.

To say that nothing comes between the idea and its realization may is a way of saying that the artist’s responsibility for making the picture is more important than the manner in which it is made; it has become absolute. What has changed since the early 1960s? Is there now something else than an artist may rely on apart from his or her own conviction, that is, will to make art?

LikeLike

Thank you Carl for returning the discussion to the substance of the article just in time before another hymn to the unparalleled “newness” of Robin’s sculpture, with which all these discussions seem to end. (By the way, I don’t think abstract painting has anything at all to learn from abstract sculpture, or vice versa. I thought we all agreed on that by now.)

On the issue of “making a painting” — these were Noland’s own words for what he was doing — I can only go on my own experience of observing his way of working on a few days at his Bowery studio in 1972. I do think that they were design decisions, but not only design decisions. The end result is a pictorial experience, a spatial experience, but one of a minimal plasticity. I do not think that movements of the wrist have anything to do with it. It is a question of how the colour is spread, how substantial the sensation of space through the physicality of the paint layer, or layers etc.

On my visit. Noland was using industrial type buffing machines to allow the paint to impregnate the surface so totally as to be almost invisible as a separate layer from the duck itself. This was to enable the narrow bands which would go at the edges to also sit IN the surface rather than to have thickness that would cause them to be seen as over the surface. Noland sat atop a pair of step ladders instructing his assistants in the location of the masking tapes that would locate the horizontal bands that would rake across the broad central field. The illustrated Another Line (above) is similar to the paintings he was making then, but Sun Bouquet 1971 is even closer. Needless to say the colour was very close toned and high keyed. And so on ……

In Principle, Appearance, Style, 1974, I wrote ….. “ After the first simple intuition to make paintings which involved horizontal extension plus elision, through more delicate hue variation than he had been accustomed to using, Noland rapidly ran the gamut of variation in band width, hue variation and grouping, picture size, height and width, until arriving at the single centred horizontal broad-band paintings with breaking narrow bands at top and bottom, of 1970. These latter horizontals tend to read as a whole of course, but also as a kind of gentle rising up and across surface and gliding down surface by vertical drifting of the eye across surface; in doing so, slight but crucial illusions of sinking and floating, in depth as well as up and down , occur, at times no more than a ripple, at times with considerable sharpness. I do not see that there is anything to prevent these illusions from becoming more emphatic…….A single colour break would not sufficiently blur the relative location of picture plane and central band, nor induce the delicate spatial shifts, planar tensions and liftings which tease the surface into subtle illusion. Noland ‘s surfaces may be “all colour” but they are not “just colour”. They achieve a number of things spatially also………. etc.

So I think you can see that I have always considered Noland’s pictures to be pictorial, and not just design. But a lot of the stuff about claiming the shape of the support for Art I no longer buy.

When Heron says “brushwork is spatial” he is not talking about wristwork, but that the way paint is applied influences its spatial impact, that touch is an important way in which plastic feeling is transmitted, and evincing a disappointment with these bland cotton duck surfaces that I have come to share. It’s a European thing.

LikeLike

In 1968 I had been doing my own aggressively shaped canvases which projected from 2D to 3D, influenced not by Noland but by Richard Smith … of whom I wrote — “ The final step in the development of what are now amongst the best paintings being made, was the increasing use of three dimensional frontal depth perspective, which allowed the colour to take its place in the surface, which could be shaped and bent in perspective and geometry. This permitted the whole painting as object to lend itself to the propensity in perception to see the total configuration of an object as an immaterial image of form, while precisely locating colour in an unfluctuating relationship within the overall structure of the form. In other words the tendency for for colour areas to fluctuate ambivalently in spatial location in “flat” painting, is counteracted by the further cues of shape. Integrity of the picture plane is not at issue, for the picture plane is itself shaped by three dimensional geometry in controlled perspective. Here space and colour form s single unified entity which does not refer beyond itself”. So you see I do know a bit about the shape of the support etc.

That is where I stood in 1968. I have moved on since then, but seeing one of Richard Smith’s big multiple shaped canvases at Tate Britain recently, I found I still liked it, and liked it more than Noland’s Another Line, on display in the same room, along with a vast, vapid Olitski spray painting, more than 20 feet long, not nearly as good as the ones I’ve illustrated above. In fact not a good painting at all.

LikeLike

The artist sat atop a step-ladder whilst minions run about with industrial buffing machines? Did you manage to keep a straight face for the duration? Was it scripted by Galton and Simpson?

You know, just because it forms a part of your personal history does not make it any the less INSANE.

I’m rather amused to see you still like Richard Smith – again part of your own story – but what about Hoyland, who made some very good paintings in the sixties and seventies? Nothing. And dare I mention Stella’s “Protractor series”?

LikeLike

It seems to me that objecting to work of art on the basis of how it was made is, for better or worse, an exercise in futility.

LikeLike

That’s not what I did. I made fun of the anecdote, but I objected to the paintings because they are boring, as even Alan seems to admit about one or two, without deigning to explain why some are good and some not. Whereas I suppose you, Carl, like them all on principle, because of some moral imperative?

LikeLike

Not really, Robin, I like them because the experience of seeing them (and others produced during that period) in person years ago was strong and lasting enough to affect the way I see paintings to this day. And that was before I had read much art criticism. although I can’t deny that reading the best criticism of the 1960s was also formative for me. The principles involved still seem valid because I have been unable to find others to displace them. (I don’t deny that this may reflect limitations on my part rather than eternal truths. I also don’t deny that quite a few of Noland’s pictures are boring and repetitious; it’s hard to think of any artist whose work does not at some point lose inspiration at some point.)

