Heavy, with the Weight of History

On the 27th March 2018, I contributed a comment to a long and smouldering debate on Abcrit, following the publication of Alan Gouk’s tremendous Key Paintings of the 20th Century: Part 2. The comment read as follows:

I’m in no way suggesting that we are yet to see an abstract painting. I’m saying that there is no appetite for that as an un-compromised artistic pursuit in our current prevailing culture. Rather paradoxically, we have a situation where there are more “abstract painters” than ever before, but just as so many of these painters are capable of pulling off some rather good paintings, many are just as capable of drawing a smiley face into one of them the very next day. This is because there doesn’t seem to be any sense that a critically engaged audience is watching. Casualism is to a great extent born out of a perception that no one actually cares. This is very different to the climate that gave oxygen to the painters in your survey, Alan [Gouk], and from what I can gather, quite different to the critically engaged times you yourself came up in, able as you were to exchange ideas and have your work seen by the likes of Greenberg and Fried. The tide may already have been turning then, but it is at its lowest ebb now. The fact that we have to resort to google to try and find new or interesting artists is a massive indictment on how far things have fallen, and how isolated we all are.

Actually, I made this comment on the 28th of March, because Australia is about eight or nine hours ahead of England, despite the general lament that we are ten to fifteen years behind in regards to everything else. Australia is no stranger to isolation. The illusive Southern Continent, that last piece of the imperial puzzle, a vast and sporadically populated landmass surrounded by endless sea. This is a place people were sent to so they would disappear. As Robert Hughes wrote in the Fatal Shore:

… transportation got rid of the dissenter without making a hero of him on the scaffold. He slipped off the map into a distant limbo, where his voice fell dead at his feet. There was nothing for his ideas to engage, if he were an intellectual; no machines to break or ricks to burn, if a labourer. He could preach sedition to the thieves and cockatoos, or to the wind. Nobody would care.

Eerily familiar. Barbarism aside, the most significant difference today, as I see it, is the repeated assurance that our voices matter and will be heard. The world has shrunk, so they say, and we’re all supposedly much more connected, and yet it feels as if we’re all just shouting over the top of each other, silencing ourselves in the process, creating a new breed of repression. In colonial Australia, repression was the local currency. We have always felt like this, and it contributes to the manifestation of The Cultural Cringe, that peculiar, archaic but ever present inferiority complex, the reverence for the ‘homeland’ suffered by post-colonial nations but particularly Australia. It’s a complex that has impeded our cultural development, devaluing everything we make here in favour of almost anything from Europe and America, because of our insecure and guilt ridden view of ourselves, born out of the knowledge that this isn’t really our country.

For an international reader-ship not so familiar with this concept, the phrase was coined by Arthur Angell Phillips in his seminal essay, The Cultural Cringe (1950). Its origins however, can be traced back as far as the late nineteenth century, to the articulation of the concept by the poet Henry Lawson. I am extremely wary of the potential dangers presented by any attempt to weigh in to this heavily charged and divisive discourse. It may well be too complex a topic to take on for the purposes of this essay, but to some extent it is unavoidable. Let it be said that The Cringe has evolved and in some cases, been outgrown, but nevertheless, it continues to shadow the Australian consciousness across every conceivable cultural endeavour.

So, it is only fair that I examine my own personal relationship to Brancaster Chronicles, the UK based forum for exhibiting and discussing abstract art, of which I am a participating member. Was my sense of the importance of these forums and the work which has developed out of them, which was of course strong enough to motivate me to travel to England to see it, brought about by an undeniable recognition of the content and quality of the work and discussion in its own right, or by my own insecurities about the worth of Australian culture itself? I would like to think it was the former and I have reason to believe that it is, but it would be immature to dismiss the possibility that I wasn’t persuaded by some inherited sense of European authority, and that I may perhaps be less pre-disposed to recognise the value of home-grown efforts. Many Australians think and feel that way and I don’t think I am any different. Artist residencies, study exchanges, overseas shows, these are all rites of passage for Australian artists, and although these are opportunities that artists the world over make use of too, in Australia they seem to be coveted very highly indeed, affording the artist an air of respectability they may not have previously enjoyed. These are all valuable experiences that I wouldn’t discourage anyone from pursuing. This is simply something for all Australians to be aware of, but particularly artists, who so often end up leaving Australia in search of better opportunities overseas, but perhaps at the cost of postponing the inevitable confrontation with the cultural dilemma back home.

I say dilemma, because the question of how best to address that cultural problem is where the ground becomes more treacherous still. In Australia, to simply be seen to defy The Cringe is often accepted by the public as more than adequate, but it can result in the reinforcement of cultural clichés and stereo-types, through the self-conscious perpetuation of typically Australian iconography. This predicament is examined in Terry Smith’s 1974 essay, The Provincialism Problem. He argues that the questionable power structures of metropolitan art centres, in this case New York in the 1970s, spreads subservience and dependence. Smith writes that Australian art before the 1950s, “like its political history… is typified by variations on the theme of dependence.” As a result, the provincial artist “is never himself the agent of significant change. Larger forces control the shape of his development as an artist.” He observes that the provincial artist’s world is characterised by a certain bind,

…replete with tensions between two antithetical terms: a defiant urge to localism (a claim for the possibility and validity of “making good, original art right here”) and a reluctant recognition that the generative innovations in art, and the criteria for standards of “quality,” “originality,” “interest,” “forcefulness,” etc., are determined externally. Far from encouraging innocent art of naive purity, untainted by “too much history and too much thinking,” provincialism, in fact, produces highly self-conscious art “obsessed with the problem of what its identity ought to be.

Australian abstract artists, by rejecting the requirement to perpetuate iconography, may also find themselves trapped in this bind, because whilst their work may have more appeal to an international audience, it can struggle to leave any impression at home, which is ultimately where it will need to be nurtured. Its dismissal as being self-involved can result in feelings of guilt.

Guilt is a common Australian trait, but abstract artists suffer from it all over the world, because of abstract art’s apparent lack of a social conscience. In Australia, that social conscience is inextricably linked to an increased awareness amongst white Australians of the harms done by them to the Indigenous people and their culture, and a moral sense of duty to right the wrongs and maybe even see that culture reinstated. This produces an intriguing manifestation of The Cringe, and an awareness of it produces a damned if you do, damned if you don’t attitude to creativity and its national significance. A. A. Phillips addresses this in his 1950 essay, specifically in reference to the Jindyworobak literary movement, which was comprised of white, predominantly male authors, who sought to integrate the uniquely Australian environment and Aboriginal history into their writing, whilst also rejecting the infiltration of any European imagery. Phillips observed that:

The Australian writer cannot cease to be English even if he wants to. The nightingale does not sing under Australian skies; but he still sings in the literate Australian mind. It may thus become the symbol which runs naturally to the tip of the writer’s pen; but he dare not use it because it has no organic relation with the Australian life he is interpreting…

A Jindyworobak writer uses the image ‘galah-breasted dawn’. The picture is both fresh and accurate, and has a sense of immediacy because it comes direct from the writer’s environment; and yet somehow it doesn’t quite come off. The trouble is that we—unhappy Cringers–are too aware of the processes in its creation. We can feel the writer thinking: ‘No, I mustn’t use one of the images which English language tradition is insinuating into my mind; I must have something Australian: ah, yes—’ What the phrase has gained in immediacy, it has lost in spontaneity. You have some measure of the complexity of the problem of a colonial culture when you reflect that the last sentence I have written is not so nonsensical as it sounds.

In Australia, the search for identity that has often been the stomping ground of our cultural elite, often produces work that nobly but at times egotistically advocates the role of the artist as mythmaker. Our most celebrated painters tend to be the ones who personify the very male dominated sphere of ‘folklore’, pitting man against nature, bushranger against policeman, underdog against establishment. What Phillips cites as a problem for Australian Literature, can be extended to Australian painting, which has its own history of self-categorisation. On a visit to the Drill Hall Gallery in Canberra last year, I got to see Sidney Nolan’s River Bend from 1964-65. It is a frieze comprised of nine paintings that follow the slight curvature of the room, depicting a bush scene that bulges forward or recedes dramatically in accordance with the bending river. Painted in enamel, it has a surface quality that doesn’t feel overly indebted to the European painting tradition. The representation of the water is ghostly and flat, yet sets off such a bizarre contrast with the apparent meatiness of the trees, contradicted by the fact that the trees themselves are comprised of very little paint at all. I found this work extremely evocative and an accurate reflection of my own perceptions of space in the Australian bush, particularly on the Murray river. In some ways, it makes an absolute mockery of the abomination that is David Hockney’s A Bigger Grand Canyon (1999), which resides close by at the neighbouring National Gallery. Unlike the Hockney, which is embarrassingly flat, Nolan’s painting becomes almost virtual in the way it wraps around your field of vision, somewhat capitalising on our own optical limitations as the receding peripheries are thrown into further degrees of uncertainty. The problem though, is that Nolan feels compelled to include an ancillary and superfluous element to this already distinctive and resonant bush scene by peppering it with his trademark Ned Kelly stick figures fighting policemen in the wilderness. How else would we know it was a Nolan? How else would it help to fill the “gaping hole” in our national mythology?

