Jasper Johns, “Painting with Two Balls”, 1960, encaustic and collage on canvas with objects (three panels). 165.1 x 137.5 cm. Collection of the artist © Jasper Johns / VAGA, New York / DACS, London 2017. Photo: Jamie Stukenberg © The Wildenstein Plattner Institute, 2017.

Some thoughts on Jasper Johns currently showing at the RA until 10 December 2017

The title of this show is ‘Something Resembling Truth’. These particular words have been hacked away from a longer ponderous statement by the artist and to get the ball of conundrums rolling in that all too familiar cold blooded Johnsian manner – you have to ask – what does that really mean? What ‘truth’ are we talking about here? A truth about painting? A truth about life? Surely all that ‘life’ business is just conjecture? And how do we go about ‘resembling truth’ or life or both? Is not this title just adding to an already monstrous scatter of ‘truisms’ and ever multiplying thick coffee table tomes full of puff? Just as a shaman scatters her bones, does not a twitter-feed sometimes appear a wreck of truisms, a random cast of signs and signals, warnings and affirmations, all back lit on our tablets with a tinge of desperation?

But the real shaman’s signs and emblems would have specific meanings. Interpretations of predicaments and predictions would then be based on such criteria as, where the chosen objects fell when they were thrown, in what combination: upside down, eschewed or perfectly aligned? Even the shadows they then cast could be ripe for interpretation by the initiated and knowing eye. And Johns gives us the continual recasting of reccurring motifs and signs upon the canvas – an apparent randomness of objects and images, some of which we all know and, in our own way, we have internalised. The paintings then seem to take on a sort of weight and seriousness of official insignia almost perfectly designed for the catch-all we call ‘Modern Art’, supplying it with its very own Johnsian coat of arms. Flag, target, crosshatch, skull, paintbrush and lightbulb for instance, in whatever combination is desired.

Jasper Johns, “Painting Bitten by a Man”, 1961, encaustic on canvas. 24.1 x 17.5 cm. The Museum of Modern Art, New York © Jasper Johns / VAGA, New York / DACS, London © 2017. Digital image, The Museum of Modern Art, New York/Scala, Florence.

His works have been hugely influential for how they bear down upon our shared world of signs. These are the signs by which we organise another world, one of exchanges, of communication, of power, of commerce, even the intimate and domestic (all of which the history of painting has its own particular ambivalent relations to). Importantly, this Johnsian insignia is somehow inscribed with a painterly penchant for scarring – and always gives a nod to the abject and the useless, that, I would argue, infer an emotional register rather than the famous dumb ‘neo-dada’ or deadpan one.

Johns taps into a reservoir of pent up emotional dependency upon the signs, symbols and objects we are surrounded by or surround ourselves with. These images and objects are always sullied by, and thus animated by, our own personal attachments to them. We rely upon them to help contain and coordinate our navigations of life experience. This is somehow echoed in Johns’ paintings and objects and their cloying materiality. Johns seems to dredge all this up by the process of painting them or by the process of drowning them in thick encaustic. And just as the victims of Pompeii were petrified in cooling lava, Johns infers a disjointed awkward bodily physicality, either by the overt use of cast body parts or by the leaving of traces of human presence, whether that be the humble hand print or the almost violent teeth marks of Painting Bitten by a Man. Is this obsessive re-painting of signs and objects in different permutations a way of interrogating these images or painterly procedures and styles in the hope they may yield up something else? But what is that ‘something else’?

Forced together in a clunky caricature of a cubist space, this vocabulary of signs act like secret agents carrying out seemingly endless pictorial covert operations. Cups, forks, numbers letters, skulls, strings and stretchers peek like so much flotsam and jetsam buried in their encaustic camouflage. Johns predicts the choppy, churning currents and riptides created by the tensions between abstraction and representation, in which advanced abstract painting would go on to both sink and swim (think Richter and Polke for example, then Halley, Wool, and now Wade Guyton). But he also throws us back into the Vanitas idiom of still life painting through that deliberately ham fisted cubist lens. In the 17th century’s very own Wealth Porn, conspicuous consumption, declarations of love, intimations of death or dreams of sexual congress were sublimated into a set of symbols arranged in countless permutations to avoid the wrath and tantalise and arouse the Puritan establishment of Northern Europe. At the same time though, Johns seems to return again and again to Braque’s famous trompe-l’œil nail on which the artist’s palette hangs in Violin and Palette from 1909. This breakthrough cubist painting rivals Picasso in its insouciant decontruction of the still life genre. It seems to hold representation, and the will to atomise and abstract it, in some kind of thrilling tension. It seems to me this is the tension that Johns has attempted to assimilate as a guiding principle in his later work.

