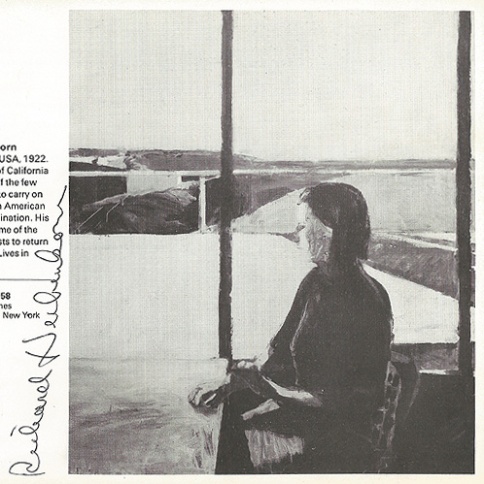

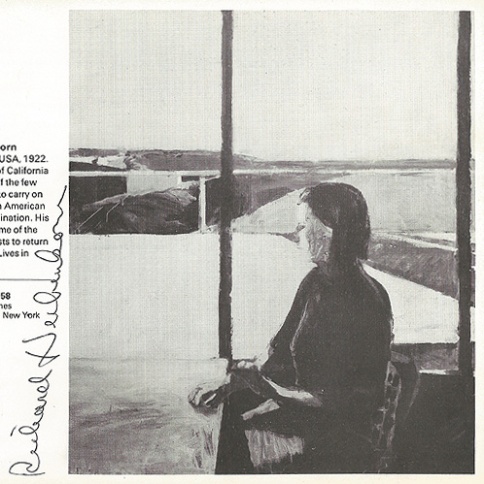

Richard Diebenkorn, “Woman in Profile”, 1958, Oil on canvas, 68” X 59”. Image, with artist’s signature, from Dunn International catalogue, 1963.

Richard Diebenkorn’s Ocean Park series seems to have been initiated as a response to two paintings by Henri Matisse; View of Notre Dame and French Window at Collioure. Both date from 1914 but had never been exhibited before being included in a Matisse retrospective in 1966, organised by the University of California and shown in Los Angeles, Chicago and Boston, but not New York.[i] I want to argue that Diebenkorn recognised something important about these paintings. He saw that they introduced and valorised a particular pictorial economy, characterised by simple means and finite quantities.

Despite the difference in age, the works were similar to a kind of painting then being made in America. The same year Frank Stella’s Irregular Polygons and Barnett Newman’s Stations of the Cross series were also shown. Anyone who saw the three exhibitions would have faced an interesting triangulation; the Matisses, like the light from a new star arriving fifty years after the event, an ambitious late career statement from a major Abstract Expressionist and a set of unconventionally configured canvases from a 30 year old star of the New York art scene.

These coinciding exhibitions arguably constitute an important cultural moment, and one can imagine the impact on a sample viewer of the combined experience. It would be clear that the terms of a new pictorial economy had been constructed, validated and even historically provisioned, by obviously successful, high net worth examples. It would also have offered evidence for the possibilities of abstraction made under the auspices of this economy. What I want to suggest is that it is impossible to fully understand abstraction’s contemporary potential, and past achievements, without recovering this moment and absorbing an appreciation of the associated pictorial economy into our critical apparatus: So there.

(more…)