Terry Smith takes note of the problem faced by Nolan and artists in a similar position to him. He writes:

Nolan’s greatness is of a different order from [Jackson] Pollock’s. Nolan is admired as a great Australian artist, while Pollock is taken to be a great artist – his Americanness accepted as a secondary aspect of his achievement qua artist. In such circumstances, the most to which the provincial artist can aspire is to be considered second-rate.

For Smith, the provincialism is what simultaneously makes and breaks Nolan. What he has to do to attain significance at home, is what limits the reach and impact of his work away from these shores. It should be mentioned that some overseas audiences through unfamiliarity may enjoy these parochialisms, but moments of approval from audiences at home and those abroad rarely seem to align. To repeat A. A. Philips, “we unhappy cringers are too aware of the processes in its creation.”

This insecurity about cultural signifiers filters through into much of our ‘abstract’ painting as well, which feels compelled to reference the Australian landscape in order to deliver meaning. As Smith also observes, “a range of exploration conventional to the categories of international art, with a touch of local colour, seems fundamental to the way Australian art develops.” For myself, I find the referencing of things like landscape and other figurative devices in work that otherwise lays some claim to being abstract, to be quite alienating at times, which is the opposite effect that would have been intended. It has something to do with the fact that I feel like some sort of barrier has been erected between myself and the artist, as they resort to well established and accepted conventions in order to justify and mediate an activity that is otherwise their most direct means of personal communication. When these conventions are so readily adopted, it is as if the artist is not taking full responsibility for their work, and riding on the coat tails of somebody else’s achievements. As Alan Gouk pointed out recently, those somebodies often end up being Joan Mitchell and Philip Guston, American painters not without their own flaws, and it is on their account that scores of contemporary abstract artists readily and without question adopt a “hell for leather” approach to paint handling that through its complacency tends to have very familiar results.

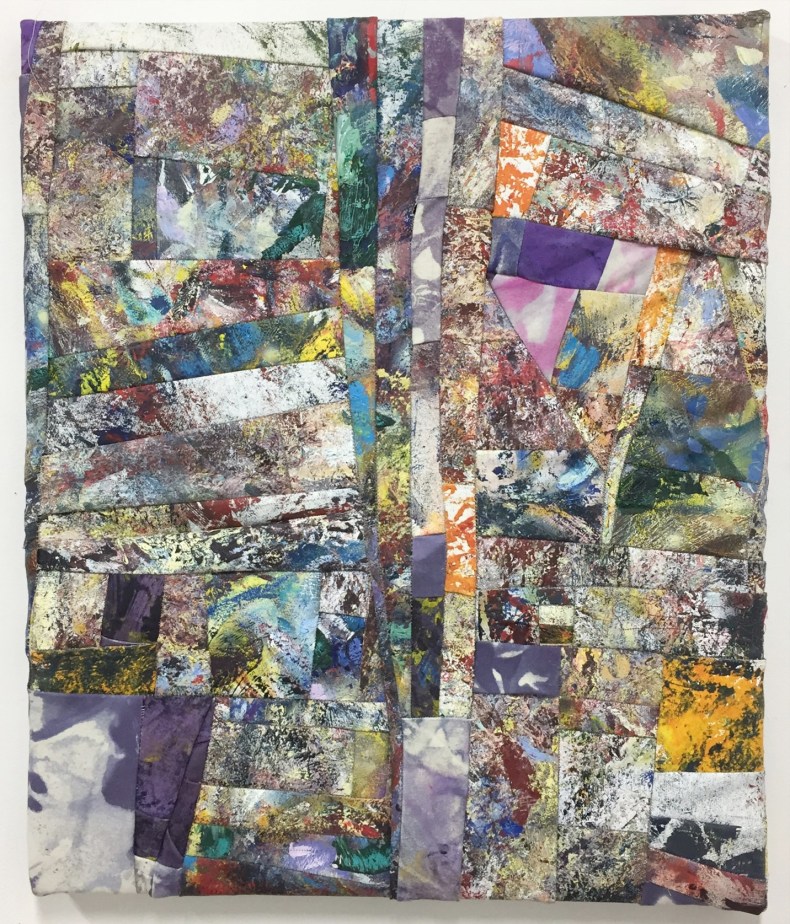

Here is one example:

I came across none of this in Brancaster Chronicles when I first started delving into them. That is hardly surprising given that the forum exists in England, a country with a more developed awareness of abstract art, but the paintings did not even bear any traces of the St. Ives style, that of greyish land and seascapes, often abstracted by wildly expressive brushwork, somewhat reminiscent of wind in the paintings of Peter Lanyon, or the calm, still airiness of Ben Nicholson. Whilst I understand the importance of these works and the significance they hold for many an Abcrit reader and contributor, these are not paintings that I can feel any strong connection to. This is not a blanket criticism. There are bound to be exceptions. But I think the reservations are there because the work is inextricably linked to the cultural sensibilities of those familiar with the environment that gave birth to them. Their ‘Englishness’ works for and against them. So, in that respect, why should we expect an international audience to fully appreciate or comprehend the ‘Australianness’ of our painting?

Brancaster painting, sculpture and collage for that matter, does not look English, to me anyway. In fact, it does not appear indebted to any concept of cultural identity. Brancaster painting and sculpture is rich with visual stimuli. It is in many cases uncompromising in its search for something that is not over-reliant on figurative conventions. It is expressive and spontaneous without being wild and romantic. It is considered and purposeful without being tentative or pre-conceived. Ultimately, I find it very rewarding to look at, because it privileges the freedom of the viewer to seamlessly move anywhere at any time, in any direction, rather than the freedom of the artist to do whatever s/he wants, which is an overrated freedom often culminating in tropes, a fall-back alternative to the tyranny of ‘infinite choice’. Perhaps just as importantly, Brancaster fosters a culture of cooperation through peer review, and the consistent development of the work is testament to this. I would nominate this collaborative approach to abstract art as being perhaps one of the most necessary antidotes to overcoming the cultural alienation outlined at the beginning of this essay. For a fuller account of my experience of Brancaster work, my review of the group exhibition in Greenwich last year can be read here: https://abcrit.org/2017/04/17/61-harry-hay-writes-on-brancaster-chronicles-at-the-heritage-gallery-greenwich/

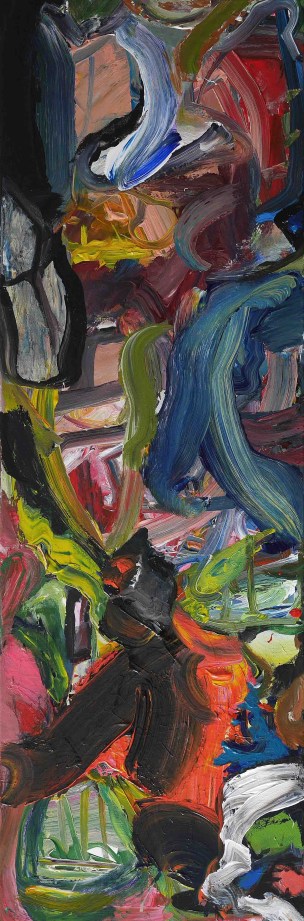

More recently, I had this to say about the work of John Pollard and Anne Smart, who are both Brancaster painters, in a comment responding to Robin Greenwood’s essay about Content and its Discontents:

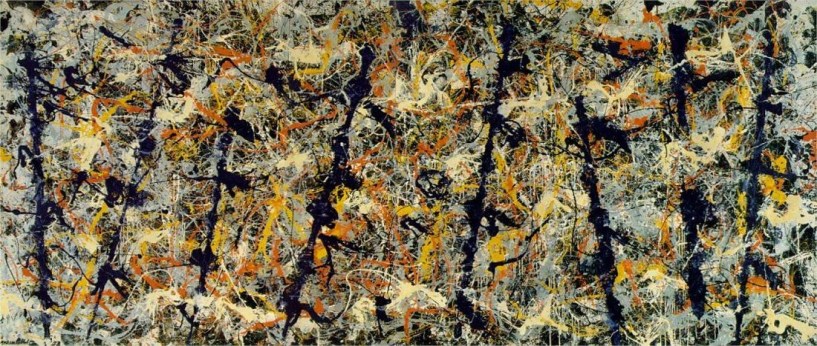

Does the density of content, when precisely adjusted to lead into any of the other moments in any possible direction, create a kind of mental imbalance for the viewer? By imbalance, I mean that if we want to, we can lock ourselves into any part of the painting for a considerable period of time, and at the expense, for that time, of the rest of the content, but only for that time, because of the freedom we enjoy of being able to spend just as long somewhere else in the painting, and neglect the part that so utterly engaged us prior. We end up with an ever-shifting visual hierarchy, which can only be achieved by making every square inch equally as important as each other. The shifting of focus can throw the peripheral information into a kind of depth, but it is not necessarily destined to stay there… I feel that it is quite different to how I look at quite a lot of abstract art, which often asks us to take in the whole work at once, to be engulfed, and not get lost in pockets. This may still be the more radical approach, and I still feel challenged by (Jackson) Pollock for instance, and the ramifications of what he did.”