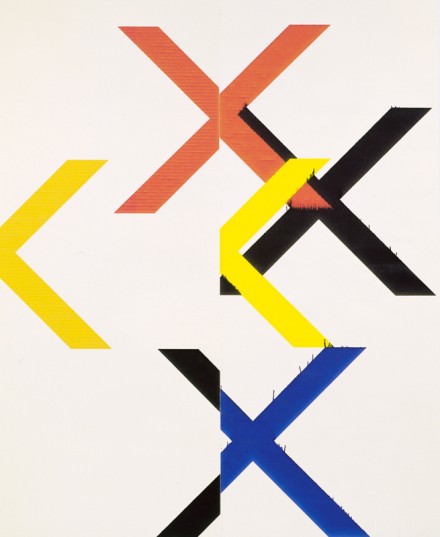

Jasper Johns, “Between the Clock and the Bed”, 1981. oil on canvas. 182.9 x 320.7 cm. Collection of the artist © Jasper Johns / VAGA, New York / DACS, London 2017. Photo: Jamie Stukenberg © The Wildenstein Plattner Institute, 2017.

Johns turns the building blocks of representations into abstract signs and abstract imagery of action and agency into cooled representations of themselves. In ‘Between the ‘Clock and the Bed’ 1983 crosshatchings, famously liberated by Johns from their job of representing anything at all, are now imbued by him with an almost unhinged animation. They listlessly yet relentlessly march up and down its three panel structure, each row of intersecting parts like battalions of matchstick soldiers digging up the picture plane into shallow trenches. Here though, their uniforms are changing colours, their pace seems to increase or decrease as grey moves into yellows into purples into reds and orange only to fall back into greys and cool blues. As we instinctively ‘read’ the painting from left to right, the crosshatchings’ rhythms (akin to the tic toc of the conspicuously absent clock of the title) collapses into the bottom right corner, in jangling criss-crossings of blues, yellows and reds on white. Meanwhile another frozen white partitioned 3-part rectangle of ghost-like crosshatchings hang in suspended animation above the shifting colour sequences in the far right panel. In another kind of painterly attack from the 60’s we see intensely coloured brush marks making their appearance in ‘Painting with Two Balls’. Here, they have been appropriated from Johns’ AbEx predecessors but almost bled dry of any agency (almost but not quite) by the comical split across the painting’s upper half. Those two little balls hold open that gash and the painting’s flimsy facture is made plain for all to see. So much for all that ‘Ballsy’ painting, right? Or there’s the printing of Johns’ own name across various painting’s surfaces at which point, all of a sudden, we might see a sign of a skull as it turns it’s glaring voided eye sockets upon us. Is this Johns’ “truth”? If so, again, what sort of truth is it?

Jasper Johns, “Regrets”, 2013, oil on canvas. 127 x 182.9 cm. Collection of Marguerite Steed Hoffman © Jasper Johns / VAGA, New York / DACS, London; Photo: © Jerry L. Thompson

After so much repetition and reiteration though, even a soaring high camp wit can so easily plummet into the shallow luke warm pool of the just plain twee. In the undoing of signs by painterly means, these emblems easily become reconfigured as slightly stuffed and bloated scarecrows of their former selves. Some might say that Johns is to painting what embalming fluid is the corpse. Those objects and their pigment-loaded waxy doppelgängers skirt around each other, akin to a sort of painterly shadow boxing. The picture plane here though is an arena quite different to the one set up by Harold Rosenberg for the previous generation of American abstract painters. Rosenberg’s idea of painting as ‘action’, of ‘becoming’ through ‘doing’, is returned to us by Johns as an activity of undoings – undoing the myriad signs given us by the modern world or the history of art. His is a picture plane of decoys and double takes, claims and counter claims for and against the heroics and anti heroics of the endeavours of the painter. Johns monumentalises the seemingly trivial and destabilises the hierarchies that we took for granted as the subjects of the artist. Many Pop artists did this but none, at the time, seemed to take this dagger so close to the heart of serious painting. But equally, there is also a tantalising suggestion that painting is a way of rejoining – of stitching back together a hopelessly fragmented self. It’s tantalising because it is denied in Johns’ oeuvre as much as it is asserted, confessed and then all confessions are immediately retracted. Like a Vanitas or a vacant lot or the coveted intimate bourgeois spaces ravished by the cubist insurgency at the start of the 20th century, these paintings are always full of potential but equally places of loss and failure. They are laden with the litter of half hidden histories and their exquisite unravelling too.

