HARDPAINTINGX2 at Phoenix Art Space, Brighton

An exhibition in two parts featuring work by:

Part 1: Richard Bell, Katrina Blannin, John Carter, Catherine Ferguson, Della Gooden, Richard Graville, Morrissey & Hancock, Tess Jaray, Jo McGonigal, Lars Wolter and Jessie Yates

Part 2: Rana Begum, Ian Boutell, Philip Cole, Biggs & Collings, Deb Covell, Stig Evans, Jane Harris, Mali Morris, Jost Münster, Patrick O’Donnell, Carol Robertson and Daniel Sturgis

Hardpainting as a concept appears to be difficult to pin down. The best advice would be to engage in primary research and visit the exhibitions and see for yourself. Or, if that is not an option, make a note of the exhibitor’s names and search out their works at other venues. For secondary research, trawl through your catalogues and bookshelves and visit the artists’ websites. As you form some notion of what Hardpainting is, there’s one important proviso: exclude the figurative. And a recommendation: be a little speculative and maintain a spirit of deliberate inexactitude. Also, pluralism is good (it’s certainly contemporary), for Hardpainting is not to be placed into a theoretical straight jacket. At least not yet.

If you have been able to see the exhibitions at Phoenix Art Space (the first in 2018 and reviewed on AbCrit; and this one split into two parts) you would have experienced the typical white cube aesthetic. The curators have risked nothing to present the works in the most contemporaneous way. Predictably, the walls were painted white, and a desire to give plenty of space for works to be displayed alone or in twos or threes has ultimately required splitting the duration of the HARDPAINTINGX2 show into two periods of time (about three weeks each). Nothing has been labelled, although a plan and list is available, and there is no provision of seating. The visitor is free to roam in a generous, warm and well-lit space. The only distraction was the persistent hum of traffic outside: but this contrasted with and emphasised the restful quietude of the presence of the artworks in the gallery. Hardpaintings are unlikely to get the heart racing, but potential visual bliss is a highly likely outcome for an engaged viewer.

HPX2 (as well as the 2018 exhibition) certainly avoided ‘hard-definition’ but the project, so far, has accepted contrast and even contradiction as one practitioner’s labours might be compared to another’s. Take for example Morrissey & Hancock and Jessie Yates from Part 1 or Mali Morris and Daniel Sturgis from Part 2. Here we find mathematical and systems practice (M&H) and organic colour collage (Yates) on adjacent walls; or impeccably placed, lean and supple but painterly colour/shape and elegantly composed quasi-geometric configurations (Morris), contrasting with almost hard edge visual conundrum and visually unsettling scenarios (Sturgis), respectively. Or less contradictorily, the temporary and site-specific installations of Della Gooden that relate at least in spirit to the more object-oriented but stretcher and canvas rejecting pieces from Deb Covell – joined perhaps by the dark and humorous theatricality of Jo McGonigal’s ‘Kiss, Kiss, Bang, Bang’.