It was no mere accident that led me to cite the work of Jackson Pollock. His Blue Poles (1952) is the pride and joy of the National Gallery of Australia in Canberra. It is probably treasured as highly, if not more so, than Nolan’s Ned Kelly series, for reasons hardly surprising given the earlier quotation from Terry Smith. I’ve probably seen Blue Poles three or four times, but the only decent crack I’ve made with it came last November. It is very hard to find writing about Blue Poles and the Whitlam Government’s controversial approval to acquire it that displays some originality of thought, and does not descend into polarising narratives about the price tag, whether it be “the waste of money” it was criticised as being at the time, or the “valuable investment” it is hailed as today, which in turn generates more bitter cries from the far Right that it should be sold to pay off the nation’s debt.

I did however manage to locate one article that offers a different take on the whole affair, oddly enough by attempting to gauge just how good a painting it actually is. The essay is by Giles Auty, British born émigré and previously the arts writer for The Australian and The Spectator. The article was first published in 2006 by Quadrant, a notoriously conservative journal that espouses some pretty toxic opinions at times. But nevertheless, Auty’s essay is an attempt to put Blue Poles into some sort of perspective, historically, financially and artistically.

Auty’s article can be read here: http://www.thejackdaw.co.uk/?p=1605

Auty is critical of some of the guff put forward at the time of the Blue Poles acquisition, notably by Max Hutchinson, who brokered the deal and made the claim that “Blue Poles, along with Picasso’s Guernica and Monet’s waterlilies, is one of the five or six great works of art painted since the Renaissance”. Auty scoffs at this obviously ridiculous statement, proceeding to cite Hutchinson’s colleague Sandra McGrath’s attempt to water down the aggrandisement by adding, “it is certainly one of the five or six great paintings of the twentieth century”. Auty’s view is that Blue Poles is not even a good Pollock, and he uses Pollock’s own words, that it was a “failure”, and the unfavourable commentary it received from Clement Greenberg as proof of this. I don’t think that such citations close the case once and for all, but judging from my own experience of Pollock’s work, I would say that it is probably less radical in what it achieves than some of his other paintings that I have seen, and struggled with.

The total immersion pioneered by Pollock in paintings like Autumn Rhythm and One: Number 51 (both 1950), require a kind of awesome homogenising of the surface. I do not mean this in a pejorative sense. The homogeneity or equality across the whole work denies the temptation to look for focal points or integral passages. You take it all at once or not at all, though that is a simplification, because I have often found I’ve had to work to appreciate these paintings. Yet Blue Poles goes some way towards introducing a series of focal points, seven in total. I wouldn’t go so far as to say that they become objects in a figurative space, but they are not so fully subsumed into the rest of the paint work that they utterly cease to be either. The procession creates a left to right reading of the work that sits at odds with the all-over immersion of previous works. I don’t want to suggest that it therefore fails as a painting, but that it might have been antithetical to what Pollock was trying to achieve.

Unfortunately, Auty avoids this kind of examination of the painting and relies upon the accounts of others to draw his conclusions about the artistic worth of it. Even when he claims that his opinion of Blue Poles has been formed by the comprehensive exhibition he saw of Pollock’s work at the Tate, he hastens to include that he “imagine(s) that a number of other professional commentators who are similarly familiar with Pollock’s work would agree with me.” The essay makes some fine points, but ultimately it is Auty’s conservatism that is the essay’s undoing, but not because of its lengthy dissemination of the economics of the purchase, nor because of Auty’s position on “novelty” or pseudo-progressive rhetoric. Rather, it lies in Auty’s inability to sympathise with the Australian condition, somewhat pardonable given he didn’t arrive here until 1995. It doesn’t seem to matter to Auty that whether or not the painting is good or bad is of absolutely no consequence to Australians, who as he points out, own very little else in the way of exemplary Western art to hold Blue Poles up against. And we never will! For us to be repeatedly told that the painting is a masterpiece without providing us with much else to compare it to is indeed alienating. But so too is telling us that the painting is overrated without adequately explaining why, and then lamenting the “tragedy” that is our national collection. This only contributes to our insecurities and reinforces the view that we are “second rate”. Whether it be because of our insecurities or in spite of them, Blue Poles holds an extremely important place in the Australian cultural psyche.

Gough Whitlam and James Mollison would have understood the national significance of the acquisition. They would have hoped that it marked the beginning of a Modern and independent Australia breaking free from the clutches of Old England. It didn’t really matter that the painting was already twenty-one years old, and that the artist had been dead for seventeen. It also would be unfair to say that the purchase symbolises the shifting of Australia’s allegiances or dependencies, and the transferring of our sovereignty over from Britain to America, not that this is suggested at all by Auty. I only add this in anticipation of the potential room to criticise the Blue Poles purchase as another manifestation of Cringe. It would be unfair, because of all the other local initiatives laid out by the Whitlam government that gave opportunities to artists at home, such as the establishment of the Australia Council, and the fact that Aboriginal artists started to be recognised during Whitlam’s tenure. As art critic Jeremy Eccles writes, for the Aboriginal Art Directory in 2014, “What does matter is Gough’s reputation – which should be recognised for taking assimilation off the table and allowing Indigenous culture to flower. As one facilitator who was around at the time said to me: ‘Imagine the art world before Gough – it consisted of the Bush Church Aid Association in Bathurst Street (not Sydney’s most plush thoroughfare) hiding marvellous barks away in a back room if there was any sign of genitalia! He brought it out into the open and the funding he gave the Aboriginal Arts Board allowed all that we have today.’”

Auty’s recommended solution to sweeping away the mystique and hysteria around Blue Poles is hinged upon something that could never happen here, which is for Australia’s museums to be filled with European masterpieces, and not only that, but that Australian children should be forced to learn about them as well. Tell that to the remote communities of the Northern Territory, or the rapidly growing migrant populations in the sprawling suburbs of Melbourne and Sydney! I have come to realise that even if our museums were in a position to acquire such works, they should not be trying to compete with their European and American counterparts. They attempt to anyhow, and it is to the detriment of the arts in this country. For an in-depth analysis of the shortcomings of the National Gallery of Victoria’s international agenda, read Giles Fielke’s review of the Melbourne Triennial, here at https://memoreview.net/blog/triennial-at-ngv-international-by-giles-fielke .

Imagining for one moment that Auty’s suggestion is sound (which it probably is to a European), that a journey through the past would enrich and inform our perspective of Pollock’s Blue Poles, a painting we own but do not fully appreciate, would it not be equally possible that an analysis of the present, and what has come since Blue Poles, could also inform and enlighten us as to some of its remarkable achievements and deficiencies. I know that I myself have come to appreciate artists like Pollock more by paying closer attention to my own work and that of my peers, and realising how very different it is from something like Blue Poles, despite it being able to attract the same tag of being ‘abstract’. Assuming that my perceptions of Anne Smart and John Pollard’s paintings have any accuracy, a comparison between my account of their work and Pollock’s reveals that an enormous shift in thinking about abstract art has taken place. As exciting as these new possibilities are, they also make me all the more impressed at the tense equality of Pollock’s surfaces given how much he was doing to them. Such an outcome seems completely unattainable for my own work, and this is largely to do with the pressures of the historical moment Pollock found himself in. Yet he seized that moment and turned it into something real, a moment that can never again be repeated, and makes all attempts to do so look fraudulent. For Australian abstract painters to look back at this moment, and compare it to their own, could prove quite beneficial, and force a complete reversal of what we are always taught, that Blue Poles and other paintings like it signify the end of the line for painting, the last port of call before the inevitable disembodiment into performance and conceptual art. What if it was only the beginning?

