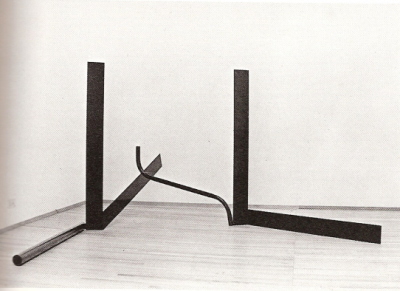

Anthony Caro, “Deep Body Blue”, 1966. Steel painted dark blue, 48 ½ x 101 x 124 inches. Private collection, Harpswell. Courtesy Annely Juda Fine Arts. Photo: John Goldblatt.

Deep Body Blue

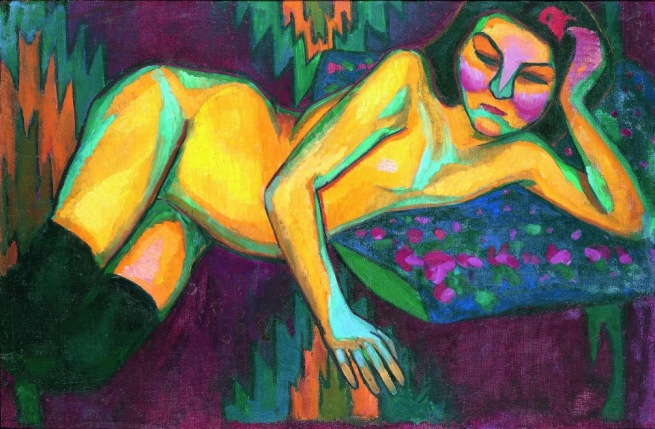

Michael Fried is today one of the most interesting and perceptive art historians in the world. In the 1960s however, Fried was, along with his mentor Clement Greenberg, perhaps the most insightful critic of contemporary art in the United States, and certainly the strongest advocate for what was then known as “modernist” painting and sculpture, as epitomized in the work of Morris Louis, Kenneth Noland, Jules Olitski, Frank Stella and English sculptor Anthony Caro among others.

Fried’s best art-critical writing was done between 1965 and about 1972 as short reviews of exhibits published in Art International and ArtForum[i]. These short descriptive pieces are for the most part limited to careful descriptions of specific works of art, but at the same time seem to achieve the quality of philosophical prose, although Fried did not set out to write philosophy[ii]. I think that this perception has to do both with Fried’s formidable talents as a viewer of art and with the nature of the objects being described. In this article I will try to convey a sense of what it is about those objects that allows or indeed compels an accurate description of them to be read as philosophical prose.

Before we get there however, I want to take notice of the fact that the kind of evaluative art criticism that Fried practiced during 1966-67 (and before him, Clement Greenberg) no longer exists. The world has changed, the art world has changed, and art itself has changed in such a way that the concepts of aesthetic quality and value (and therefore the evaluative judgments that are based on these concepts) are no longer central or even relevant to the kind of art that had replaced the high modernism of the 1960s. It often seems as if the concepts of quality and value no longer matter in our society. I do not purport to explain why that is the case, but simply to register the fact that something has been lost, and its loss represents a significant turn in our cultural history, for better or (far more likely) for worse.[iii]