Jasper Johns, “Target”, 1961, encaustic and collage on canvas. 167.6 x 167.6 cm. The Art Institute of Chicago © Jasper Johns / VAGA, New York / DACS, London. Photo: © 2017. The Art Institute of Chicago / Art Resource, NY / Scala, Florence.

And what of the unknown pleasures and new fears that our rapidly expanding world of screen-based signs and icons harbour? Well, Johns’ thick painterly alphabet soup of phantasmagorical insignia has been cooling for the last 60 years in the setting sun of the first pop age. This exhibition is wallowing here at the RA, sometimes almost elegantly, in its failure to comfort or convince. Is this ‘something resembling’ our modern experience of ‘truth’? Better cast them bones again, Jasper, in the dying of that light.

I’m astonished and impressed. You make him so much more interesting than he is. Marvellous bit of writing.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Just loving “Johns is to painting what embalming fluid is to a corpse”.

LikeLiked by 1 person

To nick a phrase off Brian Logan in the Guardian: “More arch than a Roman aqueduct.”

LikeLiked by 1 person

In the beginning of my ZF essay I touch on the linguistic turn in philosophy supposedly initiated by Heidegger that overturned the dominance of self-consciousness as the basis of how we understand the world to ground the self in language. Self-consciousness was grounded in perception, the single viewpoint that science used to describe and analyze the world. Just look at art from the Renaissance until the end of the19thc and you will see the power of chiaroscuro and perspective(both perceptual constructs of the eye/mind) as the ground of that self-consciousness, epitomized by the first reproduction of Durer in my essay.Both empowered the viewpoint of the individual to describe the world around them. Clearly Johns is on the other side of that linguistic turn which as Bunker’s essay points out deconstructs and mocks the tradition of perceptually based painting and opens it up to a world of signs and symbols. Unlike Zombie Formalism there still seems to be human being behind the signs and symbols of Johns’s painting albeit a snarky one. Guyton et alia have exited the site of painting.

http://martinmugar.blogspot.com/2013/12/zombie-artthe-lingering-life-of.html

LikeLike

Yes. The linguistic turn – the demonstration of the far reaching influence but also of the inherent limitations of language – could be seen as confirmation of the importance of art in all its forms, with whole aspects of existence – “that whereof one cannot speak” – shown to be inaccessible to the language of science and rationality.

Instead it seems that artists like Johns have hastened to become mere illustrators of language-based ideas.

As long as there are surviving jpegs, titles and a few words of description, works such as “Painting bitten by a man” or “Painting with two balls” could readily be destroyed without any loss to humanity. Their substance is conceptual. There is nothing specific about them as paintings.

LikeLike

Agree! HIs ab-ex quotes in the “Painting with Two Balls” in the end are just bad painting and with generations of artists inspired by Duchamp to undercut the power of representation the slash with the two balls no longer seems all that fresh, intelligent or necessary. I included a photo of him by Yousef Karsh in my latest blog. Johns gets the Karsh treatment and comes across as a deep thinker in the photo, which we now know he is not. http://martinmugar.blogspot.com/2017/10/the-show-goes-on-schnabel-fils-walter.html I like your notion of artists like Johns becoming merely illustrators of language based ideas.The devolution of artists like Kiefer,Winters and Rothenberg from producing somewhat interesting paintings into illustrators did not take long. http://martinmugar.blogspot.com/2013/08/this-somehow-got-deleted-from-my-blog.html

LikeLike