This April, Chamber Presents, an artist run gallery situated in Brunswick, an inner-city fringe suburb of Melbourne, will host Heavy. Curated by artist Simon Gardam, with a little help from myself, it brings together a collection of abstract paintings that share similarities in visual density and the development of idiosyncratic content, despite being made by artists who come from a diversity of backgrounds. This diversity is not part of the show’s emphasis, nor did it form any prerequisite for who should be invited to exhibit. It is merely something that can be noted. Jiaxin Nong for instance, is a Chinese born painter living in Melbourne. Tom Dunn is an Australian painter living in Los Angeles. John Pollard, whose work I discussed above, is English. This information might be trivial, but given the nature of this essay, it seems appropriate to draw some attention to this, symptomatic as it may be of Australia’s outward looking condition. In a way, it brings me back to my comment about the global abstract painting culture and the sheer volume of painters making interesting work today, but the ever-present danger of slipping into complacency because of the lack of a pressurised environment. Perhaps one way of remedying this lies in identifying a range of artists with similar concerns and just getting them in the same room together. I honestly don’t know if Heavy has any ambition greater than this, other than the unique concerns that drive the individual painters involved.

It seems strangely fortuitous that Heavy should open the very same week as the NGV’s The Field Revisited, which re-stages the 1968 exhibition of Australian Minimalism that launched the museum’s new and current premises at St. Kilda Road. The re-staging however, will not take place at the original St. Kilda Road venue, but at the Ian Potter centre, because the former venue is now the NGV: International (Oh Là Là!). The history of the NGV is in many ways a symbol that traces Australia’s own cultural growth and subsequent regression, from British Colonial outpost, to forward looking and aspiring sovereign nation, to “that next large rectangular state beyond El Paso… (to be) treated accordingly” (President Lyndon B. Johnson according to Marshall Green, US Ambassador to Australia, 1973-5).

What the NGV did in 1968 was extremely ambitious and predictably controversial. Arguably, The Field was an even more radical gesture than the purchase of Blue Poles, which was already twenty years old, and brought to Australia’s attention at a time (1973) when the country was waking up to itself. The 1960s on the other hand, were still suffering from the post-Menzies stupor, and it would not be hard to imagine how much hysteria could be caused by a painting of simply ‘nothing at all’ appearing in a national museum, and for the venue’s inaugural exhibition, no less. To add insult to injury, the paintings and sculptures were made by Australians, forty of them, with no less than half of them aged at thirty years or younger! These artists were engaging in a current and internationally recognised movement in art, and probably punching well above their weight too. Was it the Cringe, or Smith’s Provincialism Problem that motivated these artists to fix their focus on the world stage rather than to look inward for their content? Possibly. Yet it doesn’t really seem to matter, because the exhibition, and the purchase of Blue Poles five years later, was a huge challenge to the conservative establishment, signalling a severing of the Imperial umbilical cord.

Fast forward fifty years, and now The Field is the establishment, and it is to them we come crawling back. Where is the 2018 equivalent of The Field? Where is the NGV’s exhibition of new, locally made, internationally engaged abstract art? I’m not suggesting that The Field shouldn’t be celebrated, but it is downright hypocritical of the NGV to boast of its importance whilst failing to recognise the example set by their former self, and the potential rewards of investing in the here and now. They have become a shining model of neoliberalism, a mirror image of the Australian Labor Party, seeking approval by asserting their progressive credentials and working-class roots, whilst funnelling public money into the hands of big business.

If The Field Revisited whets your appetite for abstract art that challenged conservative tastes of the time, but leaves you wondering whether anything of similar ambition is happening in Melbourne today, I would suggest heading out onto Swanston street and catching the number 1 or the number 6 tram up to East Brunswick. In a small laneway, in what looks like it could be somebody’s garage, you might just find something that goes some way to subverting the familiar narratives about abstract art in this city. I make no grand claims for the artists in Heavy, other than that they are young and committed to developing the personal content of their work, and are largely uninhibited by rules and reservations about when something is “too worked” or contains “too much”. Whether or not a non-referential content driven approach to abstract painting contributes anything in the way of outgrowing The Cringe is largely unanswerable, if not unhelpful to have to consider whilst trying to develop content that is both personal and universal. But when it comes to abstract art, the international art community is in this together, and history has shown that when Australians apply themselves at the coal face, they are just as capable as anyone. The cultural uncertainty that exists on an international level today, may mean that Australia now finds itself no more handicapped than any other country, and possibly even at an advantage, due to years of experience.

I would say that what I have learnt from examining Blue Poles and the discourse around it, is that cultural maturity in Australia will not be achieved by becoming more insular. In painting, The Cringe is something to be challenged, but not necessarily by mining the resources of our inherited imagery and hoping we get used to hearing the sound of our own nasal voices, but by paying close attention to the unique content and possibilities in painting today as it emerges, and if some of that work is happening in England, so be it. Let us not go the way of the Jindyworobak movement and miss out on exciting developments on the grounds of cultural incompatibility. None of this in itself will rid us of The Cringe, which I think is here to stay for a long time to come. Its origins go back too far, to the very theft of the land itself, the subsequent genocides, and the sad fact that reconciliation has not yet been achieved. With that in mind, it would be quite easy to dismiss abstract art as something of a self-indulgence. But time and time again, its pursuit in this country is dogged with political controversy, whether it be in the examples I’ve addressed above, or the ones I provide below, which I was unable to work into the thread of this piece. It would appear that abstract art has played an undeniable role in Australia’s maturation.

Heavy opens on April 26th at Chamber Presents, 19 Church street East Brunswick, Melbourne, Australia. It features the work of Mary Barton, Tom Dunn, Simon Gardam, Harry Hay, Merryn Lloyd, Jiaxin Nong and John Pollard. The show runs until May 6th. https://www.chamberpresents.org/heavy

Postscript:

I could have made mention of the furious controversy surrounding Vault (aka Yellow Peril) by Ron Robertson-Swann. Public condemnation of the sculpture saw it relocated from its original position in Melbourne’s city square in 1980, prompting massive counter rallies.

Mention could also have been made to the Betty Churcher review of the Parliament House Art collection in 2004, after protestations from conservative ministers Tony Abbott and Ross Cameron, that the collection was full of “Avant-Garde crap!” The report recommended that the requirement to only purchase work by living artists be lifted, finding that “some members ‘object to all abstract art – seeing it as elite and not representative of broader Australia.’” (Betty Churcher quoted by John McDonald).

It seems to me, that being an abstract artist in Australia is controversial almost by definition.

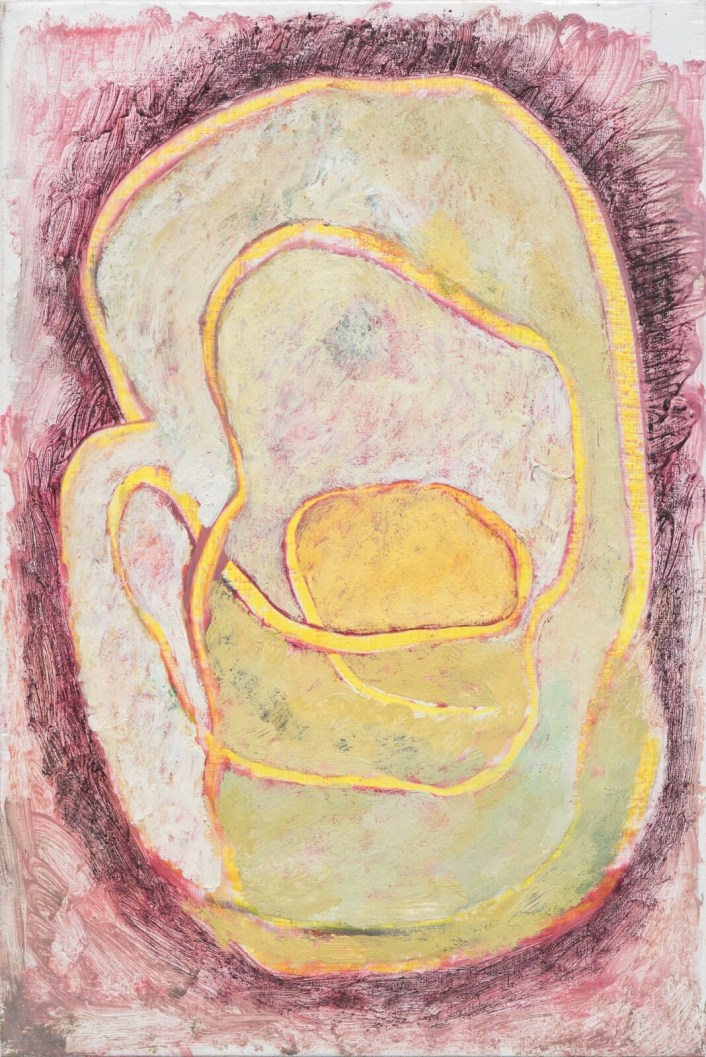

Some work by the artists in “Heavy”:

Simon Gardam, “The Quickest Way to Get to the Future is to Wait”, 2018, oil and synthetic dye on canvas, 60 x 50 cm.