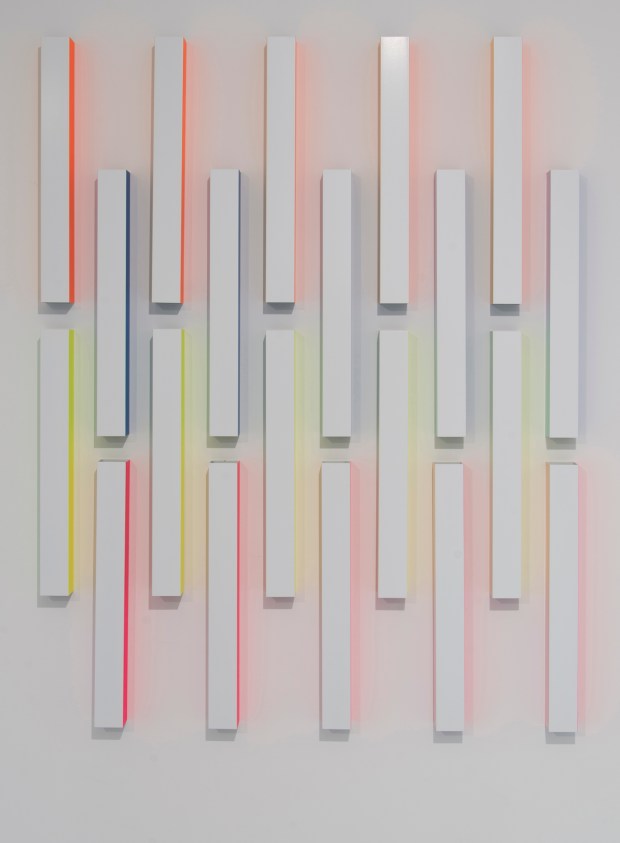

Other brothers-in-arms might place Lars Wolter and Patrick O’Donnell into the well defined visual and ‘new to the world’ architectonic artefact, constructivist camp, alongside Philip Cole’s ultra smooth colour impregnated resin compositions that suggest a near sculptural, like-minded appropriation of painting with Wolter – who has painted the glossiest surfaces known to humanity. Rana Begum and Katrina Blannin also join the surface/shape contingent with their immaculately fashioned compositions. Begum’s ‘No.948’ and ‘No.917’ veer dangerously close to sculpture, but being wall-mounted keeps these precise and neo-post-impressionistic constructions within the conventions of painting. Blannin programmatically refuses to play with expression and facilitates the handling and arrangement of simple colour shapes to give agency to the planar environments of the four canvases that make up ‘Sequence #2/4 (P)’.

The flat but slightly canvas weave inflected surfaces (and almost indistinct brushwork) of Tess Jaray’s ‘One Hundred Years [Purple]’ set the tone at the start of HPX2 Part 1, as did Carol Robertson’s ‘Colour Map – Yellow’ for HPX2 Part 2. From Jaray’s two large canvases the central spines, with intersecting and totemic linear meeting edges, find an echo in Jane Harris’s painterly but controlled rococo minimalism (to steal a term from Barry Schwabsky’s essay ‘Artificial Life Forms’). Harris has a wall to herself with three canvases. In each the medium (paint) is almost sculptural on the surface. I say almost because she is not dealing with three-dimensional form but with a manipulated surface, approaching relief, as image. The colour, combined or constituted as materiality (texture, shape, pattern), is ornato – “additional to clarity and correctness” (see Michael Baxandall’s essential ‘Painting and Experience in Fifteenth Century Italy’).

Tess Jaray, ‘One Hundred Years [Green]’, 2017 and ‘One Hundred Years [Purple]’, 2017, each 151x142cm

Carol Robertson’s colour drenched configurations might also be associated a little loosely with Richard Bell’s geometric miniature colourfield-geometric configurations. These in turn intensify and define the flat forms that appear in the misty, sfumato atmospheres of Stig Evans’ canvases. Fascinatingly keeping the art historical references active, Catherine Ferguson’s paintings, including ‘Cieco’ and ‘L’arresto del Tempo’, maintain links with the intricacies of Caravaggio’s compositions and Baroque painting. From her APT Gallery talk in 2017 she stated that: “A painting has to start somewhere. To even think of making a painting is to be already within a certain tradition.” Such an admission hints at postmodern appropriation, but her results are far from ironic as her gentle paint handling and almost minimalist configuration of disparate shapes cajoles a fresh feeling of surface, light and colour.

Bringing tradition closer in chronological time, Jost Münster and John Carter are constructivists of sorts. Münster’s pair of works pushes the broad definition of Hardpainting into collage territory (as did Yates and Boutell) for its embracement of non-painting media (reminding the viewer of John Bunker’s impressive work from the original HP show). Into more optical territory, Richard Graville and Ian Boutell both have a thing about stripes which Gooden describes in one of her four essays in the catalogue as a “…sensual and material engagement with Painting… they embrace the ‘psycho-physical’ realm”. As briefly mentioned earlier, Daniel Sturgis’ open and expansive imagery also contains a degree of visual aberration in works that avoid deadpan hard edge (employing masking tape) abstraction by being so carefully painted and simply composed. The work embraces contradiction by being precise and inexact, inviting slow looking.

