Matisse’s oeuvre can be divided into numerous periods, (and not just for curatorial convenience), too many to list here, but each stylistically distinct from the previous (though not so obviously as with Picasso), and with a different set of priorities both formal and expressive, much more so than might appear to the casual observer.

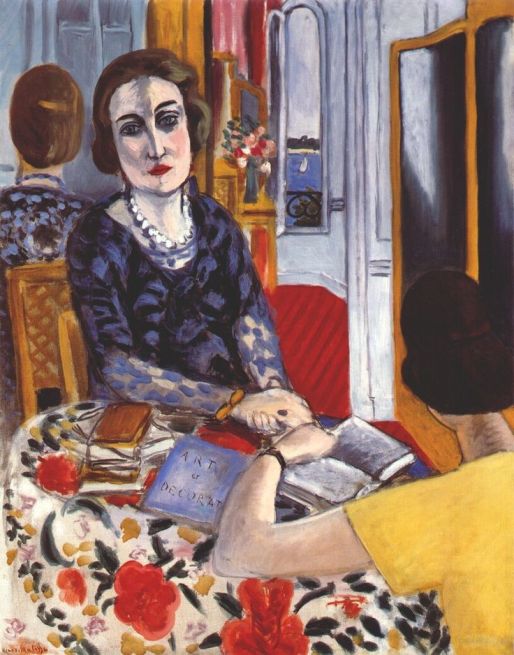

I choose to write about this particular picture, The Baroness Gourgaud, almost certainly a commissioned portrait from the wealthy Baron, partly because it is one of Matisse’s finest portraits, utterly different in character from the great Madame Matisse in Rouge Madras 1907, (Barnes Foundation), or Auguste Pellerin, 1916, or Woman in a Turban, (Laurette) 1917, (Cone Collection, Baltimore), but also because it reveals many of the devices he had learned from Persian and Indian miniatures, by which Matisse ordered his spaces in the more relaxed setting afforded by the early Nice years, after the intensity of his engagement with Picasso’s and Braque’s cubism, to which the Pellerin portrait attests, during the first world war, the so-called “Radical Years”. But Matisse was always “radical” in ways which escaped most commentators then and now, who tend to downgrade the Nice years for reasons which amount to no more than Puritanism and philistinism. Renoir’s sensuality accrues similar opprobrium, quite unjustly.

John Golding writes: ”But basically for him [Matisse] the decorative came to mean an allegiance to the totality of the painted surface and to the overall spiritual and emotional aura that radiated from it… Matisse is one of the very few Western artists who have been able to invest pattern, normally associated with flatness, with spatial properties”. (Matisse and Picasso, Tate Modern 2002). [Braque in the 1930’s is another]. And Matisse himself said: “Persian miniatures… through their accessories… suggest larger spaces, a more truly plastic space. That helped me to go beyond the painting of intimacy”. (Dominique Fourcade ed. Matisse – Ecrits et propos sur l’art. Paris 1972 page 203). The intimacy would return with paintings like that of The Baroness, however.