Bibliography:

Auty, G 2006, “Blue Poles”, Modernism and the Novelty Trap, published by Quadrant, re-published by The Jackdaw, 2015, http://www.thejackdaw.co.uk/?p=1605

Eccles, J 2014, Whitlam Maligned by Fairfax, published by the Aboriginal Art Directory, https://news.aboriginalartdirectory.com/2014/10/whitlam-maligned-by-fairfax.php

Green, M quoted by Pilger, J 1989, A Secret Country, “The Struggle for Independence”, p. 139, published by Vintage Random House.

Hughes, R 1986, The Fatal Shore, “Who Were the Convicts?”, pp. 175-176, published by Vintage Random House.

McDonald, J 2004, Culture in the Age of Howard, published for the Australian Financial Review Magazine, re-purposed at http://johnmcdonald.net.au/2004/culture-in-the-age-of-howard/

Phillips, A. A. 1950, The Cultural Cringe, published by Meanjin Quarterly, https://meanjin.com.au/blog/the-cultural-cringe-by-a-a-phillips/

Smith, T 1974, The Provincialism Problem, first published by Artforum, accessed via search.proquest.com

What a brilliant article. Not for the first time Harry, you have restored my faith in the capacity of younger artists and yourself in particular to understand “the pressures of the historical moment”, and to respond intelligently, just at the point when I had decided that there was no more ,for me , to be gained by contributing to the rancorous and endlessly repetetive debate on abcrit, with its embarrassing litany of stupid accusations of “apologist for semi-Abstraction”, “yours is a lost cause” and the like. Try re- reading the comments following Geoff Hands’ article on Howard Hodgkin for instance. (The sequence on Nick Moore on Gillian Ayres I’ve mentioned before, equally repetitive in outcome). I had already decided to withdraw entirely, and to withdraw Part 3 of my trilogy, since it would only lead to yet another salvo of prejudice against everything in modern painting that displeases Robin Greenwood. I may have to think again on the former, but certainly not on the latter, Part 3 I mean.

The only reservation I have about your article is the tendency to slip into the same misuse of the word “content” that peppers the discourse on abcrit following Robin’s constant talk of “putting in” content. Eg. “Idiosyncratic content” and “try to develop content that is both personal and universal”. This can only lead to the heavy laden density and potential clogging up of space that many of your examples exhibit. I offer once again the best definition of “content” that I know of — namely Robert Motherwell’s — “ The content of painting is our response to the painting’s qualitative character, as made apprehendable by its form. This content is the feeling ‘body and mind’”. And a potential imbalance between the impulses of body and mind is just what is at issue in some of your examples. You can no more “put in” content than you can be profound on purpose. All you can do,is follow your own nose and let out what you’ve got to give.

It may seem that this on Content is merely a semantic quibble, but words have consequences, and so does their misuse.

Despite Robin’s recent disparaging of the very idea of “quality”, it is this imponderable that makes the difference between a well meaning but laboured exercise, and a painting in which the juices are flowing. You may disparage the word, but it is harder to talk away the consequences.

It will not be lost on regular readers that despite howls of derision on comments from the last article on Content etc. , your examples show that there is a commonality of concern in painting that is not confined to the participants in Brancaster, who have no special purchase on the issues involved. Well intentioned focus, yes, but no privileged insight.

Ps. I’d suggest that the Pollard painting illustrated might be better as a horizontal. It is difficult to see it at present, stretched out as it is across two pages of the screen. After all,it is smaller than some of the others above it. And it does seem to fuse all the influences I mentioned before. I forgot to add early Jackson Pollock, no bad thing in itself.

LikeLike

The best claim one could make about Brancaster being not quite part of the provincial scenario, with all its dilemmas, so clearly outlined by Harry, is its connection by direct line of succession to the debates about the “onward of sculpture”, and by association of painting, stemming from Anthony Caro’s Influence at St Martins School of Art, where almost all of the participants were students, and the Forums that carried that debate forward beyond his direct influence, and through the joint exhibitions of painting and sculpture at Stockwellll Depot.

It was that thread that connected all of us to the bigger world, don’t forget, outside of the English parochialism and the small world of the English Art school system, until officialdom finally brought it to its knees , you’ll recall.

Let’s not go back there, to a conception of “onward” that denies the radical innovations of 20th Century modern painting and sculpture as I have tried to describe it in Key Paintings. I did not write these for my own benefit, but for yours, if you did but know it. I didn’t need reminding. You did.

LikeLike

The reason why Joan Mitchell, Philip Guston, and all the other abstract impressionists can’t hope to rival the marvellously varied brush drawing in late Monet’s paintings of the Alles des Rosiers, the Weeping Willow tree, the View of the House from the Rose Garden, the Path through the Irises 1918-25 (Mrs Walter Annenberg Coll.), and the others in the Musee Marmottan, of which there was a whole room of fine examples in the R A’s Garden show a year or two ago, is because they lack object matter, things to paint, Japanese Bridge, cupolas, avenues of trees, rows of poplars etc.

It is these formal and figurative elements that give scope for the range of brush drawing in which Monet is unrivalled in all of painting, and to emulate this will inevitably lead one to a return to figuration. I have always wanted to paint like this, but it is foolish for abstract painters to try to do so without the physical presence of “things”. (It would be quite wrong to think of this as “content”. It is just material , motifs , structural potential). Many have tried — early Morris Louis (Trellis), late Cy Twombly (I well remember his vast dribbles in homage to Monet in Encounters at the National Gallery in the early 1990’s ?), Milton Resnick, the later Larry Poons — all have failed, because the derivation is too obvious, and the comparison with the original too embarrassing, as well as being semi- figurative.

How to escape from this — there is a lesson from the drawing in Jackson Pollock’s 1950 period, and why Blue Poles is not a successful picture. Those seven blue/black poles sort of stand in for the presence of “things” in the world, and as such they sit uneasily within, on top of, or proud of the genuinely abstract elements of Pollock’s true drawing style (which is not quite as monolithically all of a piece as Harry describes).

This effort (not a sleeping effort— it is too deliberate, too wilful) — to create a dance rhythm across the expanse of such a large painting fails because it is too clumsy an attempt at integration, and utterly unrhythmic in fact. The poles are like the tribal insignia carried aloft in ceremonial dances of American Indians, or so they came to be regarded after the fact by commentators, I imagine.

In his paintings of 1950, Pollock avoids abstract Impressionism by suppressing or minimising colour. Add colour to the mix and you’re well on the way to an impressionist all over style, such as Pollock attempted earlier in Eyes in the Heat and Croaking Movement, 1946 and the somewhat later Scent , and White Light 1954. These are far from great colour paintings.

Go ahead, make my day and prove me wrong.

LikeLike

Yes really well written piece Harry.

Alan Gouk has also made an important point about ‘heavy laden density and clogging up of space’ when referring to putting more content into an abstract painting. There is always a balance to be aware of and Mark Skilton’s comment about complexity not becoming just complicated is also very relevant.

Learning from Monet’s masterful techniques and somehow using them would need a new structure and organisation within an abstract painting to take the place of objects. I don’t necessarily think it is an impossibility, but sometimes, like Alan has implied, there can be a watered down semi abstractness which leaves you wanting more, (thinking of some,not all, by any means, of Joan Mitchell’s paintings).

LikeLike

Yes indeed, balance in everything. But if you don’t take the risk of complication, you will never make for yourself the opportunity to arrive at a synthesis of complexity, which is the state of grace achieved, in all manner of ways, by great art.

“All you can do, is follow your own nose and let out what you’ve got to give.” Uninspiring and slipshod words; advice followed by a million second-rate abstract artists. You can and should do a lot more than that.

The fact that as abstract artists we no longer have the motif or anything else that figurative artists – painters especially – had to take us outside of ourselves and get us beyond the banalities of easily-arrived-at compositional devices only means that we have to work all the harder at developing abstract content that takes us to new places, to things that are outside of our ken. I don’t suggest “putting in” content at all, since there is nothing – unless you use such devices– to put it into. But then, if that is how you think, then no wonder the idea of abstract content gets mashed up into a nonsense.