LikeLike

A good example of the difference between the European aesthetic of “brushwork is spatial” and the wearying effect of staining into cotton duck 🦆 is De Stael’s Le Concert. It too is a very large painting, some 10 feet high by over 20 feet long, painted on primed canvas in oil paint (and all these things do make a difference plastically and spatially) which gives the paint film a certain “lift” and the colour a liveliness, a bite and a fluidity (difficult to describe precisely).

The myth is that De Stael had been to a concert of Webern’s music in Paris, rushed back to the south of France and in a frenzy of inspiration, painted Le Concert and then jumped to his death from his studio window. However there is a photograph of him standing in front of the massive stretcher, which he must have either ordered up before going to Paris, or have had to wait to be made and delivered.

The truth seems to be that he was under intense pressure to produce for a number of dealers (since he was in high demand), and had developed a drug problem to give him the energy to work long hours.

De Stael is a genuine and highly intelligent painter with lots of perceptive things to say about his own and others work.

The role of the colour in Frank Stella’s protractor Paintings , as compared with the Delaunay Premier Disque , is arbitrary, brash and decorative in the pejorative, ie simply an infilling within a design, not a fault that could be attributed to Noland.

On Noland’s Via Blues, also about 20 feet long , — Noland asked David Annesley to send him examples of fabrics for deckchair covers, presumably not available in the US. so that he could see unusual combinations of colour, but he did not simply arbitrarily copy them. I have not seen Via Blues, but it looks to be one of his most challenging paintings. Don’t mention Bridget Riley!

LikeLike

PS. I often look at my paintings in progress from the top of a pair of step ladders too. Nothing wrong with that in itself.

LikeLike

But presumably you dismount to actually paint them – yourself?

Sorry to go off topic again, but yesterday I happened to open a book on Durer at the illustration of an etching, “Hercules”. At every point, in every corner of this work, is evidence of Durer’s engagement of brain, eye and hand. Wherever you look is inventive delight. The “whole” is not an idea about the whole thing, but a “continuity of experience” of the whole thing. There is no reason that I can see why abstract art should not strive to this end.

And as for judging a painting by how it is made, Carl, I would refer you to the endless faddish machinations in thrall to materials and technique, gel application and painting machines etc., etc,. of the Mashomack Triangle Workshops run by some of your favourite artists and critics. All gone by the board now.

LikeLike

…and still no mention of Hoyland…

LikeLike

LikeLike

“All gone by the board now.” Yes, and just look at the crap that has displaced them.

LikeLike

That clunking bipartite Composition is precisely why I wasn’t able to include Hoyland in the survey. I’m afraid that in Hoyland’s case the desire to emulate Hofmann’s strongly saturated colour had a negative effect on his painting overall, though this one is better than most. He gets stuck with a rigid design early on , repeated in painting after painting, and resorts to working it up. There is no give and take, no flexibility, no flow of imagination, and in your words, no “discovery”. Form in painting should be discovered anew with each painting, not clunkingly imposed on it from the start, or near start.

LikeLike

“He gets stuck with a rigid design early on , repeated in painting after painting, and resorts to working it up. There is no give and take, no flexibility, no flow of imagination, and in your words, no “discovery”. Form in painting should be discovered anew with each painting, not clunkingly I posed on it from the start, or near start.”

Those could indeed be my words, but how can you say that about Hoyland and still support Noland? Your partiality is bemusing.

I don’t think Hoyland is a really great painter, but better than Noland and Olitski, on the whole, especially in the sixties and seventies. But obviously he’s not part of your story. He certainly looked the best artist of the three at Pace Gallery “Caro, Hoyland, Noland” show, no question. But we’d better leave this topic alone, I think.

LikeLike

My critique of Hoyland by comparing him unfavourably with Hofmann also dates from P.A.S. in 1974 (studio International), and probably did as much to damage my career as did British Sculpture at the Whitechapel 1and 2 (Artscribe). But what Hoyland demonstrates is that willpower alone cannot turn a clumsy artist into a great colourist, or even a good one.

LikeLike

Imposed, obviously.

LikeLike

Loads here, but for now…

in partial answer to this question:

“He might equally well have asked how the anti-art subversive pranks of the Dadaists and Surrealists were transformed to become fertile material for the imaginations of true painters like Arshile Gorky.”

John Golding says this:

“the Americans – because of their own cultural and geographical situation – found themselves profiting from the intellectually liberating properties of Surrealism in a more down to earth and visceral fashion than European artists of their own generation. It was because of this that, while capitalising on its heritage, the Americans were able to distance themselves from the more esoteric aspects of Surrealism, from its game-playing, from its somewhat incestuous desire to shock not simply the intellectual community at large, but rather themselves and each other. There is a very real sense in which the Surrealists represented the culmination of a European romantic sensibility which spans over a century and a half, while the Americans represent a reappraisal of those sensibilities and their most fundamental tenets”

LikeLike

Thanks Sam. An interesting quote indeed.

LikeLike

I can’t remember Golding mentioning Matisse very much in his account, but I wonder whether you could see the Abstract Expressionists as involved with an abstract art which remained “wedded to the full lustre of the sensory world”

LikeLike

Big subject, but no, not really. See my articles in Abstractcritical on Reappraising Pollock and the earlier Letter From New York 2012.

LikeLike

Except for Hofmann through his fauvism roots. But I don’t really accept “abstract expressionism” as a meaningful category in any case. See also my review of the A E’s at the R .A on abcrit.

LikeLike

Please wait for Part 3, where I will have to say more about Hoyland, although having said that I tried to show only paintings I actively like, there will not be many Hoylands on display. However in terms of accuracy it has to be acknowledged that he spotted the importance of Hofmann’s fiexible vision of the possibilities of Abstraction early on, even though his derivation is all too evident.

LikeLiked by 1 person