Daniel Sturgis, ‘Not Fixed III’, 30x35cm; ‘Not Fixed I’, 76.3×137.2cm; ‘Not Fixed II’ 30x35cm, all 2019

Another way into Hardpainting as an approach to making the cultural product called Painting might be to imagine that the first quotation in the catalogue from Matthew Collings (who is included in the show with ‘Night’, a simple and complex Biggs & Collings canvas that invited hours of contemplation) is pinned up in each of the contributor’s studios: “The more materialist painting is, the better.” This emphasise on the materiality of form and concrete image over external, associative concerns (however laudable or fashionable in more figurative realms) allows for full attention to the making of the pure, unadulterated abstract, rather than the associative, spiritual, value-laden abstract. Though what constitutes “better” might invite any number of definitions and personal preferences.

Lars Wolter, ‘Cut-Off [Altrosa]; ‘Cut-Off [Enzianblau]’; and ‘Cut-Off [Goldgelb]’, all 2019, each 92×62.5×6.5cm

Where this mission to limit or clearly define the practice of painting was, was not discussed further and the “fugitive” was also left in some abeyance, though approximated at times in the subsequent talks by the other speakers. For example, Emma Biggs touched upon this latter point by saying that the Biggs/Collings project was “curiously hermetic” in their “sewn up collaboration” and Matthew Collings added that the works “began with nothing…no system”, but would “arrive at a mathematical logic”. He also revealed that the collaborative work was not “an expression of individual subjectivity”. Philip Cole spoke later and talked positively about labour, process and learning. He emphasised “a love of material” and that one must “honour the material” in a “world that is collapsing”. From these comments on choice, action and engagement, including reverence for materials, the fugitive disposition might partly be characterised by a willingness to take every opportunity to be highly disciplined and equally focussed on input and output as necessary. In this sense, the products of the painter integrated with the temperament of the maker and characteristics of the materials. Referring to the show as a whole, Collings added that all of the works had “an attitude and were playful”. Hence, the works would be as individual as the makers themselves, which has resulted in a fascinating assortment of outcomes.

It might be that every painter selected limits his/her practice in some way and that the chosen works (56 pieces from 23 artists if we count Morrissey & Hancock and Biggs & Collings as one each) demonstrate this within broad territory. As we all know, definitions of painting practice, from the cave wall and fresco, to easel painting and performative works on the studio floor, and latterly to the ‘expanded field’ phenomenon, will find placement in various ethnological, devotional, private, social and institutional contexts. The postmodern condition may well be liquid (or confused), settling down for a while in various corners of the marketplace or cultural institution, and providing a rich feeding ground for a burgeoning academic research culture that places ‘art’ into the anthropological and/or social purpose/political realms. Consequently, hardpainting artefacts, on the evidence of all three exhibitions, seem generally to appear from the hand of the maker; from the studio environment; and offered as honestly and unpretentiously celebrating production skills and deep engagement with materials. Bringing these various projects to fruition is ultimately characterised by a compelling visuality that is, in essence, abstract.