There seems to be a considerable amount of angst associated with being an artist in Australia. These days, that seems strange. I wouldn’t worry about it. Brancaster has no nationalistic affiliations. And it is a pity that “Blue Poles” gets so much attention. On the couple of occasions I’ve seen it, it’s been an unpleasant experience; a clogged-up over-complication. So Pollock took the risk, with some success, but in the end his way out of it was a rather sad return to figuration. We have to go further. We have to follow Hofmann’s advice to look outside of ourselves, beyond our own “natures”. As abstract artists, that can only mean one thing.

LikeLike

Yes, but you see, that angst is in all likelihood one of the reasons that I have any involvement with Brancaster and Abcrit at all. What I’m writing about is an inferiority complex. To tell Australians “not to worry about it” is all well and good, but it’s a bit like telling someone with serious anxiety to just pull themselves together. It looks a lot easier from the outside.

Australia is characterised by “beaut” weather and sunny dispositions to match. But the reality is we are an anxious people often lacking in self-confidence, yet feel obliged to keep this to ourselves. We sweep everything under the carpet.

As I write this, I am starting to think that rather than suppress this anxiety, we should cultivate it. It may well be the thing that propels us further. Art, if it has any worth at all, has to pursue truth. The anxiety is real, but perhaps it is only debilitating when it is denied.

The point I was trying to make about “Blue Poles”, which I don’t know if it has registered, is that its own artistic quality is unknown to us, and therefore quite irrelevant to Australian artists. This is unfortunate because it holds such a dominating presence in our cultural awareness. It was always going to, there was no way around this. The kind of formal analyses offered by Alan, Robin and myself in the essay, is something I rarely if ever hear from other Australians, and we own it! Therefore, rather than have us (Australians) play catch up, I suggested that we invest our time in abstract art made since, and maybe, if we are bold enough, let our art of today teach us about the art of yesteryear, rather than constantly feel indebted to a history that is not ours.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I can assure you that the kind of formal (or otherwise) analyses of which you speak are rarely heard here either; or anywhere, for that matter. But I like the idea in your last sentence, which chimes with Brancaster and why you (and all of us) participate. The thing is that I no longer feel that I ought to be wholly indebted to any particular history written by others either, not even Alan’s. We are all in the contradictory position of being part of a global connectivity, being able to access anything anywhere, at least as images or comment, whilst simultaneously being thrown back very much on our own personal resources because all the threads of history seem broken. There is no longer any “mainstream” to feel any FOMO about. History and chronology are important, but to me “the pressures of the historical moment” are something of a mirage. My connection with art and its meaningfulness is where I choose it to be – which was the point of my essay on content.

Two things seem very important: to get to see as much art as possible first hand, in order to make up your own mind about it; and to realise that the issues of abstract art are not best dealt with alone, but need a reasonably objective airing in the company of others, even whilst recognising that one must take personal responsibility for everything you do and not blame it on context, cultural or historical. And whilst both those things are possibly made more difficult by your location, you yourself have shown that they are these days surmountable.

LikeLike

Anxiety will be present in many different ways: anxiety with failure and disappointment, criticism by others, or maybe a free floating existential type of anxiety that seems to be about ‘no-thing’ at all. I go with the idea that anxiety can be about uncertainty and relates to our freedom and hence responsibility to make decisions and act in our uncertain world/condition. Perhaps pursuing abstract art tends to reflect such a view of uncertainty, whilst figurative art always gives one a hold, a connection to a wider world, outside of the act of painting.

Of course abstract artists can also have such a constant fixed and comforting certainty, whether it be politics, techniques, familiar motifs, etc. And I’m not saying this will result in bad art just as I am not saying that a freer, and perhaps more anxious, way of being an artist will result in good paintings.

I don’t like the phrasing of ‘cultivating’ anxiety, as it reminds me of gauloise smoking, cafe-dwelling, black polo tops, and an attempt to objectify one’s being, resulting ironically in bad faith. But I do think anxiety is something to be understood and not suppressed as you suggest Harry. The desire to suppress can lead to a certainty, simplicity, something easily recognisable, that fits in to our already worked out known world.

I found the work at the abstract expressionism exhibiton at the RA last year generally disappointing, but putting that to one side I can see how exciting that work was back in its day. How might looking forward 60 years looking back at what we are painting now be judged? And can that in any way give us some clues of the attitude to take to making abstract art now?

Anxiety may be a part of this attitude.

Can we be pulled towards a future rather than pushed by the past? What ideas can help with being pulled by an uncertain future?

LikeLike

Well said Harry. Also exhibiting abstract (non- objective) art this festival of the Field weekend in Melbourne is a community of over 100 artists, ‘Abstraction 2018’ at Langford 120, Stephen McLaughlan, Five Walls, JAMM and Deakin Univ. The discourse is alive and well!

LikeLike

Thank you Lisa. I guess the difference with “Heavy” is that its connection to the festival of the Field was a complete coincidence, but one I’m happy to draw attention to.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Just to clarify something, what I should have said was that I have never heard an Australian artist or critic give a compelling account of Blue Poles where they confidently make a judgement as to its “quality”, one way or the other. Rather than lamenting a lack of formal analysis, I was rather observing a lack of confidence in being able to draw conclusions about something we have more access to than anyone.

Robin, you and Alan, but also Giles Auty and Clement Greenberg can say with confidence that Blue Poles is a failure, because of the access you’ve had to a trove of greater examples of Western art. I am Australian, and I have to make an “each-way bet”, and say that “I don’t want to suggest that it therefore fails as a painting, but that it might have been antithetical to what Pollock was trying to achieve.”

However, I don’t want to use this as an excuse for defeatism. Of course we all need to expose ourselves to more art and take a discerning eye to it. At the same time we have to be realistic. Australia is never going to have collections of the sort that you enjoy. And I don’t think that we should. I’d like to see a bit more attention given here to Australian artists. Unfortunately our museums are not about to show any interest in current abstract art, unless perhaps it is plays in to their own self propagating agendas, e.g. the Field. So abstract artists here are going to have to make a red hot go at it themselves, because nothing is going to be handed to them. The structure of the essay uses Brancaster as a model for how to make our art richer, more universal and less alienating, which I think lies in the ambition to be “more abstract”. The suggestion, as I made before, is that if the past has anything to teach us about Blue Poles, why can’t the present? It just takes a bit of confidence, because it risks coming across as self-absorbed.

LikeLike

Just to follow up on Alan’s comments about the word “content”, I knew that using it would be controversial, but I decided not to worry about it, because the essay couldn’t accommodate my pontifications on what the word might actually ‘mean’.

I would have thought though, that an attitude to content where it is thought of as being “put in”, is precisely what leads to painters like Sidney Nolan inserting little bushrangers into a painting that doesn’t need it. So too, the landscape fallback in Jo Davenport. “Putting in” content is what leads to “cultural signifiers”. I’m for the discovery of content, and for myself, I think this will probably only come about in moments of inspired painting anyway.

I have no idea how the other artists in ‘Heavy’ think about or define what goes into their work. But it wouldn’t surprise me if starting to think of that ‘stuff’ as content, may result in a more coherent and clear demonstration of that information, because the word ‘content’ itself imbues those decisions and that visual material with a sense of consequential purpose, rather than it being just frivolous meandering or “filler”.

LikeLike

Harry – I would be interested to know what you and the younger generation think of Fred Williams nowadays. I went to see him in 1972 when I was there (VAB); and he impressed me at the time as having an ‘Australian-ness’ that was not kow- towing to ‘history’.I much preferred him to Nolan.

Also can you tell me more about the Ron Swann ‘incident’ ?

LikeLike

Hi Tim.

I prefer Williams to Nolan as well, but I can’t say I’m a huge fan of his work. I often think there is going to be more to the paintings than there actually is. The most recent memories I have are of very flat “backdrops” interspersed with little flicks and dabs of paint, often resembling leaves or twigs that sit proud of and completely adrift from the coloured ground. They very much look as though he was painting to a plan, at least in those works.

Williams is adored by older generations, but I know painters my age who really go for his work. I used to like it a lot too, but it feels like a long time since his major show at the Ian Potter. That show may have cemented his stature in the minds of my generation. I’ve drifted away from his work since then, and I can recall trying too hard to like it at the time. As I’ve said, I think that the drive towards ‘Australian-ness’ is noble enough, but it is fraught with difficulty. Williams’ work is not objectionable as Nolan’s can be, but it can be relatively bland at times, or just too repetitive.

—————————————————–

The Ron Swann controversy concerned his public sculpture “Vault”, which was commissioned by the Melbourne City council after winning 1st prize in a competition in 1978. It is a large minimalist abstract sculpture painted yellow, and it is currently located outside the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art in Melbourne’s Southbank. It was originally situated in the city square and drew rabid condemnation form councillors and the press. At the time it was untitled, and attracted the derogatory and racist nick name “The Yellow Peril”, which many people still know it by today.

In 1980, the announcement to have it removed and relocated spurred public protests in the City square. My father tells me that the rally was huge and attracted artists from a wide range of persuasions. The problem with these incidents is that they completely cloud our ability to judge the work on its own merits. Australia has a lot of scar tissue. Blue Poles is intertwined with the fate of the Whitlam government, and the damage done by its dismissal in 1975. Vault is similarly associated with debate that is basically about whether or not you think something ‘abstract’ is art. You end up having to defend it on the grounds of cultural significance, even if you think the work itself is lacklustre. I think we should be at a stage where we are grown up enough to simultaneously accept the significance of these events, and be able to look at the works themselves with some perspective. They hold such dominating positions in the cultural landscape because there is much less of a pool for them to be swallowed up by. This isn’t a result of a lack of artists, but a lack of opportunities for them.

LikeLike

Having said that about Williams, maybe it is his ‘Australian-ness’ I’m reacting against, in favour of an inherited European tradition. With that in mind, I’d be interested to see a wide range of his work again. I’ll trust my gut instinct on it for now though.

LikeLike

Thanks Harry.

Not having seen any more Wiliams’ since, I cannot say how he may have developed. I do recall thinking that a lot of his work was a little on the repetitive side as you say:: Bush, Bush and more Bush .But then so was Hitchens.

I tend to empathise with your reaction against ‘ness’; it is probably more constructive to simply go where your feeling takes you rather than worry about cultural belonging.

Good to know that Ron caused a stir. Sculpture has this amazing facility to get people really angry and wiorked up..Good on yer Ron.

LikeLiked by 1 person

‘Blue Poles’ is a far better painting than it looks in reproduction. In photographs the ‘poles’ look like panic interventions, devices to ward off failure, but when the actual work was exhibited in the Royal Academy in 2016 it was probably the most successful painting in the show. It can be best seen in relation to other works by Pollock, like the cut outs and ‘Out of the Web’, where two interlocking fields are in play. Instead of part of the canvas being physically removed to allow another to show through, as in those examples, the presence of a second coextensive field is established by the stable structure provided by the strategically placed roughly linear elements. Interpreted thus the elements in the title are not scaffolding but poles as those in a magnetic field, dividing the events in the painting into two implied superimposed planes.

Greenberg may have been harsh on ‘Blue Poles’ because, as in the cut outs, it goes against the explanations he had developed over the years about Pollock’s practice. For an unflattering account of Greenberg’s relationship to Pollock at this time look at Caroline A Jones’ ‘Eyesight Alone’, well pp 298-300, at least.

LikeLike

https://www.ngv.vic.gov.au/exhibition/the-field-revisited/

LikeLike

Not sure whether most successful work in the show, but I was certainly impressed by Blue Poles at the RA.

LikeLike

“The pressure of the historical moment” is of course a phrase of Matisse’s, when he was saying that the artist, if he is any good, is not free to do anything he wants. He should, as T S Eliot also said, be aware of the momentum of pressure exerted by the best of the art that precedes him, and in Matisse’s development the pressure was intense, not only from Cezanne, Gauguin and the others, but from the younger Picasso especially.

This scenario held good up until the 1960s, when it was undermined by the climate surrounding the Leo Castelli gallery’s discovery of how to manipulate the nouveau-riche taste, or tastelessness of the big collectors and the pseudo- sophisticates of the N.Y. Intelligentia. Rauchenberg’s erasing of a De Kooning drawing, and his “putting in” stuffed birds, car tyres and mattresses in his “artschool cubism”. — Jasper Johns’ casting his toothbrushes in bronze, and all the rest of the Neo Duchampian paraphernalia, Warhol and Lichtenstein’s variants on found object imagery etc etc…. The Greenberg circle, and especially Fried and Darby Bannard, whose writings are still well worth consulting, kept things going into the seventies, but as Caroline Jones’s book relates, their world view was swamped by a tide of hyper intellectualism, anti-form bullshit, aesthetic laissez faire relativism , and much else. And then came so-called “conceptual art”. Walter Benjamin, Susan Sontag (later to retract), and Rosalind Krauss replaced Greenberg as the gurus of choice.

The momentum deflated like a burst balloon and the released air is still all around us. See for instance the clamour of silliness being generated about the British Museum’s new exhibition Rodin and the Parthenon sculptures. When critical insight is so threadbare in the art world, we are indeed working in a vacuum.

I agree with Harry and Robin that there is now no pressure to speak of, unless one engenders it oneself, but I would maintain that the only way to do that is to project oneself imaginatively into these moments of the past and try to experience what genuine pressure is, and to maintain the high demands, critical and self critical which we all experienced back then. Otherwise all one will do is to recapitulate on the side issues, highways and byways, repeating false trails and adumbrations. Which is why I have been sounding alarm bells about all this density and complexity as the only way out.

The issues for sculpture are quite different from those of painting. They are in a different historical situation, and it is folly to elide the one to the other, as regards complexity, putting in content, or anything else.

Which is why the argument about Blue Poles is still prescient. I see that dear old David Sweet has got it wrong again. And “clogged up over- complication” from Robin? One has to smile.☺️😜

LikeLike

I can agree with some of this Alan.

Here is a quote from you that I really like; it has been very helpful:

“A form of free association has already been set in motion diverting whatever conscious aims we may have had, unless of course you are working by rote. In other words ‘conception’ is moved towards by jostling, adjusting the material, just as it is in poetry, and in music too. Painting is a movement towards something-not an attempt to recapture something.”

LikeLike

PS. It’s that “body and mind” issue again. I’d say that in Lucifer, One and Autumn Rhythm, Pollock was visited with a period of perfect balance, where nothing is over determined, forced or cerebrally compulsive. He was seldom able to recreate the conditions for a further visitation henceforth, although there are some near misses, such as Ocean Greyness and Convergence 1954? . But certainly not Blue Poles for the reasons I and others have given (I don’t know what the others have said). There is a lesson for us all in that. Trying too hard, overthinking it, all the cliches, are still valid in daily operation in the studio. Hard won victories? Who needs them. As Cezanne said — “ if I nterpret too much — if I come in one day with thoughts that are foreign to the day before, then everything is lost” (paraphrasing) allegedly.

LikeLike

So pleased to read that you are no longer in a “Blue Funk” and can still smile, even if its out of your derrière. Yes, even I think some things are clogged and over-complicated, but it’s usually healthier than pared-back simplistic minimalism, as in the case of the Pollock.

Well, you certainly made “The Cringe” with earlier comments like “I did not write these for my own benefit, but for yours, if you did but know it. I didn’t need reminding. You did.” Jesus, Alan, where do you get that shit from?

Still, now we’re all happy again and emojoing… And even David’s back… One big happy Abcrit family.

As for pressure of the historical moment, well, you know what I’m going to say now, don’t you…? I know of no situation or construct that has applied pressure quite like Brancaster does and continues to do. Throughout the whole working year. Brilliant.

Though of course it’s not historical. More like futuristic.

So that’s me sorted… you can carry on imaginatively projecting backwards and we’ll imaginatively project forwards – and ne’re the twain shall meet, eh!

LikeLike

“…their world view was swamped by a tide of hyper intellectualism, anti-form bullshit, aesthetic laissez faire relativism , and much else. And then came so-called “conceptual art”. Walter Benjamin, Susan Sontag (later to retract), and Rosalind Krauss replaced Greenberg as the gurus of choice.”

And behind all of that was the corrosive influence of a few completely insignificant intellectual fashionistas from Paris whose vastly inflated reputations somehow enabled their mystifying bullshit to trickle down, inundate and ultimately drown American intellectual life, a sad state of affairs from which we have still not managed to recover.

LikeLike

Speaking of history, which seems to be what we are doing a bit too much of, Bill Tucker opened a show at Pangolin London last night (http://www.pangolinlondon.com/exhibitions/william-tucker-ra-objectfigure-figureobject) comprised of some of his big new lumpy “things” (for “things” they are, according to Sam’s catalogue essay) and reprises of some sixties works immaculately remade only last year (these are to be distinguished from the new “things” because these old things are “objects”, which are apparently different from “things” – who knew?). We also had David Annesley remaking his old sixties sculptures in a new show at Waddington’s a few weeks ago, as reviewed by Sam on this site.

A lot has been said about Caro hereabouts, some of it critical, and quite a lot of that by me, but one thing I will say in his favour – he always moved forwards and never looked back. The same could also be said for Tucker’s contemporary, Tim Scott, if not more so, because with Tim you also get a sense of an imperative to make sculpture in some manner “better”, to progress it, not just to make more of it that is merely different.