It is crucial to acknowledge that the catalogue, with obligatory quotations, introduces a latent Materialist identification and argument for so-called Hardpainting. But the evidence on the walls has been so broad and disparate that the differing interests and ‘tastes’ of the selectors soften hard intention. How appropriate then that the curators, Della Gooden plus Phoenix Art Space artists Philip Cole, Patrick O’Donnell, Stig Evans and Ian Boutell, were, perhaps, running away from defining Hardpainting. But that is a little too harsh of me, for the project that Hardpainting is becoming might be a purposely transitory and open way of presenting a broad body of works from a small selection of contemporary painters who not only eschew the depictive, figurative and overtly expressive or reference any narrative beyond the specific artworks. Notionally, they all embrace a Protestant work ethic for making what might loosely be termed ‘abstract art’ with certain materials (most especially but not always exclusively paint) and for forefronting the processes of using said materials and for exploring and celebrating the essentially reductive materiality of painting. Furthermore, oblique subject matter (or matter as subject) is given preference over historical (which includes the present) or spiritual associations – which are not purely religious but might include notions of temperament, personality, the sublime or reverence and association with/for Nature.

Ian Boutell, ‘Slipslideshift II’, 2019, 49x49cm; ‘Semper’, 2020, 100x100cm; ‘Slipslideshift’, 2019, 49x49cm

I mention the ‘spiritual’ (such a dangerously loaded term) with reference to the material and visual aesthetic qualities to be found in abundance in Hardpainting artworks. This might be from the choice and use of materials (e.g. Boutell’s Perspex and Cole’s polyester resin), the selection and combination of colours (e.g. Bell and Morris), paint handling (e.g. Robertson and Harris) and internal composition (e.g. Ferguson and Biggs & Collings) to placement in the gallery space (e.g. Gooden and Covell). Every exhibitor is an expert of sorts, but none are mere technicians. Every work is more than the sum of its parts. These qualities, conditions and characteristics always possess a certain magical potential. Some works engage the viewer more than others, for sure. But I would argue that there is always room for the inexplicable and the non-verbal, secular consummation of the abstract in artworks. So it just might be worth opening up to the indefinable qualities that permeate materialist, Hardpainting.

The second quotation from the catalogue foreword puts the work into a potent philosophical and academic context: “Aware of the intractability of matter, materialist thought promotes a respect for the otherness and integrity of the world, in contrast to the postmodern narcissism that sees nothing but reflections of human culture wherever it looks.” Terry Eagleton (from ‘Materialism’, 2006, Yale)

A rational, materialist non-dogmatic world-view may well appeal to pure abstract painters (by which I mean the work is a system in itself and not encumbered with notions of referencing external subject matter, unless by chance). But would it be blasphemous to the School of Materialism (if there is one) to succumb to the emotional effects of the material and visual? Or even to say that Hardpainting is a misnomer? Undoubtedly the Hardpainting project has more ground to explore, not only with additional painters, but also in other venues. Pertinently, the exploration must be through the works of artists (not only painters), with commentary providing guidance, clarification and exegesis rather than dictatorial and doctrinaire restraint.

Notes:

It is worth noting that HARDPAINTINGX2 attracted essential funding support from the Lottery/Arts Council England and from crowd funding by the five curators.

Also, as this review is quite generalised I recommend that you read the reviews that apply to each of the three manifestations of Hardpainting from the following sources:

Hardpainting (2018)

https://abcrit.org/2018/01/20/93-geoff-hands-writes-on-h_a_r_d_p_a_i_n_t_i_n_g-at-pheonix-brighton/

HardpaintingX2 Part 1

https://fineartruminations.com/2020/01/30/hardpaintingx2-part-1/

http://www.saturationpoint.org.uk/Hardpainting%20review.html

HardpaintingX2 Part 2

https://fineartruminations.com/2020/02/13/hardpaintingx2-part-2/

Other links:

Saturation Point – Della Gooden essay

http://www.saturationpoint.org.uk/Inside%20the%20outside.html

Phoenix Art Space

https://www.phoenixbrighton.org/events/h_a_r_d_p_a_i_n_t_i_n_gx2/

Jane Harris – Barry Schwabsky essay

http://www.janeharris.net/essays/artificiallifeforms

Catherine Ferguson

Bernard G Mills took most of the photos shown here.

Brilliant

LikeLiked by 1 person

why did you think the article was brilliant?

LikeLiked by 1 person