There is a bit of a spate of sixties revivalism at the moment, as per “The Field” in Oz and Sam’s “Kaleidoscope” over here. I noticed Carl on Twitter saying American culture was all downhill after the high-point of the mid-sixties.

I’m not a believer. The very best of the Bill Tuckers in last night’s show was a “Cat’s Cradle” sculpture, an open, spatial framework of thin steel rods, painted in metallic gold paint (http://www.pangolinlondon.com/works/cats-cradle-iv/3349). Basically the content of this sculpture is the diagonal strut that rests upon the support in a semi-physical way, almost a gesture. Back in the day, that would have seemed brave, sensitive, radical and excitingly pared back. Now it just looks ever so, ever so slight – the smallest of sculptural content imaginable for a spatial sculpture to get by on.

Even if Carl is right, there is no going back, nor can we stand still. Surely that is just as true for painting as it is for sculpture.

LikeLike

ironic for you Robin to joke about personal definitions of well-worn words!

LikeLike

my catalogue essay is available here

Click to access tucker%20catalogue%20-%20email.pdf

LikeLike

A trifle sarcastic, perhaps, but always happy to discuss, should you feel inclined.

LikeLike

Correction. It is incorrect to say that Convergence 1952 is a near miss. Although I have never seen it in the flesh, there is a good installation shot at a Jewish Museum show of the A.Es, some years ago, in which it is paired on adjacent walls with De Kooning’s Gotham News. Well worth a look.

LikeLike

click on this link to see the photo. They both look pretty good to me.

LikeLike

Carl and Alan – I, naturally, agree with both your comments. The problem is, what are we going to do about it ? We are not going to eliminate Duchampism. or change the minds of the myriad ‘Conceptualist’ curators around the world.whose careers would be in jeopardy.as a result.

Thanks for the compliment Robin – I DO firmly believe in Caro’s “onward of sculpture”. He once said to me that he was not interested in someone writing a biography of him because he looked to the future not the past.That says all about his attitude.

So, folliwing that example, what now for painting and sculpture? At least on Abcrit there is some awareness..

LikeLike

Check out Amaranth Ehrenhalt, surviving abstract expressionist in New York of the 1950’s.

LikeLike

Here’s lots more Oz abstraction at the Charles Nodrum Gallery, Melbourne, related to the “Field” show:

http://www.charlesnodrumgallery.com.au/exhibitions/abstraction-17-a-field-of-interest-c-1968/

There is even a John Peart in it, along with lots of other lovelies from the sixties.

This is from the catalogue on a painting by Richard Dunn:

“This painting’s long horizontality creates for a viewer changing spatial relationships, seeking to establish a physical and kinaesthetic connection between a viewer and the work.In this sense it is a component of an installation – composed of the painting, the viewer and the room.”

What do you think of that, Carl?

LikeLike

That comment on the Dunn painting (not sure which one, and I haven’t see it in any case) strikes me as an example of art critical writing that looks attractive at first glance but when you think it over, it tends not to mean anything. The yellow Dunn painting looks sort of like certain pictures by Noland, and it would be a mistake to describe the relationship between painting and viewer as “physical” (never mind “kinaesthetic”). “In a sense” any picture is “a component of an installation” and “part of an environment”, but that sense is completely trivial and beside the point in the experience of successful art.

LikeLike

Carl – I think it is known as gobbledigook, and is the mainstay of ‘art’ writing

LikeLike

I might be coming back to this a bit late, but I wanted to say that I like Tim’s line of questioning, which concerns two concurrent issues, namely the ‘where to’ for abstract painting and sculpture, as well as the broader art culture itself. I’d like to think that what is good for the goose is good for the gander, and it would seem that all we can do is address the things within our own control, that being the work itself. But if we do turn our sights towards the assailment of culture at large, I would stress that what needs to be banished from the mind is any aspiration towards becoming the establishment. It is the whole situation that allows for the existence of an establishment at all that needs to be re-imagined.

In Terry Smith’s 2017 follow up to his Provincialism Problem he writes,

‘In the end, the responsibility of each individual artist, critic, or curator—all of us “more or less subject to the pernicious destructive-ness of provincialism”—is to refuse to instantiate this system in the ways we go about our work. Critics should refrain from describing the development of artists’ work as if it possessed a “systematic, homogenised immutability”; art lovers should desist from retreating to “instinctual devotion to an amorphous metaphysical entity ‘Art’”; and curators should cease organising international traveling shows that imply “a specious certainty of purpose and a misleading coherence as a range of cultural products.” Artists should not allow their works to be described, understood, or exhibited in these ways. For them, trans- forming art itself remained as the most viable—in fact, only possible— option.’

This sort of critique of the institution is not to be confused with ‘Institutional Critique’, or as a championing of conceptual or performative practices that are that way inclined, because all those things have been completely institutionalised, which assumes that they ever weren’t, or did not aspire to be.

The problem with a lot of discourse that takes aim at the institution and the power structures of art, is that it can lose sight of the very reasons we get involved in art in the first place, and that is for encounters with great works of art. That is why I also thought this passage from Terry Smith is insightful, written for Quadrant in 1971 as a response to Patrick McCaughey’s “Notes on the Centre: New York”. Smith writes,

“Mr. McCaughey’s second major point is also open to considerable doubt. He writes of his ‘revelation’ on a first visit to New York of ‘just how good the old masters really are’. Having had a similar experience in Italy, London and Paris recently, I can agree entirely with him that ‘nothing alters one’s relationship to recent art more than this experience.’ But our responses seem to have been entirely contrary in character. My responses are presented elsewhere in some detail, but in sum the staggeringly high quality of great art and of the achievement of the recent masters made me highly conscious of the pressing necessity to change art radically towards something now unknown, if art is to survive.”

McCaughey was one of the key curators of the Field exhibition in 1968. Smith accused him of suffering from an “updated version of the cultural cringe”, although Smith also played a key part in championing the shift in Australia towards colour painting, seeing it as a great opportunity to put Australia into real time. Ultimately, Smith came to see the colour field endeavour as a failure, because all it did in Australia was manufacture an “avant-garde situation”, or “adopting an attitude” as Greenberg put it, whilst the only true avant-garde developments were happening in the cultural centre, New York. Having now seen The Field Revisited at the NGV, I agree. There is very little about that work that is intrinsically avant-garde. A few oddities, but on the whole, a very self-conscious kind of experience. One of the problems is that whilst this approach to painting in New York was in many ways a response to Abstract Expressionism, in Australia it was seen as necessary to dislodge the Antipodeans such as Nolan, Boyd and Williams. Smith quotes his colleague Mel Ramsden, saying “In what ways is a traveling exhibition of contemporary American art useful or destructive? From where does the information come for an Earthwork to make sense in Australia? Can we presuppose that the viewer of a work by Donald Judd in Paris gets the same information as a viewer in New York? Why do European collectors prefer Art & Language texts in English over translated versions? Why is it that the political concerns of many South American artists have the effect of relegating them to minor status in

New York?”

I think the effect of The Field in Australia has been to forever entrench Minimalist abstract practices as simultaneously being part of a ‘Progressive Establishment’, hence the analogy I used of the Australian Labor Party. It forms the dominant understanding of what it means to be an abstract artist in this country.

For me, something like Brancaster does not pose the same sort of provincialist problems that colour field painting did. That is because it is a marginalised activity, enjoying nothing like the sort of mainstream attention given to previous moments in abstract art, and it prospers as a result of this. Smith wrote of the Australian colour painters that through “their subscription to his (Greenberg’s) formalism as their theory of art (something I had shared in my first attempts at criticism) had limited their ability to resist their work turning into stylisations of itself.”

I think that a forum committed to artistic change rather than consolidation will resist assimilation and institutionalisation by its very nature. That was one of the motivations behind the essay.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Harry thanks for your thoughts on ‘the Cringe”. I do think it’s the reason why so many Australians move overseas, to submerse themselves in their chosen fields. Many do it and as Mr Greenwood says it’s not worth getting hung up on; you seem to be doing fine by making the connection with Brancaster and getting yourself out and about.

I’ve a huge respect for the folk at Brancaster and have enjoyed the banter and thinking for a while now, which led me to go see John Bunkers collages last fall whist visiting London, being able to engage in a long char with John about his work, and also having the pleasure of seeing Alan Gouk’s Paintings at Felix and Spear (though disappointingly not the opportunity to meet Alan). Robin Greenwood also kindly sent me a recent catalogue for an exhibition he was having and I only wish I could have seen the work in person, as I agree with all who’ve touched on this, it’s vital to see the work in person and over time again and again.